5 Key Financial Aid Considerations When Saving for College

Get real about what you might need to pay for your child's education.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Parents of young children see a lot advice about saving for college. Trying to save for the full sticker price can be daunting — even for an in-state public school. For most people, it makes sense to consider how much financial aid your family might receive when developing a savings strategy.

The key is to be realistic. Rules of thumb might be useful, but they could also be inappropriate for your situation. And whatever you do, don’t let the quest for financial aid eligibility deter you from saving.

When factoring financial aid into your estimate of the savings you will need, consider these five points.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

1. Colleges probably expect you to pay more than you think you can afford.

The government and most colleges award financial aid based on your FAFSA, the Free Application for Federal Student Aid. Your FAFSA determines your Expected Family Contribution, or EFC. The EFC depends on many factors, but the most important is your family income. If your EFC is less than a college’s cost of attendance, the difference is considered your “need.”

We calculated the EFC for dual-income families of four with one child in college.

For example, a hypothetical family earning $120,000 with $50,000 saved in 529 college savings accounts (or other non-retirement accounts) has an EFC of $24,802. At a private college costing $60,000 per year, this family would have $35,198 of need. At an in-state public college with a $22,000 cost, their need is zero.

For a Family of Four with One Child in College, 2019-20 School Year:

Estimated Expected Family Contribution ($)

| Parents' 2017 Adjusted Gross Income ($) | Total current value of parents' cash and non-retirement investments ($) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | 25,000 | 50,000 | 75,000 | 100,000 | 125,000 | 150,000 | 175,000 | 200,000 | |

| 60,000 | 4,826 | 5,201 | 5,991 | 6,861 | 7,866 | 8,976 | 10,190 | 11,600 | 13,010 |

| 80,000 | 9,524 | 10,129 | 11,539 | 12,949 | 14,359 | 15,769 | 17,179 | 18,589 | 19,999 |

| 100,000 | 16,413 | 17,118 | 18,528 | 19,938 | 21,348 | 22,758 | 24,168 | 25,578 | 26,988 |

| 120,000 | 22,687 | 23,392 | 24,802 | 26,212 | 27,622 | 29,032 | 30,442 | 31,852 | 33,262 |

| 140,000 | 28,736 | 29,441 | 30,851 | 32,261 | 33,671 | 35,081 | 36,491 | 37,901 | 39,311 |

| 160,000 | 34,785 | 35,490 | 36,900 | 38,310 | 39,720 | 41,130 | 42,540 | 43,950 | 45,360 |

| 180,000 | 40,834 | 41,539 | 42,949 | 44,359 | 45,769 | 47,179 | 48,589 | 49,999 | 51,409 |

| 200,000 | 46,629 | 47,334 | 48,744 | 50,154 | 51,564 | 52,974 | 54,384 | 55,794 | 57,204 |

| 220,000 | 52,396 | 53,101 | 54,511 | 55,921 | 57,331 | 58,741 | 60,151 | 61,561 | 62,971 |

| 240,000 | 58,163 | 58,868 | 60,278 | 61,688 | 63,098 | 64,508 | 65,918 | 67,328 | 68,738 |

| 260,000 | 64,093 | 64,798 | 66,208 | 67,618 | 69,028 | 70,438 | 71,848 | 73,258 | 74,668 |

| 280,000 | 70,025 | 70,730 | 72,140 | 73,550 | 74,960 | 76,370 | 77,780 | 79,190 | 80,600 |

| 300,000 | 75,905 | 76,610 | 78,020 | 79,430 | 80,840 | 82,250 | 83,660 | 85,070 | 86,480 |

The table shows EFC based on family income on the left, and certain assets at the top. Those assets can include cash, stocks, bonds, mutual funds and other investments, as well as the value of real estate other than your primary home and any business ownership. It excludes retirement accounts (such as an IRA or 401(k)), but 529 college savings accounts are included. Assumptions that affect EFC: The older parent is 50 years old as of 12/31/19. The student is a dependent, has $5,000 of assets and has income below $6,500. The family has no non-work income or other assets for FAFSA purposes. The family uses the married filing jointly status and standard deduction for federal income tax and lives in a state with the median FAFSA tax allowance.

Source: T. Rowe Price calculations based on The EFC Formula

A few key takeaways from these calculations:

- The EFC calculation “expects” you to devote a major chunk of your income to college.

- Accumulating more assets doesn’t increase your EFC nearly as much as increasing your income. Some assets are excluded from the calculation--the amount depends on your age — and at most, only 5.64% of additional assets are added to the EFC. Additional income, on the other hand, can increase your EFC by as much as 47%.

For most people, especially high earners, maximizing financial aid is a bad excuse for not saving.

On a happier note, if you have two kids in college at the same time, it can cut your EFC for each by nearly half — but only in years they overlap in college. This is something to consider in your calculations.

2. Even if you have “need,” colleges may not give you that amount of financial aid.

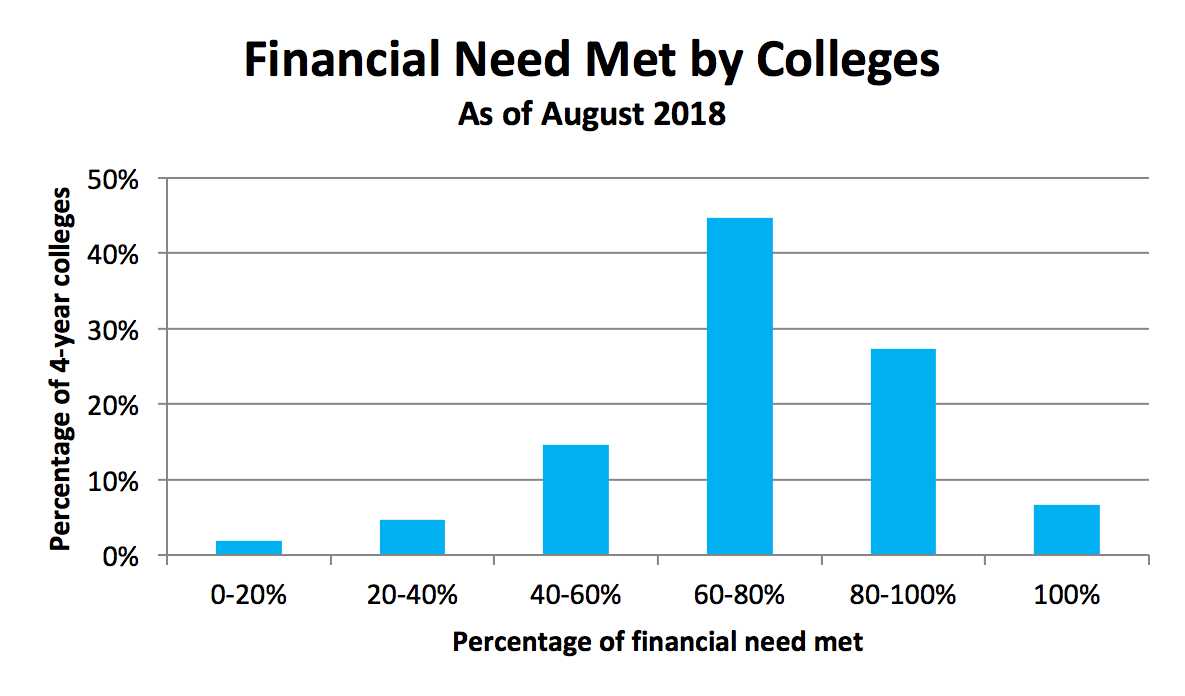

Fewer than 10% of four-year colleges meet 100% of their students’ demonstrated financial need, according to the College Board. Nearly half meet between 60% and 80%. And even at a school that meets a high percentage, it can vary widely from student to student. Be conservative in estimating how much need-based aid your family can receive.

Source: T. Rowe Price calculations based on College Board Big Future college search data

3. That “financial need met” statistic includes loans. That means your aid package is not necessarily “free money” from grants.

Here’s the breakdown of financial aid for undergraduates in 2016-17 from the College Board:

- Grants: 58%

- Federal loans (not including private loans): 32%

- Other: 10%

Loans can be a significant part of the financial aid package, especially for families with significant income. So even if the college offers financial aid equal to your need, your family could still ultimately have to pay more than the EFC.

It’s perfectly reasonable to include loans as part of your college funding strategy. However, we strongly recommend limiting debt to federal student loans, not private loans. For most students, federal loans are currently capped at $27,000 in total for four years of undergraduate education. Parental and private loans generally have less favorable terms and aren’t considered part of the financial aid package.

Don’t assume that saving more will mean you pay more for college. It might just reduce the amount your child can borrow.

4. Your talented child may not receive massive merit or athletic scholarships.

College consultants like to talk about the plethora of scholarship opportunities available from a variety of sources. There certainly are a lot of them, and every bit helps. But many are relatively small compared to the scholarships offered by colleges, which can be very competitive. While some colleges give them as a way to discount tuition, elite schools like the Ivies don’t offer merit scholarships at all. Athletic scholarships are primarily at Division I schools, and for most sports they likely aren’t a full ride.

5. Rely on figures based on your situation instead of hypothetical amounts.

How can you tie all of these factors together and figure out what you should be saving? Good news: There are tools available that can help you estimate the amount you may need to save each month

Using the guidance above to predict your EFC and financial aid potential — and considering your willingness to accept federal loans — can help you input a realistic cost, or percentage of total cost, you’ll need to fund.

To get more specific, another great tool is the online Net Price Calculator (NPC) provided by each college. Just enter your financial data (anonymously, if you wish) and get an estimated financial aid package for that school. This is especially valuable as the college decision approaches before you complete the FAFSA, but parents of younger children can use it to calculate a ballpark estimate. Results from the NPC can then inform your inputs into a savings calculator.

If a calculator suggests what seems to be an unrealistic amount, don’t despair. Save what you can and work toward a plan that enables your child to graduate. When it comes to saving for college, I don’t recall anyone ever telling me they’re unhappy that they saved too much.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Roger Young is Vice President and senior financial planner with T. Rowe Price Associates in Owings Mills, Md. Roger draws upon his previous experience as a financial adviser to share practical insights on retirement and personal finance topics of interest to individuals and advisers. He has master's degrees from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Maryland, as well as a BBA in accounting from Loyola College (Md.).

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're Rich

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're RichSome frugal habits are worth it, no matter what tax bracket you're in.

-

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works Instead

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works InsteadFor retirees with a pension, traditional withdrawal rules could be too restrictive. You need a tailored income plan that is much more flexible and realistic.

-

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look Like

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look LikeThis is when you should be shifting your focus from growing your portfolio to designing an income and tax strategy that aligns your resources with your purpose.

-

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your Stress

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your StressTo be confident about retirement, consider building a safety net by dividing assets into distinct layers and establishing a regular review process. Here's how.

-

The 4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs (Not Just a Will)

The 4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs (Not Just a Will)The key to successful estate planning for HNW families isn't just drafting these four documents, but ensuring they're current and immediately accessible.

-

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)Couples who talk openly about finances, including estate planning, are more likely to head into retirement joyfully. How can you get the conversation going?

-

How to Get the Fair Value for Your Shares When You Are in the Minority Vote on a Sale of Substantially All Corporate Assets

How to Get the Fair Value for Your Shares When You Are in the Minority Vote on a Sale of Substantially All Corporate AssetsWhen a sale of substantially all corporate assets is approved by majority vote, shareholders on the losing side of the vote should understand their rights.

-

How to Add a Pet Trust to Your Estate Plan: Don't Leave Your Best Friend to Chance

How to Add a Pet Trust to Your Estate Plan: Don't Leave Your Best Friend to ChanceAdding a pet trust to your estate plan can ensure your pets are properly looked after when you're no longer able to care for them. This is how to go about it.

-

Want to Avoid Leaving Chaos in Your Wake? Don't Leave Behind an Outdated Estate Plan

Want to Avoid Leaving Chaos in Your Wake? Don't Leave Behind an Outdated Estate PlanAn outdated or incomplete estate plan could cause confusion for those handling your affairs at a difficult time. This guide highlights what to update and when.