What Corporate Profits Really Tell You

You need to go beyond the headlines to interpret a company’s earnings.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Stock investors of all stripes care about corporate earnings. Lovers of fast-growing firms prefer profits growing at a high, compounding rate, for example, and those looking for undervalued names may covet firms whose stock prices look cheap in comparison to earnings per share. Lately, the earnings picture for the broad stock market has been cloudier than ever, frustrating professional and armchair analysts alike.

Given the dire economic circumstances of the pandemic-induced recession, the expectations for corporate profits for the second quarter were beyond bleak. And yet, by early August, with close to 90% of S&P 500 companies having reported earnings for the quarter than ended in June, nearly 82% of them had exceeded Wall Street’s dismal expectations, by an average of nearly 18%, according to investment research firm Refinitiv—the highest “earnings beat” percentages since Refinitiv began tracking earnings data in 1994.

But exceeding such a low bar isn’t much to celebrate, and the market responded to the better-than-expected quarter with a collective shrug. When reports are all in, profits for the quarter still are expected to have declined by 33.9% from the same quarter a year ago, per Refinitiv. “That kind of collapse in S&P 500 earnings is not going to turn bears into bulls, especially at high stock valuations and given ongoing COVID-19 uncertainty,” says Jeff Buchbinder, a market strategist at investment research firm LPL Financial.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Where earnings are headed in the second half of 2020 is still difficult to divine given the uncertainty surrounding the reopening of the economy, Buchbinder says. “Until we get a vaccine, or dramatic leaps forward in treatments that make people comfortable resuming some semblance of normal life, earnings will have an extremely difficult time returning to pre-pandemic levels,” he says.

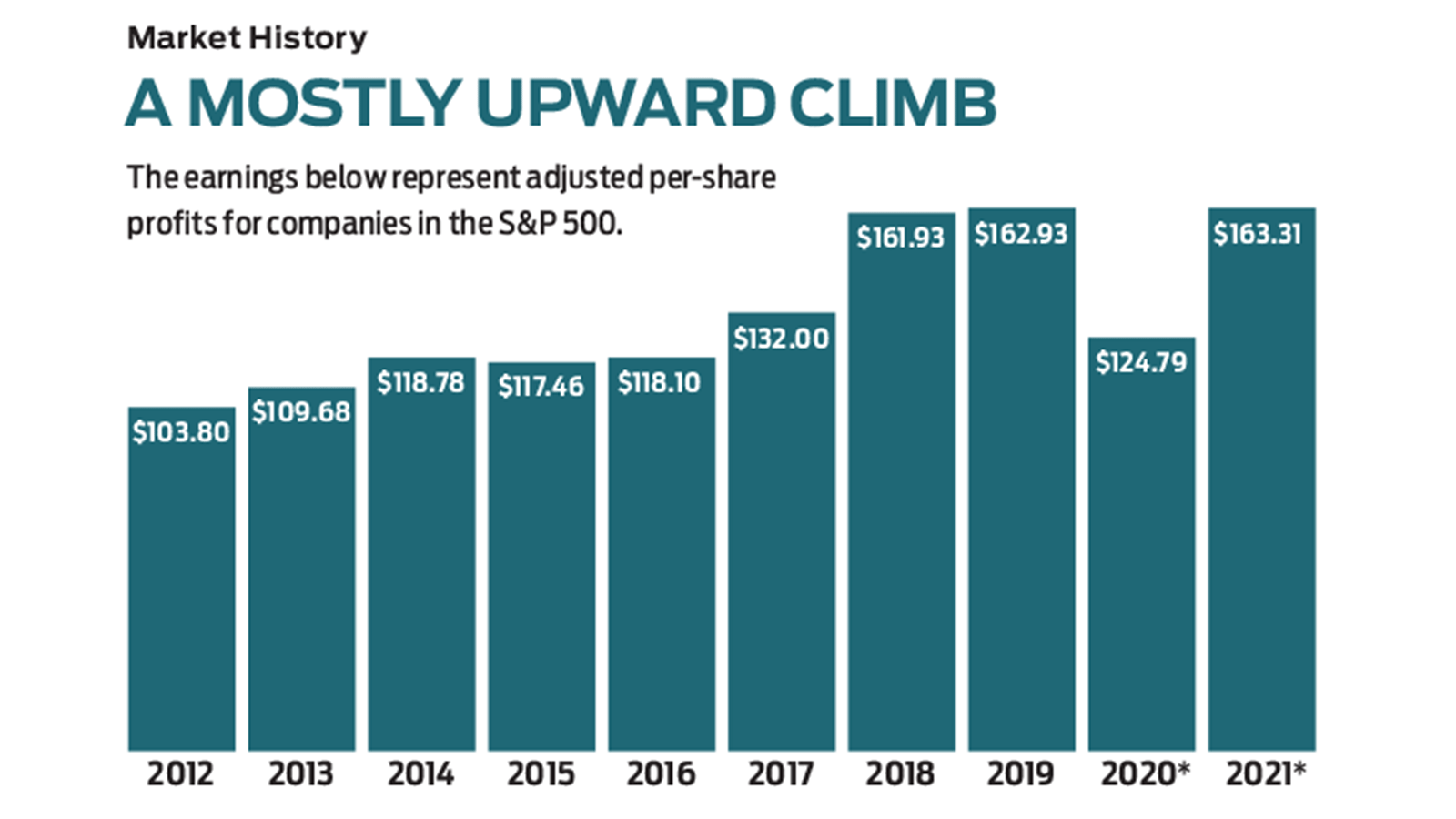

Making things trickier for market prognosticators: About half of the companies in the S&P 500 have rescinded the guidance they usually supply regarding sales and profit expectations for 2020. So, with perhaps a little less confidence in their forecasts than usual, Wall Street analysts expect per-share earnings for S&P 500 companies overall to fall 23% for the calendar year, followed by a 31% bounce in 2021.

Behind the numbers. As if there wasn’t enough uncertainty, investors should be aware that even in normal years, an analysis of corporate profits—the main driver of stock market returns over time—isn’t as straightforward as it would appear from the business-news headlines. In fact, there are frequently two versions of earnings for any given company in any given quarter. If you are assessing an individual stock, it’s important to be clear about which version you’re looking at, and why.

It may surprise you to learn that the accounting of corporate profits required by law in every publicly traded company’s earnings statement is frequently not the version touted in the news. The “official” statement must include GAAP earnings—those that adhere to generally accepted accounting principles. GAAP rules aim to standardize accounting practices for all U.S. firms, providing a level playing field for companies reporting their profits and a way for investors to make apples-to-apples comparisons of companies in different industries.

But because GAAP standards require companies to bake certain expenses into their earnings numbers—costs that corporate execs say don’t reflect a firm’s true operating performance—most companies report non-GAAP earnings as well. Often listed as “adjusted” or “core” earnings, these numbers strip out (among other things) one-time, non-recurring charges such as costs associated with acquisitions, litigation or corporate restructuring. This version is likely the one you’ll see heading up earnings press releases, in stock write-ups by investment analysts, and in the figures quoted atop this article. This style of financial reporting has become ubiquitous: A study from Audit Analytics found that 97% of S&P 500 firms included non-GAAP metrics in their financial statements in 2017, up from 59% in 1996.

Adjusting for the pandemic. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has given a shock to many firms’ operations, non-GAAP measures can be helpful for understanding what’s going on in the business, says Morningstar global data director for equity research Adrien Cloutier. “But you have to watch your step. These adjustments are made at management’s discretion. It’s not the least biased view,” he says.

Even in less eventful years, the adjustments can be major. Take data analysis software firm Splunk, whose shares have returned 52% over the past 12 months. In the 12 months ending January 31, the firm recorded a GAAP operating loss of $2.22 per share. But after stripping out stock-based compensation for employees (a common convention among small, fast-growing tech firms), a legal settlement charge and costs associated with an acquisition, among other expenses, the firm arrived at a non-GAAP profit of $1.88 per share.

A big discrepancy between GAAP and non-GAAP earnings on its own doesn’t mean that executives are misleading shareholders, but it could be a sign that you’re comparing apples to oranges if peer firms are not making similar adjustments. And as pandemic-related expenses work their way through earnings this year, it behooves investors to scrutinize management’s reasoning behind adjustments, says Jason Herried, equity strategy director at Johnson Financial Group. “Expenses being treated as one-time items that really sound more like part of regular business operations are a potential red flag,” he says. Morningstar’s Cloutier recommends examining how a firm has reported earnings over time. “A one-time restructuring cost may be a legitimate adjustment. But if a company is adjusting for restructuring year after year, that isn’t a one-time thing,” he says.

If you’re skeptical of the quality of a firm’s earnings, look for other hallmarks of financial health, says fund manager Joseph Shaposhnik at TCW New Americas Premier Equities. Companies with net cash (total cash on the balance sheet exceeding total liabilities) and consistently high levels of free cash flow (cash profits after spending to maintain and improve the business) are likely to be healthy businesses. “If a company generated ample cash even in the depths of the pandemic, you can be pretty sure it can survive through the other side of the crisis,” he says.

Ask yourself if the firm would be able to service its debt over the next two years if operations remained at the depressed levels of the second quarter. “Clearly, no firm can operate indefinitely with a 90% reduction of business,” says Herried.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Ryan joined Kiplinger in the fall of 2013. He wrote and fact-checked stories that appeared in Kiplinger's Personal Finance magazine and on Kiplinger.com. He previously interned for the CBS Evening News investigative team and worked as a copy editor and features columnist at the GW Hatchet. He holds a BA in English and creative writing from George Washington University.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayAnother worrying bout of late-session weakness couldn't take down the main equity indexes on Wednesday.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

Best Banks for High-Net-Worth Clients

Best Banks for High-Net-Worth Clientswealth management These banks welcome customers who keep high balances in deposit and investment accounts, showering them with fee breaks and access to financial-planning services.

-

Stock Market Holidays in 2026: NYSE, NASDAQ and Wall Street Holidays

Stock Market Holidays in 2026: NYSE, NASDAQ and Wall Street HolidaysMarkets When are the stock market holidays? Here, we look at which days the NYSE, Nasdaq and bond markets are off in 2026.

-

Stock Market Trading Hours: What Time Is the Stock Market Open Today?

Stock Market Trading Hours: What Time Is the Stock Market Open Today?Markets When does the market open? While the stock market has regular hours, trading doesn't necessarily stop when the major exchanges close.

-

Bogleheads Stay the Course

Bogleheads Stay the CourseBears and market volatility don’t scare these die-hard Vanguard investors.

-

The Current I-Bond Rate Is Mildly Attractive. Here's Why.

The Current I-Bond Rate Is Mildly Attractive. Here's Why.Investing for Income The current I-bond rate is active until April 2026 and presents an attractive value, if not as attractive as in the recent past.

-

What Are I-Bonds? Inflation Made Them Popular. What Now?

What Are I-Bonds? Inflation Made Them Popular. What Now?savings bonds Inflation has made Series I savings bonds, known as I-bonds, enormously popular with risk-averse investors. How do they work?

-

This New Sustainable ETF’s Pitch? Give Back Profits.

This New Sustainable ETF’s Pitch? Give Back Profits.investing Newday’s ETF partners with UNICEF and other groups.

-

As the Market Falls, New Retirees Need a Plan

As the Market Falls, New Retirees Need a Planretirement If you’re in the early stages of your retirement, you’re likely in a rough spot watching your portfolio shrink. We have some strategies to make the best of things.