How a Stock Trade Actually Works

While trades are now commission-free to most consumers, a lot of money is still being made on penny-level differences in the process.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

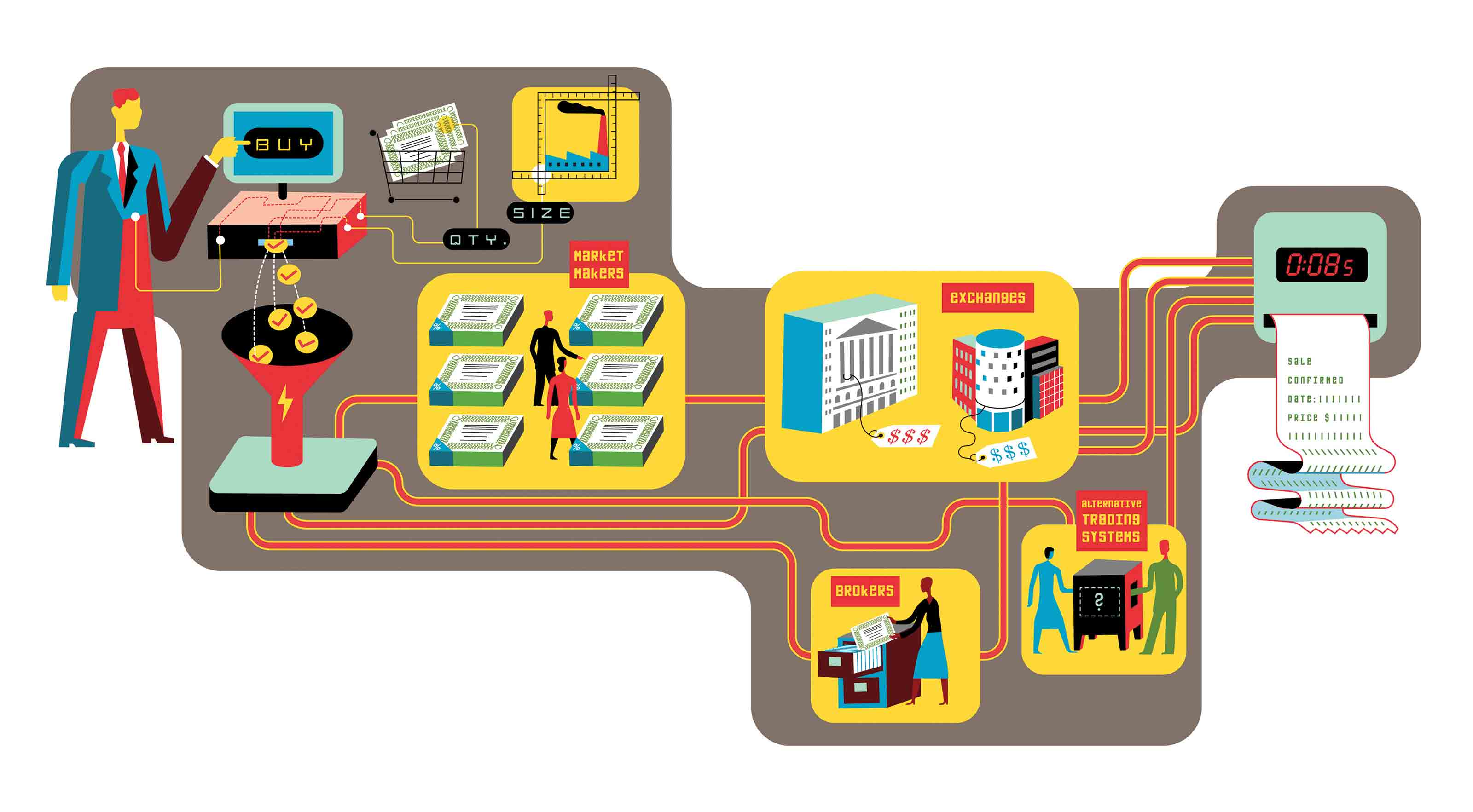

Stock trades are free these days at most online brokers. But where and how your trade is filled can impact your purchase price. And “it all happens in a flash,” says Jeff Chiappetta, vice president of trade and education at Schwab. It takes just 0.08 seconds, on average, at Schwab, from the time you submit your trade to validation of execution. Here’s a step-by-step look at what happens when you place a market-order stock trade.

Step 1: You click “buy”

After you submit a trade but before it is routed to the next step, your brokerage firm will review your trade for certain factors. The size of the company and the size of your trade can influence where and how the order is filled and the price you pay. Fractional orders or oversized orders (say, more than 10,000 shares), for instance, may be filled in multiple transactions. Some firms may scrutinize a trade for whether it could impact the stock’s trading price. An exceptionally large order “could drive the price of a stock up or down,” says Chiappetta, “and we don’t want that.” Some firms also check to see that you have the cash or margin in your account to cover the trade; others may give you leeway to fund the account over the next two business days.

Step 2: Routing

Your broker has a duty to deliver the best possible execution price to you for your trade, which means it must meet or beat the best price available in the market. To do so, it can choose to send your order to one of four venues:

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

■ Market makers, including firms such as Citadel and Virtu Financial, “act like car dealers” for buyers and sellers, says James Angel, a professor at Georgetown’s McDonough School of Business. These firms will pay a fraction of a penny for every share that your broker sends their way in a practice called payment for order flow. Although some brokers don’t accept payment for order flow, it’s not necessarily a bad thing: In exchange for the order flow, the market maker also promises to beat the best quoted price you see flashing on your quote page. Say the current market price for XYZ stock is $50. The market maker may fill your order at $49.98 a share. That’s price improvement.

Brokerages must disclose how much they receive in payment for order flow every year. Firms like to tout their price improvement. Fidelity “passed back $650 million in price improvement” in 2019, says Gregg Murphy, senior vice president of Fidelity’s retail brokerage division. This year, the figure may double. Schwab’s Chiappetta says the firm passes back $8 of price improvement for every $1 it receives for payment for order flow. “Net-net, our clients are saving money,” he says.

■ An exchange, such as Nasdaq or the New York Stock Exchange, can fill the order, too. But the exchanges charge your broker roughly 30 cents for every 100 shares traded, says Angel. “Doesn’t sound like a lot, but every penny adds up,” he adds.

■ Some brokers (but not all) may fill the trade from their own inventory. The broker makes money on the “spread”—the difference between the purchase price and the sale price.

■ Alternative trading systems are a last option. Most trades don’t end up here, says Chiappetta, but these systems match buyers with sellers. In some cases, there’s little transparency. “That’s why they’re called dark pools,” says Chiappetta.

Step 3: Confirmation

You’ll get a notification that the order was filled, at what price and what time. If the order was small (fractional, for example) or oversized (for more than 10,000 shares, say), you might see multiple executions, says Murphy.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Nellie joined Kiplinger in August 2011 after a seven-year stint in Hong Kong. There, she worked for the Wall Street Journal Asia, where as lifestyle editor, she launched and edited Scene Asia, an online guide to food, wine, entertainment and the arts in Asia. Prior to that, she was an editor at Weekend Journal, the Friday lifestyle section of the Wall Street Journal Asia. Kiplinger isn't Nellie's first foray into personal finance: She has also worked at SmartMoney (rising from fact-checker to senior writer), and she was a senior editor at Money.

-

We're 64 with $4.3 million and can't agree on when to retire.

We're 64 with $4.3 million and can't agree on when to retire.I want to retire now and pay for health insurance until we get Medicare. My wife says we should work 10 more months. Who's right?

-

Missed an RMD? How to Avoid That (and the Penalty) Next Time

Missed an RMD? How to Avoid That (and the Penalty) Next TimeIf you miss your RMDs, you could face a hefty fine. Here are four ways to stay on top of your payments — and on the right side of the IRS.

-

What Really Happens in the First 30 Days After Someone Dies

What Really Happens in the First 30 Days After Someone DiesThe administrative requirements following a death move quickly. This is how to ensure your loved ones won't be plunged into chaos during a time of distress.

-

Dow Dives 521 Points as Goldman, AmEx Slide: Stock Market Today

Dow Dives 521 Points as Goldman, AmEx Slide: Stock Market TodayNews of Block's massive layoffs exacerbated AI worries across the financial sector.

-

Big Nvidia Numbers Take Down the Nasdaq: Stock Market Today

Big Nvidia Numbers Take Down the Nasdaq: Stock Market TodayMarkets are struggling to make sense of what the AI revolution means across sectors and industries, and up and down the market-cap scale.

-

Nasdaq Soars Ahead of Nvidia Earnings: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Soars Ahead of Nvidia Earnings: Stock Market TodayWednesday's risk-on session was sparked by strong gains in tech stocks and several crypto-related names.

-

Dow Absorbs Disruptions, Adds 370 Points: Stock Market Today

Dow Absorbs Disruptions, Adds 370 Points: Stock Market TodayInvestors, traders and speculators will hear from President Donald Trump tonight, and then they'll listen to Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang tomorrow.

-

Dow Loses 821 Points to Open Nvidia Week: Stock Market Today

Dow Loses 821 Points to Open Nvidia Week: Stock Market TodayU.S. stock market indexes reflect global uncertainty about artificial intelligence and Trump administration trade policy.

-

Stocks Shrug Off Tariff Ruling, Weak GDP: Stock Market Today

Stocks Shrug Off Tariff Ruling, Weak GDP: Stock Market TodayMarket participants had plenty of news to sift through on Friday, including updates on inflation and economic growth and a key court ruling.

-

Stocks Drop as Iran Worries Ramp Up: Stock Market Today

Stocks Drop as Iran Worries Ramp Up: Stock Market TodayPresident Trump said he will decide within the next 10 days whether or not the U.S. will launch military strikes against Iran.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayAnother worrying bout of late-session weakness couldn't take down the main equity indexes on Wednesday.