Tapping the Power of a Health Savings Account

Health savings accounts help defray the cost of high-deductible health plans. They’re also a powerful way to invest for retirement.

Lower Your Health Care Costs

High-deductible health plans have a well-deserved reputation as a way for employers to pass along some of the burden of spiraling health costs to you. They typically come with lower premiums than traditional insurance plans but require you to pay for more of your medical costs before your insurance kicks in.

Such plans have become more prevalent in recent years. Last year, 30% of people with employer-sponsored health insurance enrolled in high-deductible plans, compared with just 8% a decade earlier, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. For some people, a high-deductible plan may be the only choice offered by their employer.

But high-deductible plans also give you access to a health savings account. And an HSA has secret powers that most people haven’t begun to tap. An HSA isn’t just a short-term, tax-friendly way to pay for current and future medical bills; it’s also a vehicle for supercharging your retirement savings.

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free E-Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

For Marianela Collado, a certified financial planner in Weston, Fla., switching to a high-deductible plan and opening an HSA five years ago was an easy decision. Marianela, her husband, Edgar, and their three boys were healthy and rarely visited the doctor aside from annual checkups. The family began funneling cash into their HSA and covering current medical expenses out of pocket so the account could continue to grow.

Today, Marianela and Edgar, who are both in their early forties, contribute the maximum to their HSA each year, investing most of the money in a portfolio of growth-oriented stocks. "We hope to leave the account untapped for 20 to 30 years so it grows as much as possible," Marianela says. Then, she says, they can use that money for medical expenses during retirement.

Learn the basics. A health savings account offers a tax-saving trifecta. First, contributions to an HSA can be made pretax to an employer-sponsored HSA plan—or they can be deducted (even if you don’t itemize) if you’re saving in an account on your own. Second, money in the account grows tax-deferred. And third, you can take tax-free withdrawals at any time to pay for qualified medical expenses, including deductibles, co-payments, prescription drug costs, and out-of-pocket dental and vision expenses. (If you withdraw the funds for nonqualified expenses before age 65, you’ll pay a 20% penalty, plus income tax on the amount you take out.)

To contribute to an HSA, you must be enrolled in a high-deductible health plan with an annual deductible of at least $1,400 for individual coverage or $2,800 for family coverage in 2020. The plan must also have a limit on out-of-pocket medical expenses including deductibles, co-payments and other amounts (but not premiums). In 2020, the out-of-pocket limit is $6,900 for individual coverage and $13,800 for family coverage.

If your health plan meets those requirements, you can contribute up to $3,550 to an HSA in 2020 if you have individual coverage, or up to $7,100 if you have family coverage, including any cash your employer has kicked in. If you are 55 or older in 2020, you can contribute an additional $1,000 in catch-up contributions.

A couple of other important details: Unlike flexible spending accounts, which generally must be depleted by year-end (or March 15, depending on your employer), HSA funds don’t have a use-it-or-lose-it rule. That means you can build up a stash of tax-free money for major medical bills or for medical expenses much later, such as in retirement. Also, you can't make new contributions to an HSA after Medicare coverage begins, even if you’re still working, but you can continue to use the money that’s already in the account tax-free for eligible costs that aren’t covered by insurance.

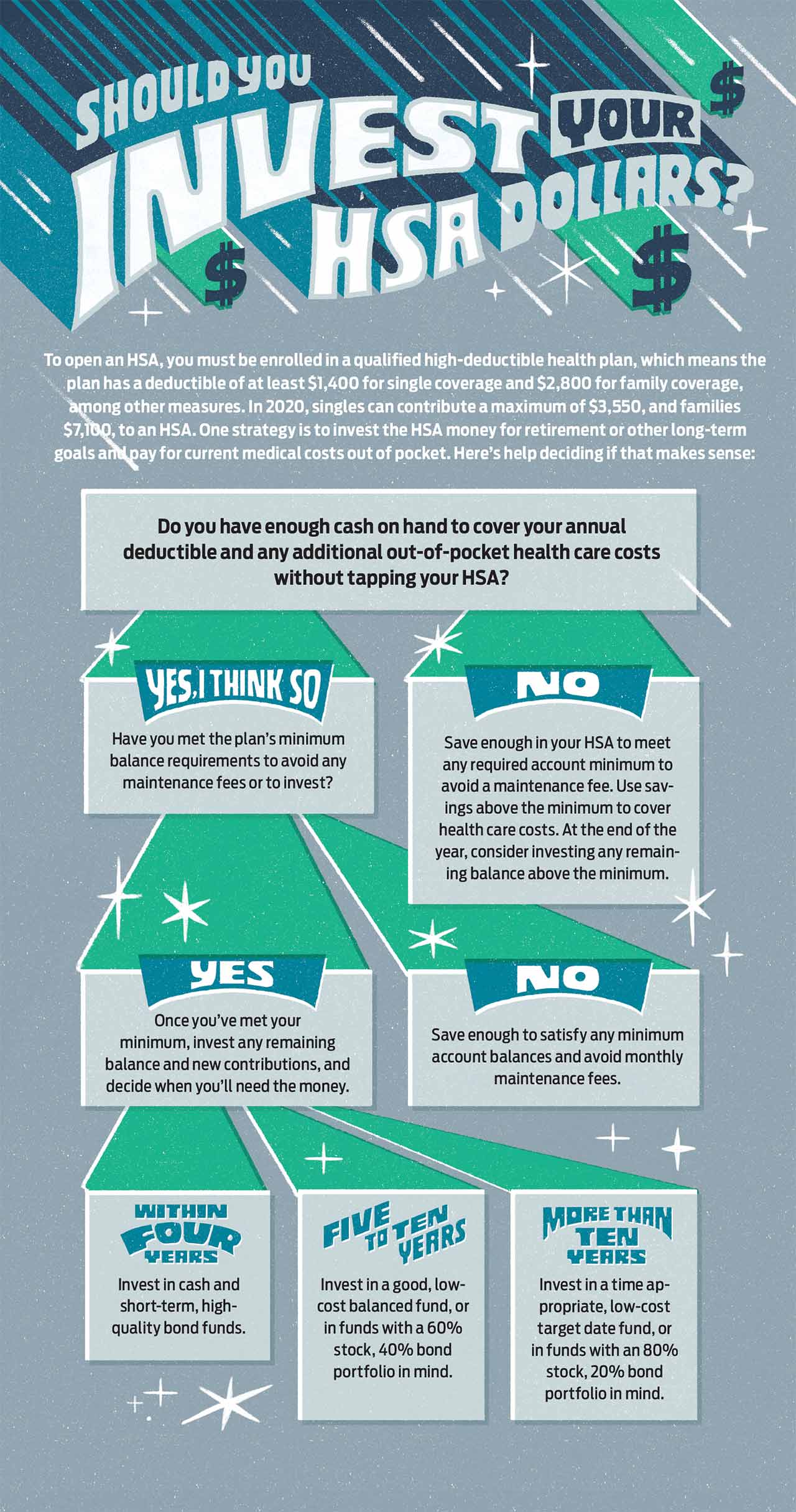

Set your strategy. Before you pledge to invest for the long term in your HSA, check out the decision tree below. The best approach to saving in your HSA depends on how much cash you have available elsewhere to cover out-of-pocket medical expenses, your HSA plan's minimum-balance requirements and how long you think it will be until you need to withdraw the money from the account.

Your decision also hinges on how much you’re saving in your 401(k) or other retirement plans. If you don’t have enough money to max out your HSA and 401(k), start by making sure you’re contributing enough to your 401(k) to get the most out of any match your employer offers. Then, shift your attention to your HSA. If it turns out you're able to save more after hitting the maximum HSA contribution, switch back to saving in your 401(k).

If you have access to an HSA through your employer, that provider’s plan is likely your best bet. Most employers that offer access to an HSA cover the administrative fees. Many also seed the account with a company contribution.

If your employer doesn’t offer an HSA, you don't like the HSA provider your employer uses, or you’re buying health insurance on your own, most banks and brokerage firms offer HSAs to anyone with an eligible policy. You generally won't be able to get an automatic pretax payroll deduction if you open your own account (you can deduct your contributions later), but you may find lower fees and better investing options by switching providers.

To compare fees and expenses along with investing options, visit HSASearch.com. The Collados, for example, will be re-shopping their HSA provider soon. Their current provider has good investing options but requires that $5,000 remain in the checking portion of the account before they may invest. Because the family doesn’t plan to use the money for many years and could cover their full deductible from other sources, they would prefer to invest all of their HSA funds.

Maximizing HSA benefits. You can use the money in your HSA tax-free for eligible medical expenses at any time. But you'll get the most bang for your HSA buck by using other cash for current medical expenses and allowing money in your HSA to grow tax-free.

Save receipts for any out-of-pocket medical expenses that you incur after opening the account. Many health plans and HSA administrators provide online tools to help you track your qualified expenses and record how you paid those bills, making it easier for you to reimburse yourself later.

An HSA can also play a key role in your retirement strategy. You’ll face a stiff penalty (20%, plus income taxes) if you tap your HSA for non-medical expenses before age 65. But after age 65, you’ll only have to pay taxes on the withdrawal if you use it for anything other than eligible medical expenses. Your best bet, though, is to use the money for medical expenses. You can use HSA funds to pay for medical costs that Medicare doesn’t cover, as well as monthly premiums for Medicare Part B and Part D and Medicare Advantage plans. Withdrawals for those costs will be tax- and penalty-free. You can also pay a portion of long-term-care insurance premiums. The amount you can withdraw tax-free depends on your age.

Again, you can't contribute to an HSA after you’re covered under Medicare. But be aware of the tax trap if you delay signing up for Medicare: When you enroll in Part A, you get up to six months of retroactive coverage. To avoid a tax penalty, stop making HSA contributions at least six months before you enroll.

Investing for a Long-Term Goal

If you have enough money to cover your out-of-pocket expenses, use a health savings account to supercharge your retirement savings. But here's the rub: Not all health savings accounts come with an investing option. The big HSA providers, including Bank of America and the HSA Authority, typically do. But HSAs offered through community banks and credit unions don’t, according to HSA consulting firm Devenir. Those accounts are set up primarily for spending.

If your HSA doesn’t have an investment vehicle, don’t worry. You can open a second HSA at a provider that does and add money to that account in tandem with your workplace contributions.

Another alternative is to save only in your workplace HSA but periodically shift money to your investing HSA. "These accounts are portable, unlike money in a 401(k)," says Devenir president Eric Remjeske. The IRS limits taxpayers to one rollover per year from one health savings account to another. But some plans allow direct "trustee to trustee" transfers, which have no annual transaction limit, says Greg Will, a certified public accountant and financial planner in Frederick, Md., because technically, the IRS doesn’t view direct transfers as rollovers.

The tax benefits aren’t exactly the same between employer-sponsored HSAs and an HSA you open up on the side. For one thing, contributions from your paycheck into a workplace account aren't taxed for Social Security and Medicare, which saves you 7.65%, and your contributions are deducted from your paycheck pretax. With a non-workplace HSA, however, you make after-tax contributions. You’re still eligible for a full break on federal, state and local taxes on those contributions, but you don’t collect until you declare them on your tax return.

Shop smart. Finding a good health savings account is tricky, in part because there are hundreds of plans out there. Of the few plans that offer investing capabilities, some feature only mutual funds, and others allow you to invest in stocks, mutual funds and exchange-traded funds. Ben Lake, a financial adviser at Altfest Personal Wealth Management in New York City, has helped some of his clients find and set up an HSA on their own. "It’s kind of tough," he says.

Morningstar, the financial-data firm, rates a handful of the biggest HSA plans every year. Its 2019 report ranks 11 HSA providers on a variety of investing criteria, giving high grades to firms that charge low fees and that offer an appropriate range of high-quality, low-cost, core investment options, among other things.

Fidelity came in first, followed by the HSA Authority and Bank of America. In addition to strong investment options, Fidelity’s HSA plan "charges rock-bottom fees that no other provider can compete with," says Morningstar analyst Leo Acheson, who conducted the HSA study with Megan Pacholok. (Though any stock, ETF or mutual fund is available in Fidelity’s HSA, the firm has a list of good mutual funds it recommends from a variety of firms.) Also, Fidelity allows you to invest with as little as $1 in your Fidelity HSA. By contrast, many HSA providers require a $1,000 to $2,000 balance in your account before you can start investing.

Of course, you can research investing HSAs on your own. The HSA Search tool lets you home in on plans with investing options. The HSA Report Card offers insight into providers that may be suitable for index-fund fans, among other features.

Focus on HSAs with low fees. That includes account fees the provider may levy, as well as the expense ratios of any underlying funds, says Lauren Zangardi Haynes, a certified financial planner in Richmond, Va. “All of these accounts and products are making money somehow. Figure out how they’re doing it and decide if it makes sense for you.”

Follow the investing rules. Approach how you invest your HSA dollars the same way you would any other investment account. Consider your risk tolerance and time frame. "Treat it like a 401(k)," says Maria Bruno, head of Vanguard’s U.S. wealth planning research. The longer your time horizon, the more stocks you can hold in your portfolio. But money you need in less than five years should be socked away in a money market fund or a high-quality short-term bond fund.

For most investors, a good, low-cost target-date fund is a fine choice, no matter how far-off or close you are to retirement. These funds do the work for you, shifting from an aggressive to a more conservative blend of assets over time as you near the target year—in most cases, a year closest to when you plan to retire. The typical target-date fund for savers in their twenties and thirties holds 90% of its assets in stocks; funds for investors in their fifties and early sixties hold between 50% and 60% in stocks and the remainder in bonds.

Even a balanced fund, which holds a static position of 60% stocks and 40% bonds, will work well for most investors with short to medium time frames.

Workers in their twenties, thirties or even forties, who have decades to go before retirement, can afford to spice up their investments. Some financial advisers, including Haynes, the Richmond, Va., financial planner, invest a large portion of younger clients’ HSAs aggressively, in small-company and emerging-markets stock funds. The point is to take advantage of the many tax benefits that come with an HSA and invest for growth so that assets in the account increase as much as possible. "That’s aggressive, but it's balanced with more-conservative investments in other accounts," says Haynes. In fact, most of Haynes's clients keep enough cash in their HSA to cover their annual deductible, even though they don’t plan to use it. "It can supplement a cash emergency fund if a client were to experience very high medical costs," she adds.

That's the other upside to having an HSA. Unlike an IRA or a 401(k), you can access the funds if absolutely necessary without paying a tax penalty. "It’s like having personal hazard insurance," says Lake, the New York City financial adviser. The money is there if you ever experience a serious health care emergency, but ideally you won’t need it and you’ll invest it so it can grow for decades.

Find Good Funds for Your HSA

If an all-in-one mutual fund isn't for you, keep these tips in mind as you search for good funds with strong track records and low costs.

Objective. Figure out your goal, then find a fund that fits. If you can’t afford the losses that come with occasional, but inevitable, down markets, stick with a money market fund or a short-term bond fund. Bond funds tend to be less volatile than stock funds. But depending on what kinds of fixed-income securities they invest in—government bonds, corporate debt or mortgage-backed securities, for example—they will vary in risk, return and volatility. Stock funds offer more growth potential than money market or bond funds, but they come with greater risk, too.

Performance and risk. Look for a fund with a three- and five-year record, under the same manager, that beats its benchmark and its peers. But dig deeper. Year-by-year returns may reveal a nasty roller coaster ride. If you can, find out how the manager performed during market corrections. How did that U.S. stock fund you're eyeing fare over the last three months of 2018, when Standard & Poor's 500-stock index lost nearly 14%? A look at how a fund performed during good years and bad years can give you an idea of its volatility. Can you sit through the downdrafts without flinching?

Fees. You’ve heard it before: Fees eat away at your investment over time. A $10,000 investment growing 10% a year with a 1.5% management fee translates into roughly $50,000 after 20 years. But a similar investment in a fund with just 0.5% in expenses would be worth more than $60,000. Keep averages in mind as you scrutinize fund fees. The average U.S. stock mutual fund charges 1.07% in annual expenses; taxable bond mutual funds average 0.90%. Exchange-traded funds, available in HSA plans that have brokerage windows, charge even less. U.S. stock ETFs cost an average of 0.35% per year; taxable bond ETFs, 0.30%.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Nellie joined Kiplinger in August 2011 after a seven-year stint in Hong Kong. There, she worked for the Wall Street Journal Asia, where as lifestyle editor, she launched and edited Scene Asia, an online guide to food, wine, entertainment and the arts in Asia. Prior to that, she was an editor at Weekend Journal, the Friday lifestyle section of the Wall Street Journal Asia. Kiplinger isn't Nellie's first foray into personal finance: She has also worked at SmartMoney (rising from fact-checker to senior writer), and she was a senior editor at Money.

-

How to Invest as the AI Industry Grows Up

How to Invest as the AI Industry Grows UpHere’s where to find the winners as artificial intelligence transitions from an emerging technology to an adolescent one.

-

I’m 62 and worried about Social Security’s future. Should I take it early?

I’m 62 and worried about Social Security’s future. Should I take it early?A Social Security shortfall may be coming soon. We ask financial experts for guidance.

-

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online Bargains

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online BargainsFeature Amazon Resale products may have some imperfections, but that often leads to wildly discounted prices.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2025

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2025Roth IRAs Roth IRA contribution limits have gone up. Here's what you need to know.

-

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnb

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnbreal estate Here's what you should know before listing your home on Airbnb.

-

Five Ways to a Cheap Last-Minute Vacation

Five Ways to a Cheap Last-Minute VacationTravel It is possible to pull off a cheap last-minute vacation. Here are some tips to make it happen.

-

How Much Life Insurance Do You Need?

How Much Life Insurance Do You Need?insurance When assessing how much life insurance you need, take a systematic approach instead of relying on rules of thumb.

-

When Is Amazon Prime Day? Everything We Know, Plus the Best Deals on Apple, Samsung and More

When Is Amazon Prime Day? Everything We Know, Plus the Best Deals on Apple, Samsung and MoreAmazon Prime Amazon Prime Day is four days this year. Here are the key details you need to know, plus some of our favorite deals to shop during the sale.

-

How to Shop for Life Insurance in 3 Easy Steps

How to Shop for Life Insurance in 3 Easy Stepsinsurance Shopping for life insurance? You may be able to estimate how much you need online, but that's just the start of your search.

-

Five Ways to Shop for a Low Mortgage Rate

Five Ways to Shop for a Low Mortgage RateBecoming a Homeowner Mortgage rates are high this year, but you can still find an affordable loan with these tips.