Luxury Stocks: Profit from Indulgence

Luxury-goods houses ride high on the power of individual brands—names that evoke style, quality and endurance.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

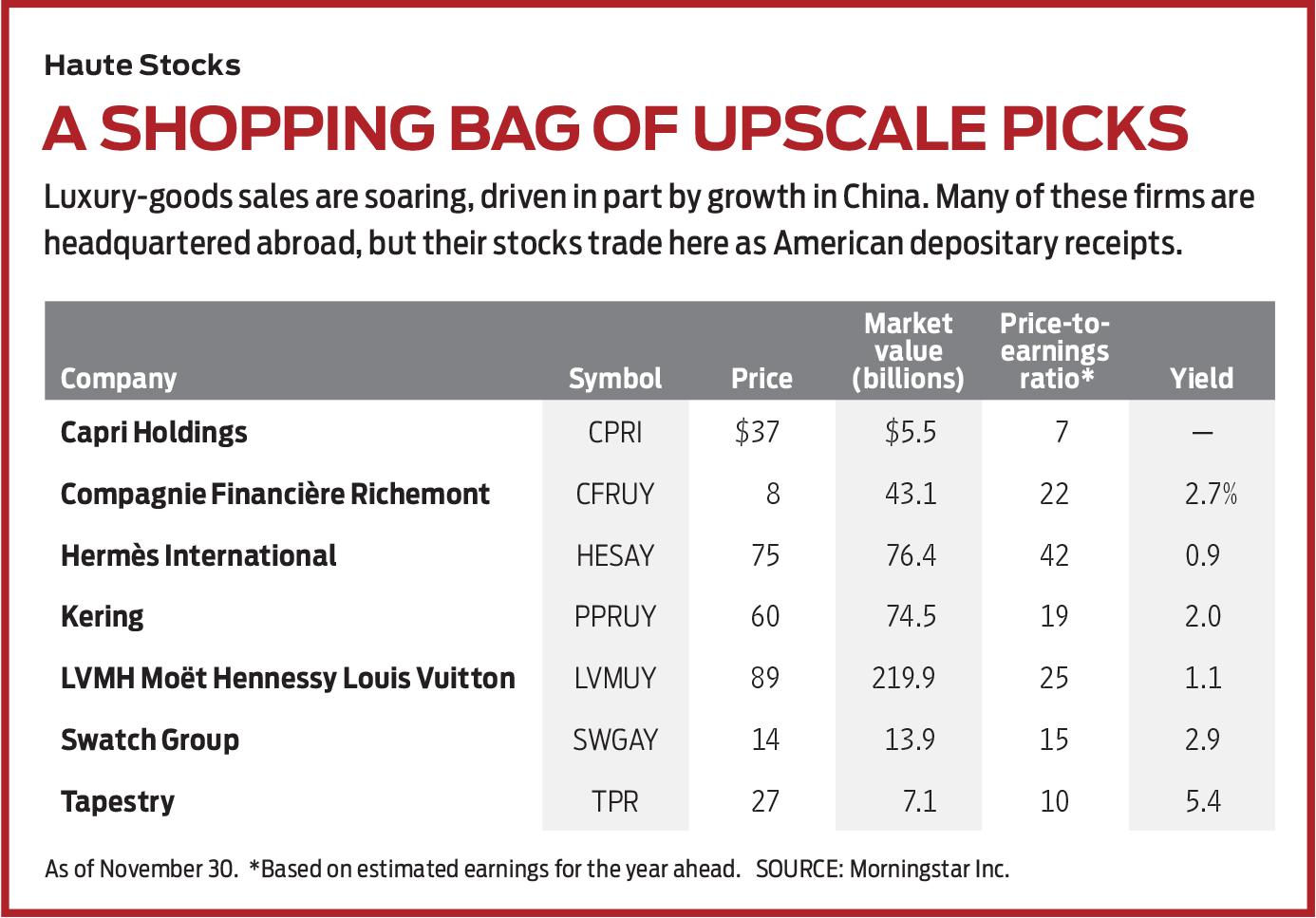

Not long ago, a young American woman I know well was on vacation in Paris and decided she would splurge on her favorite luxury brand. She went to the Hermès store on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré and bought a blue-and-gold blouse and a black skirt. Then, for the big purchase, she went back to the ground floor to buy a handbag. Hermès bags range from about $4,000 into the six figures. A salesperson told the woman she would have to send a text asking for a reservation the next day. The woman dutifully complied. Six hours later, a text (in French) came in response: “Because of a great number of requests, we cannot honor yours.” Hermès wouldn’t sell her a handbag!

Can there possibly be a better business than one in which demand so exceeds supply? Hermès International (symbol HESAY, $75) has found the formula. A harness and saddle maker founded in 1837, the company now sells all sorts of leather goods, as well as dresses, scarves, jewelry, furniture and more, in 310 stores around the world. With nearly 15,000 employees (9,000 of them in France), Hermès also manufactures goods for other luxury brands, including John Lobb shoes and Puiforcat tableware. The Dumas family—the fifth-richest in the world, with a net worth of $49 billion—controls Hermès, but the good news is that you can own stock yourself through American depositary receipts, which trade like any other shares on U.S. exchanges. (Prices, returns and other data are as of November 30.)

Business is booming. For the six months ending June 30, 2019, both sales and net profits rose 15% compared with the same period a year earlier. Hermès has made a big bet on Asia, where 41% of its stores are located (compared with just 13% in North America), and the wager is paying off. Unfortunately, the success is no secret. The stock has roughly doubled in the past three-and-a-half years, and it’s not cheap. But there are few other sectors that can offer this kind of growth.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

When money is no object. Luxury-goods companies are riding a wave. According to a survey by Credit Suisse, global millionaires (in U.S.-dollar terms) now number 47 million, accounting for 44% of the world’s wealth but less than 0.1% of the world’s population. You can decry this uneven distribution of riches, but you can also profit from it. According to Bain & Co., luxury-goods sales reached an estimated $300 billion in 2019, driven in large part by year-over-year growth of 18% to 20% in mainland China. Despite a slowdown in its economic growth rate, China has overtaken the U.S. as the country with the most rich people.

Luxury-goods companies benefit from the power of individual brands—names that reek of style and quality but also of longevity. Investors often speak of “moats,” or protection against cutthroat competition that leads to stolen customers and lower prices. Patents provide moats, but powerful brand names are just as good—often better, in fact, because they persist. No one but Hermès can make a Hermès handbag, just as Rolex is renowned for its posh timepieces. Sure, they can be copied illegally, but other rich people—the audience that retail buyers most want to impress—know the real thing.

The largest of the luxury-goods firms is a marvel: LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (LVMUY, $89), which, like Hermès and the privately owned fashion giant Chanel, is based in Paris. A conglomerate stitched together by the persuasive Bernard Arnault, who just surpassed Bill Gates as the world’s second-richest person, LVMH has a market capitalization (shares outstanding times stock price) of $220 billion, nearly three times that of Hermès.

LVMH reached a deal in November to purchase one of the few luxury-goods firms not based in Europe: Tiffany (TIF), the 183-year-old jeweler. With the acquisition ($16 billion in cash), Tiffany joins a portfolio of 75 LVMH companies, which, in addition to leather designer Vuitton, champagne maker Moët & Chandon and cognac king Hennessy, includes jewelers Bulgari and Chaumet; fashion houses Christian Dior, Fendi, Givenchy and Loro Piana; plus such odds and ends as the upscale hotel chain Belmond, the business newspaper Les Echos and the famous bubbly Dom Pérignon. LVMH shares have risen 59% in the past 12 months, but the stock’s valuation is not as high-end as you might think: a price-earnings ratio of 24.5, based on consensus profit projections for the year ahead.

When LVMH targets acquisitions, how does it convince the shareholders—many of whom are founding-family members—to sell? First, it offers liquidity, allowing great-grandchildren to cash out, plus economies of scale and management know-how. For example, analysts say that Bulgari has more than doubled sales since being acquired by the conglomerate in 2011.

Smaller versions of LVMH are thriving, too. Kering (PPRUY, $60), also based in Paris, owns such high-fashion brands as Gucci, Bottega Veneta, Yves Saint Laurent, Alexander McQueen and Brioni (whose suits are favored by President Trump). For the nine months ending September 30, Kering revenues rose 17%. The stock trades at a P/E of just under 20 (below that of LVMH) and yields 2% (almost double LVMH’s yield). Compagnie Financière Richemont (CFRUY, $8), based in Bellevue, Switzerland, offers good value, trading well below its 2014 high. Richemont leans toward jewelry and watches, with brands such as Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Piaget, dunhill and Chloé.

More luxe than you think. Don’t be deceived by the name of the Swatch Group (SWGAY, $14). It’s another Swiss collector of luxury brands, including Harry Winston, Omega and Jacquet-Droz, a 261-year-old Swiss watchmaker whose timepieces run well into the tens of thousands of dollars. The stock has fallen 40% since mid 2018 on weak sales, but the problem appears to be temporary, and the stock trades at a low valuation with nearly a 3% yield.

Another smaller, multi-luxury-brand stock is London-based Capri Holdings (CPRI, $37), with a market cap of almost $6 billion. It has three holdings, all strong names: Jimmy Choo, Michael Kors and Versace. But growth lately has disappointed, and the stock took a huge tumble, losing about 65% of its value in the 12-month period through the end of August 2019. It has come back a bit since and trades at a P/E of just 7, based on consensus earnings forecasts for the 12 months ahead.

Want a U.S. company? Tapestry (TPR, $27) is based in trendy Hudson Yards in New York. Its brands—Kate Spade, Coach and Stuart Weitzman—are high-quality but a notch below luxury. Still, the stock, like Capri, may be too attractive to ignore. Shares are down by about half since April 2018 and trade at a P/E of just 10, based on consensus forecasts for the coming 12 months, with a yield of more than 5%.

Other than Hermès, most great individual luxury-goods firms have either been acquired or—like Chanel, Rolex, jeweler Graff and the world’s best menswear designer, the Italian firm Kiton—are private.

There is no need for a luxury-goods mutual fund. Just buy LVMH, Kering or Richemont—or all three—and strongly consider the individual companies and smaller multi-firm stocks as well. If the global economy slows, these companies could suffer and their share prices might fall. In that case, buy more. Developing a new luxury brand is an expensive and time-consuming venture. But you can become a partner in the established ones.

James K. Glassman chairs Glassman Advisory, a public-affairs consulting firm. He does not write about his clients. His most recent book is Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments in a Time of Turbulence. He owns none of the stocks mentioned in this column.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach Retirement

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach RetirementA five-year CD can help you reach other milestones as you approach retirement.

-

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?If your kids are successful, do they need an inheritance? Ask yourself these four questions before passing down another dollar.

-

5 Big Tech Stocks That Are Bargains Now

5 Big Tech Stocks That Are Bargains Nowtech stocks Few corners of Wall Street have been spared from this year's selloff, creating a buying opportunity in some of the most sought-after tech stocks.

-

How to Invest for a Recession

How to Invest for a Recessioninvesting During a recession, dividends are especially important because they give you a cushion even if the stock price falls.

-

10 Stocks to Buy When They're Down

10 Stocks to Buy When They're Downstocks When the market drops sharply, it creates an opportunity to buy quality stocks at a bargain.

-

How Many Stocks Should You Have in Your Portfolio?

How Many Stocks Should You Have in Your Portfolio?stocks It’s been a volatile year for equities. One of the best ways for investors to smooth the ride is with a diverse selection of stocks and stock funds. But diversification can have its own perils.

-

An Urgent Need for Cybersecurity Stocks

An Urgent Need for Cybersecurity Stocksstocks Many cybersecurity stocks are still unprofitable, but what they're selling is an absolute necessity going forward.

-

Why Bonds Belong in Your Portfolio

Why Bonds Belong in Your Portfoliobonds Intermediate rates will probably rise another two or three points in the next few years, making bond yields more attractive.

-

140 Companies That Have Pulled Out of Russia

140 Companies That Have Pulled Out of Russiastocks The list of private businesses announcing partial or full halts to operations in Russia is ballooning, increasing economic pressure on the country.

-

How to Win With Game Stocks

How to Win With Game Stocksstocks Game stocks are the backbone of the metaverse, the "next big thing" in consumer technology.