The Benefits of Working Longer

Delaying retirement for a couple of years—or even a few months—is the most effective way to improve your retirement security.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

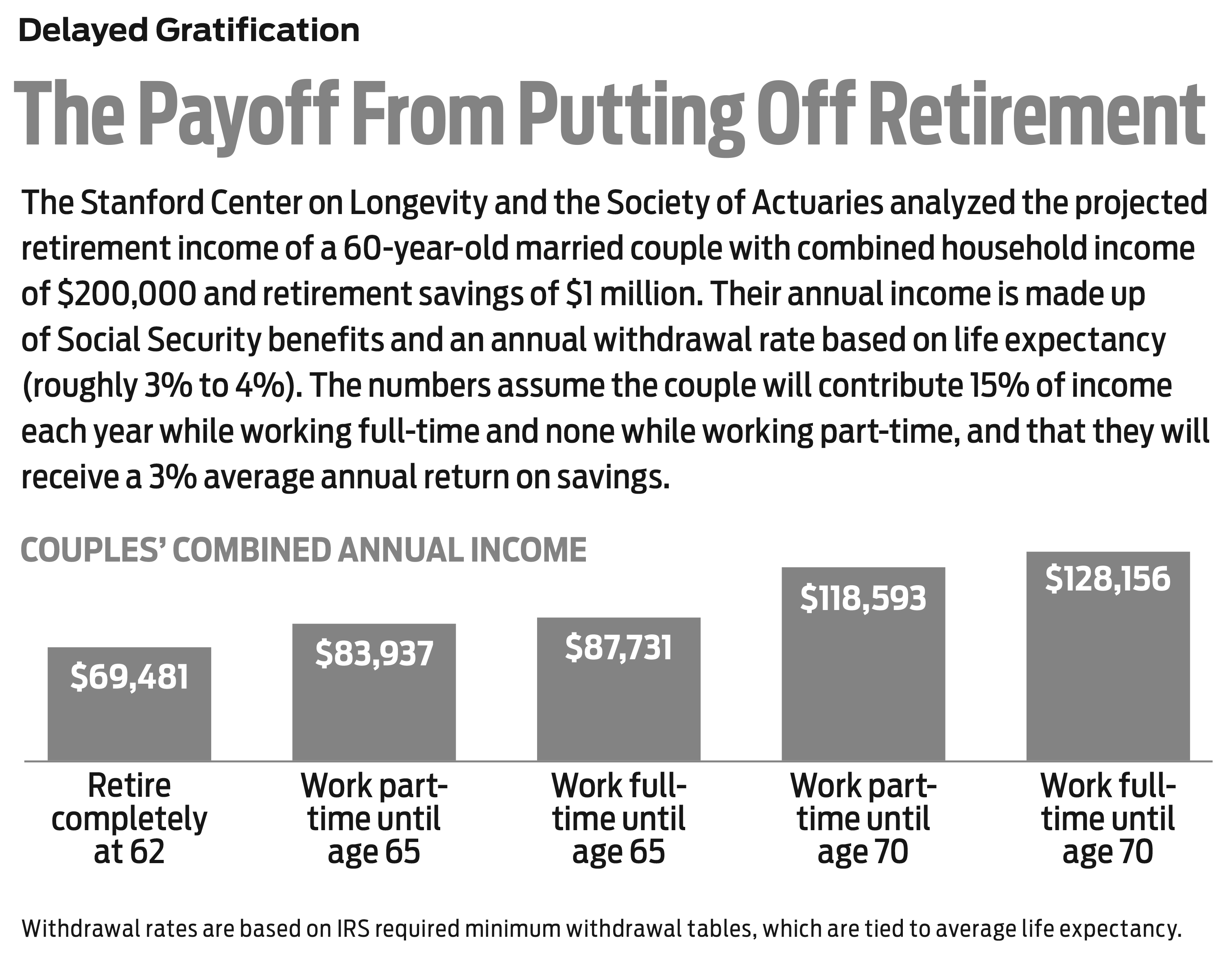

Financial planners and analysts have long advised workers who haven’t saved enough for retirement to work longer. But even if you’ve done everything right—saved the maximum in your retirement plans, lived within your means and stayed out of debt—working a few extra years, even at a reduced salary, could make an enormous difference in the quality of your life in your later years. And given the potential payoff, it’s worth starting to think about how long you plan to continue working—and what you’d like to do—even if you’re a decade or more away from traditional retirement age.

Larry Shagawat, 63, is thinking about retiring from his full-time job, but he’s not ready to stop working. Fortunately, he has a few tricks up his sleeve. Shagawat, who lives in Clifton, N.J., began his career as an actor and a magician. But marriage (to his former magician’s assistant), two children and a mortgage demanded income that was more consistent than the checks he earned as an extra on Law & Order, so he landed a job selling architectural and design products. The position provided his family with a comfortable living.

Now, though, Shagawat is considering stepping back from his high-pressure job so he can pursue roles as a character actor (he’s still a member of the Screen Actors Guild) and perform magic tricks at corporate events. He also has a side gig selling golf products, including a golf cart cigar holder and a vanishing golf ball magic trick, through his website, golfworldnow.com. “I’ll be busier in retirement than I am in my current career,” he says.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Shagawat’s second career offers an opportunity for him to return to his first love, but he’s also motivated by a powerful financial incentive. His brother, Jim Shagawat, a certified financial planner with AdvicePeriod in Paramus, N.J., estimates that if Larry earns just $25,000 a year over the next decade, he’ll increase his retirement savings by $750,000, assuming a 5% annual withdrawal rate and an average 7% annual return on his investments.

Do the math

For every additional year (or even month) you work, you’ll shrink the amount of time in retirement you’ll need to finance with your savings. Meanwhile, you’ll be able to continue to contribute to your nest egg (see below) while giving that money more time to grow. In addition, working longer will allow you to postpone filing for Social Security benefits, which will increase the amount of your payouts.

For every year past your full retirement age (between 66 and 67 for most baby boomers) that you postpone retiring, Social Security will add 8% in delayed-retirement credits, until you reach age 70. Even if you think you won’t live long enough to benefit from the higher payouts, delaying your benefits could provide larger survivor benefits for your spouse. If you file for Social Security at age 70, your spouse’s survivor benefits will be 60% greater than if you file at age 62, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Liz Windisch, a CFP with Aspen Wealth Management in Denver, says working longer is particularly critical for women, who tend to earn less than men over their lifetimes but live longer. The average woman retires at age 63, compared with 65 for the average man, according to the Center for Retirement Research. That may be because many women are younger than their husbands and are encouraged to retire when their husbands stop working. But a woman who retires early could find herself in financial jeopardy if she outlives her husband, because the household’s Social Security benefits will be reduced—and she could lose her husband’s pension income, too, says Andy Baxley, a CFP with The Planning Center in Chicago.

Calculate the cost of health care

Many retirees believe, sometimes erroneously, that they’ll spend less when they stop working. But even if you succeed in cutting costs, health care expenses can throw you a costly curve. Working longer is one way to prevent those costs from decimating your nest egg.

Employer-provided health insurance is almost always less expensive than anything you can buy on your own, and if you’re 65 or older, it may also be cheaper than Medicare. If you work full-time for a company with 20 or more employees, the company is required to offer you the same health insurance provided to all employees, even if you’re older than 65 and eligible for Medicare. Delaying Medicare Part B, which covers doctor and outpatient services, while you’re enrolled in an employer-provided plan can save you a lot of money, particularly if you’re vulnerable to the Medicare high-income surcharge, says Kari Vogt, a CFP and Medicare insurance broker in Columbia, Mo. In 2021, the standard premium for Medicare Part B is $148.50, but seniors subject to the high-income Medicare surcharge will pay $208 to $505 for Medicare Part B, depending on their 2019 modified adjusted gross income. Medicare Part A, which covers hospitalization, generally doesn’t cost anything and can pay for costs that aren’t covered by your company-provided plan.

Vogt recalls working with an older couple whose premiums for an employer-provided plan were just $142 a month, and the deductible was fairly modest. Because of their income levels, they would have paid $1,150 per month for Medicare premiums, a Medicare supplement plan and a prescription drug plan, she says. With that in mind, they decided to stay on the job a few more years.

The math gets trickier if your employer’s plan has a high deductible. But even then, Vogt says, by staying on an employer plan, older workers with high ongoing drug costs could end up paying less than they’d pay for Medicare Part D. “If someone is taking several brand-name drugs, an employer plan is going to cover those drugs at a much better price than Medicare.”

Even if you don’t qualify for group coverage—you’re a part-timer, freelancer or a contract worker, for example—the additional income will help defray the cost of Medicare premiums and other expenses Medicare doesn’t cover. The Fidelity Investments annual Retiree Health Care Cost Estimate projects that the average 65-year-old couple will spend $295,000 on health care costs in retirement.

Long-term care is another threat to your retirement security, even if you have a well-funded nest egg. In 2020, the median cost of a semiprivate room in a nursing home was more than $8,800 a month, according to long-term-care provider Genworth’s annual survey.

If you’re in your fifties or sixties and in good health, it’s difficult to predict whether you’ll need long-term care, but earmarking some of your income from a job for long-term-care insurance or a fund designated for long-term care will give you peace of mind, Baxley says.

And working longer could not only help cover the cost of long-term care but also reduce the risk that you’ll need it in the first place. A long-term study of civil servants in the United Kingdom found that verbal memory, which declines naturally with age, deteriorated 38% faster after individuals retired. Other research suggests that people who continue to work are less likely to experience social isolation, which can contribute to cognitive decline. Research by the Age Friendly Foundation and RetirementJobs.com, a website for job seekers 50 and older, found that more than 60% of older adults surveyed who were still working interacted with at least 10 different people every day, while only 15% of retirees said they spoke to that many people on a daily basis (the study was conducted before the pandemic). Even unpleasant colleagues and a bad boss “are better than social isolation because they provide cognitive challenges that keep the mind active and healthy,” economists Axel Börsch-Supan and Morten Schuth contended in a 2014 article for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

A changing workforce

Many job seekers in their fifties or sixties worry about age discrimination—and the pandemic has exacerbated those concerns. A recent AARP survey found that 61% of older workers who fear losing their job this year believe age is a contributing factor. But that could change as the economy recovers, and trends that emerged during the pandemic could end up benefiting older workers, says Tim Driver, founder of RetirementJobs.com. Some companies plan to allow employees to work remotely indefinitely, a shift that could make staying on the job more attractive for older workers—and make employers more amenable to accommodating their desire for more flexibility. “People who are working longer already wanted to work from home, and this has helped them do that more easily,” Driver says. To make that work, though, older workers need to stay on top of technology, which means they need to be comfortable using Zoom, LinkedIn and other online platforms, he says.

More-flexible arrangements—including remote work—could also benefit older adults who want to continue to earn income but don’t want to work 50 hours a week. Baxley says some of his clients have gradually reduced their hours, from four days a week while they’re in their fifties to three or two days a week as they reach their sixties and seventies.

That assumes, of course, that your employer doesn’t lay you off or waltz you out the door with a buyout offer you don’t think you can refuse. But even then, you don’t necessarily have to stop working. The gig economy offers opportunities for older workers, and you don’t have to drive for Uber to take advantage of this emerging trend. There are numerous companies that will hire professionals in law, accounting, technology and other fields as consultants, says Kathy Kristof, a former Kiplinger columnist and founder of SideHusl.com, a website that reviews and rates online job platforms. Examples include FlexProfessionals, which finds part-time jobs for accountants, sales representatives and others for $25 to $40 an hour, and Wahve, which finds remote jobs for experienced workers in accounting, insurance and human resources (pay varies by experience).

Job seekers in their fifties (or even younger) who want to work into their sixties or later may want to consider an employer’s track record of hiring and retaining older workers when comparing job offers. Companies designated as Certified Age Friendly Employers by the Age Friendly Foundation have been steadily increasing and range from Home Depot to the Boston Red Sox. Driver says age-friendly employers are motivated by a desire for a more diverse workforce—which includes workers of all ages—and the realization that older workers are less likely to leave. Contrary to the assumption that older workers have one foot out the door toward retirement, their turnover rate is one-third of that for younger workers, Driver says.

At the Aquarium of the Pacific, an age-friendly employer based in Long Beach, Calif., employees older than 60 work in a variety of jobs, from guest service ambassadors to positions in the aquarium’s retail operations, says Kathie Nirschl, vice president of human resources (who, at 59, has no plans to retire anytime soon). Many of the aquarium’s visitors are seniors, and having older workers on staff helps the organization connect with them, Nirschl says.

John Rouse, 61, is the aquarium’s vice president of operations, a job that involves everything from facility maintenance to animal husbandry. He estimates that he walks between 12,000 and 13,000 steps a day to monitor the aquarium’s operations.

Rouse says he had originally planned to retire in his early sixties, but he has since revised those plans and now hopes to work until at least 68. He has a daughter in college, which is expensive, and he would like to delay filing for Social Security. Plus, he enjoys spending time at the aquarium with the fish, animals and coworkers. “It’s a great team atmosphere,” he says. “It has kept me young.”

New rules help seniors save

If you’re planning to keep working into your seventies—which is no longer unusual—provisions in the 2019 Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act will make it easier to increase the size of your retirement savings or shield what you’ve saved from taxes.

Among other things, the law eliminated age limits on contributions to an IRA. Previously, you couldn’t contribute to a traditional IRA after age 70½. Now, if you have earned income, you can contribute to a traditional IRA at any age and, if you’re eligible, deduct those contributions. (Roth IRAs, which may be preferable for some savers because qualified withdrawals are tax-free, have never had an age cut-off as long as the contributor has earned income.)

The law also allows part-time workers to contribute to their employer’s 401(k) or other employer-provided retirement plan, which will benefit older workers who want to stay on the job but cut back their hours. The SECURE Act guarantees that workers can contribute to their employer’s 401(k) plan, as long as they’ve worked at least 500 hours a year for the past three years. Previously, employees who had worked less than 1,000 hours the year before were ineligible to participate in their employer’s 401(k) plan.

Delayed RMDs. If you have money in traditional IRAs or other tax-deferred accounts, you can’t leave it there forever. The IRS requires that you take minimum distributions and pay taxes on the money. If you’re still working, that income, combined with required minimum distributions, could push you into a higher tax bracket.

Congress waived RMDs in 2020, but that’s unlikely to happen again this year. Thanks to the SECURE Act, however, you don’t have to start taking them until you’re 72, up from the previous age of 70½. Keep in mind that if you’re still working at age 72, you’re not required to take RMDs from your current employer’s 401(k) plan until you stop working (unless you own at least 5% of the company).

One other note: If you work for yourself, whether as a self-employed business owner, freelancer or contractor, you can significantly increase the size of your savings stash. In 2021, you can contribute up to $58,000 to a solo 401(k), or $64,500 if you’re 50 or older. The actual amount you can contribute will be determined by your self-employment income.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Block joined Kiplinger in June 2012 from USA Today, where she was a reporter and personal finance columnist for more than 15 years. Prior to that, she worked for the Akron Beacon-Journal and Dow Jones Newswires. In 1993, she was a Knight-Bagehot fellow in economics and business journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She has a BA in communications from Bethany College in Bethany, W.Va.

-

Dow Loses 821 Points to Open Nvidia Week: Stock Market Today

Dow Loses 821 Points to Open Nvidia Week: Stock Market TodayU.S. stock market indexes reflect global uncertainty about artificial intelligence and Trump administration trade policy.

-

Nvidia Earnings: Live Updates and Commentary February 2026

Nvidia Earnings: Live Updates and Commentary February 2026Nvidia's earnings event is just days away and Wall Street's attention is zeroed in on the AI bellwether's fourth-quarter results.

-

I Thought My Retirement Was Set — Until I Answered These 3 Questions

I Thought My Retirement Was Set — Until I Answered These 3 QuestionsI'm a retirement writer. Three deceptively simple questions helped me focus my retirement and life priorities.

-

15 Cheapest Small Towns to Live In

15 Cheapest Small Towns to Live InThe cheapest small towns might not be for everyone, but their charms can make them the best places to live for plenty of folks.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits in 2026. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.

-

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026SEP IRA A good option for small business owners, SEP IRAs allow individual annual contributions of as much as $70,000 in 2025, and up to $72,000 in 2026.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026simple IRA For 2026, the SIMPLE IRA contribution limit rises to $17,000, with a $4,000 catch-up for those 50 and over, totaling $21,000.

-

457 Contribution Limits for 2024

457 Contribution Limits for 2024retirement plans State and local government workers can contribute more to their 457 plans in 2024 than in 2023.