How "Stealth Tax Hikes" Can Cost You Money Each Year

A 2018 change in the way tax items are adjusted for inflation leads to less tax decreases over time. And some tax items aren't adjusted for inflation at all.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The high inflation numbers from the past 12 months or so are showing up everywhere, from rising rents to soaring food prices. They can also affect how much you'll pay in federal income taxes for 2023. That's because many federal tax items are adjusted each year to account for prior-year inflation, including the income tax brackets, standard deductions, the income levels for figuring whether your long-term capital gains are taxed at 0%, 15% or 20%, and the IRA and 401(k) contribution limits.

These tax items and many other tax credits and deductions will be much higher in 2023 because of high inflation for the period October 1, 2021, through September 30, 2022. But not all tax breaks are adjusted for inflation. And the use of a different inflation standard to adjust tax breaks since 2018 means that the annual adjustments to tax breaks that are adjusted for inflation are smaller than they would have been if the older inflation computation was still used. As a result, taxpayers are starting to see the results of what some call "stealth tax hikes."

[Get a free issue of The Kiplinger Tax Letter, with timely tax advice and guidance to help protect your hard-earned wealth as the tax laws change. No information is required from you to get your free copy.]

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

A Change for Measuring Inflation of Tax Items

Before 2018, the annual inflation adjustment formula for the federal income tax brackets and other tax items was based on the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Some economists had for years argued that the CPI-U tends to overstate actual inflation because the formula doesn't account for how people change their spending patterns as prices rise. These economists claimed that the Chained CPI-U is a better inflation measure.

In 2017, Congressional Republicans were negotiating what was to eventually become former President-Trump's key tax reform law – the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act – and needed some devices to reduce the overall cost of the bill over a 10-year period. One measure they chose was to permanently switch the formula for computing annual inflation adjustments of federal tax items from the CPI-U to the Chained CPI-U, beginning in 2018.

Using the Chained CPI-U results in lower annual inflation adjustments and, thus, smaller annual increases to tax breaks than the regular CPI-U. For example, the increase in the chained CPI-U from October 1, 2021, through September 30, 2022, which is the period used for adjusting tax items for 2023, was 7.83%. On the other hand, the CPI-U rose 8.2% during that same period. This difference might not seem like much for one year; however, the effect is cumulative, with lasting effects that grow bigger over time. That's because, since 2018, the tax items are adjusted each year for inflation at a smaller index rate than that prior to 2018. You can see why some might view this change as a stealth tax hike.

Tax Items That Aren't Inflation-Adjusted

Although many income-tax breaks and income levels are indexed to inflation each year, some important ones are not. Inflation essentially causes the value of these non-adjusted items to diminish. That decrease in value accumulates over time and grows more rapidly in times of rising inflation. That's why some might again refer to these as stealth tax hikes.

Let's look at four of the numerous items that have remained stagnant for years. First, the taxation of Social Security benefits. For decades, the income thresholds at which Social Security benefits start getting taxed have stayed at $32,000 for married couples filing a joint return and $25,000 for single filers. These income thresholds don't go up with inflation, despite the fact that Social Security benefits rise each year and people are generally earning more money than they did in the past. As a result, more cumulative Social Security benefits will be taxed in 2022 than in 2021, in 2023 than in 2022, and so forth.

The maximum home sale tax exclusion is also not adjusted for inflation each year. Many homeowners are aware of the general tax rule for home sales. If you have owned and lived in your main home for at least two out of five years leading up to the sale, up to $250,000 ($500,000 for couples filing a joint tax return) of your gain is tax-free, with any excess taxed at long-term capital gains tax rates. These $250,000 and $500,000 amounts might seem high, but they've never been adjusted for the appreciation in residential real estate during the 25 years this popular tax break has been in effect.

Two Obamacare surtaxes on upper-income individuals aren't adjusted for inflation, either. The 3.8% surtax on net investment income, such as dividends, rents, interest and capital gains, applies to single filers with modified adjusted gross incomes above $200,000 and to joint filers with modified AGIs over $250,000. Modified AGI for this purpose is AGI plus tax-free foreign earned income. The 0.9% surtax on earned income, such as employee wages and self-employment income, kicks in for single filers with earned incomes over $200,000 and for joint filers with earned incomes above $250,000. The $200,000 and $250,000 income thresholds for both of these surtaxes have remained stagnant since the surtaxes first took effect in 2013, despite the growth in wages and incomes over the past decade.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Joy is an experienced CPA and tax attorney with an L.L.M. in Taxation from New York University School of Law. After many years working for big law and accounting firms, Joy saw the light and now puts her education, legal experience and in-depth knowledge of federal tax law to use writing for Kiplinger. She writes and edits The Kiplinger Tax Letter and contributes federal tax and retirement stories to kiplinger.com and Kiplinger’s Retirement Report. Her articles have been picked up by the Washington Post and other media outlets. Joy has also appeared as a tax expert in newspapers, on television and on radio discussing federal tax developments.

-

Timeless Trips for Solo Travelers

Timeless Trips for Solo TravelersHow to find a getaway that suits your style.

-

A Top Vanguard ETF Pick Outperforms on International Strength

A Top Vanguard ETF Pick Outperforms on International StrengthA weakening dollar and lower interest rates lifted international stocks, which was good news for one of our favorite exchange-traded funds.

-

Is There Such a Thing As a Safe Stock? 17 Safe-Enough Ideas

Is There Such a Thing As a Safe Stock? 17 Safe-Enough IdeasNo stock is completely safe, but we can make educated guesses about which ones are likely to provide smooth sailing.

-

3 Smart Ways to Spend Your Retirement Tax Refund

3 Smart Ways to Spend Your Retirement Tax RefundRetirement Taxes With the new "senior bonus" hitting bank accounts this tax season, your retirement refund may be higher than usual. Here's how to reinvest those funds for a financially efficient 2026.

-

5 Retirement Tax Traps to Watch in 2026

5 Retirement Tax Traps to Watch in 2026Retirement Even in retirement, some income sources can unexpectedly raise your federal and state tax bills. Here's how to avoid costly surprises.

-

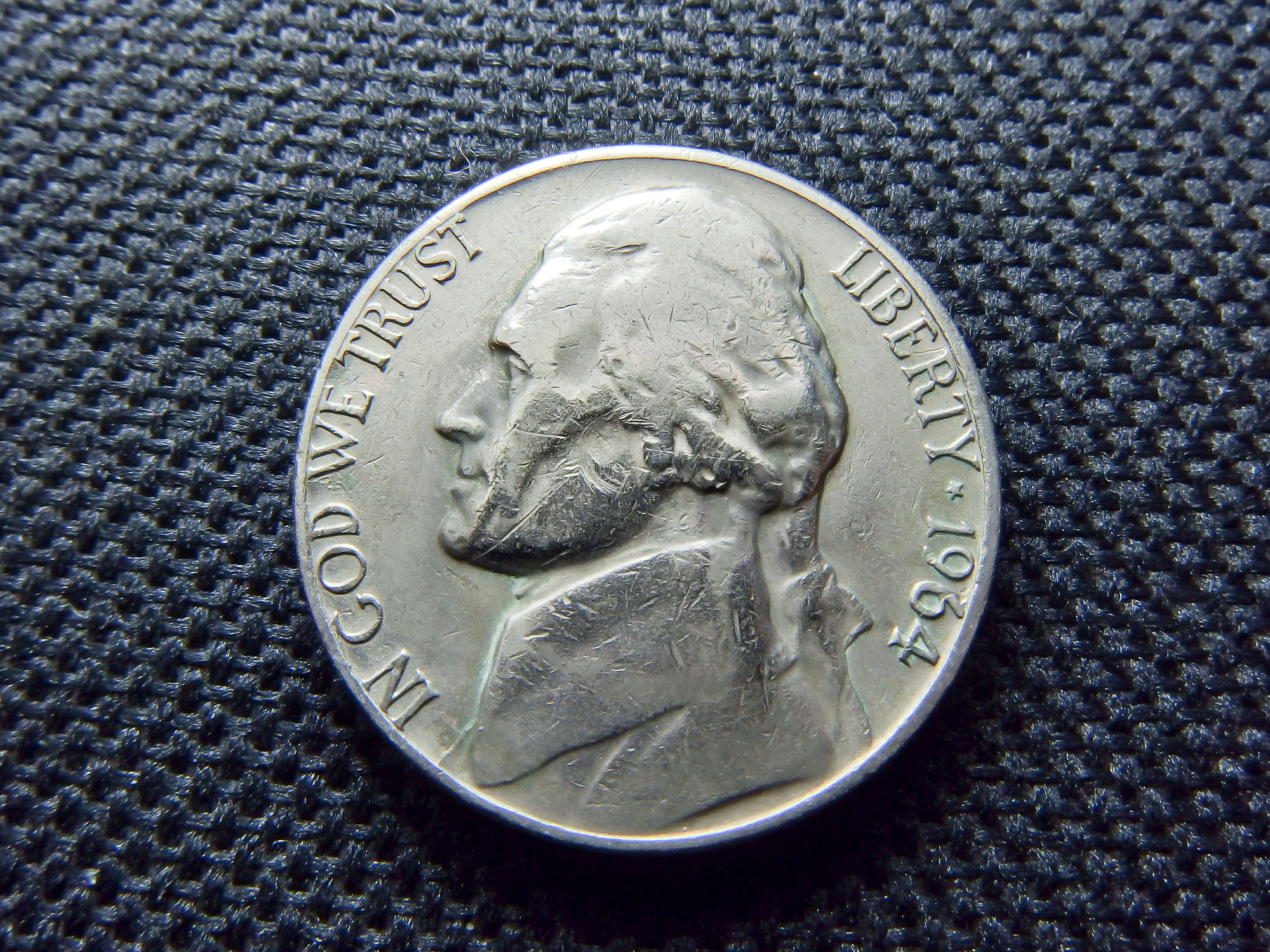

First the Penny, Now the Nickel? The New Math Behind Your Sales Tax and Total

First the Penny, Now the Nickel? The New Math Behind Your Sales Tax and TotalRounding Tax A new era of "Swedish rounding" hits U.S. registers soon. Learn why the nickel might be on the chopping block, and how to save money by choosing the right way to pay.

-

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K Senior Tax Deduction Means for Medicare IRMAA

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K Senior Tax Deduction Means for Medicare IRMAATax Breaks A new tax deduction for people over age 65 has some thinking about Medicare premiums and MAGI strategy.

-

How to Open Your Kid's $1,000 Trump Account

How to Open Your Kid's $1,000 Trump AccountTax Breaks Filing income taxes in 2026? You won't want to miss Form 4547 to claim a $1,000 Trump Account for your child.

-

In Arkansas and Illinois, Groceries Just Got Cheaper, But Not By Much

In Arkansas and Illinois, Groceries Just Got Cheaper, But Not By MuchFood Prices Arkansas and Illinois are the most recent states to repeal sales tax on groceries. Will it really help shoppers with their food bills?

-

7 Bad Tax Habits to Kick Right Now

7 Bad Tax Habits to Kick Right NowTax Tips Ditch these seven common habits to sidestep IRS red flags for a smoother, faster 2026 income tax filing.

-

10 Cheapest Places to Live in Colorado

10 Cheapest Places to Live in ColoradoProperty Tax Looking for a cozy cabin near the slopes? These Colorado counties combine reasonable house prices with the state's lowest property tax bills.