Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

There’s nothing more nostalgia-inducing than a trip down memory lane with your taste buds. Your long-ago visits to classic restaurant chains with family and friends surely produced many indulgent memories: the mac-and-cheese at Howard Johnson’s, the happy hours at Bennigan’s, the crepes at once-trendy The Magic Pan.

Alas, changing times and tastes of aging boomers have helped spirit away many of those establishments. “Every day boomers are leaving the market” – in other words, passing away, says Alex M. Susskind, professor of Food & Beverage Management at Cornell University’s School of Hotel Administration. “Even if chains can still appeal to that demographic, it is shrinking. I would also argue that boomers’ tastes are changing, and what appealed to them when they were younger, single and/or raising their families is not the same.”

That’s fair warning to today’s crop of popular restaurant chains (and affiliated suppliers and investors), which may soon feel the heat of the shifting tastes and loyalties of Gen X and millennials. “Younger consumers are loath to sit in a restaurant for an hour, unless it is really something special,” Susskind says. “Under the best of circumstances, a meal at Applebee’s or Friday’s takes about an hour.” Younger consumers are “more interested in quality and are willing to pay for it -- eat out less, but better. They are more interested in sustainability, and they love delivery and takeout.”

Consider the changing trends and operational missteps that led to the retreat or outright demise of these 14 classic chains:

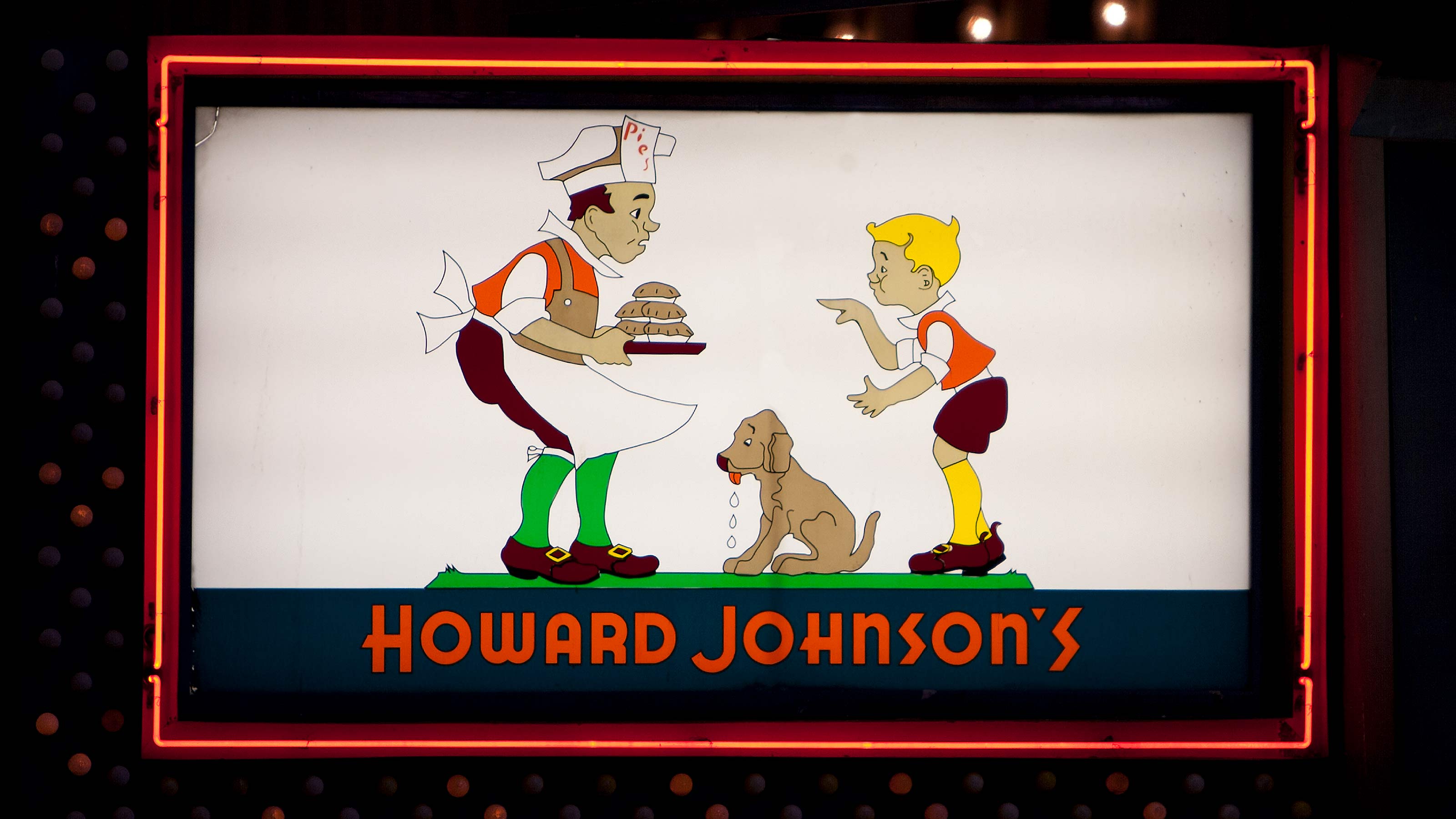

Howard Johnson's

What took the mojo out of HoJo? In the 1950s and ‘60s, Howard Johnson’s restaurants were a real roadside attraction for baby-boomer kids being carted around in the car by their Greatest Generation parents.

Howard Johnson’s was a pioneer of the nationwide roadside restaurant, replicating from coast-to-coast everything from its signature orange roof, cupola, the Simple Simon and the Pieman plaques, and its limited-menu food items. Howard Johnson’s presaged the success of McDonald’s doing the same thing. At its zenith, Howard Johnson’s operated more than 1,000 restaurants, including the Ground Round brand.

But failing to update its menu -- centered around fried clams, chicken, hot dogs and ice cream -- its infrastructure and marketing, along with increased competition from the likes of Friendly’s, Applebee’s and Chili’s, sealed the fate of the Howard Johnson’s restaurant chain. The last one closed in 2017, in Lake George, N.Y. (Note: the Howard Johnson hotel chain is still operating.)

Says Susskind, “They relied on a road travel-based crowd that changed or disappeared when airline travel became more affordable.”

Arthur Treacher's Fish & Chips

Arthur Treacher, a real-life English character actor (you may know him as the butler Jeeves in some Shirley Temple movies), was the spokesperson and nameplate for Arthur Treacher’s Fish & Chips, but wasn’t the owner of the chain that at its peak had 826 restaurants in the U.S. (Trivia Night factoid: Dave Thomas, the founder of the Wendy’s restaurant chain, helped get Arthur Treacher’s rolling in Columbus, Ohio, in 1969, before launching his Wendy’s juggernaut out of the same city.)

Arthur Treacher’s recipe, and menu, was simple: Focus on the British staple of fried fish with a side of oversized French fries (chips), and serve it up in large quantities. The founders acquired the recipe from Malin’s of London, which originated the idea of serving customers on-the-go with deep-fried fish and chips, soaking in malt vinegar – in the 1860s.

The downfall of Arthur Treacher’s began in the 1970s, when fast-food chains, new and old, were duking it out. The cod Arthur Treacher’s used in its recipes doubled in price as a result of the 1975-1976 Cod War between Iceland and Britain. By the end of that decade, Arthur Treacher’s had filed for bankruptcy protection.

Today, only seven Arthur Treacher’s Fish & Chips restaurants remain: Three in the metro New York City area and four in northeast Ohio, where the chain was created. You can also find Arthur Treacher’s Fish & Chips products at other restaurant chains, including Nathan’s Famous.

Check out this vintage ‘70s Arthur Treacher’s Fish & Chips TV commercial.

Chi-Chi's

Chi-Chi’s was big on spicy food, from salsa and nachos to everything else Americans think of (chimichangas and fried ice cream anyone?), as Tex-Mex food. Created by former Green Bay Packers star Max McGee and restaurateur Marno McDermit, it launched in 1975 in the unlikeliest of places for a Mexican food chain: downtown Minneapolis.

The timing was perfect, with Mexican food a trendy choice for diners at that time. Chi-Chi’s took off, growing to 237 locations by 1986. But increased competition and a slew of unfortunate events spelled the chain’s demise: The number of location slipped to 144 by 2002; Chi-Chi’s filed for bankruptcy in 2003; and a month after that filing, tainted green onions imported from Mexico and served at a Chi-Chi’s near Pittsburgh caused a hepatitis A outbreak that sickened 636 people and killed four.

The U.S. chain never recovered, though there are Chi-Chi’s restaurants in Europe, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. And you can still find Chi-Chi’s-branded products, owned by Hormel, in supermarkets.

Beefsteak Charlie's

An all-you-can-eat salad bar, plus unlimited beer and wine and massive portions of hamburgers, steaks, ribs and chicken at ridiculously low prices. What kind of business model is that?

Consider this review, from The Washington Post, in 1982:

“I stopped in at the Bethesda branch one cold Sunday with my daughter and her friend, a fellow shrimp fanatic,” wrote Pat McNees. “Exercising no restraint whatever, we polished off seven heaping plates of ‘shrimp cocktail’ from the salad bar, three salads, two orders of barbecued chicken, one sirloin steak Mediterranean with garlic sauce, three pitchers of soft drink, one baked potato, two orders of potato chips, and two dishes of ice cream--for a grand total of $12.49 (plus a $3 tip). And I turned down the free beer (Schaeffer's) and wine (Franzia) that come with each adult dinner, which would have made it even more of a bargain.”

But that was indeed the recipe in 1976 when restaurateur Larry Ellman rebranded his Steak & Brew chain Beefsteak Charlie’s, named for a classic, long-ago Manhattan restaurant. The chain grew to 60 East Coast locations. It was acquired by Bombay Palace Restaurants, and by 1989, only 35 locations remained when that group filed for bankruptcy. By the early 2000s, all of the remaining Beefsteak Charlie’s were shuttered.

Here’s a Beefsteak Charlie’s commercial from the 1980s.

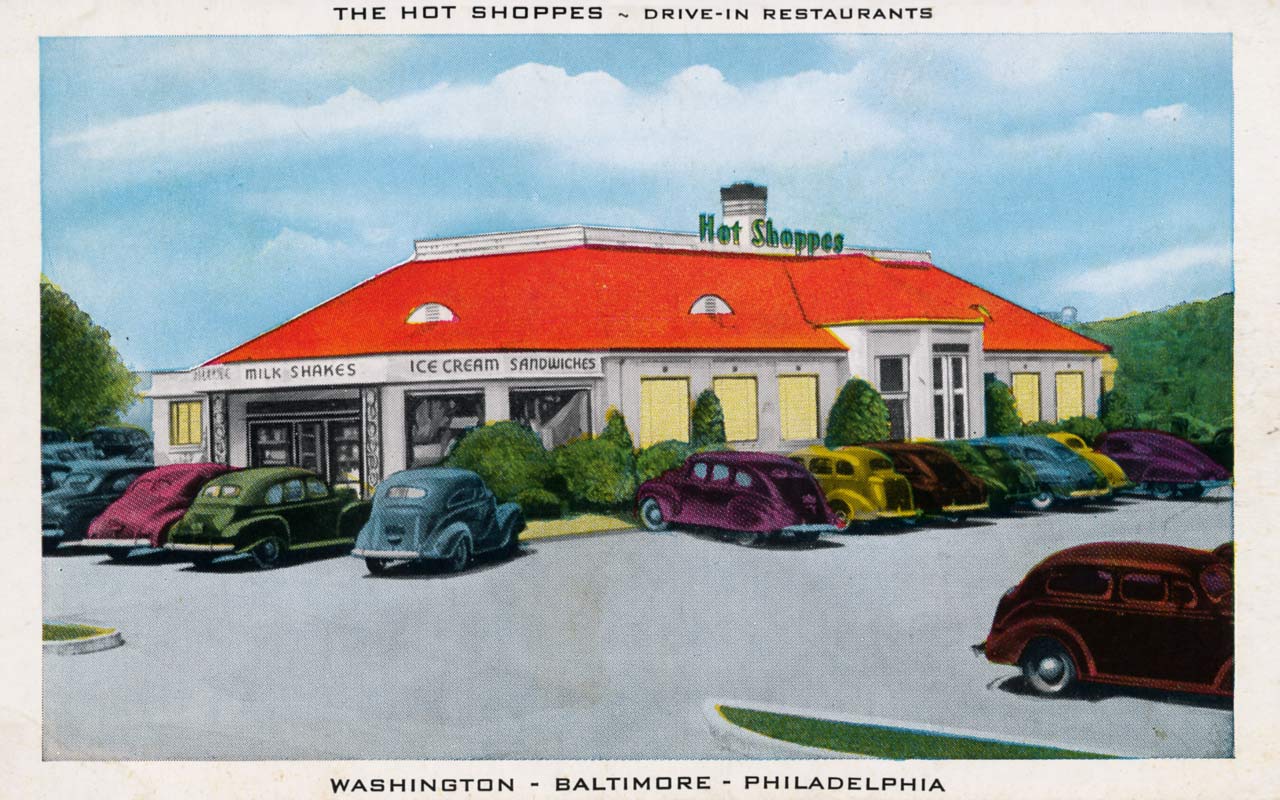

The Hot Shoppes

The Hot Shoppes was the first Washington, D.C. hospitality venture for a family with a famous name: Marriott.

J. Willard Marriott opened the first Hot Shoppe in 1927. (The company’s first hotel didn’t open for another 30 years.) The food-for-the-family chain grew to 70 locations by 1960, settling in seven states and D.C. But to the dismay of many fans, Marriott Corp. began closing the restaurants in the 1990s, shuttering the last Hot Shoppe in 1999.

What was the appeal? Fresh-made food, as this 1968 Hot Shoppes commercial touts, and plenty of it, including a sumptuous buffet bar. There were signature items, too, including the Mighty Mo triple-decker hamburger, the Orange Freeze tart milkshake, and the Teen Twist ham-and-cheese sandwich topped with tartar sauce.

But don’t get hangry over this food nostalgia. Marriott Corp.’s flagship hotel in D.C., the Marriott Marquis, hosts Anthem, a Hot Shoppes-inspired restaurant that still serves some of the original restaurant’s favorites. We checked.

Burger Chef

There was a time – the late 1960s and early 1970s – when Burger Chef, founded in the Midwest in 1958, was the second-largest restaurant chain in the country, only slightly behind its biggest competitor, McDonald’s.

Burger Chef’s formula was simple – and easily replicated by McDonald’s and others in the years that followed: Focus on hamburgers, fries and milkshakes. Burger Chef also pioneered the “Fun Meal” for kids in 1973, offering a small hamburger, fries, drink and dessert, along with a small toy. (McDonald’s created the similar Happy Meal six years later.) At its peak, in 1972, Burger Chef operated 1,200 restaurants, slightly behind McDonald’s at 1,600.

Burger Chef was sold in 1982 to another burger competitor, Hardee’s, which swallowed the remaining 600 or so restaurants and eventually made them disappear (revived as a plot point in “Mad Men”). The last Burger Chef franchise, in Tennessee, closed in 1996.

Steak and Ale

The dimly lit chain was born in 1966 in Dallas, founded by restaurant sensation Norman Brinker (who later developed the red-hot Chili’s restaurant chain). Steak and Ale, which peaked in 1992 with 157 restaurants, had a decent run through the last half of the 20th century ( watch this 1978 commercial). But in July 2008, the corporate Steak and Ale restaurants were abruptly closed (as were the Bennigan’s sister restaurants) after a Chapter 7 bankruptcy filing by S&A Restaurant Corp., owner of both chains at the time.

A comeback is on the table: Dallas-based Legendary Restaurant Brands, which bought the rights to the Steak and Ale and Bennigan’s brands in 2015, plans to roll out the brand once again and is looking for franchisees. They have a prototype design for Steak and Ale (hint: more light, less dark).

Not all are optimistic. "I would say it's a long shot for this brand to regain that [peak] level of sales," Darren Tristano, president of restaurant research firm Technomic, told the Dallas Morning News. "But likely they can build as a regional brand and leverage nostalgia and boomer consumers who remember and grew up with the brand."

Kenny Rogers Roasters

A quick lesson for the kiddos: Kenny Rogers (no relation to Roy) is a real person, a country singer who got into the restaurant business in 1991 with partner John Y. Brown Jr., a former Kentucky governor and former KFC CEO. The specialty was wood-fired rotisserie-roasted chicken, as well as turkey and ribs.

At its zenith, the chain operated 450 outlets in North America, Asia and the Middle East.

Kenny Rogers Roasters filed for bankruptcy in 1998, then was purchased by Nathan’s, which rolled some of the Kenny Rogers Roasters products onto its menu. According to its website, the brand is now owned by a Malaysian company, still operates in the Middle East and Asia, and lives on in infamy as a Kramer-centered plot device in this classic 1996 “Seinfeld” episode.

Gino's Hamburgers

Gino’s may very well have been one of the first sports-themed restaurants, named for NFL Hall of Famer Gino Marchetti, who was a co-owner. Founded in 1957 in Dundalk, Md. near Baltimore, where Marchetti had played for the Baltimore Colts, the fast-food chain was known for its signature burgers, including the Gino Giant and the Sirloiner. It was also known for its television and radio commercials (often featuring comedian Dom DeLuise), including the jingle “Everybody goes to Gino’s, ‘cause Gino’s is the place to go.”

By 1981, Gino’s had grown to 313 outlets, from New Jersey to northern Virginia, and the company also owned 43 Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurants and 113 Rustler Steak Houses. Acquired by Marriott in 1982, the Gino’s name soon disappeared as Marriott rebranded more than 100 Gino’s to its Roy Rogers brand.

In 2010, Marchetti and other principals with the original Gino’s engineered a Gino’s comeback, as Gino’s Burgers & Chicken. There are two locations, in Glen Burnie, Md., and Towson, Md.

Farrell's Ice Cream Parlour

If you ever ventured into a Farrell’s Ice Cream Parlour, the experience is stamped in your psyche: A restaurant decorated like the early 1900s, with wait staff wearing period clothing (including straw skimmer hats), servers bringing giant bowls of ice-cream sundaes on a stretcher (after they ran wildly around the restaurant), drums beating, bells ringing and sirens blaring, wait staff singing, and a player piano constantly playing. Pure cacophony and sweet-treat over-indulgence, as you can see in this commercialfrom 1980.

The formula – burgers, sandwiches, and lots of ice cream chosen from a menu shaped like a tabloid newspaper -- worked for a while for the chain that started in Portland, Ore., in 1963. By the early 1970s, Farrell’s had grown to 58 locations nationwide. It was sold to Marriott Corp. in 1972, which grew Farrell’s to 130 stores. Marriott sold the rights to the chain to an investment group in 1982. An attempt to reshape the chain resulted in bankruptcy, and the brand went back into the hands of Marriott, which closed most of the stores.

One Farrell’s Ice Cream Parlour remains open, in Southern California. It’s owned by self-made millionaire investor Marcus Lemonis of CNBC’s “The Profit.”

Lum's

Beer-soaked hot dogs? Two, please! Alas, Lum’s didn’t last. The family restaurant chain, born in Miami Beach, Fla., in 1956, liquidated in 1982.

And, indeed, hot dogs soaked in beer were the signature dish of Lum’s, along with beer, fried seafood and hamburgers. At its height in the 1970s, Lum’s had 450 restaurants in the U.S. and abroad, and employed comedian Milton Berle for its TV commercials.

After a couple of changes in ownership, Lum’s began to struggle. In 1982, when Lum’s corporate offices operated 70 Lum’s restaurants in the eastern U.S., the company filed for Chapter 11 protection from its creditors and largely disappeared.

White Tower

White Tower no-frills diners numbered 230 in the chain’s heyday, the 1950s. The concept, born in Milwaukee in 1926, mimicked a close competitor, White Castle (yes, there was a legal tussle, and White Castle won), both with an emphasis on square, steam-cooked burgers smothered in onions and sold by the sack, and architecture that made small-box stores look like medieval castles, complete with fake turrets. White Tower was essentially making sliders before sliders were cool.

Past the 1950s, White Tower, its restaurants mostly relegated to urban areas, began to fade away; it never made the move to the more lucrative suburbs, like many of its fast-food competitors did, with their accelerated growth in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Red Barn Restaurants

To stand out from the growing crowd of fast-food restaurants, Red Barn restaurants were built like a, well, red barn, with high ceilings inside and large windows.

Launched in Springfield, Ohio, in 1961, the chain grew to more than 400 restaurants in 19 U.S. states and Canada.

Red Barn’s menu featured hamburgers, chicken and fish, touted by the mascots Hamburger Hungry, Fried Chicken Hungry and Big Fish Hungry. It was one of the first fast-food chains to install a salad bar. (Here’s a commercial from the 1970s.)

But under Red Barn’s last set of owners, an investment group, Red Barn restaurants throughout the U.S. and Canada began to close when leases expired around 1988.

Bennigan's

The Irish-themed Bennigan’s bar and grill had a rocky run, a nearly full-on collapse, and is in the midst of a dramatic comeback.

The back story: Bennigan’s (as well as Steak and Ale) was created in Atlanta by legendary Dallas restaurateur Norman Brinker for the Pillsbury Corp. and later sold to other owners.

Known for its happy hours more than its food, the chain’s sudden near-collapse in 2008 was epic: Its owner filed for Chapter 7 liquidation, shuttering the 150 corporate-owned restaurants overnight (more than 100 franchises survived), as well as all of the Steak and Ale restaurants. Two years earlier, it had closed all of its New York state and Connecticut locations.

Analysts said Bennigan’s failed to distinguish itself from other fern bar players, including T.G.I. Fridays and Ruby Tuesday and couldn’t muster loyalty. Though it was an Irish-themed restaurant, its menu was similar to competitors: steak, tempura shrimp and Southwestern-style appetizers. (Here’s a Bennigan’s commercial from 1993.)

“All these bar and grill concepts are very, very similar,” Bob Goldin, executive vice president of Technomic, a restaurant industry consulting group, told The New York Times in 2008. “They have the same kind of menu, décor, appeal.”

There are currently 15 Bennigan’s restaurants in the U.S. and 18 in Mexico, South America and the Middle East. The current Bennigan’s are owned by Dallas-based Legendary Restaurant Brands, which is growing Bennigan’s (it also owns the Steak and Ale chain, which it’s trying to revive).

What Comfort-Food Chains Can Do to Survive

So how can current chains ride the sea changes in the restaurant business and avoid fading away?

Says Susskind, “Embrace technology -- apps, tabletop technology, giving them more control over service, ordering and payment. Companies that have done a good job with tech are having greater success.”

And? “Focus on things that resonate with [younger consumers]. Look at what Cracker Barrel has done with its fast-casual concept and its new push to have biscuit shops. They are taking a classic concept and reinventing it for younger consumers. It is working. Places that focus on fresh food, rather than mass-produced food, will resonate more. Restaurants that are seen as assembling food rather than preparing it will lose.”

Also, recent history has shown you can’t sustain a restaurant chain built on a fad, like the crepe-focused The Magic Pan, another flash-in-the-pan.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Bob was Senior Editor at Kiplinger.com for seven years and is now a contributor to the website. He has more than 40 years of experience in online, print and visual journalism. Bob has worked as an award-winning writer and editor in the Washington, D.C., market as well as at news organizations in New York, Michigan and California. Bob joined Kiplinger in 2016, bringing a wealth of expertise covering retail, entertainment, and money-saving trends and topics. He was one of the first journalists at a daily news organization to aggressively cover retail as a specialty and has been lauded in the retail industry for his expertise. Bob has also been an adjunct and associate professor of print, online and visual journalism at Syracuse University and Ithaca College. He has a master’s degree from Syracuse University’s S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications and a bachelor’s degree in communications and theater from Hope College.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayPresident Trump said he will decide within the next 10 days whether or not the U.S. will launch military strikes against Iran.

-

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K Senior Tax Deduction Means for Medicare IRMAA

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K Senior Tax Deduction Means for Medicare IRMAATax Breaks A new tax deduction for people over age 65 has some thinking about Medicare premiums and MAGI strategy.

-

U.S. Congress to End Emergency Tax Bill Over $6,000 Senior Deduction and Tip, Overtime Tax Breaks in D.C.

U.S. Congress to End Emergency Tax Bill Over $6,000 Senior Deduction and Tip, Overtime Tax Breaks in D.C.Tax Law Here's how taxpayers can amend their already-filed income tax returns amid a potentially looming legal battle on Capitol Hill.

-

What to Do With Your Tax Refund: 6 Ways to Bring Growth

What to Do With Your Tax Refund: 6 Ways to Bring GrowthUse your 2024 tax refund to boost short-term or long-term financial goals by putting it in one of these six places.

-

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should Know

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should KnowMedicare Part A and Part B leave gaps in your healthcare coverage. But Medicare Advantage has problems, too.

-

15 Reasons You'll Regret an RV in Retirement

15 Reasons You'll Regret an RV in RetirementMaking Your Money Last Here's why you might regret an RV in retirement. RV-savvy retirees talk about the downsides of spending retirement in a motorhome, travel trailer, fifth wheel, or other recreational vehicle.

-

The Six Best Places to Retire in New England

The Six Best Places to Retire in New Englandplaces to live Thinking about a move to New England for retirement? Here are the best places to land for quality of life, affordability and other criteria.

-

The 10 Cheapest Countries to Visit

The 10 Cheapest Countries to VisitWe find the 10 cheapest countries to visit around the world. Forget inflation and set your sights on your next vacation.

-

15 Ways to Prepare Your Home for Winter

15 Ways to Prepare Your Home for Winterhome There are many ways to prepare your home for winter, which will help keep you safe and warm and save on housing and utility costs.

-

Six Steps to Get Lower Car Insurance Rates

Six Steps to Get Lower Car Insurance Ratesinsurance Shopping around for auto insurance may not be your idea of fun, but comparing prices for a new policy every few years — or even more often — can pay off big.

-

How to Increase Credit Scores — Fast

How to Increase Credit Scores — FastHow to increase credit scores quickly, starting with paying down your credit card debt.