How Might Archegos’ $10 Billion in Losses Affect Your Retirement?

Could derivatives cause the next financial crisis like they did in 2008? I’m seeing some very troubling signs.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

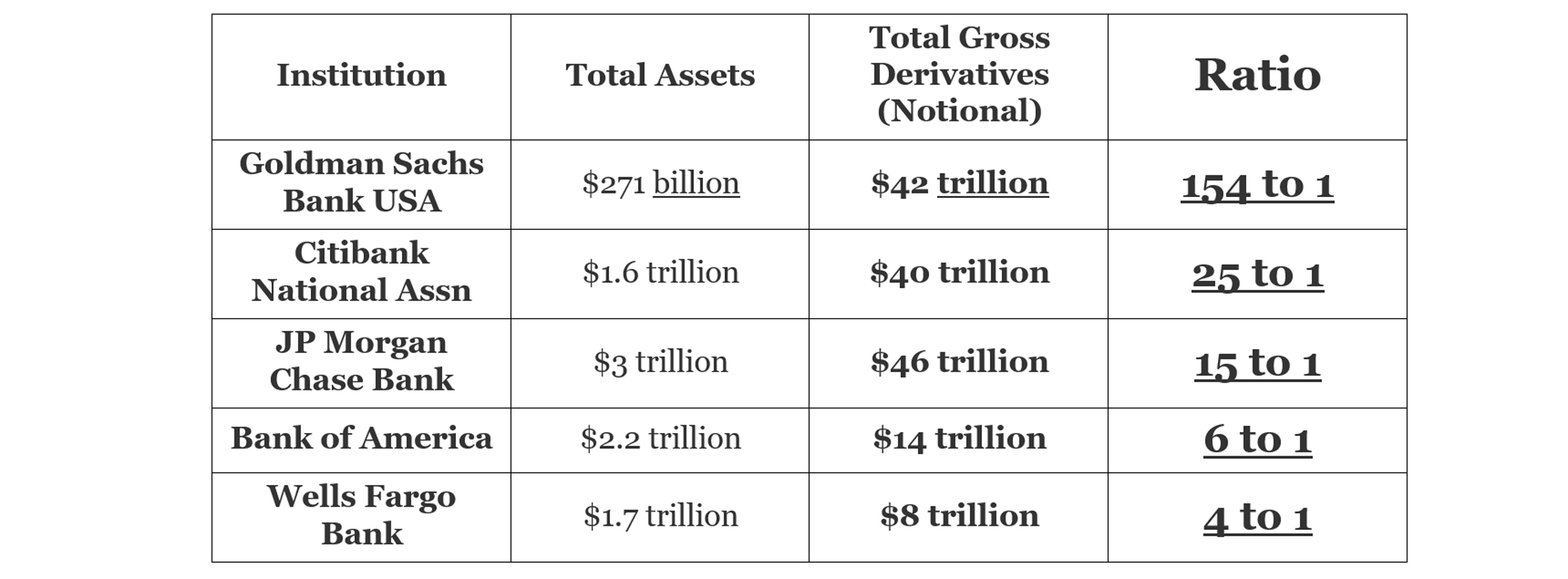

Imagine you walked into a Las Vegas casino and you brought all the money you had, let’s say $1 million, and the casino gave you $154 million to gamble with. How smart do you think that would be for that casino? Well, right now Goldman Sachs Bank USA has 154 times their assets in total gross derivatives!

A number of other giant financial banks are also leveraging up using credit default swaps and similar derivative contracts:

Credit default swaps were at the heart of the financial crisis in 2008 that brought down AIG. The insurance giant AIG had been selling credit default swaps for years, collecting tiny premiums, confident that the mortgage market wouldn’t collapse, and that they’d never have to pay out a claim.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

In 2008, the unthinkable happened: Mortgage markets collapsed — and mortgage lenders went to AIG expecting them to make good on their contracts. AIG didn’t have the cash and couldn’t raise it.

In 2021, non-regulated Archegos caused over $10 billion in losses. Archegos was set up as a family office, away from the oversight of the SEC. As such they were allowed to take tremendous bets by using a derivative called a swap, which were bets on stocks using high leverage. Unfortunately, when those stocks went down, massive losses ensued. It is believed that Archegos had $10 billion in assets, yet was allowed to bet on $50 billion to $100 billion of stocks! 5 to 10 times leverage spread out among a number of banks that took losses during March of 2021.

Even Goldman Sachs, which originally wouldn’t do business with Archegos because the founder pleaded guilty to insider trading in 2012, changed their mind and thus was one of the banks that sold stocks in March 2021 to get out of those swap positions with Archegos. It’s estimated that Archegos caused over $10 billion in losses at those banks, not to mention the tremendous drop certain stocks took when the stock selling occurred.

Derivatives Caused the Bankruptcy of Orange County, Calif., in 1994

This bankruptcy happened the way they always do: Slowly at first … and then all at once. In 1994, Orange County, Calif., suddenly went bankrupt. It was the biggest municipal bankruptcy in history at the time, and for almost two decades after that.

How did it happen? The county was struggling to fund basic services and was desperate to find ways to increase returns on its portfolio. Treasurer Robert Citron turned to derivatives — and massive amounts of leverage — for help to increase their returns.

The county got caught short when interest rates turned against them in 1994. When Wall Street refused to roll their short-term loans over, they were forced to realize the losses. The county lost over $1.6 billion much of it as a direct result of its ill-advised speculation in derivatives.

Without access to credit markets, cities and local agencies might have trouble making their own obligations.

In 1998, just a few years later, we saw the spectacular collapse of Long-Term Capital Management — another massively leveraged project that speculated in derivatives.

Fast forward to today.

Germany’s financial giant Deutsche Bank is once again ramping up its exposure to a specific type of derivative called credit default swaps. As of the summer of 2019, the total notional gross exposure of these contracts on Deutsche’s books amounted to $53.5 trillion, though the bank is currently looking to slowly unwind its exposure. These contracts provide a ready way for lenders to insure themselves against the risk of default. But unless managed carefully, issuing or buying too many of these swaps can leave financial institutions dangerously overexposed to a sudden deterioration in the credit markets.

What’s a Derivative?

A derivative is a financial instrument that derives its value from something else. There’s no underlying asset — it’s simply a contractual agreement for one party to pay another in case something specific happens in the market.

In the case of a credit default swap, or CDS, lender A contracts with insurer B to pay money in the event their borrower C defaults.

CDS contracts basically function as insurance on bonds. A big lender might buy some CDSs to hedge its exposure, or to buy time for it to raise cash to cover the risk of a default. And a big insurance company or bank might sell CDS contracts to collect premium to goose its income and cash flow.

As long as the borrower C doesn’t default, all is well.

Well, black swans (crazy events) occasionally happen. As discussed above, that’s what happened to AIG. In 2008, AIG didn’t have the cash and couldn’t raise it.

That left banks and other mortgage lenders high and dry: If AIG couldn’t honor their credit default swap contracts, they didn’t have the cash to keep operating. And everyone who relied on these banks was in trouble, too.

Berkshire Hathaway Chairman Warren Buffett said that “Every company in the United States was a domino, and those dominos were placed right next to each other. And when they started toppling, everything was in line.” Warren Buffett wisely declined to lend money to Lehman Brothers and AIG to keep them afloat during the crisis.

Money markets froze, as sellers of short-term commercial paper couldn’t find buyers. Contagion threatened to cause a chain reaction that could bring down the economy as we knew it. It was only through concerted Fed and Treasury action that the U.S. was able to contain the damage.

Deutsche Bank pulled out of the derivatives business in 2014 after regulators drove up trading costs. But recent clearing technology innovations have substantially cut the cost of trading these contracts, making the business much more viable. As long as defaults are low, that is.

How Widespread Is Derivatives Exposure?

Deutsche Bank isn’t alone, as shown on the above chart, many banks have large derivative exposure.

The risk is that the failure of one large buyer or seller of these contracts could cause contagion: A rapid, cascading effect that could take down one financial giant after another in quick succession. In some worst-case scenarios, the chain reaction of failures could overwhelm central banks and their ability to hold back the damage.

Now, the good news is that these massive notional exposures are just that: Notional. You have to net out assets against liabilities: If you have $100,000 in the bank, and you owe a $100,000 loan, you don’t have a notional exposure of $200,000. You have a net zero exposure.

Likewise with credit default swaps and other kinds of derivatives, you have to net the long positions against the short positions. According to the U.S. government, the fact is that the overall “net current credit exposure” is only $507 billion when they net out all of the derivatives among all of the U.S. institutions. Not exactly chump change, but in theory, it’s within the capacity of the capital markets to absorb.

That said, theory and reality are two different things. The danger of a general derivative-fueled crisis isn’t so much because of the raw value of the exposure. The real danger is counterparty risk: Where one seller that didn’t sufficiently balance its long and short positions gets caught in a cash crunch … and cannot cover its promises to others.

Most institutions that get involved in derivatives look to balance out their exposure. They are both buyers and sellers of CDSs, looking for opportunities for price arbitrage, and finding ways to hedge their exposure by getting collateral from their counterparties.

AIG collapsed in 2008 because it didn’t do this. It made the same mistakes in the 2000s that Orange County made in the 1990s. Instead of using CDSs as a risk-reduction tool as they were intended, it used them as a speculative one. In AIG’s case, they always sold coverage, and never bought it. After all, like any insurance contract, in order to earn the premium, all they had to do was provide a promise. It was free money —until the music stopped.

And when it stopped, AIG was caught with a pile of naked CDS promises it had sold that was worth half a trillion dollars: $300 billion to CDS buyers in the U.S. and $200 billion in Europe.

Goldman Sachs Bank USA will probably tell you not to worry because their “total credit exposure from all contracts” is only $116 billion when you net out the derivatives they hold with other banks.

And they are correct that the danger isn’t in the gross value — or even in the overall net exposure. Net exposures are not that high. The real dangers are as follows:

- Greed. The temptation to speculate in these highly leveraged positions, rather than use them as risk management devices. AIG got addicted to the small but steady stream of premiums that they mistook as profits, ignoring the danger of the massive liability accumulating on their books for years. And at Lehman Brothers, senior management started overruling risk management professionals.

- Incompetence. The people running Orange County didn’t mean to go bankrupt. They just didn’t understand what they were getting into. And they dragged a number of cities and local pension funds with them.

- The lure of false accounting. Derivatives are complex — sometimes too complex for regulators and the investment community to understand, outside of a few specialists. To crooks, that’s a feature, not a bug.

- Counterparty risk. See, it doesn’t matter if you think your derivative position is totally balanced and nets out to zero. Because when you have a major bond issuer in your portfolio go belly up and you reach out to the next AIG, expecting them to wire the cash they promised, and they can’t do it, you really weren’t balanced at all. And when you fail, two of your own CDS buyers may be counting on you to meet your obligations the next day. And when you fail, they fail. But they have customers, too. And so on.

For example, Deutsche Bank was having substantial financial problems in 2020. Their stock has plummeted 90% from its 2007 price and they posted a huge loss for 2019. Yet they have $53.5 trillion in gross derivate exposure.

And then it might get worse. When every bank has a significant portfolio of derivatives without much transparency, and every bank has counterparty risk, no bank can risk doing business with any other. Which means the next time we have a major financial challenge, even a healthy bank might not want to buy the commercial paper from another bank, and this commercial paper market is what makes the entire financial world move. This nearly happened after Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, causing a run on money markets as even institutions got spooked.

When a crisis hits, things get very ugly very fast. Like Orange County’s bankruptcy, the crisis on Wall Street happened slowly at first — and then all at once. This is what Ben Bernanke and the Federal Reserve, Hank Paulson and the Treasury Department and President George Bush were facing over that fateful weekend in September of 2008 when they had to bail out the financial system.

So it’s true on the surface theoretical level that it’s not the gross exposure to credit default swaps that matters. It’s the net exposure. But it’s also true that if just one weak link in the chain happens to get caught short, like AIG, it doesn’t matter. The rapid-fire chain reaction that can occur is unpredictable but could still be devastating — even if almost everybody thinks they did a good job netting out CDS sales and purchases.

The Bottom Line

No, you don’t have to panic about the total notional value of the derivatives market. We aren’t going to lose 10 times the total global economy.

But we could still see massive disruption, so diversification matters. And it’s important to help protect yourself. At this time, if you are in or near retirement you might want to get a second opinion on your current retirement plan with a financial advisor that follows the fiduciary standard. Make sure you have the right investment mix for a diversified portfolio that has the right amount of risk for you.

Investment advisory services offered only by duly registered individuals through AE Wealth Management, LLC (AEWM). AEWM and Stuart Estate Planning Wealth Advisors are not affiliated companies. Stuart Estate Planning Wealth Advisors is an independent financial services firm that creates retirement strategies using a variety of investment and insurance products. Neither the firm nor its representatives may give tax or legal advice. Investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal. No investment strategy can guarantee a profit or protect against loss in periods of declining values. Any references to protection benefits or lifetime income generally refer to fixed insurance products, never securities or investment products. Insurance and annuity product guarantees are backed by the financial strength and claims-paying ability of the issuing insurance company. Any media logos and/or trademarks contained herein are the property of their respective owners and no endorsement by those owners of Craig Kirsner or Stuart Estate Planning Wealth Advisors is stated or implied. Our firm is not affiliated with or endorsed by the U.S. government or any governmental agency. The information and opinions contained herein provided by third parties have been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed by Stuart Estate Planning Wealth Advisors. 874208 – 4/21

The appearances in Kiplinger were obtained through a PR program. The columnist received assistance from a public relations firm in preparing this piece for submission to Kiplinger.com. Kiplinger was not compensated in any way.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Craig Kirsner, MBA, is a nationally recognized author, speaker and retirement planner, whom you may have seen on Kiplinger, Fidelity.com, Nasdaq.com, AT&T, Yahoo Finance, MSN Money, CBS, ABC, NBC, FOX, and many other places. He is an Investment Adviser Representative who has passed the Series 63 and 65 securities exams and has been a licensed insurance agent for 25 years.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayAnother worrying bout of late-session weakness couldn't take down the main equity indexes on Wednesday.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

Social Security Break-Even Math Is Helpful, But Don't Let It Dictate When You'll File

Social Security Break-Even Math Is Helpful, But Don't Let It Dictate When You'll FileYour Social Security break-even age tells you how long you'd need to live for delaying to pay off, but shouldn't be the sole basis for deciding when to claim.

-

I'm an Opportunity Zone Pro: This Is How to Deliver Roth-Like Tax-Free Growth (Without Contribution Limits)

I'm an Opportunity Zone Pro: This Is How to Deliver Roth-Like Tax-Free Growth (Without Contribution Limits)Investors who combine Roth IRAs, the gold standard of tax-free savings, with qualified opportunity funds could enjoy decades of tax-free growth.

-

One of the Most Powerful Wealth-Building Moves a Woman Can Make: A Midcareer Pivot

One of the Most Powerful Wealth-Building Moves a Woman Can Make: A Midcareer PivotIf it feels like you can't sustain what you're doing for the next 20 years, it's time for an honest look at what's draining you and what energizes you.

-

I'm a Wealth Adviser Obsessed With Mahjong: Here Are 8 Ways It Can Teach Us How to Manage Our Money

I'm a Wealth Adviser Obsessed With Mahjong: Here Are 8 Ways It Can Teach Us How to Manage Our MoneyThis increasingly popular Chinese game can teach us not only how to help manage our money but also how important it is to connect with other people.

-

Looking for a Financial Book That Won't Put Your Young Adult to Sleep? This One Makes 'Cents'

Looking for a Financial Book That Won't Put Your Young Adult to Sleep? This One Makes 'Cents'"Wealth Your Way" by Cosmo DeStefano offers a highly accessible guide for young adults and their parents on building wealth through simple, consistent habits.

-

Global Uncertainty Has Investors Running Scared: This Is How Advisers Can Reassure Them

Global Uncertainty Has Investors Running Scared: This Is How Advisers Can Reassure ThemHow can advisers reassure clients nervous about their plans in an increasingly complex and rapidly changing world? This conversational framework provides the key.

-

I'm a Real Estate Investing Pro: This Is How to Use 1031 Exchanges to Scale Up Your Real Estate Empire

I'm a Real Estate Investing Pro: This Is How to Use 1031 Exchanges to Scale Up Your Real Estate EmpireSmall rental properties can be excellent investments, but you can use 1031 exchanges to transition to commercial real estate for bigger wealth-building.

-

Should You Jump on the Roth Conversion Bandwagon? A Financial Adviser Weighs In

Should You Jump on the Roth Conversion Bandwagon? A Financial Adviser Weighs InRoth conversions are all the rage, but what works well for one household can cause financial strain for another. This is what you should consider before moving ahead.