If You're 65 and Still Working, Avoid Pitfalls and Maximize Benefits

If you plan to delay retirement, watch out for these benefit traps.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

If saving enough money to retire comfortably is a math problem, working longer is the easiest way to solve it. And some people in their mid sixties simply aren’t ready to give up a career they love. But although the benefits of working longer usually eclipse the drawbacks, older workers face a number of minefields, including penalties when they take Social Security early or sign up for Medicare late, and unexpected taxes on money in their retirement accounts.

At age 65, Thomas Kaiser, an instructor at Thomas Aquinas College in Santa Paula, Calif., is embarking on a new phase of his academic career. He has been tapped to serve as associate dean of a second campus in western Massachusetts, after the project receives approval from the state.

Kaiser was a member of Thomas Aquinas’s first graduating class in 1975, and he was the first of the private liberal arts college’s tutors—what the school calls its professors—to teach all 23 courses in the school’s classical curriculum, which focuses on the great books of the western world. “I don’t consider this a job,” Kaiser says. “It’s more like a calling. It’s something you get better at as time goes on.”

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

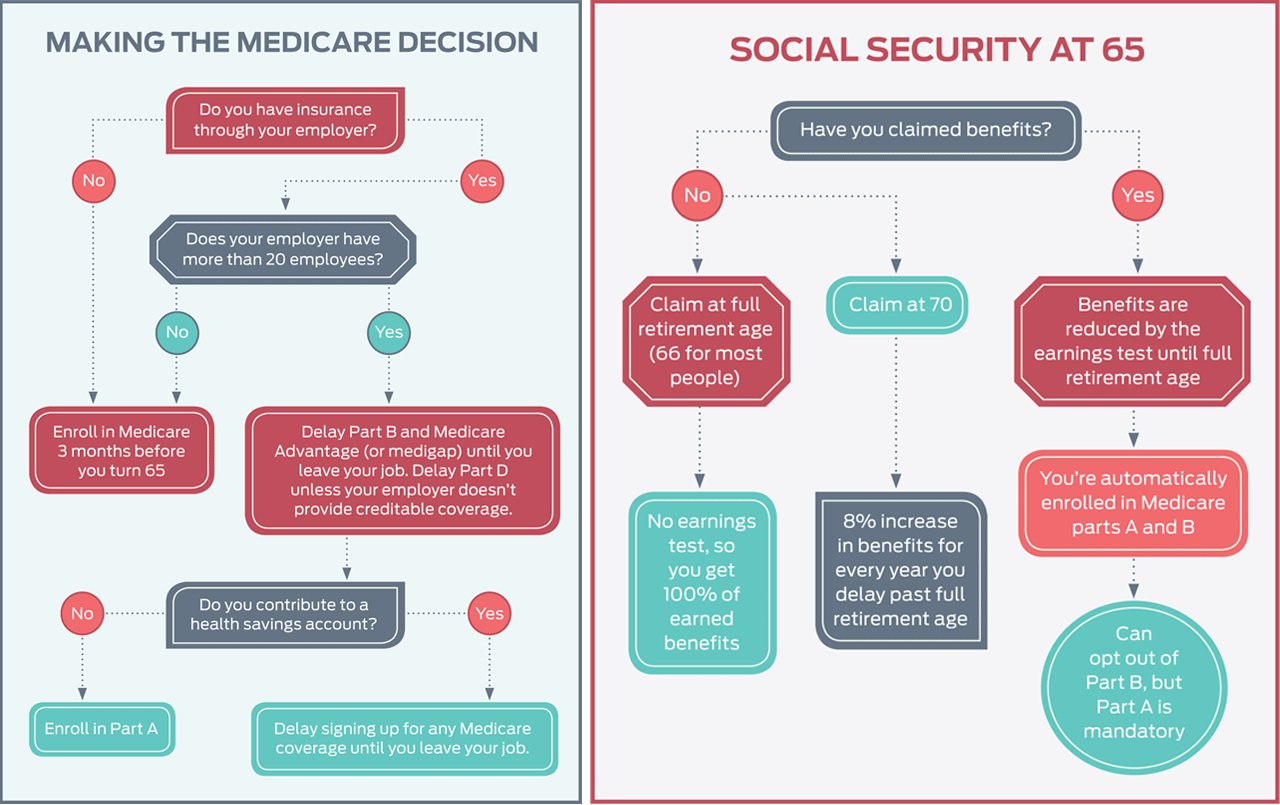

He hasn’t decided when he’ll retire, but he hopes to work until age 70, and he is considering filing for Social Security benefits when he turns 66. Waiting until full retirement age (66 for people born between 1943 and 1954) to claim Social Security will enable Kaiser to avoid the annual earnings test, which affects workers who claim benefits before they’ve reached full retirement age.

Although at one time older workers may have seemed out of place in the employee cafeteria, their numbers are growing fast. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that 36% of people between the ages of 65 and 69 will be working by 2024, up from 22% in 1994.

Still, many retirement programs and human resources departments don’t take into account the growing number of people who want to work beyond their mid sixties. If you want to stay on the job after age 65, you’ll need advice on how to maximize your benefits and avoid the traps, which include losing money because of the earnings test, paying penalties for failing to coordinate employer health benefits with Medicare, and getting hit with a tax bill once you turn 70 and are required to start taking money out of tax-deferred retirement plans.

Social Security

It often makes sense to delay taking Social Security until you stop working (or until you turn 70, whichever comes first). Why? One good reason is to avoid the earnings test. If you claim Social Security before you reach full retirement age, in 2018 your benefits will be reduced by $1 for every $2 you earn over $17,040. In the year you reach full retirement age, you’ll give up $1 in benefits for every $3 you earn over $45,360. In the month you reach full retirement age, the earnings test disappears. The test applies only to wages from a job or self-employment income; investment income, pension benefits and money withdrawn from your retirement savings aren’t counted.The benefits you give up due to the earnings test aren’t lost forever, though. Once you reach full retirement age, the Social Security Administration will adjust your benefits so that you’ll recoup the amount that was withheld. For example, suppose you retire at 62, file for benefits and later go back to work, forfeiting 12 months of payments by the time you turn 66. When Social Security recalculates your benefits, you’ll be treated as if you claimed them three years early instead of four. So instead of taking a 25% haircut in your payments, which is what happens if you claim at age 62, your benefits will be reduced by 20%.

Still, that 20% reduction will continue for as long as you claim Social Security. By waiting until you reach full retirement age, you’ll receive 100% of the benefits you’ve earned. And if you continue to delay claiming benefits—which you may be able to afford to do if you’re working—you’ll receive an 8% increase in your payout for every year you forgo taking benefits after full retirement age, until you turn 70.

There are other compelling reasons to wait. For example, if you claim Social Security benefits while you’re working, you may owe taxes on some of your benefits. Depending on your provisional income, up to 85% of your benefits are subject to federal taxes; 13 states tax your benefits, too.

Your provisional income is based on your modified adjusted gross income—which includes wages from a job—plus half of your Social Security benefits and all of your tax-exempt income. If your provisional income is less than $25,000 and you’re single (or less than $32,000 if you’re married and file a joint return), you won’t owe taxes on your benefits. If your provisional income is between $25,000 and $34,000 (or between $32,000 and $44,000 for married filers), up to 50% of your benefits may be taxable. If your provisional income is more than $34,000 if you’re single, or more than $44,000 if married filing jointly, up to 85% of your benefits may be taxable.

Longevity is an important consideration: The longer you expect to live, the more valuable those delayed benefits become.

Other types of income, such as pension payments and withdrawals from your IRAs and 401(k) plans, are also counted as provisional income, so many retirees end up paying taxes on their Social Security benefits even if they’re not working. But there are steps you can take to reduce taxable income from these sources. For example, withdrawals from a Roth IRA aren’t included in your AGI, so you could convert money from your traditional IRAs to a Roth before you file for Social Security (you will owe taxes on any pretax contributions and earnings). But unless you decline the holiday bonus, you don’t have much control over income from a job.

Postponing Social Security benefits until age 70 could reduce the risk that you’ll outlive your money, because you’ll receive higher benefits for the rest of your life. Longevity is an important consideration: The longer you expect to live, the more valuable those delayed benefits become.

Amy Kaiser, 73, director of the St. Louis Symphony Chorus, postponed claiming benefits until she turned 70 and says she has no regrets about that decision. She has a 403(b) plan—a retirement savings plan for employees in the public and nonprofit sectors—but won’t receive a traditional pension when she retires. More significantly, she has a history of longevity in her family. Her father lived to be 107 and was retired for 40 years.

Kaiser says she has no intention of spending that much time in retirement. Her current contract runs through 2021. “If you’re doing something you love, it isn’t work,” she says. “I’m still invigorated by what I do.”

Medicare

If you’re already receiving Social Security benefits when you turn 65, you’ll automatically be enrolled in Medicare Part A and Part B. Enrollment in Part A is mandatory if you’re receiving Social Security. But if you have health insurance through your employer, you may want to opt out of Part B, which covers doctor visits and outpatient services and imposes a monthly premium. You’ll find instructions on how to opt out of Part B on your Medicare card.

If you work for a company that doesn’t provide health insurance or has fewer than 20 employees, or you’re self-employed, sign up for Medicare parts A and B three months before your 65th birthday, which is the earliest you can enroll. That way, you’ll receive benefits as soon as you’re eligible. Medicare Part A covers hospitalizations and doesn’t usually cost anything. Premiums for Part B range from $134 to $428.60 a month, depending on your income.

If you don’t have prescription drug coverage from another source, such as retiree health insurance, you should also sign up for Part D, which covers prescription drugs. Premiums vary depending on the plan you choose but average about $35 a month.

If you’re working for a company that provides health insurance and has 20 or more employees, your employer must offer you the same group health plan it offers all other employees. For that reason, you may want to delay signing up for Part B until you leave your job. Otherwise, you could end up paying monthly premiums to Medicare and premiums for your employer-provided coverage.

If your employer-provided plan covers prescription drugs, you may also want to wait to sign up for Part D until you leave your job. Before you make that decision, though, find out whether your employer’s coverage is determined to be creditable—which means it’s at least as good as the coverage you would get from Medicare’s standard Part D plan. Fortunately, most employer-provided health insurance plans that provide prescription drug coverage meet the creditable standard, says Casey Schwarz, senior counsel for the Medicare Rights Center, a nonprofit consumer organization.

Your employer is required to tell you whether your coverage meets the creditable standard. If your coverage falls short and you later sign up for Part D, you’ll pay a penalty. (Keep good records of your employer’s notices of creditable coverage in case you’re charged a penalty and need to appeal.) Once you leave your job, you’ll be eligible for a special enrollment period to sign up for Medicare. If you fail to sign up during this period, you could face penalties and gaps in your coverage.

The HSA problem

Many financial planners recommend signing up for Medicare Part A as soon as you turn 65, even if you have insurance through your job. For most seniors, Part A doesn’t cost anything, and it may pay for expenses your employer plan doesn’t cover. There is one caveat, though, if your employer-provided plan offers a health savings account: In order to contribute to an HSA, you must be enrolled in a high-deductible health plan, and you can’t be enrolled in any other health insurance plan, including Medicare. You can take withdrawals from an HSA while you’re enrolled in Medicare, but you can’t contribute to an account. If you do, you’ll owe income taxes on the contribution, plus a 6% excise tax.

The easiest way around this problem is to forgo contributions to an HSA once you turn 65. That way, you can go ahead and sign up for Part A without worrying about any overlap. However, if your employer contributes to workers’ HSAs or matches contributions—and many do—you could end up leaving some serious money on the table. The average employer contribution to an HSA is $474 for individual coverage and $801 for family coverage, according to a 2016 survey by United Benefit Advisors. In addition, an HSA provides a tax-efficient way to put aside money for deductibles and other health care costs that aren’t covered by your insurance.

Contributions to an HSA are pretax if they’re made through payroll deductions. Plus, the money grows tax-deferred, and withdrawals used to pay qualified medical expenses are tax-free. Unlike a flexible spending account for health care, which often must be depleted by the end of the year (or by a grace period), HSAs are portable. You can take your savings with you when you leave your job and use the money to pay for medical expenses that aren’t covered by Medicare. In 2018, workers who are 55 or older can contribute up to $4,450 to an HSA for individual health coverage.

In June 2017, Sandra Larson, 64, retired from her job as an engineer for the Iowa Department of Transportation so she could travel and spend more time with her family. Her retirement lasted only nine months. In April, she joined Stanley Consultants, an engineering consulting firm that helps government agencies and private companies design water, energy and transportation projects.

Larson, who worked for 29 years with the Iowa DOT, says her new position will provide an opportunity to work on different types of engineering initiatives. She doesn’t plan to retire again anytime soon. “I just don’t see the end of the horizon,” she says. “The work is everything I hoped for.”

Larson says she expects to delay filing for Social Security until age 70 and plans to postpone signing up for Medicare when she turns 65 so she can participate in the company’s health savings account. That’s an option for older workers, but there’s a hitch: If you sign up for Part A after your 65th birthday, Medicare coverage is retroactive for up to six months. That means you could still face penalties for contributing to an HSA while enrolled in Medicare, even if you wait until you quit your job to sign up.

Here’s how to get around this time-machine dilemma:• Discontinue contributions to your HSA at least six months before you leave your job. If you want to front-load your HSA contributions at the beginning of the year, as many workers do, prorate the amount you contribute to adjust for the number of months you’ll be eligible to contribute before Medicare kicks in, taking the retroactive period into account.

• After you leave your job and sign up for Medicare, file a Return of Excess Contribution form with your plan administrator to withdraw contributions made while you were covered by Medicare. You’ll owe income taxes on the money, but as long as you withdraw the amount of your excess contribution before the tax deadline (April 15 in 2019), along with any income you’ve earned on that money, you’ll avoid the 6% excise tax.

Keep the IRS at bay

Working longer allows your retirement savings to continue to compound and grow because you can use income from your job to pay living expenses. But Uncle Sam won’t let you shelter your tax-deferred savings indefinitely. Once you turn 70, you must take required minimum distributions from traditional IRAs and former employers’ 401(k), 403(b) and other retirement plans. The amount you’ll be required to withdraw will be based on the balance in each of your tax-deferred accounts at the end of the previous year and a life-expectancy factor determined by the IRS.

Withdrawals are taxed at your ordinary income rate. If you’re still employed at age 70, the combined income from your RMD and your paycheck could push you into a higher tax bracket. It could also trigger higher Medicare premiums and increase taxes on your Social Security benefits.

There is, however, a useful exception to this requirement: If you’re still working, you don’t have to take RMDs from your employer’s 401(k) plan unless you own 5% or more of the company. If your employer allows you to roll over your former employers’ 401(k) plans into your current plan, you can delay taking RMDs from those accounts, too, says Daniel Galli, a certified financial planner in Norwell, Mass. Some employers also allow rollovers of traditional IRAs into their 401(k) plans, he says.

Have the money transferred directly from your former employers’ 401(k) plans and your IRAs into your current 401(k) to avoid a tax bill or penalty on the rollover. Do this before you turn 70 or you’ll be required to take RMDs before you roll over the money to your current employer’s 401(k) plan. Once you stop working, you’ll have to start taking RMDs.

Lower your RMDs

If you’re still working at age 70 but can’t delay required minimum distributions by consolidating retirement accounts in your current employer’s 401(k) account—because your employer doesn’t offer a 401(k) plan or doesn’t allow rollovers—there are other steps you can take to reduce taxes on your RMDs. These tactics are available to all seniors, but they’re particularly useful to older workers who don’t need to tap savings to pay living expenses.

Give your RMD to charity. Once you turn 70½, you can donate up to $100,000 from your IRA directly to charity every year. The donation will count as your RMD and won’t be included in your adjusted gross income. That could help you avoid a high-income surcharge on your Medicare premiums and lower taxes on your Social Security benefits.

Invest in a QLAC. A qualified longevity annuity contract allows you to invest up to 25% of your IRA (up to a maximum of $130,000) in a deferred income annuity that begins payouts years after you retire. A 70-year-old man who invests $130,000 in a QLAC that starts payments at age 80 will receive a payout of about $28,000 a year for the rest of his life. But here’s the near-term payoff: The amount invested in a QLAC isn’t counted when calculating your RMD. For example, if you have $520,000 in an IRA at age 70 and invest $130,000 in a QLAC, your RMDs would be based on $390,000. Once you start taking income from the annuity, it will be taxed, along with your other RMDs. But by that time, your tax rate should be lower because you probably won’t be working anymore.

Timing is everything

Meet the Medicare deadlines

Once you leave your job, you’re eligible for a special enrollment period to sign up for Medicare. If you don’t sign up during this period, you could face penalties and gaps in coverage:

Part A (if you haven’t already enrolled) and Part B. If you’re older than 65 and have been covered by an employer plan, you have up to eight months after the month you leave your job or the month you lose health coverage from your employer (whichever comes first) to sign up. After that, you’re subject to a late-enrollment penalty of up to 10% of your Part B premium for every year you should have been enrolled.

Only health insurance from your current employer is considered primary coverage for the purpose of determining whether you’ve had any gaps. Retiree health insurance, which some employers provide, or coverage under COBRA, the law that allows you to temporarily extend your employer’s benefits, doesn’t count. Give yourself plenty of time, because you’ll need to go to a Social Security office and show that you had creditable coverage from your employer after you turned 65. Ideally, you should start the process a month before you leave your job, says Casey Schwarz, of the Medicare Rights Center.

Medicare Advantage. These plans (also known as Part C) are offered by private insurers that contract with Medicare and pay for some expenses not covered by Medicare. You have 63 days to enroll in a Medicare Advantage plan after your employer-provided coverage ends. For more information about Medicare Advantage plans, go to www.medicare.gov/find-a-plan. If instead of Medicare Advantage you sign up for medigap—supplemental insurance that pays for some expenses Medicare doesn’t cover—you should enroll within six months after you sign up for Part B. Otherwise, you could be charged more or denied medigap insurance altogether because of preexisting health conditions.

Part D. Here, it’s even more important to avoid any gaps in coverage. For every 63 days you go without creditable prescription drug coverage, you’ll pay a penalty equal to 1% of the “national base beneficiary premium” ($35.02 in 2018). That penalty will be added to your Part D premiums for as long as you participate in the program. You can get prescription drug coverage from a stand-alone Part D plan (search for one at medicare.gov) or through a Medicare Advantage plan that provides prescription drug coverage.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Block joined Kiplinger in June 2012 from USA Today, where she was a reporter and personal finance columnist for more than 15 years. Prior to that, she worked for the Akron Beacon-Journal and Dow Jones Newswires. In 1993, she was a Knight-Bagehot fellow in economics and business journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She has a BA in communications from Bethany College in Bethany, W.Va.

-

Dow Loses 821 Points to Open Nvidia Week: Stock Market Today

Dow Loses 821 Points to Open Nvidia Week: Stock Market TodayU.S. stock market indexes reflect global uncertainty about artificial intelligence and Trump administration trade policy.

-

Nvidia Earnings: Live Updates and Commentary February 2026

Nvidia Earnings: Live Updates and Commentary February 2026Nvidia's earnings event is just days away and Wall Street's attention is zeroed in on the AI bellwether's fourth-quarter results.

-

I Thought My Retirement Was Set — Until I Answered These 3 Questions

I Thought My Retirement Was Set — Until I Answered These 3 QuestionsI'm a retirement writer. Three deceptively simple questions helped me focus my retirement and life priorities.

-

10 Retirement Tax Plan Moves to Make Before December 31

10 Retirement Tax Plan Moves to Make Before December 31Retirement Taxes Proactively reviewing your health coverage, RMDs and IRAs can lower retirement taxes in 2025 and 2026. Here’s how.

-

The Rubber Duck Rule of Retirement Tax Planning

The Rubber Duck Rule of Retirement Tax PlanningRetirement Taxes How can you identify gaps and hidden assumptions in your tax plan for retirement? The solution may be stranger than you think.

-

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should Know

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should KnowMedicare Part A and Part B leave gaps in your healthcare coverage. But Medicare Advantage has problems, too.

-

QCD Limit, Rules and How to Lower Your 2026 Taxable Income

QCD Limit, Rules and How to Lower Your 2026 Taxable IncomeTax Breaks A QCD can reduce your tax bill in retirement while meeting charitable giving goals. Here’s how.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits in 2026. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Estate Planning Checklist: 13 Smart Moves

Estate Planning Checklist: 13 Smart Movesretirement Follow this estate planning checklist for you (and your heirs) to hold on to more of your hard-earned money.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.