When to Give Up on a Stock

Selling should have little to do with price. What matters is the business itself and whether it has changed for the worse.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Buying stocks is much easier than selling them. When you decide to purchase shares, you usually act with enthusiasm.

But selling is drenched in ambivalence. Many investors just aren’t sure whether it’s the right time. The psychology can be perverse. Selling a stock in March at a 40% profit and then watching the price double by September can feel worse than selling it and watching the company go bankrupt – even though in both cases, your gain is the same.

The ones that got away hurt the most. I bought Netflix (NFLX, $510) shortly after its 2002 initial public offering. I liked the idea of circumventing video stores and believed that someday the company would figure out how to send me movies online. I sold out with what Peter Lynch called a three-bagger – a tripling in price. By December 2020, Netflix had become a 470-bagger for those who bought the IPO.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Although I continue to like the company, I can’t bring myself to buy the stock back. (Stocks and funds I like are in bold; prices are as of January 8.)

Many investors fall prey to the psychology of anchoring. If they buy a stock for $50 a share and it falls sharply, their strategy is to wait until the stock gets back to the anchor price of $50 before selling – even if they no longer like the company. Why not take the remaining proceeds and make a better investment? This misguided approach to selling is also driven by loss aversion: the idea, proven by researchers, that people would rather avoid a $1,000 loss than score a $1,000 gain.

Then there’s the desire to prevent regret. One of America’s most successful private-equity managers once told me that when he sold a stock, he took “schmuck insurance.” He always tried to maintain a small interest in the company he was selling, just in case it soared in value afterward and he looked like a fool or a jerk – a schmuck, in other words – for exiting too soon.

Buy and Hold ... And Hold

The simple antidote to being captured by the perverse psychology of selling is never to sell at all. As Warren Buffett wrote, “Inactivity strikes us as intelligent behavior.”

History shows that, for long-term investors, not selling is a profitable strategy. From 1973 through 2020, the worst rolling 20-year period (that is, January 1, 1973, to December 31, 1992; February 1, 1973, to January 31, 1992; and so on) for the S&P 500 still produced an annual average gain of 4.8% – a lot more than long-term bonds yield these days. Also, if you don’t sell, you have to make only one decision (to buy) rather than three (to buy, to sell and to buy something else). And, not selling lets you postpone capital gains taxes.

My own view is that although you should hope your stock purchase is a forever investment, you should be aware that selling is sometimes intelligent behavior. But when to sell? The late investment guru Philip A. Fisher, author of the 1957 classic Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits, focused on a company’s performance and prospects. He wrote that you should sell if there has been “a deterioration of management, or the company no longer has the prospect of increasing the markets for its products as it formerly did.”

Fisher’s concern was not the state of the economy or the actions of the Federal Reserve. What mattered to him was the business itself and whether it had changed for the worse. I will add that you cannot identify that change unless you can articulate the reason you bought the company in the first place. In other words, you can’t know when to sell unless you know why you bought.

For example, I recommended (and later bought) Lululemon Athletica (LULU, $365) after its founder, Chip Wilson, a brilliant leader who had too limited a vision, resigned as chairman, and the company’s new CEO broadened the appeal of the product line and vastly increased internet sales. Since I made Lululemon my personal choice among the 10 stocks I recommended for 2018, the price has more than quintupled. Why would I sell? If new management decided to revert to Wilson’s yoga-fixated approach, if the brand tried to become all things to all people, or if fierce new competition developed.

I recommended New York Times (NYT, $48) stock on the 2019 list when it appeared the company had figured out a way to supplant lost ad revenues with online subscription dollars. The stock has nearly doubled. For now, the company has few peers as a source of sophisticated news, features and analysis. Perhaps more competitors will spring up or Times management will enter into less-worthy businesses, such as theme parks. Then, I would advise selling.

Like Fisher’s selling strategy, mine has little in common with the one that motivates most investors. They sell because of price: Either a stock has gone up and they want to take profits, or it has gone down and they want to avoid more losses.

It is true there are sometimes good reasons to cash in your chips. You may have a better use for the money – another investment, perhaps, or paying for your child’s education. But setting a price goal often means sacrificing huge gains. Yes, a declining price could be a signal that something is seriously wrong with the company. Examine the business for defects, as Fisher advises. If you are still passionate about it, then price declines are opportunities to buy more.

Call in the Pros

A business-centric selling strategy is not easy to follow. It requires time and a temperament for research. A good substitute is owning index funds, letting index compilers like S&P weed out deteriorating companies, and then never selling.

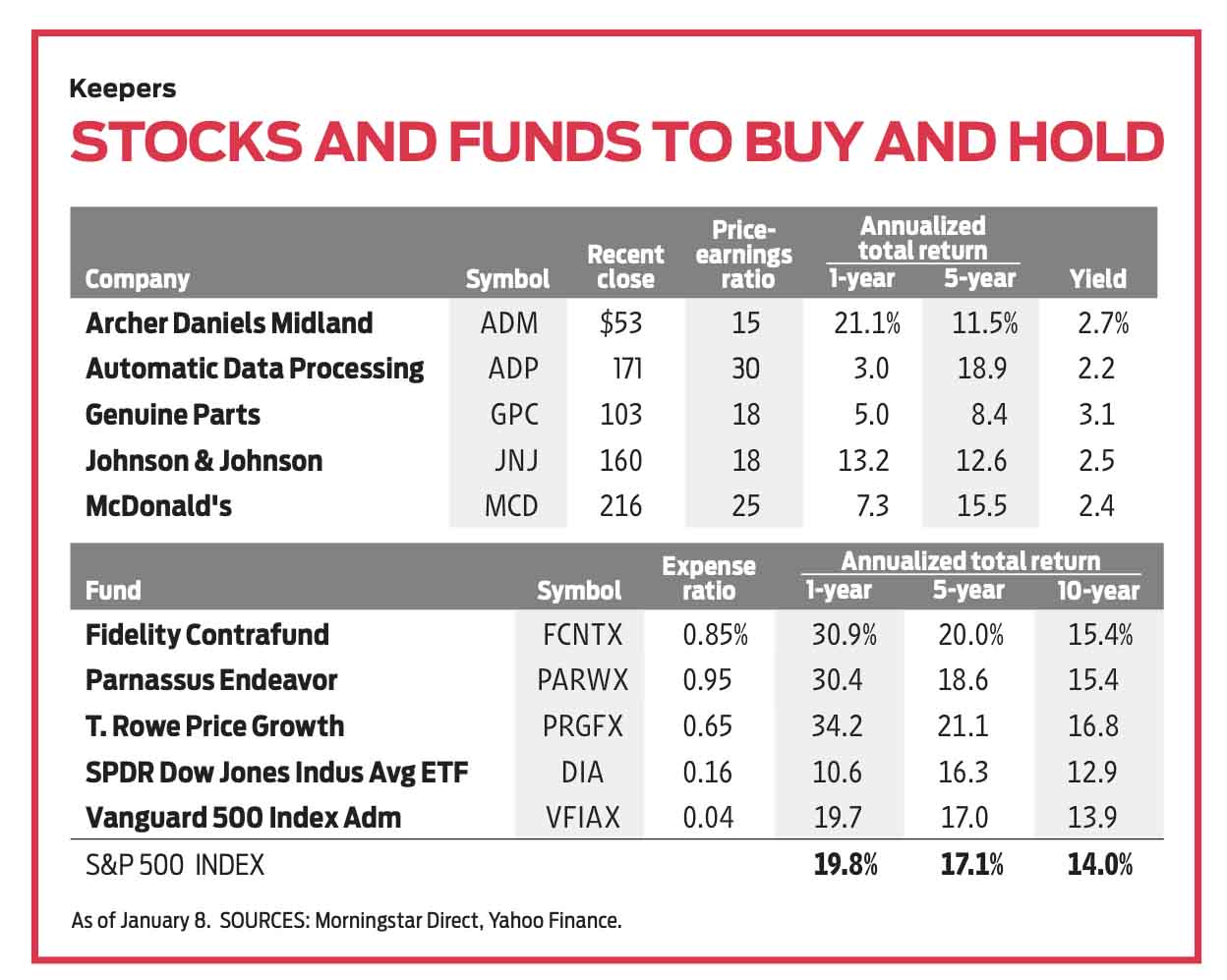

For this reason and because of their low expense ratios, I am always fond of index funds such as Vanguard 500 Index Admiral (VFIAX), which charges 0.04%, and exchange-traded funds including SPDR Dow Jones Industrial Average (DIA), or “Diamonds,” with expenses of 0.16%.

Established managed mutual funds that own large-cap stocks and have relatively low turnover represent another excellent approach. My favorites include Fidelity Contrafund (FCNTX), which has returned an annual average of 15.4% over the past 10 years; T. Rowe Price Growth (PRGFX), launched 71 years ago and returning 16.8% annually over the past decade; and Parnassus Endeavor (PARWX), returning 15.4%. (Note: Parnassus founder Jerome Dodson is no longer managing Endeavor, but I expect his successor, Billy Hwan, to continue the successful run.)

Another good way to avoid the pain of selling is a strategy I like to call faith-based investing. Own long-running businesses with powerful brand names and solid markets that perform well through thick and thin. Many such companies consistently raise their dividends.

For example, Johnson & Johnson (JNJ, $160), with a portfolio of pharmaceuticals, consumer health products such as Tylenol, and medical devices, increased its quarterly payout in 2020 for the 58th consecutive year. The stock currently yields 2.5%. Companies that have raised dividends for more than 40 straight years include Archer Daniels Midland (ADM, $53), an agricultural products and services company, yielding 2.7%; McDonald’s (MCD, $216), by far the most profitable restaurant chain, 2.4%; Automatic Data Processing (ADP, $171), employer services, 2.2%; and Genuine Parts (GPC, $103), vehicle products, 3.1%.

Buying and holding should be your default position. But if you believe you need to sell, try to summon at least as much conviction as when you bought.

James K. Glassman chairs Glassman Advisory, a public-affairs consulting firm. He does not write about his clients. His most recent book is Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments in a Time of Turbulence. Of the securities mentioned in this column, he owns Lululemon Athletica, New York Times and Diamonds.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K 'Senior Deduction' Means for Medicare IRMAA Costs

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K 'Senior Deduction' Means for Medicare IRMAA CostsTax Breaks A new deduction for people over age 65 has some thinking about Medicare premiums and MAGI strategy.

-

U.S. Congress to End Emergency Tax Bill Over $6,000 Senior Deduction and Tip, Overtime Tax Breaks in D.C.

U.S. Congress to End Emergency Tax Bill Over $6,000 Senior Deduction and Tip, Overtime Tax Breaks in D.C.Tax Law Here's how taxpayers can amend their already-filed income tax returns amid a potentially looming legal battle on Capitol Hill.

-

5 Investing Rules You Can Steal From Millennials

5 Investing Rules You Can Steal From MillennialsMillennials are reshaping the investing landscape. See how the tech-savvy generation is approaching capital markets – and the strategies you can take from them.

-

The Most Tax-Friendly States for Investing in 2025 (Hint: There Are Two)

The Most Tax-Friendly States for Investing in 2025 (Hint: There Are Two)State Taxes Living in one of these places could lower your 2025 investment taxes — especially if you invest in real estate.

-

Bond Basics: Zero-Coupon Bonds

Bond Basics: Zero-Coupon Bondsinvesting These investments are attractive only to a select few. Find out if they're right for you.

-

Bond Basics: How to Reduce the Risks

Bond Basics: How to Reduce the Risksinvesting Bonds have risks you won't find in other types of investments. Find out how to spot risky bonds and how to avoid them.

-

What's the Difference Between a Bond's Price and Value?

What's the Difference Between a Bond's Price and Value?bonds Bonds are complex. Learning about how to trade them is as important as why to trade them.

-

Bond Basics: U.S. Agency Bonds

Bond Basics: U.S. Agency Bondsinvesting These investments are close enough to government bonds in terms of safety, but make sure you're aware of the risks.

-

Bond Ratings and What They Mean

Bond Ratings and What They Meaninvesting Bond ratings measure the creditworthiness of your bond issuer. Understanding bond ratings can help you limit your risk and maximize your yield.

-

Bond Basics: U.S. Savings Bonds

Bond Basics: U.S. Savings Bondsinvesting U.S. savings bonds are a tax-advantaged way to save for higher education.

-

Bond Basics: Treasuries

Bond Basics: Treasuriesinvesting Understand the different types of U.S. treasuries and how they work.