The Perils of Investing in Index Funds

Index funds have been the stars of the bull market. But investors may get a nasty surprise in the next bear market.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

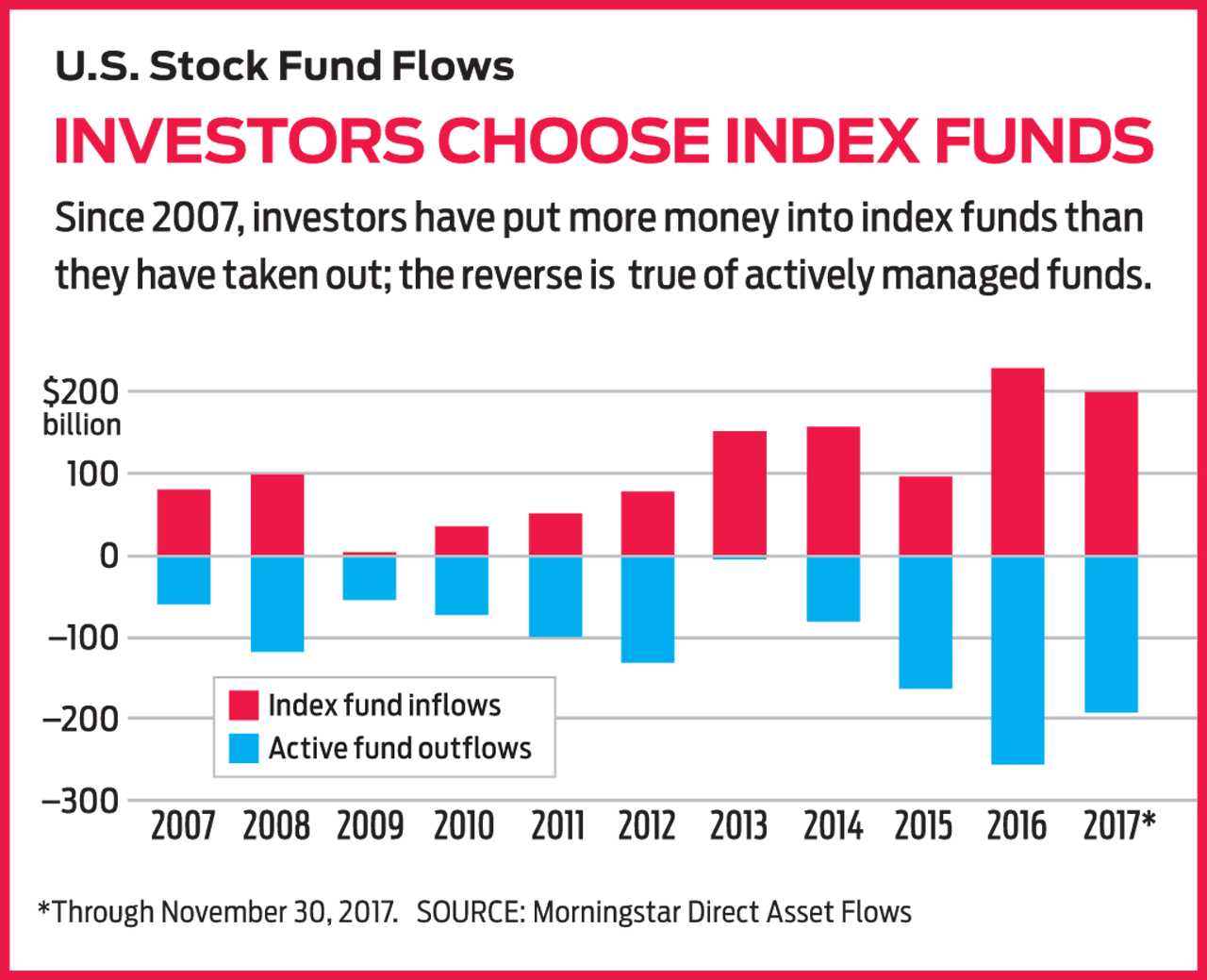

A sea change has been quietly reshaping portfolios in recent years. Investors have been fleeing actively managed funds and flocking to index funds. In 2017 (through November), investors pulled $191 billion from actively managed U.S. stock funds and poured $198 billion into indexed U.S. stock funds, according to Morningstar, the investment research firm. Investors have, on net, withdrawn money from active U.S. stock funds and invested in U.S. stock index funds in every year since 2007. Those investors have likely been chasing strong relative performance among index funds. Not a single category of actively managed funds has managed to beat comparable index funds over the past 10 years through June 2017, according to Morningstar.

But the tide could be turning. Active management staged an impressive comeback in 2017. In the 12 months through June (the most recent period for which data is available), eight out of the 12 actively managed fund categories that Morningstar tracks beat peer index funds. That marked a massive turnaround, given that only one out of the 12 categories of active funds beat similar passive funds in 2016.

Stock pickers get their groove back. Stock correlations—the degree to which individual stocks tend to move together—have been plummeting since 2016. And although most sectors gained in 2017, there was an unusually wide gap in returns between the sectors that performed the best and those that fared worst. That makes for a fertile environment for stock pickers, who can more easily beat an index when fewer stocks and sectors move in lockstep with it.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Of course, a dyed-in-the-wool index investor might not fret about missing out on a slight performance advantage. That, after all, is the basic trade-off of indexing: You forgo any chance of beating the market in exchange for the promise of matching the market, minus fees.

Active funds may shine in down markets in part because managers can keep more cash on hand than do index funds.

But index investors might feel differently if they knew that they could be staring down larger losses than their active-fund counterparts during the next bear market. Fidelity found that active funds that invest in large U.S. companies beat their benchmarks by half a percentage point, on average, during a period roughly coinciding with the 2007–09 bear market. Some active funds trounced the indexes. For example, the bargain-seeking AMG Yacktman fund (symbol YACKX) beat Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index by nearly nine percentage points over the course of the bear market. “By definition, index funds guarantee that you will suffer 100% of the next bear market’s decline,” says Jim Stack, president of InvesTech Research.

Active funds may shine in down markets in part because managers can keep more cash on hand than do index funds. But it’s also likely, if difficult to prove, that managers’ judgment calls deserve credit. Typically, parts of the market turn frothy in the late stages of a bull run (think of the housing and financial sectors before the 2007–09 downturn, or internet stocks before the 2000–02 bust). Active managers might identify excesses and trim the troublesome sectors before stocks turn south.

By contrast, because most indexes weight components by market capitalization (stock price multiplied by shares outstanding), they impose no checks on ballooning, overvalued stocks and sectors, which account for an ever-increasing portion of the index as those assets keep rising. That leaves investors in funds that mirror the index exposed in a falling market, when those overvalued stocks and sectors usually lose the most. Investors worried about holding outsize stakes in pricey assets might note the 11% weighting of FAANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google parent Alphabet) in the S&P 500, or the overall 24% weighting of technology stocks in the index.

Not only might index funds lose more in a bear market, they may also drive investors to make worse decisions when stocks fall. Dalbar, a research and consulting company, tracks what it calls “investor returns.” Unlike traditional return measures, investor returns represent what you actually see on your statement because they take into account buy and sell decisions. You can invest in a top-performing fund, for instance, but if you buy high and sell low, your investor returns won’t measure up to the fund’s return. Dalbar found that investor returns in active funds beat investor returns in index funds by the widest margins during falling markets.

That means investors may do a better job of buying low—and avoiding selling low—in active funds. If an active manager is able to curb fund losses during a bear market, investors may feel more comfortable holding on. And if investors are better able to hold on, then a manager need not sell holdings at fire-sale prices to meet redemptions. That, in turn, boosts performance. “Investor behavior tends to be at its worst when the market is down,” says Cory Clark, director at Dalbar. “That is when something more than just tracking an index can soften the blow.”

Despite the potential advantages of active funds in bear markets, many investors believe that index funds are categorically less risky than actively managed funds. More than half of investors say index funds add more stability to portfolios than actively managed funds, according to Fidelity. “Investors equate index investing with safety,” says Stack. Those investors could be in for a nasty surprise when the long-running bull market eventually falters. Considering historical bear-market losses, Stack says, “When this party does end, investors could be facing a potential 40% loss if they remain fully invested in a blue-chip index fund.”

Index wisely. This is not to say that investors should bail out of index funds. They offer valuable benefits—chiefly lower costs and instant diversification within a given investment category. Just as with any style of management, index funds have strengths and weaknesses, and investors should keep those in mind when deciding how to use indexing in their portfolios.

Index funds that invest in large U.S. companies have a winning long-term track record. But with $2.2 trillion of passive assets already pegged to the S&P 500, investors wary of market distortions should consider broader-based choices, such as Vanguard Total Stock Market (VTSMX) or its exchange-traded cousin (VTI), which is a member of the Kiplinger ETF 20, a list of our recommended exchange-traded funds. Fidelity Total Market (FSTMX) is another good choice. These funds are market-capitalization weighted, meaning investors bear the risk of loading up on the priciest stocks in a soaring market. So consider offsetting them with a proven value-oriented fund, such as Dodge & Cox Stock (DODGX), whose contrarian managers attempt to steer clear of manias. The fund is a member of the Kiplinger 25, a list of our favorite actively managed no-load funds.

Equally weighted index funds, in which each holding accounts for the same portion of the fund, may also better avoid bubbles. The trade-offs with these can be higher costs and greater turnover. One targeted fund that we think is a good buy is Guggenheim S&P 500 Equal Weight Health Care (RYH), an ETF 20 member.

The Vanguard and Fidelity total market funds both include modest exposure to midsize and small companies. Fine-tune your allocation to such companies by adding one or more active funds, such as Kip 25 member T. Rowe Price Small-Cap Value (PRSVX). Consider a similar approach for international stocks: Pick one broad-based index fund as your core holding—say, Vanguard Total International Stock (VGTSX) or the ETF equivalent (VXUS), which is in the Kip ETF 20—and then use actively managed funds to highlight geographic areas or promising investment styles. With bonds, consider sticking mainly to active funds in the current market, in which rising rates and other challenges call for flexibility and nimbleness.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach Retirement

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach RetirementA five-year CD can help you reach other milestones as you approach retirement.

-

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?If your kids are successful, do they need an inheritance? Ask yourself these four questions before passing down another dollar.

-

4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs

4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family NeedsThe key to successful estate planning for HNW families isn't just drafting these four documents, but ensuring they're current and immediately accessible.

-

The 5 Best Actively Managed Fidelity Funds to Buy and Hold

The 5 Best Actively Managed Fidelity Funds to Buy and Holdmutual funds Sometimes it's best to leave the driving to the pros – and these actively managed Fidelity funds do just that, at low costs to boot.

-

The 12 Best Bear Market ETFs to Buy Now

The 12 Best Bear Market ETFs to Buy NowETFs Investors who are fearful about the more uncertainty in the new year can find plenty of protection among these bear market ETFs.

-

Don't Give Up on the Eurozone

Don't Give Up on the Eurozonemutual funds As Europe’s economy (and stock markets) wobble, Janus Henderson European Focus Fund (HFETX) keeps its footing with a focus on large Europe-based multinationals.

-

Vanguard Global ESG Select Stock Profits from ESG Leaders

Vanguard Global ESG Select Stock Profits from ESG Leadersmutual funds Vanguard Global ESG Select Stock (VEIGX) favors firms with high standards for their businesses.

-

Kip ETF 20: What's In, What's Out and Why

Kip ETF 20: What's In, What's Out and WhyKip ETF 20 The broad market has taken a major hit so far in 2022, sparking some tactical changes to Kiplinger's lineup of the best low-cost ETFs.

-

ETFs Are Now Mainstream. Here's Why They're So Appealing.

ETFs Are Now Mainstream. Here's Why They're So Appealing.Investing for Income ETFs offer investors broad diversification to their portfolios and at low costs to boot.

-

Do You Have Gun Stocks in Your Funds?

Do You Have Gun Stocks in Your Funds?ESG Investors looking to make changes amid gun violence can easily divest from gun stocks ... though it's trickier if they own them through funds.

-

How to Choose a Mutual Fund

How to Choose a Mutual Fundmutual funds Investors wanting to build a portfolio will have no shortage of mutual funds at their disposal. And that's one of the biggest problems in choosing just one or two.