Benjamin Graham’s Timeless Advice

You don’t have to be a brilliant analyst like Graham to recognize the value in value today.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

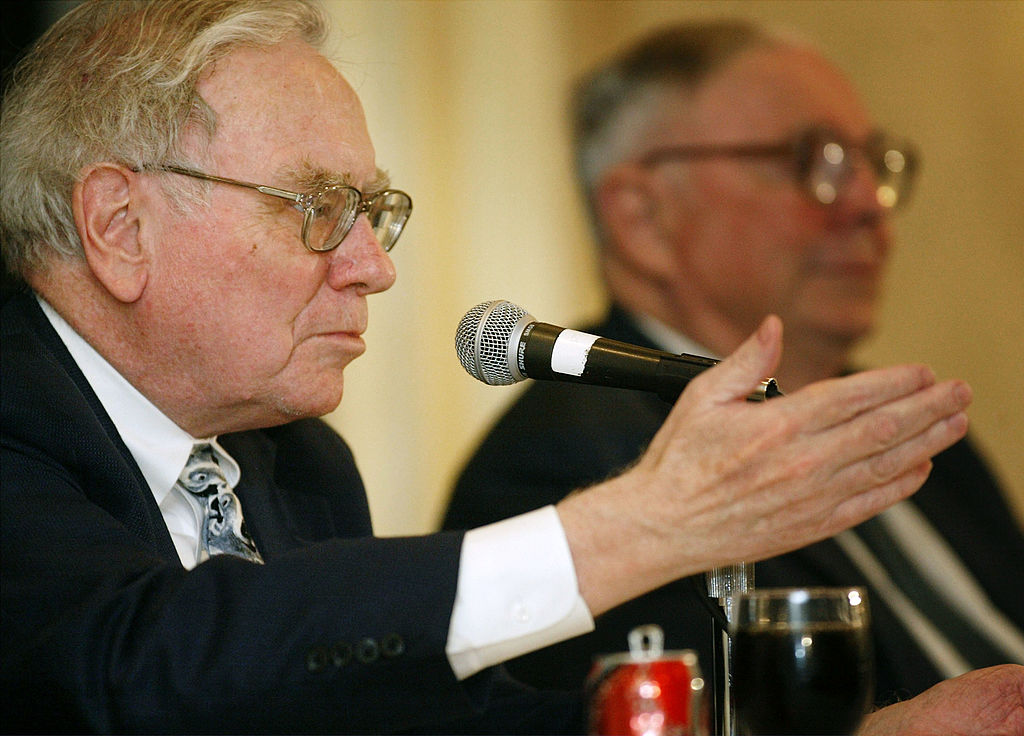

Benjamin Graham had all the traits of a great investor—brains, curiosity and discipline. An immigrant to New York, his family was plunged into poverty when his father died. But Ben was a smart kid. He learned to read six languages in high school and went on to attend Columbia University, where he became a Greek scholar and, on graduation, received offers to teach from three disparate departments: mathematics, philosophy and English. Instead, he chose Wall Street, eventually teaching at Columbia’s business school, where Warren Buffett was among his students.

Graham had several big ideas. One was that the stock market was susceptible to the same kind of rigorous study as any academic subject. The result was Security Analysis, the classic book he wrote in 1934 with David Dodd. Another big idea was that investors should strive to own stocks that are priced low enough that they provide a “margin of error.”

Extreme value can produce extreme gains. As Graham wrote in the 1964 edition of The Intelligent Investor (first published in 1949), “In many cases there may be less real risk associated with buying a ‘bargain issue’ offering the chance of a large profit than with a conventional bond.”

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

You don’t have to be a brilliant analyst like Graham to recognize the value in value today. A study by Fidelity found that over the 26-year period through 2015, large-cap value stocks returned 9% compared with 8.6% for large-cap growth. Since then, however, growth has clobbered value.

Over the past three years, for example, Vanguard Russell 1000 Growth, an exchange-traded fund geared to a broad growth-stock index, has returned an annual average of 20.4%. Vanguard Russell 1000 Value (symbol VONV, $120) has returned just 9.6% annually. Value seems to be particularly undervalued right now. (Stocks and funds I like are in bold. Prices and returns are through December 31.)

Or simply check out the portfolio of Dodge & Cox Stock (DODGX), a superb large-cap value fund. Top holdings include Wells Fargo (WFC, 54), a venerable financial company beset by recent management turmoil, and Occidental Petroleum (OXY, $41), whose shares are down by nearly half since May 2018.

Other value-oriented mutual funds to consider include Homestead Value (HOVLX), whose top 10 holdings include Parker-Hannifin (PH, $206), a company that sells all kinds of monitoring equipment; Janus Henderson Small Cap Value (JSCVX), which has been loading up on financial-services stocks; and T. Rowe Price Equity Income (PRFDX), which owns value stocks that pay good dividends, including The Southern Co. (SO, $64), the Atlanta-based electric utility, now yielding close to 4%.

The big idea. Graham’s third—and perhaps most important—idea involved psychology. He wrote in The Intelligent Investor, “The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.” Here, he was ahead of his time. The rise of behavioral economics in recent years has shown that people often make financial decisions irrationally. For example, investors tend to devote more of their portfolio to stocks when shares have run up than when prices have fallen. By contrast, shoppers are more attracted to sweaters when they go on sale.

How do we protect ourselves against our own worst instincts? The best answer is dollar-cost averaging, investing the same amount of money regularly in the same bundle of stocks or mutual funds—or, for that matter, in a single index fund such as ETF SPDR S&P 500 (SPY, $322) or Schwab Total Stock Market (SWTSX).

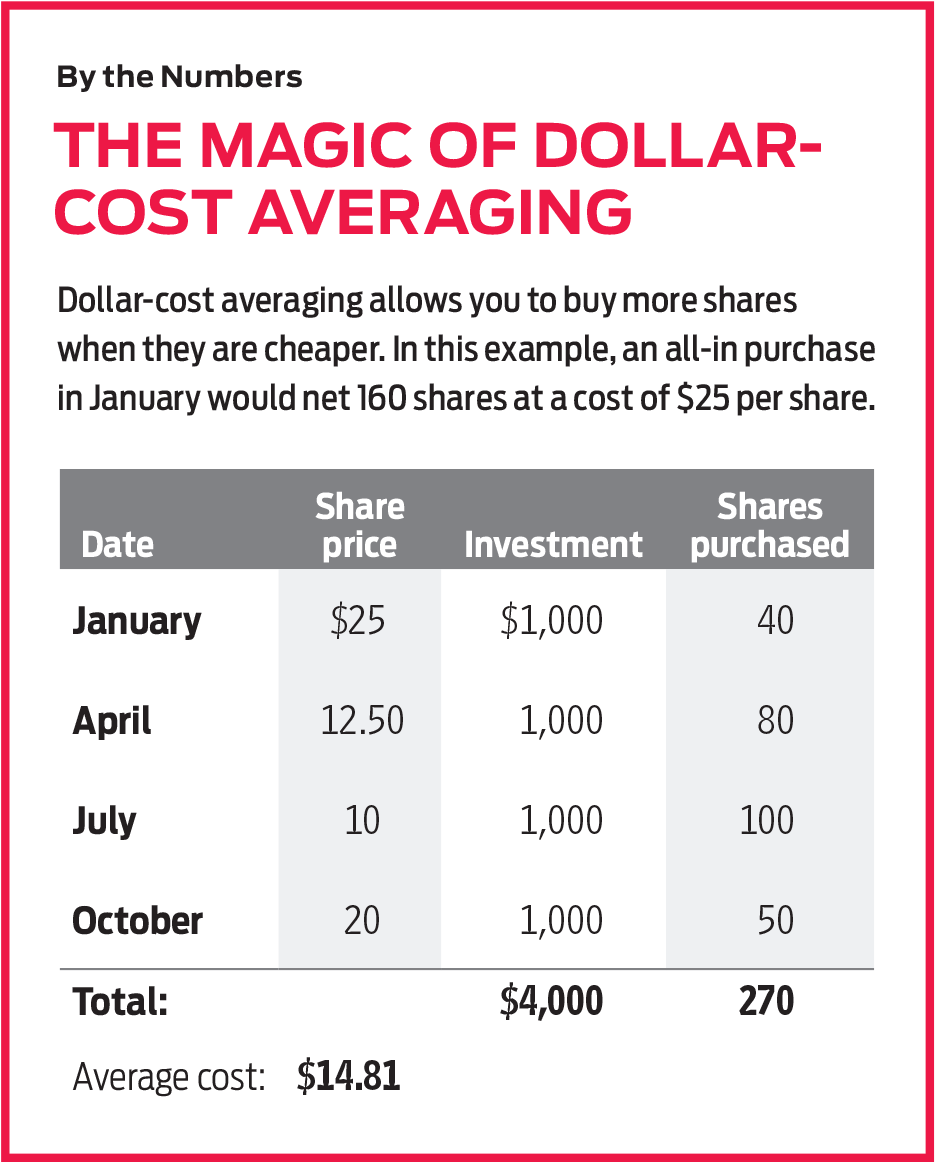

Here’s an example: Assume you tell your bank to transfer $1,000 every quarter to a broker who is instructed to use it all to buy shares in a single stock. At the start of the first quarter, the market price of the stock is $25, so your $1,000 buys 40 shares (I’m leaving out transaction costs to make the illustration simple). Three months later, the stock has collapsed to $12.50, so your $1,000 buys 80 shares. The next quarter, the stock drops to $10, so you get 100 shares. Then, it jumps to $20, so you buy 50. At the end of a year, the stock price ends where it began, at $25. You have invested $4,000 and own 270 shares for an average cost of $14.81 each. Had you invested $4,000 all at once at the start of the year, your cost per share would be $25.

Of course, in this example, the stock falls and then rebounds to its original price. If the stock shot straight up, you might have been better off making the all-in investment. But the danger for investors comes not in a sharply rising market, when it’s easy to stay invested, but in a falling market, when the impulse is to bail out. Dollar-cost averaging allows you to view your investments in a completely different way. A falling stock price is not a calamity; in fact, it is a boon because it allows you to own a bigger chunk of the company.

It’s a rare investment that, at some point, does not fall below the price you paid for it. Graham emphasized both the likelihood and the transience of such declines. “The bona fide investor,” he wrote, “does not lose money merely because the market price of his holdings declines.” Investors lose money only if they actually sell at a loss.

The problem, as behavioral economists including Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler have pointed out, is that investors are “loss averse,” which means “that they are distinctly more sensitive to losses than to gains.” When investors combine loss aversion with a propensity to check the dollar value of their portfolios frequently, they end up making mistakes—such as purging their portfolios of perfectly good stocks at precisely the wrong time.

A better viewpoint. When you dollar-cost average, on the other hand, you focus more on the number of shares you own than on the daily prices of those shares. You think of yourself as accumulating a bigger stake in an excellent business—or, if you own a broad-based mutual fund, in a time-tested economy.

“A serious investor,” Graham wrote, “is not likely to believe that the day-to-day or even month-to-month fluctuations of the stock market make him richer or poorer.” He’s right, but how many serious investors are there if we define serious as meaning immune to their own irrational impulses? Not many.

One solution Graham suggests is “some kind of mechanical method of varying the proportion of bonds to stocks in the investor’s portfolio.” If the market rises, the investor should “make sales out of his stockholdings, putting the proceeds into bonds; as it declines, he will reverse the procedure.” Graham advocates this strategy because it will give the investor “something to do” [Graham’s italics]; that is, it will “provide some outlet for his otherwise too pent-up energies.”

What Graham is describing is a form of regular portfolio rebalancing. Assume you decide on a mix of 60% stocks and 40% bonds. If, after a few years, the stock market rises 50% and bonds are flat, then just holding on to your assets gives you a new mix: 69% stocks and 31% bonds. But if you sell enough stocks and then use the proceeds to buy bonds, you’ll get back to 60-40.

I favor rebalancing, but I am a fanatic when it comes to dollar-cost averaging. Another advantage to this strategy is that it is a forced savings program. If a fixed amount comes out of your bank account each month or each quarter, you tend not to miss it because you never had it to spend. What a great way to tame your own worst enemy!

James K. GLassman chairs Glassman Advisory, a public affairs consulting firm. He does not write about his clients. He owns none of the stocks mentioned in this column. His most recent book is Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments In a Time of Turbulence.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

8 Boring Habits That Will Make You Rich in Retirement

8 Boring Habits That Will Make You Rich in RetirementThese mundane activities won't make you the life of the party, but they will set you up for a rich retirement. Discover the 8 boring habits that build real wealth.

-

QUIZ: Are You Ready To Retire At 55?

QUIZ: Are You Ready To Retire At 55?Quiz Are you in a good position to retire at 55? Find out with this quick quiz.

-

10 Decluttering Books That Can Help You Downsize Without Regret

10 Decluttering Books That Can Help You Downsize Without RegretFrom managing a lifetime of belongings to navigating family dynamics, these expert-backed books offer practical guidance for anyone preparing to downsize.

-

Vanguard Cuts Fund Fees Again. Here's Why That's Important for You

Vanguard Cuts Fund Fees Again. Here's Why That's Important for YouVanguard recently cut fees on dozens of ETFs and mutual funds, which is great news for investors. Here's why.

-

Best Mutual Funds to Invest In for 2026

Best Mutual Funds to Invest In for 2026The best mutual funds will capitalize on new trends that emerge this year, all while offering low costs and solid management.

-

What Made Warren Buffett's Career So Remarkable

What Made Warren Buffett's Career So RemarkableWhat made the ‘Oracle of Omaha’ great, and who could be next as king or queen of investing?

-

With Buffett Retiring, Should You Invest in a Berkshire Copycat?

With Buffett Retiring, Should You Invest in a Berkshire Copycat?Warren Buffett will step down at the end of this year. Should you explore one of a handful of Berkshire Hathaway clones or copycat funds?

-

Stocks at New Highs as Shutdown Drags On: Stock Market Today

Stocks at New Highs as Shutdown Drags On: Stock Market TodayThe Nasdaq Composite, S&P 500 and Dow Jones Industrial Average all notched new record closes Thursday as tech stocks gained.

-

Trump's Economic Intervention

Trump's Economic InterventionThe Kiplinger Letter What to Make of Washington's Increasingly Hands-On Approach to Big Business

-

9 Warren Buffett Quotes for Investors to Live By

9 Warren Buffett Quotes for Investors to Live ByWarren Buffett transformed Berkshire Hathaway from a struggling textile firm to a sprawling conglomerate and investment vehicle. Here's how he did it.

-

A Timeline of Warren Buffett's Life and Berkshire Hathaway

A Timeline of Warren Buffett's Life and Berkshire HathawayBuffett was the face of Berkshire Hathaway for 60 years. Here's a timeline of how he built the sprawling holding company and its outperforming equity portfolio.