Plan Now for Long-Term Care

You could buy insurance to finance future costs, but policies are pricey. Here’s how to decide whether you need coverage.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

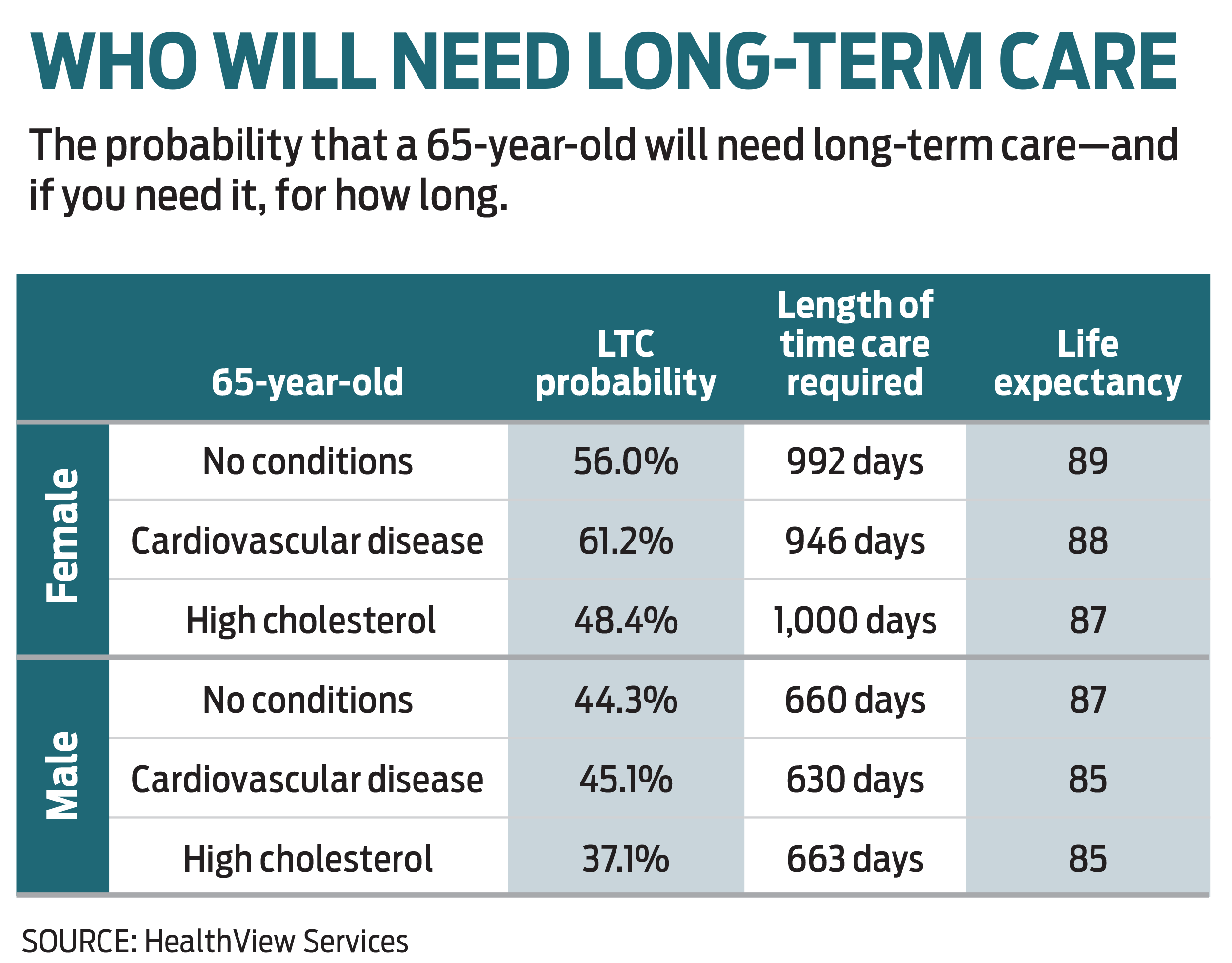

In early June, a 102-year-old South Carolina woman made headlines with her secret to a long life: minding her own business. While most of us probably won’t live that long (or resist the temptation to be nosy), modern medicine has increased the likelihood that we’ll live well into our nineties. But living longer also raises a daunting question: Will you need long-term care, and if so, how will you pay for it?

More than two-thirds of 65-year-olds will need some type of long-term care in their lifetime, according to the Administration for Community Living, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The cost of long-term care can deplete even a well-funded retirement savings plan: According to the 2020 Genworth Cost of Care Survey, the median cost of a private room in a skilled nursing home exceeds $8,800 a month. And the cost varies depending on where you live. A typical private room in New York costs about $12,930 (according to the Genworth survey), compared with about $7,600 in Tennessee. (To get an idea of how much you would need in each state, check the Genworth Cost of Care Survey.)

Many Americans mistakenly believe that Medicare will cover their long-term care. Medicare Part A may cover care that is deemed medically necessary at a certified skilled nursing facility for up to 90 days, but if you need custodial care for a condition such as dementia, Medicare won’t cover the costs.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Long-term-care insurance provides benefits in the event you need help with at least two “activities of daily living”—bathing, getting dressed or eating, for example—for more than 90 days. (Some policies will kick in at 60 days or less, but you’ll pay higher premiums.) Most policies will pay for care in your home or at a long-term-care facility, and some will pay for your transportation to a doctor’s appointment.

A long-term-care policy could give you peace of mind, but the cost is steep. Premiums are expensive and are continuing to increase, due in large part to the rising cost of care and historically low interest rates. These premiums, as well as returns from fixed-income investments, cover the cost of long-term-care insurance. But many policies were designed 30 years ago, when interest rates on U.S. Treasuries were much higher than they are today, says Jesse Slome, executive director of the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance (AALTCI). For a single percentage point decline in interest rates, an insurer needs to raise premiums 10% to 15%, he says. If rates rise significantly, premiums could decrease, but that’s unlikely anytime soon.

Costs aside, you have to deal with the uncertainty of your long-term needs. You or your spouse may not require care at all or only for a short period of time.

Determining whether insurance is right for you depends on whether you have enough money to self-insure and what’s best for your family. If you can’t afford to pay for long-term care, family caregivers could be forced to cut back on work hours or quit their job to take care of you, jeopardizing their own retirement security. In a recent survey by Fidelity Investments, 28% of respondents left their job due to caregiving responsibilities. Of those who eventually went back to work, more than one-third said their earnings declined.

Can you self-insure?

If you have sufficient assets, you may choose to self-insure, which means any long-term-care needs you have will be paid out of your own coffers. “If someone has over $1 million in liquid assets, then they could probably self-insure, provided they were willing to spend it all for their own care,” Slome says. If you’re married, he ups the number to $2.5 million.

When you self-insure, you’re basically betting that you won’t require a prolonged stay in a nursing home—and it’s not a bad bet. According to the Administration for Community Living, most people who go into a nursing home stay for less than 12 months. Instead, you are more likely to rely on in-home care. It costs about $4,600 a month for one or more caregivers to provide 44 hours a week of in-home care, according to the Genworth Study.

Mari Adam, a certified financial planner with Mercer Advisors, in Boca Raton, Fla., suggests sitting down with a financial planner to figure out how much you’ll have in savings to cover long-term care. You’ll typically include funds in your traditional and Roth IRAs, 401(k) plans, taxable accounts, Social Security, and any pension income.

Your home is also part of the equation when calculating whether you can self-insure. If you’ve built a substantial amount of home equity, you can downsize to a smaller place. If you eventually need to move to assisted living or a nursing home, you may be able to use proceeds from the sale of your home to cover the costs. If you don’t want to sell your house, a home-equity line of credit or a reverse mortgage is also an option. (Here's more on how to tap your home equity.)

If you’re enrolled in a high-deductible health insurance plan, you can also harness the tax-saving power of a health savings account (HSA) to pay for some of your long-term-care costs. Contributions are pretax (or deductible if you set up an HSA on your own), earnings are tax-free, and distributions aren’t taxed if you use them to pay for qualified medical expenses. Plus, you can keep your account after you stop working and take tax-free withdrawals for medical expenses in retirement, including any long-term-care costs. To qualify for an HSA, your 2021 health plan must have at least a $1,400 deductible for self-only coverage or $2,800 for family coverage. You can contribute up to $3,600 if you have self-only coverage or up to $7,200 if you have family coverage. If you’re 55 or older at the end of the year, you can contribute an extra $1,000 in catch-up contributions. Once you enroll in Medicare, you’re no longer allowed to contribute to an HSA, but the money continues to grow until you’re ready to use it.

You can also use money from your HSA tax-free to pay long-term-care insurance premiums, with the maximum annual tax-free amount based on your age. If you’re age 40 or younger, you can withdraw up to $450 tax-free from an HSA in 2021 to pay the premiums; if you’re 41 to 50, you can take out $850; if you’re 51 to 60, $1,690; if you’re 61 to 70, $4,520; and if you’re 71 or older, $5,640. If you and your spouse both have long-term-care policies, you can each use money tax-free from your HSA to pay premiums, up to the maximum for each of you based on your ages by the end of the year. These limits increase slightly each year to adjust for inflation.

The case for insurance

Once you have run the numbers, you may conclude that you can handle the cost of long-term care. However, if you’re married, you may still want to consider buying a long-term-care insurance policy, Adam says. The risks are higher that at least one spouse will require long-term care, and those costs could exhaust your combined savings, leaving the other spouse with no resources.

A 55-year-old couple can expect to pay $2,100 a year for a typical policy with an initial benefit pool (the pot of money the insurance company will pay out) for each spouse of $165,000 to cover adult day care, home aide services, assisted living and nursing home costs. If that seems like a high price to pay for something you may never use, there are ways to trim the cost.

Married couples can reduce what they pay in the long run by buying a shared benefit plan, which allows spouses to pool their benefits. If one spouse exhausts his or her benefits, then he or she can tap the other spouse’s share. To get the best value, both spouses need to apply for the same amount of benefits—for example, three years at $200 a day—and then add a shared benefits rider. Plus, depending on the carrier, both spouses can get a discount of between 15% and 30% on their premiums if both buy a policy with the same company, according to Bill Dyess, a long-term-care expert and insurance broker in Boca Raton. However, even if just one spouse buys a policy, the insurance company is likely to provide a 10% to 15% premium discount because married people are less likely to go into a nursing home than single people.

You can also save money by skipping the inflation rider. While these riders will help you keep up with the rising costs of long-term care, they can double your premiums, Dyess says. For example, if a 55-year-old man bought a traditional policy with a benefit pool of $165,000 and he wanted to add a 2% inflation rider, he would pay $1,750 in annual premiums, compared with $950 for a policy without a rider, according to data from the AALTCI. A 55-year-old woman would pay $2,815 instead of $1,500.

Buying a policy when you are in your forties or early fifties will also decrease the cost of premiums (although you’ll be paying for them over a longer period of time). Insurance companies assume you’re at a higher risk for health problems as you age.

Slome says the sweet spot for buying a policy is between the ages of 55 and 65, before you sign up for Medicare. “The first time that people actually take advantage of all those wonderful free health screens is usually after they sign up for Medicare,” he says. “And when they do, the doctors tend to find something.” If you have a health condition, you’ll pay higher premiums, or the insurer may decline to cover you at all.

A traditional policy with $165,000 in initial benefits (and no inflation rider) that would cost a 55-year-old man $950 a year jumps to almost $1,200 a year, on average, if he waits until his 60th birthday to buy coverage. A 55-year-old woman’s premiums would jump from $1,500 to about $2,000.

If you decide to buy a policy at a relatively young age—in your fifties, for example—you may want to add a restoration of benefits rider. If you make a claim and later recover from the illness that caused you to require long-term care, the rider enables the benefit amount you used to be restored to your policy benefit pool. For example, suppose at age 60 you make a claim for $50,000 to pay for your care. If you recover and can show your insurance company you’ve been healthy for a set amount of time (usually determined by the insurance company when the policy is written), the restoration rider will add back the $50,000 you initially used. This type of benefit is typically only good for a one-time use. A policy with this rider, which not every insurer offers, costs about 4% to 6% more than one without it.

If the numbers start to feel overwhelming, keep in mind that you probably don’t need a policy that will cover 100% of your long-term-care costs, Adam says. Instead, you should consider whether a policy can help you pay for some of your long-term care without depleting all of your retirement assets. And if a policy that offers the benefits you want is unaffordable, a long-term-care insurance specialist can help you look for ways to lower the cost.

Consider a hybrid policy

Another alternative to a traditional long-term-care policy is a hybrid life insurance policy that includes long-term-care benefits. If you tap the policy to pay for long-term care, your death benefit will be reduced, although some hybrid policies will pay a small residual benefit even if the entire death benefit is exhausted by long-term-care costs.

Say you have a hybrid policy with a $120,000 death benefit that provides $180,000 of potential long-term-care benefits. If you spend $80,000 on long-term care, your heirs will still receive $40,000 after you die. If you spend the entire $180,000 on care and your policy pays a small residual death benefit, your beneficiaries may receive $10,000.

Such a policy may appeal to you if you’re determined to leave something to your heirs, but you’ll pay more for this kind of insurance. A 55-year-old man can expect to pay roughly $4,600 a year (compared with $950 for a traditional long-term-care insurance policy) for a life insurance policy that provides $180,000 in long-term-care benefits with a $120,000 death benefit.

To find a long-term-care specialist, go to aaltci.org and click on “LTC Resources.” Type in your zip code to find a professional in your area; make sure he or she has a “certified in long-term care” designation.

Is government help on the way?

In a recent poll conducted by the Associated Press, 60% of respondents favored a federal, Medicare-like long-term-care insurance program. Some 70% said Medicare should cover long-term care. While a federal long-term-care program is unlikely anytime soon, President Joe Biden has proposed spending $400 billion on home and community-based services for long-term care (although the outlook for the proposal is unclear).

In the meantime, some states may look into starting their own programs. In 2019, the Washington State legislature passed a bill to create a state long-term-care program funded by a new payroll tax. Starting on January 1, 2022, the state will add an additional 58 cents to payroll taxes for every $100 of eligible wages reported on Form W-2. Employees can opt out by November 1, 2021, if they purchase a qualifying long-term-care insurance policy.

If you’re thinking that Medicaid will be your golden ticket for long-term care, think again. To qualify for Medicaid, you must spend down nearly all of your assets first. Medicaid also has a “look back” period that involves examining your financial transactions from the past five years to determine whether you gave away money to qualify for Medicaid, which could render you ineligible. And even if you qualify for Medicaid, you’ll have to go to a facility that accepts Medicaid, and as the population ages, those will be increasingly hard to find.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Rivan joined Kiplinger on Leap Day 2016 as a reporter for Kiplinger's Personal Finance magazine. A Michigan native, she graduated from the University of Michigan in 2014 and from there freelanced as a local copy editor and proofreader, and served as a research assistant to a local Detroit journalist. Her work has been featured in the Ann Arbor Observer and Sage Business Researcher. She is currently assistant editor, personal finance at The Washington Post.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Maximize Your Social Security Check?

Quiz: Do You Know How to Maximize Your Social Security Check?Quiz Test your knowledge of Social Security delayed retirement credits with our quick quiz.

-

Will You Get a Trump Tariff Refund in 2026? What to Know Now

Will You Get a Trump Tariff Refund in 2026? What to Know NowTax Law The Supreme Court's tariff ruling has many wondering about refund rights and how tariff refunds would work.

-

2026 Tax Refund Delays: 5 States Where Your Money Is Stuck

2026 Tax Refund Delays: 5 States Where Your Money Is StuckState Tax From New York to Oregon, your state income tax refund could be delayed for weeks. Here's what to know.

-

I Tried a New AI Tool to Answer One of the Hardest Retirement Questions We All Face

I Tried a New AI Tool to Answer One of the Hardest Retirement Questions We All FaceAs a veteran financial journalist, I tried the free AI-powered platform, Waterlily. Here's how it provided fresh insights into my retirement plan — and might help you.

-

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should Know

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should KnowMedicare Part A and Part B leave gaps in your healthcare coverage. But Medicare Advantage has problems, too.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits in 2026. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.

-

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026SEP IRA A good option for small business owners, SEP IRAs allow individual annual contributions of as much as $70,000 in 2025, and up to $72,000 in 2026.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026simple IRA For 2026, the SIMPLE IRA contribution limit rises to $17,000, with a $4,000 catch-up for those 50 and over, totaling $21,000.