Fintech: The Bank Disrupters

Fintechs offer mostly free accounts with tantalizing yields and slick features, but don’t expect much hand-holding.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

With the invention of the smartphone and the ascendancy of app-based services, financial technology companies—better known as fintechs—have been disrupting traditional banking, offering attractive features to new customers who aren’t tied to traditional banks. These challenger banks (or neobanks, as they’re sometimes called) tout higher rates, quicker access to paychecks, real-time spending data and, for the most part, coverage by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.—all while charging low (or no) fees and being mobile-centric.

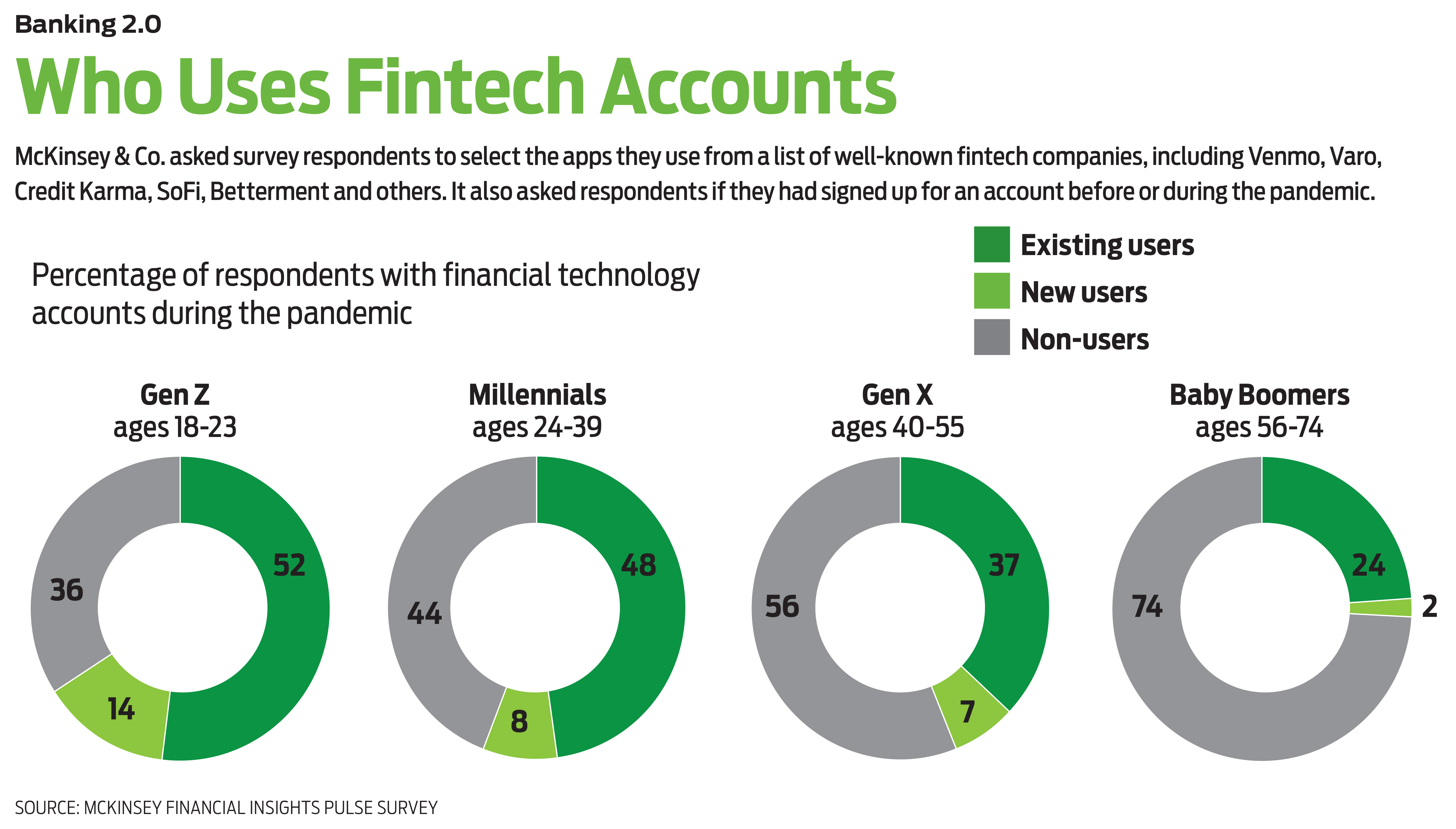

Consumers are taking notice, especially since COVID-19 made banking at a physical branch more difficult. In a December survey from consulting firm McKinsey & Co., 36% of respondents who were thinking about opening a fintech account said that these accounts were easier to use than a traditional bank account. Fintechs tend to target younger consumers, who may not have a loyal banking relationship, and other demographics that the companies believe are not well served by traditional banks.

For example, challenger bank First Boulevard is directly targeting Black consumers with an account that will offer 15% cash back on purchases from Black-owned businesses that participate in its rewards network, as well as automated savings via a purchase round-up feature and early payday access. There are no overdraft or account-maintenance fees, nor is a minimum balance required. Greenwood Bank, which targets Black and Latino consumers, has similar offerings. Currently, both fintechs require you to get on a waiting list before you gain access. Targeting people in the lesbian, gay, queer and transgender communities, Daylight allows customers to choose the name they want displayed on their debit card and have access to an assigned financial coach. Daylight charges no monthly fees.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

But while the conventional wisdom is that almost all fintech users are members of Generation Z or millennials, older customers are getting in on the action, too. According to the McKinsey survey, 26% of baby boomers and 44% of Gen Xers have some type of fintech account.

Before you decide to leave your traditional bank for something more hip or sleek, see whether the features of a challenger bank you’re interested in meet your needs.

How they work

Traditional banks can’t operate without a bank charter. Under a charter, banks agree to federal oversight to keep accounts safe, insured and accessible. Fintechs currently don’t operate under such rules, mostly because keeping up with ever-changing regulations is expensive and slows their ability to bring a new product to market.

To get around the regulatory issue, fintechs “rent” the compliance or regulatory function of a bank. In return, the bank gains access to the fintech’s technology, helping the bank become more digitally focused without needing to buy a technology company or build its own app or online interface. From there, the fintech is allowed to accept deposits, and funds are held at the FDIC-insured bank.

“It’s not big banks like J.P. Morgan or Citibank that are taking part in these partnerships, but smaller, regional banks that may not have the money to spend to directly compete with fintechs or even bigger banks,” says Drew Pascarella, founder of Cornell’s FinTech Intensive academic program. For example, Dallas-area MapleMark Bank recently announced a new partnership with Raisin, a German fintech specializing in certificates of deposit. As Raisin’s first U.S. bank partner, MapleMark has given Raisin access to the American market. With Raisin’s technology, the bank can offer three different CD options, including a CD ladder, to its customers while marketing its offerings to new customers as well.

Some fintechs have applied for and received their own bank charters. The first to do so was Varo Money, which launched in 2017. It received regulatory approval in July 2020 to relaunch as Varo Bank, after which it invited former Varo Money customers to open accounts at Varo Bank and move their funds.

SoFi, which pioneered student loan refinancing and now offers an interest-bearing checking account and other products, is hoping to do the same. The company received preliminary approval from regulators in October but is now working on buying a community bank to secure a charter.

Fintechs can also decide to go it alone. The drawback is that if a fintech doesn’t partner with a bank, the account isn’t covered by FDIC insurance. Currently, some fintechs specializing in cryptocurrency operate this way, says Ken Tumin, founder of DepositAccounts.com, a deposit account comparison website. BlockFi, for example, offers an interest-bearing cryptocurrency account in which you can earn up to 7.5%, depending on the type of cryptocurrency deposited.

Caveat depositor

The biggest benefit fintechs offer is their variety of free or mostly free features—typically with no overdraft fees. (Big financial institutions charge, on average, a little over $33 when you overdraw your account. In 2020, banks made an estimated $31.3 billion in overdraft revenue.) To attract customers, fintechs including Chime, Varo Bank, Current, Dave and a slew of others market their no-overdraft-fee policy, and some allow you to access your paycheck in advance.

On the other hand, customer service is a low priority. If you have a question or complaint, you typically have to communicate via e-mail or live chat on a website. You may never be able to talk with a human on the phone. (For a look at how Chime’s policies turned into a customer service black eye, see below.)

Another concern: Free can’t last forever. The potential for fintechs to add overdraft fees down the road is giving consumer advocates pause. Plus, as these companies begin to offer more-sophisticated product lineups, the costs will eventually rise.

“Right now, these fintechs are choosing to eat the cost on these features to gain customers,” says Eric Solis, CEO of MovoCash, a financial technology company that offers on-demand mobile banking and other services in one app. “But fee creep is coming. The costs are the bottom of the iceberg that consumers don’t see, and you can only eat that cost for so long,” he says.

Users of the savings deposit app Digit are already experiencing this fee creep. Digit initiated a monthly fee of $2.99 in 2017. That was pushed up to $5, and starting this fall the fee will be $9.99 a month. That’s when Digit will debut new features, including a checking account called Digit Direct, which employs artificial intelligence to help customers budget, save and invest. Customers will also have access to 55,000 fee-free ATMs. Current Digit users who upgrade to Direct will continue to pay the $5 monthly fee for six months before the $9.99 fee kicks in. Those who don’t want to use the new banking feature can choose not to upgrade and continue using the $5-a-month version of the app. (New customers interested in Direct have to join its waiting list.)

Along with fee creep, some fintechs could chip away at their high yields, or you may have to jump through hoops to get them. T-Mobile customers who sign up for T-Mobile Money, a checking account provided by BankMobile, can earn up to 4% on balances up to $3,000 (1% on higher balances). But to get the initial 4%, you have to be enrolled in a qualifying wireless plan, register for perks with your T-Mobile ID and make 10 qualifying purchases with your T-Mobile Money debit card each month.

A few fintechs have entered into partnerships with sweep account services as an entrée into the U.S. banking system. With this setup, the fintech works with a network of banks instead of one, “sweeping” deposits into multiple FDIC-insured banks. This arrangement, however, is more convoluted, and it poses more risks for consumers because they’re not made aware of which bank has their deposits and could have trouble accessing their money, says Tumin.

That’s what happened to Beam Financial customers last year. Instead of receiving transfers out of their Beam accounts within the promised three- to five-day window, some customers waited weeks or months. Customer service requests made through the mobile app went unanswered. And because Beam partnered with a sweep network, customers did not know which bank had their money. In response to these complaints and others, the Federal Trade Commission sued Beam. In March 2021, the company settled with the Federal Trade Commission to refund customers all funds, including interest, and Beam can no longer accept deposits.

If you’re simply looking for a better yield on your savings, take a look at internet banks. Go to www.depositaccounts.com and select “Personal Savings Accounts” under the Savings Accounts navigation tab.

Chime strikes a sour note

As Americans received stimulus money, unemployment checks and tax refunds, Chime ran an aggressive marketing campaign inviting new customers to sign up for accounts. But as the money rolled in, Chime began closing some accounts. When the customers with frozen funds e-mailed Chime to ask why, they received responses noting that the deposits had been flagged as “unusual activity,” according to a report from ProPublica, a nonprofit investigative publication.

Chime requested that these customers send in identification and proof that the stimulus checks and unemployment checks were legitimate. Yet some customers had to wait months to gain access to their money, ProPublica reports. (At press time, Chime had not yet responded to our request for comment.) Chime noted (as reported by ProPublica) that the company, along with its partner banks Bancorp and Stride, was aware of increased scam activity spurred by the various stimulus packages and that the accounts were suspended as part of its fraud-prevention methods.

“A lot of people out there are trying to get a U.S. bank account for the wrong reasons, so there are valid reasons for vetting accounts and vetting payments,” says Adam Rust, senior policy adviser at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, a national membership group that champions fairness in lending, housing and wealth-building. “But it sounds as if Chime was advertising for this stimulus use, so it certainly raises questions about its preparation.”

The situation highlights the need to ask a neobank how it will resolve any issues that arise. Will problems be handled only via chatbot or e-mail? And do you know exactly where your money resides? For example, is your name on an account at a partner bank? With a traditional bank, you can typically reach a customer service rep via phone or visit a branch, cutting out any middlemen. Whether you set up an account with a neobank or stick with a traditional institution, report any problems you have to the institution as well as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (go to www.consumerfinance.gov/complaint).

Find the best fintech account for you

If you’re comfortable with all-digital banking, fintechs can be an attractive alternative to a traditional bank. “Savers might be attracted to some of the high-yield accounts offered by fintechs,” says Adam Rust, senior policy adviser at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, a national membership group that champions fairness in lending, housing and wealth-building. “Yields were sometimes above 2% as recently as a year ago and are still above what is available at the typical bank,” he adds.

Varo Bank offers a savings account that earns up 3%. To get the full rate, you must receive a monthly total of $1,000 in direct deposits into either the savings account or the Varo Bank checking account. Neither your checking nor your savings account balance can dip below $0 for the month, and your savings account can’t exceed a daily balance of $5,000 for any day of the month. To apply, download the Varo Bank app from the Apple App Store or the Google Play Store.

On top of providing VantageScores, credit monitoring and tax-prep services, Credit Karma is also getting into the fintech game. The company now offers a spending and savings account under Credit Karma Money. The spending account is free to open, and there’s no minimum balance to maintain. If you set up a direct deposit into the spending account, you can access your paycheck up to two days early. Plus, there are no overdraft fees, and users can access more than 55,000 ATMs. Bonus: Credit Karma may reimburse you for a purchase thanks to its Instant Karma program. The savings account earns 0.17%.

If you’re more concerned about collecting rewards, the free basic checking account from Current is worth a look. The account has no overdraft fees, no monthly maintenance fee and no minimum-balance requirement. It also offers mobile check deposit and access to 55,000 free ATMs. To earn rewards points, you activate offers from participating retailers within the app. Current users who want early paycheck access can upgrade to a premium account for $4.99 a month.

Fintech is also addressing the specific needs of gig workers. Lili, for example, offers a checking account with tax-planning tools (in addition to charging no overdraft fees and requiring no minimum balance). Gig workers can track and sort expenses into “life” and “work” categories to generate an expense report when it’s time to pony up taxes to Uncle Sam. The app also lets you automatically save a portion of each gig payment in a tax bucket.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Rivan joined Kiplinger on Leap Day 2016 as a reporter for Kiplinger's Personal Finance magazine. A Michigan native, she graduated from the University of Michigan in 2014 and from there freelanced as a local copy editor and proofreader, and served as a research assistant to a local Detroit journalist. Her work has been featured in the Ann Arbor Observer and Sage Business Researcher. She is currently assistant editor, personal finance at The Washington Post.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Maximize Your Social Security Check?

Quiz: Do You Know How to Maximize Your Social Security Check?Quiz Test your knowledge of Social Security delayed retirement credits with our quick quiz.

-

Will You Get a Trump Tariff Refund in 2026? What to Know Now

Will You Get a Trump Tariff Refund in 2026? What to Know NowTax Law The Supreme Court's tariff ruling has many wondering about refund rights and how tariff refunds would work.

-

2026 Tax Refund Delays: 5 States Where Your Money Is Stuck

2026 Tax Refund Delays: 5 States Where Your Money Is StuckState Tax From New York to Oregon, your state income tax refund could be delayed for weeks. Here's what to know.

-

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't Need

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't NeedFinancial Planning If you're paying for these types of insurance, you might be wasting your money. Here's what you need to know.

-

Money for Your Kids? Three Ways Trump's ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ Impacts Your Child's Finances

Money for Your Kids? Three Ways Trump's ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ Impacts Your Child's FinancesTax Tips The Trump tax bill could help your child with future education and homebuying costs. Here’s how.

-

Key 2025 Tax Changes for Parents in Trump's Megabill

Key 2025 Tax Changes for Parents in Trump's MegabillTax Changes Are you a parent? The so-called ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ (OBBB) impacts several key tax incentives that can affect your family this year and beyond.

-

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online Bargains

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online BargainsFeature Amazon Resale products may have some imperfections, but that often leads to wildly discounted prices.

-

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should Know

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should KnowMedicare Part A and Part B leave gaps in your healthcare coverage. But Medicare Advantage has problems, too.

-

QCD Limit, Rules and How to Lower Your 2026 Taxable Income

QCD Limit, Rules and How to Lower Your 2026 Taxable IncomeTax Breaks A QCD can reduce your tax bill in retirement while meeting charitable giving goals. Here’s how.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnb

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnbreal estate Here's what you should know before listing your home on Airbnb.