The 20 Biggest Wealth Destroyers of the Past 30 Years

Lehman Brothers and Enron are notorious for destroying shareholder wealth, but they can't compete with these 20 names.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

When folks think of the worst stocks of the past 30 years, Lehman Brothers, Enron or Arthur Andersen are but three among legions of notorious names that might immediately come to mind.

Yet somehow, those corporate catastrophes don't come near cracking the top 20 stocks that destroyed the most shareholder wealth in recent history.

That's partly due to the depressing fact that there's simply too much competition.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

The respective popping of the tech and real estate bubbles in the U.S. and Japan; an appalling catalog of corporate malfeasance, malpractice and fraud; and the Great Financial Crisis make for a crowded field when it comes to the wholesale destruction of shareholder wealth since 1990.

But before we get to these all-time drags on shareholder performance, let's start by defining our terms for wealth creation and destruction.

What Is "Wealth Destruction"?

Hendrik Bessembinder, a finance professor at Arizona State University's W.P Carey School of Business, takes a different tack when it comes to studying the best and worst performing equities.

The idea isn't to figure out stocks' straight-up returns, be they positive or negative, over some defined time period. Rather, as Dr. Bessembinder writes in his research:

"We measure for each stock the dollar amount by which the wealth of shareholders in aggregate was enhanced by their decision to take on the risk of stock investing rather than investing in low risk U.S. Treasury bills."

Put another way, Bessembinder measures long-term shareholder outcomes both in terms of compound returns and relative improvement to shareholders' wealth.

To oversimplify a bit: Imagine an investor back in 1990. Rather than buy shares in, say, Apple (AAPL), what if he or she instead sunk their capital into risk-free one-month U.S. Treasury bills?

Think of Apple's "return" in this case as essentially the change in market capitalization adjusted for things such as dividends, share repurchases or new equity issuance, when compared against the compound return of risk-free one-month U.S. Treasury bills over the same time period.

The T-bills are a kind of stand-in for opportunity cost. And the difference over time between the two investment choices, when positive, is wealth creation. It's the enhancement.

In Apple's case, the enhancement happens to be tops among the 30 best stocks of the past 30 years. Apple created $2.67 trillion in shareholder wealth, or 23.5% annualized, from 1990 to 2020, according to Bessembinder's research.

But what happens when the enhancement is negative? That's when you get wealth destruction.

"Wealth destruction is not simply a decline in market cap, though in many instances this will be the largest contributor," Bessembinder says. "My calculations all take the one-month Treasury bill rate as the opportunity cost."

A firm that generated a zero return would be destroying wealth, at least in those months where T-bill rates are positive, Bessembinder adds. His calculations also implicitly account for any share repurchases or new equity issuances.

"If a firm's market capitalization falls, but the reason is a share repurchase, then no wealth is destroyed," Bessembinder says.

The 20 Biggest Wealth Destroyers of the Past 30 Years

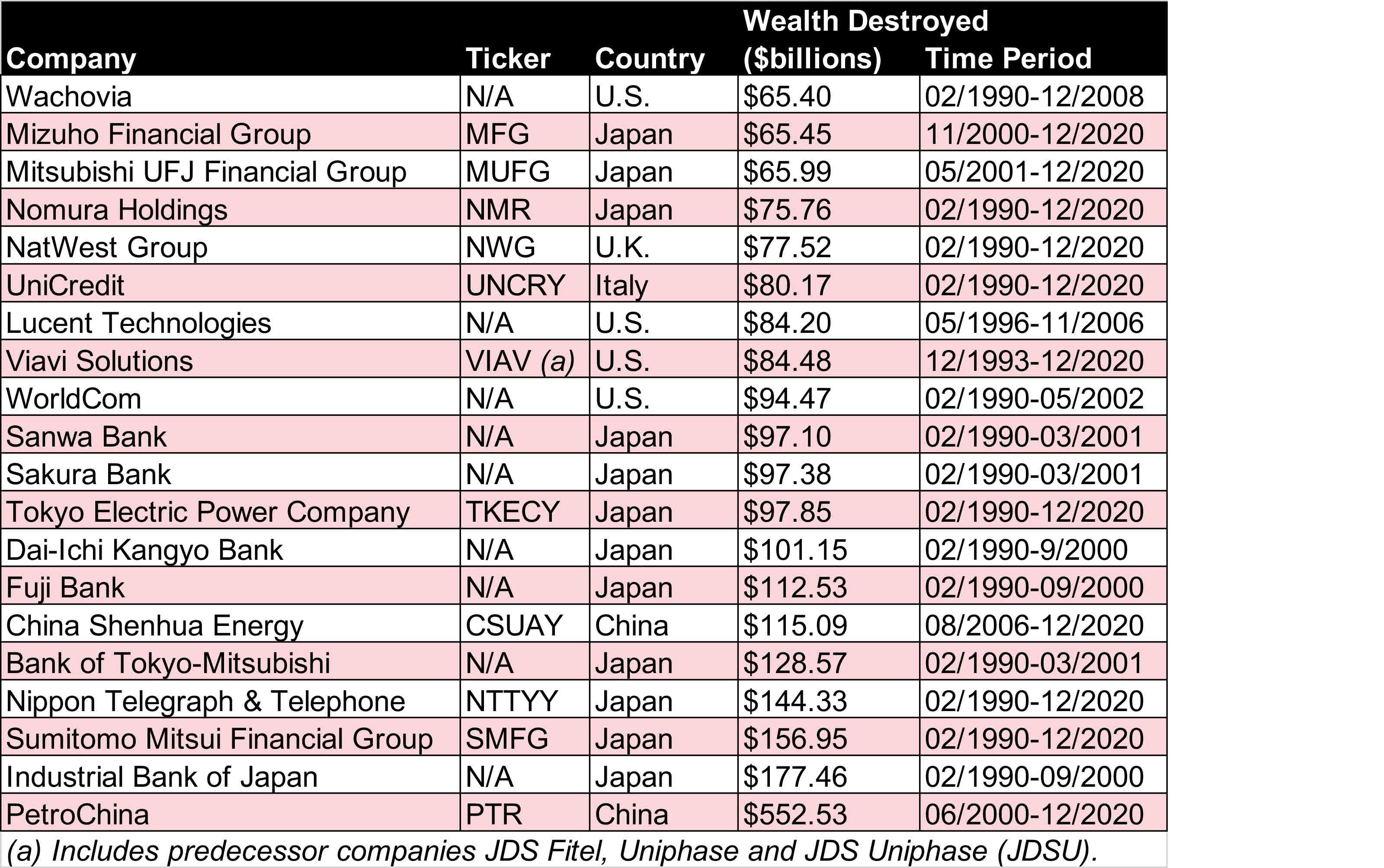

Have a look at the top 20 stocks of the past 30 years in terms of how much shareholder wealth they destroyed:

Note that 12 of the wealth destroyers in the table above are Japanese firms – and 10 of those names are banks. Japan's banking crisis, which ran from 1991 to 2005 following a collapse in stock, real estate and other asset prices, is to blame.

The U.S. has the dubious distinction of making four contributions to the list. Wachovia, which fell apart amid the GFC, is today part of Wells Fargo (WFC). WorldCom, among the most infamous accounting scandals of its day, emerged from bankruptcy in 2003 under the name MCI. Parts of that business survive today within Verizon's (VZ) Verizon Business division.

However, the greatest wealth destroyer of the past three decades by far is PetroChina (PTR). The Chinese oil-and-gas company is the listed arm of state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation. From June 2000 through December 2020, its Shanghai- and Hong Kong-listed shares destroyed more than a half-trillion U.S. dollars in shareholder wealth, Bessembinder found.

The Takeaway for Investors

Perhaps the most salient aspect of Bessembinder's research is that the vast majority of stocks are duds. Indeed, all of the $76 trillion in net global stock market wealth created over the past 30 years was generated solely by the top-performing 2.4% of stocks.

Investors were highly unlikely to buy and hold a concentrated portfolio of the market's vanishingly small handful of outsized wealth creators. At the same time, the market's biggest wealth destroyers were out there helping to crush investors' long-term plans and goals.

If the lists of greatest wealth creators and wealth destroyers tell us anything, it's the supreme importance of having a diversified portfolio.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Dan Burrows is Kiplinger's senior investing writer, having joined the publication full time in 2016.

A long-time financial journalist, Dan is a veteran of MarketWatch, CBS MoneyWatch, SmartMoney, InvestorPlace, DailyFinance and other tier 1 national publications. He has written for The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg and Consumer Reports and his stories have appeared in the New York Daily News, the San Jose Mercury News and Investor's Business Daily, among many other outlets. As a senior writer at AOL's DailyFinance, Dan reported market news from the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

Once upon a time – before his days as a financial reporter and assistant financial editor at legendary fashion trade paper Women's Wear Daily – Dan worked for Spy magazine, scribbled away at Time Inc. and contributed to Maxim magazine back when lad mags were a thing. He's also written for Esquire magazine's Dubious Achievements Awards.

In his current role at Kiplinger, Dan writes about markets and macroeconomics.

Dan holds a bachelor's degree from Oberlin College and a master's degree from Columbia University.

Disclosure: Dan does not trade individual stocks or securities. He is eternally long the U.S equity market, primarily through tax-advantaged accounts.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayAnother worrying bout of late-session weakness couldn't take down the main equity indexes on Wednesday.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

Big Change Coming to the Federal Reserve

Big Change Coming to the Federal ReserveThe Lette A new chairman of the Federal Reserve has been named. What will this mean for the economy?

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into AMD Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into AMD Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayAdvanced Micro Devices stock is soaring thanks to AI, but as a buy-and-hold bet, it's been a market laggard.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into UPS Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into UPS Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayUnited Parcel Service stock has been a massive long-term laggard.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Lowe's Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Lowe's Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayLowe's stock has delivered disappointing returns recently, but it's been a great holding for truly patient investors.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into 3M Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into 3M Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayMMM stock has been a pit of despair for truly long-term shareholders.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Coca-Cola Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Coca-Cola Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayEven with its reliable dividend growth and generous stock buybacks, Coca-Cola has underperformed the broad market in the long term.

-

If You Put $1,000 into Qualcomm Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You Would Have Today

If You Put $1,000 into Qualcomm Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You Would Have TodayQualcomm stock has been a big disappointment for truly long-term investors.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Home Depot Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Home Depot Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayHome Depot stock has been a buy-and-hold banger for truly long-term investors.