Should You Be an Index Investor?

Although index funds offer quite a few benefits, rock-bottom expenses are most significant.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

The advantages of index funds are hardly secret. It has become an annual ritual for data companies to release a tally of the relatively poor performance of actively managed funds during the previous calendar year. Last year’s casualties: Only 34% of actively managed funds that invest in large-company U.S. stocks managed to beat Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index, and just 28% of active funds that invest in small companies beat their benchmark, according to S&P Global.

Look long term, and the picture grows even grimmer for actively managed funds. Over the past 10 years, just 18% of active large-company U.S. stock funds have beaten the S&P 500, according to S&P. Among all the asset classes S&P tracks—including large- and small-company funds, growth and value funds, international stock funds and bond funds—not a single category of active funds has, on average, managed to beat its relevant index over the past decade.

Does this mean it’s a fool’s errand ever to invest in an actively managed fund? Hardly. After all, no one invests in the average fund. In fact, no less an indexing proponent than Vanguard has found that its own actively managed funds have on average beaten their respective indexes over the long term. And American Funds has found that its own stock funds have beaten their indexes in almost every 30-year period since 1934. Costs are eminently important in picking winning active funds. The difficulty for investors is that, beyond that, there’s no magic formula. Investors must identify talented managers and stick with them.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

However, the record shows that you would be perfectly justified to throw in the towel on active management if you want to skip out on the rat race of trying to pick winning managers. When investing with a top manager, you place a bet on hopes of boosting your returns. But lowering your expenses, by investing in inexpensive index funds, offers a guaranteed payoff.

Although index funds offer quite a few benefits, rock-bottom expenses are most significant. “It is impossible to overstate the importance of fees” to fund performance, says Ben Johnson, Morningstar’s director of global ETF research. Investors in actively managed funds pay average expense ratios of 0.78%; investors in index funds pay 0.18% on average, according to Morningstar. Those lower expense ratios reflect the fact that index funds can skip paying for pricey research. But index funds also save big by trading much less than actively managed funds. The costs of buying and selling investments inside a fund are an invisible expense—they aren’t factored in to funds’ expense ratios and aren’t detailed in fund documents—but are estimated to average about 1% annually and to reach as much as 2% or more for high-turnover funds.

Lower Fees, Less Turnover

Those fee differences may not alarm you (one percentage point here or there sounds harmless), but don’t let those small numbers comfort you. Burton Malkiel, the author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street and chief investment officer of robo adviser Wealthfront, says investors shouldn’t look at fees as a percentage of 100, but as a proportion of their returns.

Suppose a typical investor in an actively managed fund pays about 1.78% in total expenses annually (combining expense ratios and trading costs). If that investor expects to earn 7% annually before expenses, then the 1.78% costs actually represent more than one-fourth of his annual return. That’s bad enough, but over the long term the consequences become downright catastrophic. A $100,000 sum invested at 7% over 30 years will grow to about $760,000. However, subtract the 1.78% in annual fees, and the sum grows to only $460,000—a difference of $300,000. That investor missed out on an additional 65% of his nest egg, just by paying industry-average fees.

Recently, already rock-bottom fees among index funds have been falling to practically subterranean levels, thanks to a price war in the industry. In June, Fidelity announced fee cuts on 27 of its index funds and indexed exchange-traded funds, with the cheapest share class of its cheapest fund now charging just 0.015%, or 15 cents a year per $1,000 invested. The announcement followed similar cuts in the past year from most of the major players in the index-fund industry, including Vanguard, BlackRock (which manages the iShares family of ETFs) and Charles Schwab.

If paying just pennies in expenses isn’t reason enough to consider indexing, here are a few more things to love about index funds. Their low turnover makes them naturally tax-efficient, while their broad holdings make diversification a cinch. For investors who want to keep tight control over their asset allocation or their portfolio’s risk, index funds are a perfect fit. “With an index fund, you know what you own,” says Tim Courtney, chief investment officer of Exencial Wealth Advisors. “You get a set strategy, and you know that strategy’s not going to change based on a manager’s ideas at a particular moment in time.”

That being said, not all index funds are created equal. In the past decade, a horde of exotic ETFs have cropped up that, despite following indexes, offer none of the benefits of traditional index funds. Beware ETFs that track a narrow slice of the market, charge high expenses, use leverage or employ a quirky strategy in an effort to beat the market. And be cautious with exchange-traded notes, or ETNs. Although they are often marketed right alongside ETFs, ETNs are not funds at all, but rather unsecured debt instruments issued by financial institutions.

Stick with simplicity when choosing an index fund. Most plain-vanilla index funds weight their holdings according to market capitalization, meaning that larger companies take greater prominence. This type of strategy can hurt returns during market bubbles—in 2000, just before the dot-com bubble burst, for example, technology stocks accounted for almost 35% of the S&P 500 because they had risen so much in value. But a market-cap weighting is still your best bet. Unlike funkier approaches to weighting, “a market-cap weighting is the market,” Malkiel says. And because a cap-weighted index naturally adjusts its weightings as stock prices move up and down, it never has to trade stocks simply to accommodate price changes.

Where might index funds fit in your portfolio? Quite simply, anywhere. Over the long term, index funds have an edge over the average actively managed fund in every major asset class. If you’re committed to building a portfolio that blends index funds with some actively managed ones, consider using only low-cost active funds that you have very high confidence in, and filling in the rest of your portfolio with index funds.

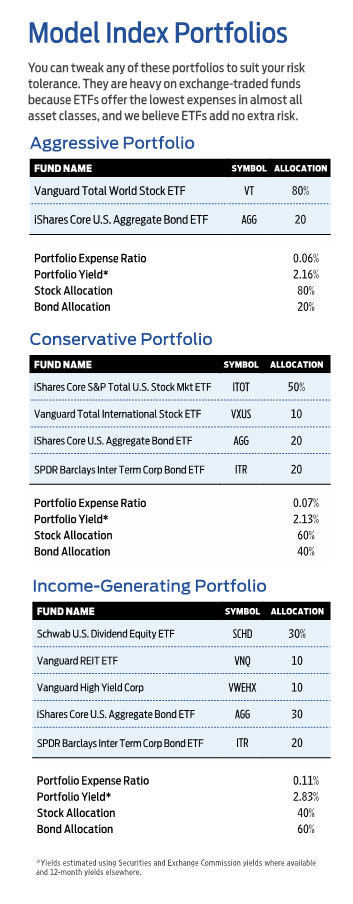

If you want to go index-only, we have created three model portfolios for your consideration, which you can tweak to suit your risk tolerance. The model portfolios are heavy on exchange-traded funds because efficiencies in ETFs’ share creation and redemption make them the cheapest option in almost all asset classes. If you prefer conventional index funds, there are plenty of good ones from fund families such as Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard that you can substitute for our picks.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayAnother worrying bout of late-session weakness couldn't take down the main equity indexes on Wednesday.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

Best Banks for High-Net-Worth Clients

Best Banks for High-Net-Worth Clientswealth management These banks welcome customers who keep high balances in deposit and investment accounts, showering them with fee breaks and access to financial-planning services.

-

Stock Market Holidays in 2026: NYSE, NASDAQ and Wall Street Holidays

Stock Market Holidays in 2026: NYSE, NASDAQ and Wall Street HolidaysMarkets When are the stock market holidays? Here, we look at which days the NYSE, Nasdaq and bond markets are off in 2026.

-

Stock Market Trading Hours: What Time Is the Stock Market Open Today?

Stock Market Trading Hours: What Time Is the Stock Market Open Today?Markets When does the market open? While the stock market has regular hours, trading doesn't necessarily stop when the major exchanges close.

-

Bogleheads Stay the Course

Bogleheads Stay the CourseBears and market volatility don’t scare these die-hard Vanguard investors.

-

The Current I-Bond Rate Is Mildly Attractive. Here's Why.

The Current I-Bond Rate Is Mildly Attractive. Here's Why.Investing for Income The current I-bond rate is active until April 2026 and presents an attractive value, if not as attractive as in the recent past.

-

What Are I-Bonds? Inflation Made Them Popular. What Now?

What Are I-Bonds? Inflation Made Them Popular. What Now?savings bonds Inflation has made Series I savings bonds, known as I-bonds, enormously popular with risk-averse investors. How do they work?

-

This New Sustainable ETF’s Pitch? Give Back Profits.

This New Sustainable ETF’s Pitch? Give Back Profits.investing Newday’s ETF partners with UNICEF and other groups.

-

As the Market Falls, New Retirees Need a Plan

As the Market Falls, New Retirees Need a Planretirement If you’re in the early stages of your retirement, you’re likely in a rough spot watching your portfolio shrink. We have some strategies to make the best of things.