The Rule of Two Lives in Retirement

The 'rule of two lives in retirement' means accounting for your partner at every decision point, because one life becomes two.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Marriage may be the union of two people becoming one — but in retirement, that math doesn’t work.

In this instance, one becomes two. That’s because every financial decision you make with your retirement savings doesn’t just affect you. It affects your spouse, too. And the two of you likely won’t share the same timeline, health needs. or lifestyle preferences as you age.

Planning for two lives introduces complexity. And not all couples are on the same page. According to a 2024 Fidelity Investments study, more than half (53%) of couples who haven’t yet retired disagree on how much they’ll need to save.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Yet, it’s not just about how much you save, but also how you use what you’ve saved. You need to think for two. Hence, the “rule of two lives in retirement” means accounting for your partner at every decision point: from pensions and Social Security to withdrawal strategies and emotional well-being.

Here’s where it matters most and how planning for both lives can make retirement more secure, purposeful and supportive for each of you.

Optimizing for longevity

Combining assets as a couple can create a sizeable nest egg, but it doesn’t eliminate one of the biggest risks in retirement: living longer than your money.

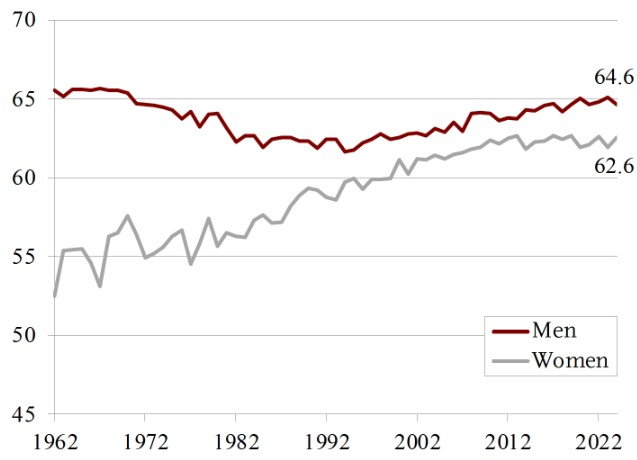

The timing of retirement is often a shared decision. For instance, consider that on average, men retire at age 64 and women at 62, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Longevity, on the other hand, is a wild card. It’s not only harder to predict, but it’s also likely to differ between partners, depending on personal factors such as family history.

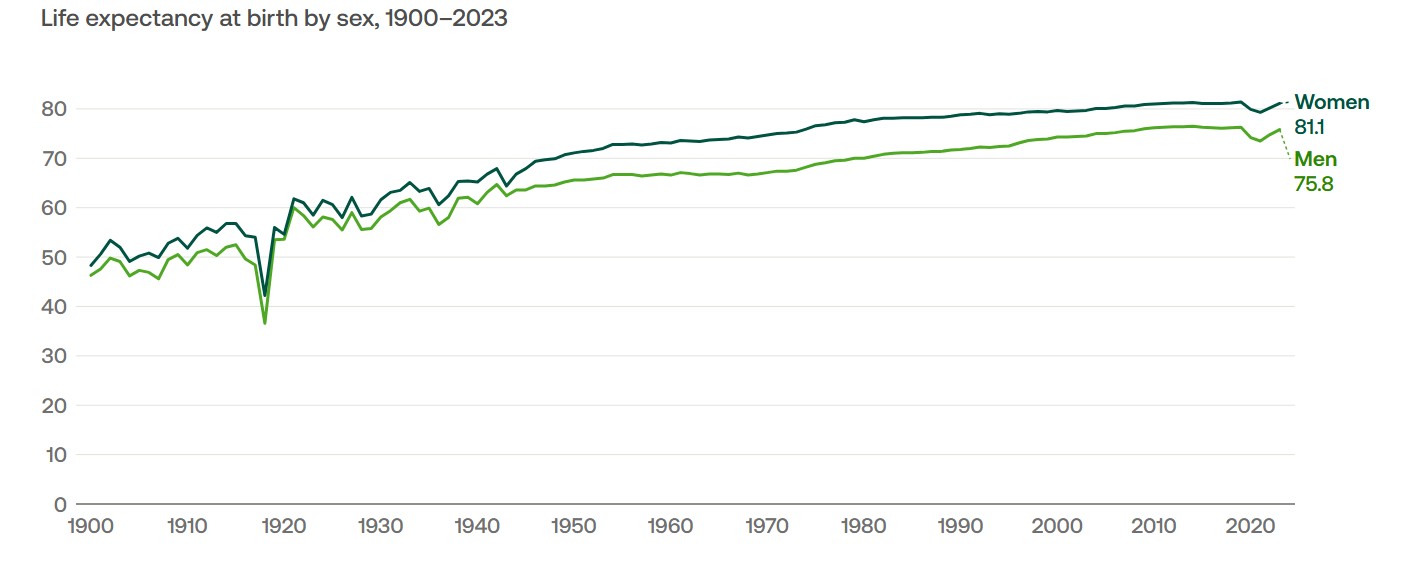

Although the average age of retirement for men and women has been trending closer together, it's important to note that average longevity still remains years apart for mixed sex couples. The average life expectancy for men in the U.S. is 75.8 years, compared to 81.1 years for women. Both figures may understate the actual years you have left. Thanks to rising lifespans and medical advances, the global centenarian population is expected to swell to 3.7 million by 2050.

In other words, living well into your 90s may not be the exception, but the rule. That’s why couples should plan for the longest likely lifespan, not just the average.

Too often, however, retirement plans focus on income rather than age. Melissa Caro, CFP® and founder of My Retirement Network, flags this common trap: “The mistake is building a plan entirely around the ‘primary’ earner or assuming the survivor will seamlessly execute the ‘rational’ decisions you mapped out together years earlier. Reality is messier.”

Age gaps, health disparities and differences in risk tolerance between spouses can have real consequences for drawdown strategies, asset allocation and insurance planning.

“Your financial plan must last as long as either spouse does,” says Patrick Huey, owner and principal adviser of Victory Independent Planning. “Often, this means stress-testing the portfolio out 30-plus years, especially if there’s an age gap or strong longevity in the family.”

Decisions around survivor benefits and taxes

Some retirement benefits force you to make a fundamental choice: should they cover one life or two? That’s the core of survivor benefits.

This is especially critical for couples who still have access to a pension. Pension plans typically offer two options: a single-life annuity, which pays the highest monthly benefit but ends when the pension holder dies; or a joint-and-survivor annuity, which provides a reduced benefit that continues for the life of the surviving spouse.

While the joint option may seem like the safest route, there are strategies that might offer more flexibility and even greater long-term value.

“With pensions, I sometimes recommend choosing the higher single-life payment and using the extra monthly income to purchase a permanent life insurance policy on the pension holder,” says Huey. “This approach provides both flexibility and, often, more lifetime value than a built-in survivor pension.”

Survivor planning also requires thinking ahead about taxes. When one spouse dies, the surviving partner often moves from the more favorable “married filing jointly” status to “single,” says Deva Panambur, CFP® and founder of Sarsi. That change can push the survivor into a higher tax bracket, known as the “widow’s penalty,” especially if large pretax accounts and required minimum distributions are involved.

Panambur recommends proactive steps: “Roth conversions can help reduce future required distributions. You can also be strategic with asset location, such as placing unrealized losses in the account of the longer-living spouse, and unrealized gains in the account of the spouse with shorter life expectancy.”

Timing Social Security

One of the major advantages of being married in retirement is having two sets of Social Security benefits to work with. That opens the door to more flexibility and strategy when deciding when each spouse should claim.

For example, a lower-earning spouse may be eligible for a spousal benefit worth up to 50% of the higher earner’s full retirement benefit. And if one spouse passes away, the surviving spouse can typically switch to a survivor benefit based on the deceased spouse’s earnings record, if it’s higher than their own.

“Social Security planning needs to account for which benefit survives,” says Panambur. “If the spouse with lower life expectancy also has the higher benefit, that can still be a strong case for delaying benefits because the higher check lives on.”

For many couples, delaying the higher earner’s benefit as long as possible can provide the greatest long-term security, even if it means tapping other resources in the short term.

“After one spouse dies, the survivor keeps the larger of the two benefits,” explains Huey. “So maximizing that one provides support for the spouse who may live alone the longest. And remember, one Social Security check disappears, joint costs don’t always get cut in half and taxes can jump.’”

Preparing financially and emotionally for the loss of one

Of all the challenges retirement presents, the most difficult to experience and to prepare for is the loss of a spouse.

The financial consequences can be significant. A 2020 Chicago Federal Reserve study found that spousal death leads to a persistent decline of about 11% in a surviving individual’s annual income.

But the emotional toll often cuts even deeper.

Losing a partner later in life has been linked to declines in both physical and mental health, and even an increased risk of death. According to the National Institute on Aging, grieving spouses should seek out emotional support, stay active in things they enjoy and care for their health.

Still, those steps are rarely easy, especially when the survivor is suddenly responsible for all major decisions on their own.

“I encourage budgeting for a transition period — ideally a year — where the survivor has the financial breathing room,” says Caro. “That buffer protects them from being forced into major decisions at the worst possible time.”

Practical preparation is just as important as emotional resilience. Caro adds that documentation is often the biggest missing piece. “One spouse almost always runs point on the household finances. It’s ideal if couples can organize and share this information as if they were running a small business: accounts, logins, service providers, pension details and any hidden life insurance attached to old benefits.”

And beyond the spreadsheets, there’s meaning to consider.

“I think the most critical piece of advice that I tell clients is to spend their money appropriately,” says Collin Lyon, CFP® and wealth strategy advisor at Anderson Financial Strategies. “What I mean by this is they spend their money on the things that bring real value to their lives. The mourning period is easier to digest when you’ve spent money on the trips with friends you can now lean on, or you’ve given to causes and communities that you’re still part of. It turns the survivorship conversation into a talk about how they can thrive while they are still living.”

Read More Retirement Rules

- The '120 Minus You Rule' of Retirement

- The Retirement Rule of $1 More

- The 'First Year of Retirement' Rule

- The Y Rule of Retirement: Why Men Need to Plan Differently

- The Rule of 240 Paychecks in Retirement

- The 'Die With Zero' Rule of Retirement

- The '8-Year Rule of Social Security' — A Retirement Rule

- The Kevin Bacon Rule of Retirement

- The Rule of Retirement Inversion

- The Rule of 1,000 Hours in Retirement

- The 'Second Law' of Retirement Rules

- The Rule of Four Futures

- The Rule of $1,000: Is This Retirement Rule Right for You?

- The Rule of 55: One Way to Fund Early Retirement

- The 80% Rule of Retirement: Should This Rule be Retired?

- The 4% Rule for Retirement Withdrawals Gets a Closer Look

- The Rule of 25 for Retirement Planning: How Much Do You Need to Save?

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Jacob Schroeder is a financial writer covering topics related to personal finance and retirement. Over the course of a decade in the financial services industry, he has written materials to educate people on saving, investing and life in retirement.

With the love of telling a good story, his work has appeared in publications including Yahoo Finance, Wealth Management magazine, The Detroit News and, as a short-story writer, various literary journals. He is also the creator of the finance newsletter The Root of All (https://rootofall.substack.com/), exploring how money shapes the world around us. Drawing from research and personal experiences, he relates lessons that readers can apply to make more informed financial decisions and live happier lives.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

AI Sparks Existential Crisis for Software Stocks

AI Sparks Existential Crisis for Software StocksThe Kiplinger Letter Fears that SaaS subscription software could be rendered obsolete by artificial intelligence make investors jittery.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the 'Medigap Trap?'

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the 'Medigap Trap?'Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

We Retired at 62 With $6.1 Million. My Wife Wants to Make Large Donations, but I Want to Travel and Buy a Lake House.

We Retired at 62 With $6.1 Million. My Wife Wants to Make Large Donations, but I Want to Travel and Buy a Lake House.We are 62 and finally retired after decades of hard work. I see the lakehouse as an investment in our happiness.

-

Social Security Break-Even Math Is Helpful, But Don't Let It Dictate When You'll File

Social Security Break-Even Math Is Helpful, But Don't Let It Dictate When You'll FileYour Social Security break-even age tells you how long you'd need to live for delaying to pay off, but shouldn't be the sole basis for deciding when to claim.

-

I'm a Wealth Adviser Obsessed With Mahjong: Here Are 8 Ways It Can Teach Us How to Manage Our Money

I'm a Wealth Adviser Obsessed With Mahjong: Here Are 8 Ways It Can Teach Us How to Manage Our MoneyThis increasingly popular Chinese game can teach us not only how to help manage our money but also how important it is to connect with other people.

-

Global Uncertainty Has Investors Running Scared: This Is How Advisers Can Reassure Them

Global Uncertainty Has Investors Running Scared: This Is How Advisers Can Reassure ThemHow can advisers reassure clients nervous about their plans in an increasingly complex and rapidly changing world? This conversational framework provides the key.

-

5 Ronald Reagan Quotes Retirees Should Live By

5 Ronald Reagan Quotes Retirees Should Live ByThe Nation's 40th President's wit and wisdom can help retirees navigate their financial and personal journey with confidence.

-

We're 78 and Want to Use Our 2026 RMD to Treat Our Kids and Grandkids to a Vacation. How Should We Approach This?

We're 78 and Want to Use Our 2026 RMD to Treat Our Kids and Grandkids to a Vacation. How Should We Approach This?An extended family vacation can be a fun and bonding experience if planned well. Here are tips from travel experts.

-

Should You Jump on the Roth Conversion Bandwagon? A Financial Adviser Weighs In

Should You Jump on the Roth Conversion Bandwagon? A Financial Adviser Weighs InRoth conversions are all the rage, but what works well for one household can cause financial strain for another. This is what you should consider before moving ahead.