Live Well Without Running Out of Money in Retirement

These money-generating tactics will help retirement savers enjoy their golden years without stressing over cash.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

As you near retirement, you might look back and think that saving for this next stage of life was the easy part. During your working years, the big decisions were how much to save and where to invest. But now it’s time to switch gears. Instead of accumulating assets, you must figure out how to turn your nest egg into an income stream to last a lifetime.

“The idea of withdrawing from their retirement portfolio is really painful for a lot of people. They’re savers,” says John Bohnsack, a certified financial planner in College Station, Texas.

Here are steps that can help you generate the retirement income you will need. Along the way, you’ll need to answer some questions: Will you get a part-time job in retirement that brings in some income? When should you claim Social Security or start taking your pension, if you have one? And how will you address the big uncertainties of health care and long-term care? Taxes will get more complicated because, unlike previous generations, most retirees today have the bulk of their retirement money tied up in tax-deferred 401(k)s and traditional IRAs. How do you withdraw from these accounts safely without triggering a big tax bill?

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Begin With a Budget

Get a handle on what your annual expenses will be in retirement by creating a retirement budget. Frank Castello, a 66-year-old former IT manager from Bowie, Md., gave his retirement budget a test run before leaving the workforce in 2016. He drew up a spreadsheet with his anticipated expenses, calculating that he would need $4,000 a month to live on. He lived on that budget for two years before retiring, while also maxing out his 401(k) and boosting his savings outside the plan. “I was constantly refiguring, rejiggering, verifying and validating the numbers,” says Castello. “Do I have it right? Will I have enough? You don’t know for sure until you live it.”

So far, it’s worked out for him. Castello, who isn’t married, lives on savings and a $1,490 monthly pension. He rolled his 401(k) into an IRA that is 63% invested in stocks, with the rest mostly in bonds—an account he hasn’t touched yet. He has enough cash on hand to pay expenses for a few years without having to worry about stock market fluctuations, and he has set up an emergency fund that he might need to tap when his 2005 Acura TL finally gives out. And Castello is waiting until age 70 to claim Social Security to get the maximum benefit. “I’m healthy. I don’t need the money now,” he says.

Take a look at what you’ve spent in the past year. (If you don’t track your expenses now, your credit card issuers may offer a year-end summary of your charges to get you started.) Then adjust those expenses for what might change in retirement. For instance, you won’t be commuting to work anymore, but you might be traveling to more far-flung destinations.

Or you might decide to tackle some major home renovations. “I always joke with clients, ‘Look around your house and see what you want to change and start planning for it,’” says Nicole Strbich, a CFP in Alexandria, Va. Because once you retire, you’re going to sit in your living room and decide you need new carpet, a kitchen renovation and a bigger porch, she says. (Renovations often end up costing more than projected, so Strbich advises doing them just before retiring, while you still have a paycheck to cover any surprise bills.)

Take a look at what you've spent in the past year ... Then adjust those expenses for what might change in retirement.

Don’t overlook health care surprises, either, especially if you plan to retire early. Judy Freedman of Marlton, N.J., retired six years ago as a group director in global communications at Campbell Soup. Too young for Medicare—she’s now 61—Freedman pays more than $1,000 a month for the retiree medical plan through her former employer. And though she has a dental policy that covers the basics, such as teeth cleaning, expensive dental work has to be paid out of pocket. (After you sign up for Medicare, you’ll need a supplemental policy to provide dental coverage.) Before retiring, Freedman, a widow, cut her expenses by downsizing. She sold her three-bedroom ranch house on a large lot and moved into a townhouse community, which reduced her property taxes, utilities and landscaping bills.

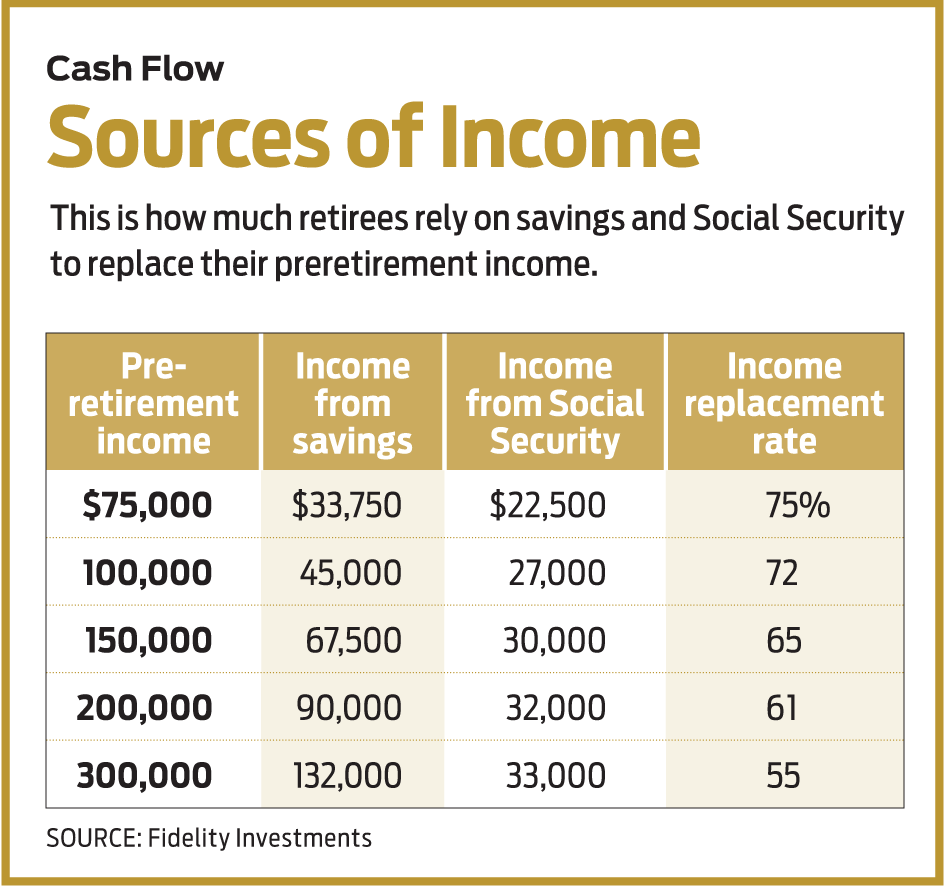

Once you’ve nailed down your anticipated expenses, subtract all your expected guaranteed sources of income, such as a pension, annuity and Social Security. (You can get an estimate of your future Social Security benefit by opening an online account at www.ssa.gov/myaccount.) The result is how much you will need to withdraw from your portfolio to maintain your lifestyle in retirement.

Make Withdrawals Last as Long as You Do

What if your expenses outpace your sources of income, meaning you’re likely to deplete your nest egg too quickly? In that case, you may need to consider working longer or go back to your retirement budget and figure out what expenses you can cut.

But knowing whether you’re withdrawing money too quickly from your nest egg can be tricky: You don’t know how many years you’ll live in retirement, and you can’t count on earning the returns that we’ve enjoyed in the decade-long bull market. “If you do it in a careful and measured way, you can make withdrawals and, even if your account drops in value, not necessarily run out of money,” says Tim Steffen, director of advanced planning for Baird in Milwaukee.

One popular guideline has been the 4% rule, which was designed in the 1990s as a safe withdrawal rate for a 30-year retirement that may include bear markets and periods of high inflation. It assumes half of your retirement portfolio is in stocks and the other half is in bonds and cash.

The rule works like this: Retirees draw 4% from their portfolio in the first year of retirement. Then they adjust the dollar amount annually by the previous year’s rate of inflation. So with a $1 million portfolio, your withdrawal in your first year of retirement would be $40,000. If inflation that year goes up 3%, the next year’s withdrawal would be $41,200. If inflation then drops to 2%, the withdrawal for the following year would be $42,024.

The 4% rule is a good starting point but may need some fine-tuning to fit your own situation, says Maria Bruno, head of U.S. wealth planning research at Vanguard. “Are you retiring at a younger age? If so, you might need a lower withdrawal rate.” You may also need to withdraw your money more slowly if you are investing more conservatively, she adds.

Michael Kitces, director of wealth management at Pinnacle Advisory in Columbia, Md., says that while the 4% rule protects portfolios under bad-case scenarios, retirees could experience the opposite and end up after 30 years with more than double what they started with—even after decades of withdrawals. He suggests that if you use the rule, you review your portfolio every three years. Anytime it rises 50% above the starting point—say, a $1 million portfolio grows to $1.5 million—increase the dollar amount you withdraw that year by 10%. Then you can resume increasing that dollar amount by the rate of inflation until your portfolio grows significantly again to warrant a raise. (Of course, if you want to leave a legacy for your heirs, you may want to keep your money invested.)

Manage Your Portfolio

Inflation is relatively low today, but even at current rates, it can greatly erode your purchasing power over a long retirement. And the Consumer Price Index, the most popular gauge of inflation, may be undercounting your expenses in retirement. The CPI-E, a government index that gauges the rise in prices for households age 62 and older, averaged 1.86% annually over the past decade, slightly higher than the general inflation rate. That’s because older households devote more of their budget to health care, and the cost of that has risen faster than the general inflation rate.

To keep up with inflation, your portfolio will need the kind of long-term growth that stocks can provide. The right amount for you depends on how much risk your nerves can handle, along with your other assets and sources of income. If you’re near retirement or newly retired, Vanguard’s Bruno recommends a diversified portfolio with 40% to 60% in stocks.

Are you retiring at a younger age? If so, you might need a lower withdrawal rate. You may also need to withdraw your money more slowly if you're investing more conservatively.

Investors may have grown complacent in a bull market that’s now close to being in its 11th year, but a bear is inevitable. Given the long run of this bull market, there is an elevated risk of a bear on the horizon, says Kitces.

A bear market can be devastating if it strikes early in retirement and you are forced to sell investments at a loss to pay bills. One way to lessen the impact of this, says Kitces, is to reduce your exposure to stocks as you head into retirement. If you’re, say, 50% in stocks, reduce that to 40% or 30%, he says. When the market falls, you can use that opportunity to buy stocks at lower prices and boost your holdings back to 50% of your portfolio, he says.

Another way to protect yourself during a market downturn—and preserve your peace of mind—is to use the bucket system. You divide your money into three buckets based on when you’ll need it. Bucket One holds enough cash for living expenses in the first one or two years of retirement that won’t be covered by a pension, an annuity or Social Security. Bucket Two is made up of money you will need within the next 10 years and can be invested in, say, short- and intermediate-term bond funds. Bucket Three is the money you won’t need until much later, so it can be invested in stocks or even alternative investments, such as real estate or commodities. (Review your cash bucket annually to see if it needs to be replenished from one of the other buckets.)

With the bucket system, even if the stock market plummets, you have the comfort of knowing that you have enough money in the first two buckets to cover your expenses for years without selling your stocks for a loss (see Make Your Money Last).

Plan for Health Care

Vanguard’s research last year estimated that the typical 65-year-old woman pays $5,200 annually in health costs, including Medicare premiums and other out-of-pocket medical expenses. The cost nearly doubles by age 85, to $10,100 annually. “Health care is the biggest wild card,” says Elliot Herman, a CFP in Quincy, Mass. The only sure thing about it is that the cost will rise over time.

To help with medical bills in retirement, consider opening a health savings account while you’re still working, if you have a high-deductible health insurance policy. “We sometimes say an HSA is a Roth on steroids,” says Vanguard’s Bruno. You get a triple tax-free benefit: Contributions aren’t taxed, they grow tax-deferred, and the money can be used tax-free for eligible medical expenses. And recent changes in HSA rules for those with chronic conditions make these accounts even more attractive.

For 2019, you can contribute up to $3,500 if you have single coverage and as much as $7,000 for family coverage. To make the most of the HSA, pay current medical bills out of pocket (if you can afford to), so the account has more time to grow. You can’t contribute to an HSA once you enroll in Medicare, even if you’re still working, but you can use the money at any time to pay medical bills, including Medicare Part B and Part D premiums.

Long-term care, which isn’t covered by Medicare, is another uncertainty that retirees need to address. You may never need long-term care, but if you do, the bill can be huge. A study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimated that nearly half of people who are now 65—or who reached that age in the past few years—won’t have any long-term-care costs. But one-fourth are expected to face long-term-care bills of up to $100,000, and 15% will rack up costs of $250,000 or more.

If you have the assets, you could pay the bills out of pocket. Long-term-care insurance is also an option, although it can be expensive, and you may have a difficult time finding a policy if you have a health issue (see How to Afford Long-Term Care).

Kitces advises buying a policy while you’re in your fifties, when the cost is lower and you’re likely still healthy enough to qualify for a policy. Policies are much more expensive than those issued many years ago, but the higher price also reduces the risk of steep rate hikes in the future, says Kitces.

Long-term care, which isn't covered by Medicare, is another uncertainty that retirees need to address. You may never need it, but if you do, the bill can be huge.

Some people resist buying long-term-care insurance, thinking it will be a waste of money if they never need care, says Keith Bernhardt, vice president of retirement income at Fidelity Investments. The solution for them, he says, can be a hybrid policy that combines long-term-care and life insurance benefits. It will cover bills for long-term care, but if you never need care (or need only little of it) your heirs will receive a death benefit when you die. “It helps to remove that concern that ‘I won’t get a benefit from this,’ ” Bernhardt says. Be aware that the policy is doing double-duty, so premiums are significantly higher than if you purchased a stand-alone long-term-care policy. An independent insurance broker can help you find a policy among different companies.

Getting Guaranteed Income

A traditional pension will provide guaranteed income for life. Although more than 80% of state and local government workers have access to a pension, only about 17% of private-sector workers can access that type of retirement plan, according to the Alliance for Lifetime Income, a nonprofit that represents insurance companies and other financial institutions.

If you’re not in the fortunate group, an immediate annuity provides a way to create your own pension, using money you’ve saved in your 401(k) or elsewhere. In exchange for a lump sum, an insurance company will provide you with a monthly payment, usually for the rest of your life. Variable and equity-indexed annuities can also provide guaranteed income in retirement, but the amount may fluctuate depending on the performance of an underlying investment portfolio. These annuities are more complex than immediate annuities and often come with high fees.

A popular strategy is to buy an immediate annuity that will cover your monthly expenses, such as utilities and food. If a bear market hits, you’ll have the flexibility to wait until the stock market recovers before taking withdrawals from your portfolio (although you may have to postpone your winter Caribbean island cruise).

There are downsides to annuities to consider before you write a check. Once you give an insurance company your money, you usually can’t get it back, although some insurance companies allow one-time withdrawals for certain emergencies. Another drawback is that inflation will erode the value of your payments over time. Most insurance companies offer immediate annuities with an inflation rider—for example, payments will increase by 3% a year—but that will lower your initial payouts by up to 28%. For example, if a 65-year-old man invested $100,000 in a New York Life immediate annuity with no inflation rider, he would receive $6,197 a year. If he added a 3% annual inflation adjustment, his first annual payout would be only $4,446.

Supporters of the law say it would help workers convert their savings into lifetime payouts when they retire. But critics say the legislation doesn’t go far enough to prevent employers from offering complex variable and equity-indexed annuities that are burdened with high fees—a common problem with many 403(b) annuity offerings. You may be better off investing your savings in low-cost mutual funds or exchange-traded funds and buying an immediate or deferred annuity after you retire.

Your Home as a Safety Net

Reverse mortgages have often been branded as a way for older retirees to raise money only when other sources of retirement income have dried up. But a growing group of financial planners and academics say that taking out a reverse mortgage early in retirement could help protect your retirement income from stock market volatility and significantly reduce the risk that you’ll run out of money.

Here’s how the strategy, known as a standby reverse mortgage, works: Take out a reverse mortgage line of credit as early as possible—homeowners are eligible at age 62—and set it aside. If the stock market turns bearish, draw from the line of credit to

pay expenses until your portfolio recovers. Retirees who adopt this strategy should be able to avoid the pitfalls of the Great Recession, when many seniors were forced to take money out of severely depressed portfolios to pay the bills.

The standby reverse mortgage strategy can be effective “both from a practical and a behavioral perspective,” says Evensky. “If people know they’ve got resources when the market collapses, they don’t panic and sell.”

A traditional home-equity line of credit could also provide a source of emergency cash, but you can’t count on the money being there when you need it, says Shelley Giordano, founder of the Academy for Home Equity in Financial Planning at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign.

During the 2008–09 market downturn and credit crunch, many banks froze or closed borrowers’ home-equity lines. “Just when people needed money and liquidity, the banks needed liquidity, too,” says Giordano. That won’t happen if you have a reverse mortgage line of credit. As long as you meet the terms of the reverse mortgage—you must maintain your home and pay taxes and insurance—your line of credit is guaranteed.

Several factors make a standby reverse mortgage particularly attractive now. Homeowners age 62 and older have seen the amount of equity in their homes increase sharply in recent years, to a record $7.14 trillion in the first quarter of 2019, according to the National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association.

Low interest rates are another plus. Under the terms of the government-insured Home Equity Conversion Mortgage, the most popular kind of reverse mortgage, the lower the interest rate, the more home equity you’re allowed to borrow.

Which leads us to one of the most counterintuitive—and potentially lucrative—features of reverse mortgages. Your untapped credit line will increase as if you were paying interest on the balance, even though you don’t have to pay interest on money you don’t tap. If interest rates increase—and given current low rates, they are almost guaranteed to move higher eventually—your line of credit will grow even faster, says Giordano.

You won’t have to pay back money you tap as long as you remain in your home, a comforting thought if you take money during a bear market. A HECM reverse mortgage is a “non-recourse” loan, which means the amount you or your heirs owe when the home is sold will never exceed the value of the home. For example, if your loan balance grows to $300,000 and your home is sold for $220,000, you (or your heirs) will never owe more than $220,000. The Federal Housing Administration insurance will reimburse the lender for the difference.

If you have an existing mortgage, you’ll have to use the proceeds from your reverse mortgage to pay that off first. You have plenty of flexibility: Funds left over can be taken as a line of credit, a lump sum, monthly payments or a combination of those options. Even if there’s not a lot of money left over, paying off your first mortgage means you won’t have to withdraw money to make mortgage payments during a market downturn, Giordano says. “A regular mortgage that requires a monthly principal and interest payment can be a real burden, especially when the value of your portfolio is under stress,” she says.

Under the terms of the government-insured Home Equity Conversion Mortgage, the lower the interest rate, the more home equity you're allowed to borrow.

The drawbacks. One of the biggest downsides to reverse mortgages is the up-front cost, which is significantly higher than the cost of a traditional home-equity line of credit. The FHA says lenders can charge an origination fee equal to the greater of $2,500 or 2% of your home’s value (up to the first $200,000), plus 1% of the amount over $200,000, up to a cap of $6,000. You’ll also be charged an up-front mortgage insurance premium equal to 2% of your home’s appraised value or the FHA lending limit of $726,525, whichever is less. And you’ll have to pay third parties for an appraisal, title search and other services. You can pay for some of these costs with the proceeds from your loan, but that will reduce the loan balance. Costs vary, so talk to at least three lenders that offer reverse mortgages, says Giordano.

Because of the up-front costs, it’s rarely a good idea to take out a reverse mortgage unless you expect to stay in your home for at least five years. Remember, too, that the loan will come due when the last surviving borrower sells, leaves for more than 12 months due to illness, or dies.

If your heirs want to keep the home, they’ll need to pay off the loan first. That may not sit well with children who expect to inherit the family homestead, so it’s a good idea to discuss your plans with them in advance. Giordano doesn’t see this as a big barrier to a standby reverse mortgage—especially if it helps you preserve other, more liquid assets. “Kids would much rather split up a big fat portfolio than try to decide how to split up the house,” she says.

Yes, this new phase of life comes with a lot of uncertainties. And financial advisers say that many new retirees often hold back on spending because of all the unknown bills that may await years down the line. But Fidelity’s Bernhardt says these retirees often discover a happy surprise.

“They actually find out that they are in a pretty good spot. They are able to be happy and enjoy retirement,” he says. “It’s not quite as expensive as they thought it was going to be.”

Tax-Smart Strategies

The conventional wisdom to minimize taxes in retirement is to draw first from taxable accounts, which are generally taxed at favorable long-term capital gains tax rates (as low as zero but no higher than 23.8%); then tap tax-deferred accounts, such as traditional IRAs and 401(k)s, whose withdrawals are taxed as ordinary income; and dip into Roth IRAs last so this tax-free money has more time to grow.

But if you’re approaching retirement with the bulk of your assets in a 401(k) or traditional IRA, consider a slight break with convention. The IRS requires you to begin minimum withdrawals from tax-deferred accounts after age 70½—so it can finally start collecting income taxes on the money. (Legislation pending in Congress would raise that age to 72.) But if your balances are large enough, these mandatory withdrawals could throw you into a higher tax bracket.

“The crop of retirees that are leaving the workforce today is the RMD generation,” says Maria Bruno, head of U.S. wealth planning research at Vanguard. “These are folks leaving the workforce with large tax-deferred balances.”

It’s not too late to reduce future RMDs if you’re still in your sixties. “We call this the sweet spot,” says Bruno. One tax strategy is to draw from tax-deferred accounts early in retirement, when you might be in a lower tax bracket, and use the money to help with living expenses while delaying Social Security. Or, if you don’t need the cash to live on, you can gradually convert some tax-deferred money into a Roth IRA.

In either case, make sure you don’t withdraw or convert too much money in a single year and push yourself into a higher tax bracket. It’s a good idea to visit an accountant or financial adviser to make sure you don’t trigger any unintended tax consequences.

How to Get More From a Smaller Pie

The Society of Actuaries and the Stanford Center on Longevity have developed a withdrawal strategy geared for middle-income workers with less than $1 million in savings—people who often don’t work with financial advisers. This Spend Safely in Retirement Strategy relies on optimizing Social Security benefits, which ideally you would delay until age 70. “That’s the cornerstone of the strategy,” says Steve Vernon, research scholar at the Stanford Center on Longevity and author of Retirement Game-Changers.

Social Security retirement benefits can start as early as 62, but taking them that early will reduce your monthly check by up to 30% compared with waiting until your full retirement age (66½ for those turning 62 this year). And for every year you delay benefits past your full retirement age, your benefit grows by 8%. Few retirees (only 4%) delay Social Security until age 70, according to a new study that calculated that today’s retirees are losing out on an average of $111,000 per household during retirement by claiming benefits early.

Vernon acknowledges that it’s a challenge to get people to delay claiming. But Spend Safely aims to get over this hurdle with a strategy to generate income in your sixties without Social Security: Pull the amount from your portfolio each year that you would have received from Social Security had you claimed benefits. (If you’re earning money from a part-time job, that will reduce the amount you will need to pull out.) On top of that, withdraw an amount at a rate modeled after the required minimum distributions that older savers must take from tax-deferred accounts after age 70½. This Spend Safely rate starts at 2.7% of the year-end portfolio balance at age 60 and gradually raises that to 3.6% at 70. Thereafter, you would use the RMD withdrawal rates published by the IRS.

Vernon says retirees can tweak this method, say, to boost their travel budget in the early years, although that would mean reducing withdrawals later. One drawback: Annual withdrawals will go up and down with the investment portfolio’s performance each year.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Loses 821 Points to Open Nvidia Week: Stock Market Today

Dow Loses 821 Points to Open Nvidia Week: Stock Market TodayU.S. stock market indexes reflect global uncertainty about artificial intelligence and Trump administration trade policy.

-

Nvidia Earnings: Live Updates and Commentary February 2026

Nvidia Earnings: Live Updates and Commentary February 2026Nvidia's earnings event is just days away and Wall Street's attention is zeroed in on the AI bellwether's fourth-quarter results.

-

I Thought My Retirement Was Set — Until I Answered These 3 Questions

I Thought My Retirement Was Set — Until I Answered These 3 QuestionsI'm a retirement writer. Three deceptively simple questions helped me focus my retirement and life priorities.

-

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should Know

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should KnowMedicare Part A and Part B leave gaps in your healthcare coverage. But Medicare Advantage has problems, too.

-

15 Reasons You'll Regret an RV in Retirement

15 Reasons You'll Regret an RV in RetirementMaking Your Money Last Here's why you might regret an RV in retirement. RV-savvy retirees talk about the downsides of spending retirement in a motorhome, travel trailer, fifth wheel, or other recreational vehicle.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits in 2026. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Estate Planning Checklist: 13 Smart Moves

Estate Planning Checklist: 13 Smart Movesretirement Follow this estate planning checklist for you (and your heirs) to hold on to more of your hard-earned money.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.

-

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026SEP IRA A good option for small business owners, SEP IRAs allow individual annual contributions of as much as $70,000 in 2025, and up to $72,000 in 2026.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.