Timely Strategies to Protect Your Portfolio

Now is the time to dial back on risk and protect your bull market gains.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

“Set it and forget it” has been an elegantly simple—and lucrative—investment plan for the past nine years. The U.S. economy has rolled along, the stock market has soared, and interest rates, though rising since 2015, remain historically low. Just sitting still with a well-diversified portfolio has worked very well for many investors.

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices

It’s a different story for people in their fifties and older. The day when you’ll need to draw down your nest egg to live on is coming into focus, though it may still be years away. You may not be able to risk a substantial drop in your portfolio’s value because you have less time to wait for it to recover, compared with younger investors. Say you’d bought the S&P 500 at its peak in 2007. You would have been in the hole for more than five years.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

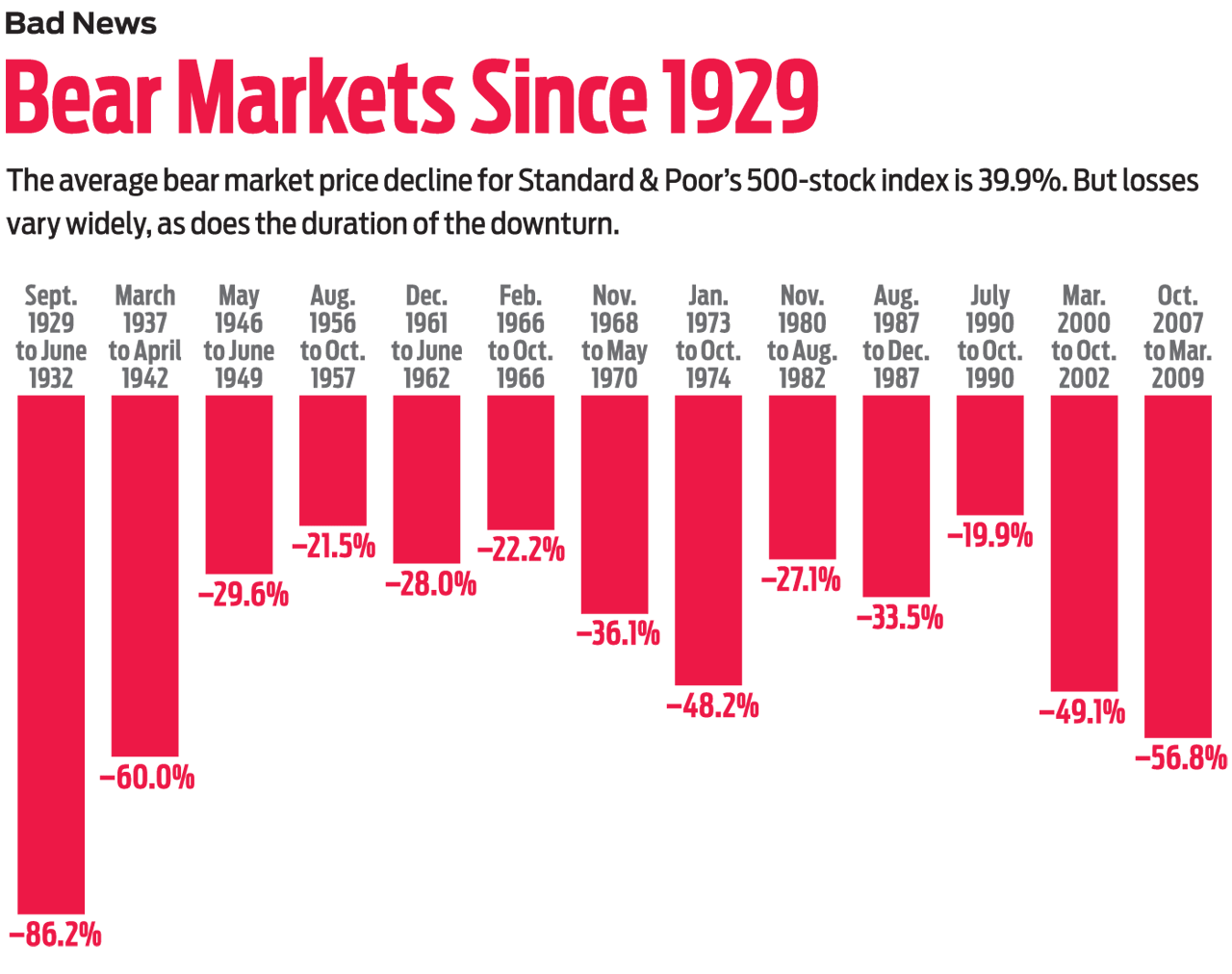

From 1929 through 2009, the S&P 500 experienced 13 bear markets, defined as declines of 20% or more. The average loss was just a tick less than 40%—but the drops ranged from 20% to 86%. “You need to ask, What would a big market decline do to me?,” says Christine Benz, personal finance director at Morningstar. There are two aspects to that question. The first is how a plunge in your portfolio’s value would affect your finances. The other is how it would affect you psychologically. Your risk capacity—the ability to absorb losses without significant harm to your lifestyle—could be high, depending on your age and the size of your nest egg. If your risk tolerance is low, even modest market losses could cause you to panic and make disastrous moves, such as selling everything.

Retune your portfolio

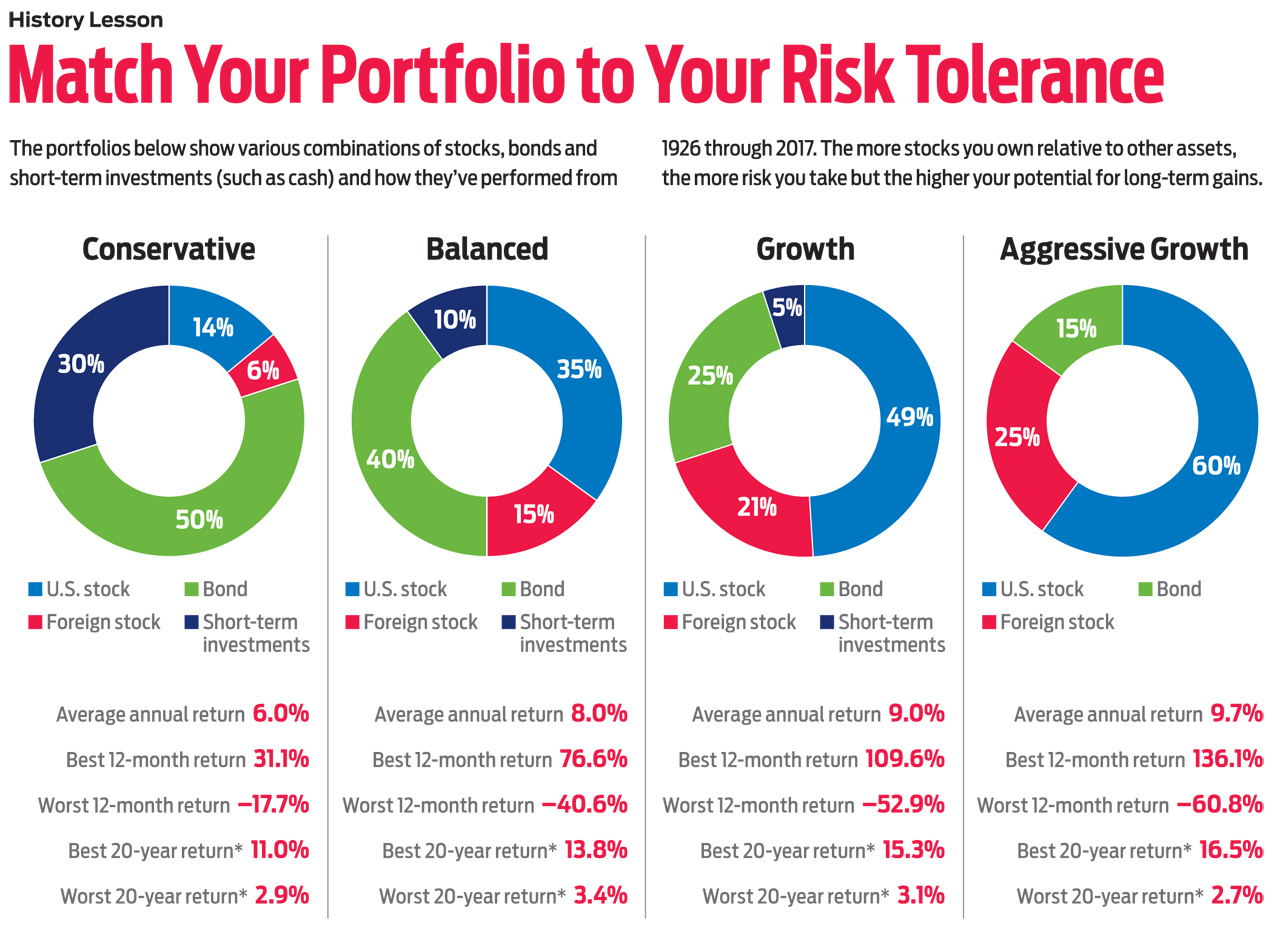

Reconciling risk capacity and risk tolerance is how you get to the most important investing decision: your asset allocation, or how you divide your portfolio among stocks, bonds, cash savings and other investments. Stocks, of course, are among the riskiest and most volatile financial assets. But that also means they often offer the greatest potential returns in the long run. Interest-paying, high-quality bonds have much less risk of drastic short-term losses than stocks; the trade-off is that they offer much lower potential returns. Cash savings, such as bank accounts, have little or no risk, but they offer even lower returns.

Classic asset allocation rules call for young people to keep 80% to 100% of their nest egg in stocks. As you age, the percentage in stocks should decrease, and bond and cash percentages should rise. At age 60, a typical allocation might be 45% stocks, 45% bonds and 10% cash. But your individual mix should depend on your goals and your ability and willingness to handle risk. If you chose a particular mix years ago, it’s important that you review your portfolio now to see whether the allocations have shifted markedly. Given the stock market’s nine-year climb, “an investor who had a stock-to-bond target mix of 65%-35% years ago could now be 80%-20%,” says Wander. That means the portfolio is at much greater risk of loss when stocks eventually stumble.

Fidelity Investments looked at the biggest 12-month losses suffered by different portfolio allocations from 1926 through 2017. The firm found that a portfolio with 85% of assets invested in U.S. and foreign stocks and 15% in bonds lost 61% in its worst 12-month period. If you change the mix to 50% stocks and 50% bonds and cash, the worst-ever loss shrank to 41%.

To keep investment allocations at desired levels, financial advisers say investors should rebalance their portfolios at set intervals, such as once a year, if assets have shifted significantly—say, 5% or more—from the desired target. Trimming assets that have appreciated and reinvesting money in assets that have lost value or risen little is a great way to meet a basic investing goal: to sell high and buy low.

The risk in stocks

The fastest way to cut risk in a portfolio is to reduce stock holdings. The question is, which stocks to reduce? Stock market risk isn’t evenly distributed; some shares are much riskier than others.

Since the market’s low in 2009, the two S&P 500 stock sectors that have risen the most are consumer discretionary (firms that provide nonessential consumer goods or services), which was up 639% through August, and technology, up 565%. Consumer discretionary companies benefit from strong consumer spending—think retailers, homebuilders and entertainment firms. The sector has been powered by household names such as Amazon.com (symbol AMZN), Home Depot (HD), Netflix (NFLX) and Nike (NKE). The tech sector has also been led by giants, including Apple (AAPL), Facebook (FB) and Google’s parent, Alphabet (GOOGL).

After a long bull run, many of these stocks are highly valued relative to earnings and other fundamental measures. Market research firm CFRA in September calculated that the average stock in the S&P 500 was priced at 17 times estimated 2019 earnings per share. But the estimated price-earnings ratio was 22 for consumer discretionary stocks and 19 for technology shares. The higher the valuations, the greater the risk if earnings growth disappoints. Recall that both Facebook and Netflix plunged close to 20% this past summer on concerns about their growth prospects. “It was a good reminder of what can happen” when market stars disappoint, says Wander.

Some market veterans say it’s simply prudent to take profits in the stocks that have racked up the biggest gains. Jim Paulsen, chief investment strategist at research firm Leuthold Group, suggests trimming Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook and Netflix, among others. “Congratulate yourself and let someone else have them,” Paulsen says.

Strategists at Morgan Stanley are warning clients that global economic growth could slow heading into 2019 because of rising interest rates, mounting business costs—such as for raw materials—and trade tensions. The firm sees the tech industry as a likely victim of weaker growth and advises clients to lighten up on the stocks.

But selling winners is one of the hardest decisions for investors, especially when a company’s long-term prospects still seem bright. Bulls say the high prices of tech stocks relative to earnings are justified by their long-term growth outlooks. Yet that was the same argument put forth before the 2000–02 tech-stock crash. After that collapse, Microsoft (MSFT) shares took almost 17 years to get back to their 1999 peak—even though the firm was highly profitable for the entire period. It’s understandable if you can’t bear to part completely with your winners. But at least consider selling a portion of the shares.

Investors whose stock holdings are entirely in exchange-traded funds or conventional mutual funds need to look at what’s in those portfolios to judge how much risk they’re taking and which funds may be ripe for pruning. One surprise may be just how heavily invested you are in technology shares, in both actively managed funds and passive (index) funds, says CFP Wes Shannon at SJK Financial Planning. In the S&P 500, the top four stocks by market value—Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Alphabet—account for an outsize 13% of the entire value of the index. Morningstar’s premium membership ($199 yearly) includes an “x-ray” tool that will tell you the largest holdings in any fund and show your total exposure to any stock across your entire portfolio.

Playing defense

In Wall Street lingo, defensive stocks are ones that are expected to hold up better than the average stock in a broad market sell-off. Those tend to be stocks in slower-growing industries—think utilities, energy firms, financials, drug makers and companies that make consumer staples, such as detergent, toothpaste and packaged foods. Many are considered value stocks because they trade for low prices relative to earnings and other fundamental business measures. Because the shares usually offer fairly modest appreciation potential, they often pay above-average dividends, which increases their appeal to investors when the market slumps.

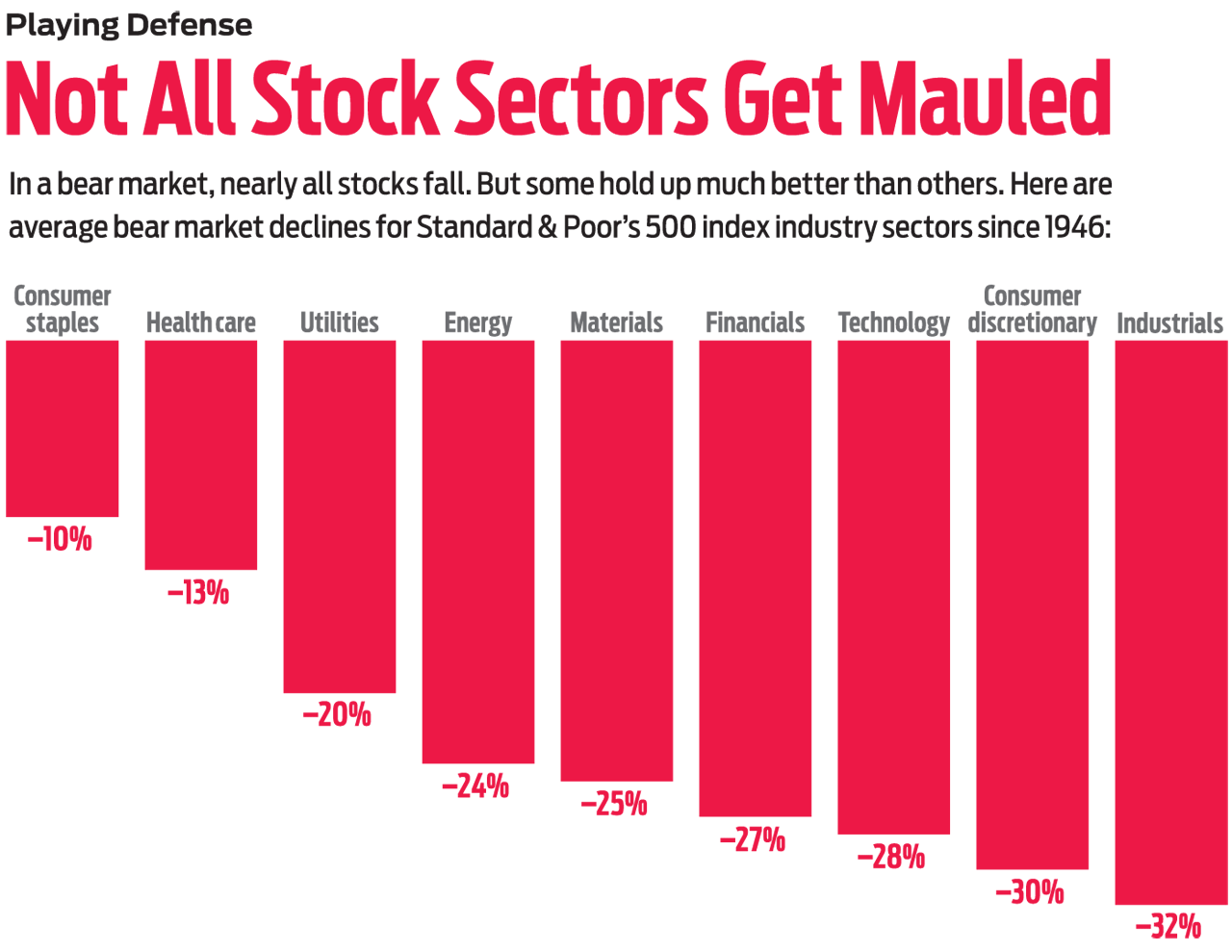

What’s key to remember, though, is that “in a bear market, there is no place to hide,” says Sam Stovall, chief investment strategist at CFRA. “Defensive stocks don’t go up in price in a bear market. They just lose less.”

CFRA looked at stock price moves of major industry sectors in the S&P 500 during the 11 bear markets since 1946. It used month-end prices for sector indexes, which didn’t capture the exact bull market peaks or bear market lows but came close. Using that data, CFRA calculated an average post–World War II bear market loss of 25%. The most defensive sector in those 11 bear periods was consumer staples, which averaged a loss of just 10%. The second-most-defensive sector was health care, with a 13% average loss. Third was utilities, down 20%. Industrial stocks were the biggest losers, down 32% on average. Next was consumer discretionary, down 30%. Tech was off 28%.

Betting on specific industries as a portfolio hedge is easy enough, given the proliferation of low-cost sector index funds. If you like the prospects for banks as interest rates rise, consider Financial Select Sector SPDR ETF (XLF, $28). Another idea: Invesco S&P 500 Equal-Weight Health Care ETF (RYH, $201) is a way to focus on medical-related shares. Both funds are in the Kiplinger ETF 20, the list of our favorite ETFs.

Another defensive option is to add a diversified value-oriented stock fund to your asset mix. Two low-cost, actively managed value funds to consider from the Kiplinger 25, the list of our favorite no-load mutual funds, are Dodge & Cox Stock (DODGX) and T. Rowe Price Value (TRVLX). Indexing fans might look at Vanguard Value ETF (VTV, $112). It owns all the stocks considered value names in the S&P 500.

You might also consider a fund that invests in big-name, dividend-paying stocks. But rather than focusing on current yield, choose a fund that targets companies that raise their dividends every year. The idea is to have a rising income stream over time, even if stock appreciation slows. That could be particularly useful for retirees who will need cash to live on. Vanguard Dividend Appreciation (VIG, $111), a Kip ETF 20 member, targets stocks that have increased dividends every year for at least 10 years. The fund has a current yield of 2.0%. Another good choice is ProShares S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats (NOBL, $68), which invests only in stocks that have raised payouts annually for a minimum of 25 consecutive years. Its current yield is also 2.0%.

A word of caution for dividend fans: Additional Federal Reserve interest rate hikes may push dividend stock prices lower—and their yields higher—because the stocks must compete with rising bond yields. That’s good for yield hunters but painful for share prices in the short run.

Tweaking your bond mix

It’s a frustrating time for bond investors. Measured by total returns—interest earnings plus or minus any change in principal value—most types of bond funds are either in the red—or barely positive for the year so far. The culprit, of course, is the Fed. As it raises short-term interest rates in the strong economy, it drives down the principal value of older fixed-rate bonds and pushes up their yields. That’s part of the logic of rebalancing your portfolio by trimming stocks and buying bonds: You’re taking profits in stocks to pick up higher yields on fixed-income assets. Still, it can be hard to trade a winning investment for one that’s almost certain to come under price pressure.

With the Fed planning more rate hikes in 2019, there are defensive moves you can make with bonds. One is to keep most of your bond allocation in short- or intermediate-term, high-quality bonds rather than in longer-term issues. If market interest rates continue to rise, the shorter a bond’s time to maturity, the smaller the decline in principal value caused by higher rates. The trade-off is that you’ll earn a lower current yield on shorter-term bonds than on longer-term issues. Funds that focus on intermediate-term bonds, which mature in five to 10 years, are a good compromise, and among these it’s hard to beat Dodge & Cox Income (DODIX, yield 3.2%). The actively managed fund’s total return has trounced the average intermediate-term bond fund over the past three, five, 10 and 15 years.

The greatest danger to bonds and stocks alike would be a sudden acceleration in inflation that would force the Fed to hike rates aggressively.

Another defensive move is to shift part of your bond allocation to cash accounts, such as money market mutual funds, which have very low risk of principal loss. The average money fund was recently yielding 1.6%; we like Vanguard Prime Money Market fund (VMMXX), yielding 2.1%.

But nervous investors should fight the urge to hunker down in too much cash. The argument for holding bonds instead of going entirely into greenbacks is twofold. First, if it’s income you need, bonds provide more of it than cash accounts, with the yield on a five-year Treasury note recently 2.9%. The second argument for holding bonds is for insurance: If some calamity were to suddenly rock the economy and the stock market, it’s likely that money would pour into the relative safety of high-quality bonds, pushing prices up and yields down. In the midst of the financial crisis a decade ago, high-quality bonds bucked the downtrend. The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond index returned 5.2% in 2008, compared with a negative 37% total return for the S&P 500.

The greatest danger to bonds and stocks alike would be a sudden acceleration in inflation that would force the Fed to hike rates aggressively, says Bob Doll, chief stock strategist at Nuveen Asset Management. For years, “Low inflation has been financial assets’ best friend,” Doll says. If markets sense that that era is over, “you’d want to own fewer bonds and stocks both.”

One exception: Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS. The principal value of these bonds is guaranteed to rise with inflation. If you don’t own TIPS, this is a good time to buy them, as inflation creeps higher. TIPS are best owned in tax-deferred accounts. Buy them directly from Uncle Sam at www.treasurydirect.gov, or check out Vanguard Inflation-Protected Securities (VIPSX).

An alternative hedge

Investors looking for a buffer in a rough stock market might consider alternative funds. These funds use often-complex strategies aimed at generating returns unrelated to moves in stock and bond markets overall.In general, investors should think of alt funds as a potential portfolio cushion, not a huge moneymaker. Laura Tarbox, a CFP at Tarbox Family Office, uses alternative funds for about 15% of clients’ assets. She doesn’t expect the alt funds to shoot the lights out. “We’re looking for 6% to 8% annual returns, completely uncorrelated” to the stock market, she says.

There are plenty of caveats with these complex investments, including typically high management fees. Some alt funds charge 2% or more annually. Nonetheless, we think some funds are worth considering now. Schwab Hedged Equity (SWHEX), launched in 2002, follows a long/short strategy of buying attractive stocks for gains while also selling unattractive stocks short (selling borrowed shares with the expectation of replacing them at lower prices). Over the past 10 years, the fund has gained 6.2% annualized, compared with 4.7% for the average fund in its category, according to Morningstar.

Options-focused funds seek to profit in part by collecting premiums on stock “put” and “call” option contracts. A put is the right to sell a stock at a preset price by a future date. A call is the right to buy a stock at a preset price by a future date. Investors pay premiums for those rights to investors on the other side of the trades. Glenmede Secured Options (GTSOX) has gained 7.1% a year over the past five years, on average, and has beaten its average peer fund over the past one, three and five years, with a five-year average volatility, or beta, that is less than half that of the stock market overall.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

Nasdaq Slides 1.4% on Big Tech Questions: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Slides 1.4% on Big Tech Questions: Stock Market TodayPalantir Technologies proves at least one publicly traded company can spend a lot of money on AI and make a lot of money on AI.

-

Fed Vibes Lift Stocks, Dow Up 515 Points: Stock Market Today

Fed Vibes Lift Stocks, Dow Up 515 Points: Stock Market TodayIncoming economic data, including the January jobs report, has been delayed again by another federal government shutdown.

-

Stocks Close Down as Gold, Silver Spiral: Stock Market Today

Stocks Close Down as Gold, Silver Spiral: Stock Market TodayA "long-overdue correction" temporarily halted a massive rally in gold and silver, while the Dow took a hit from negative reactions to blue-chip earnings.

-

Nasdaq Drops 172 Points on MSFT AI Spend: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Drops 172 Points on MSFT AI Spend: Stock Market TodayMicrosoft, Meta Platforms and a mid-cap energy stock have a lot to say about the state of the AI revolution today.

-

S&P 500 Tops 7,000, Fed Pauses Rate Cuts: Stock Market Today

S&P 500 Tops 7,000, Fed Pauses Rate Cuts: Stock Market TodayInvestors, traders and speculators will probably have to wait until after Jerome Powell steps down for the next Fed rate cut.

-

S&P 500 Hits New High Before Big Tech Earnings, Fed: Stock Market Today

S&P 500 Hits New High Before Big Tech Earnings, Fed: Stock Market TodayThe tech-heavy Nasdaq also shone in Tuesday's session, while UnitedHealth dragged on the blue-chip Dow Jones Industrial Average.

-

Dow Rises 313 Points to Begin a Big Week: Stock Market Today

Dow Rises 313 Points to Begin a Big Week: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 is within 50 points of crossing 7,000 for the first time, and Papa Dow is lurking just below its own new all-time high.