Money Management Advice for Expat Retirees

You need to take extra steps to handle everything from banking to health care.

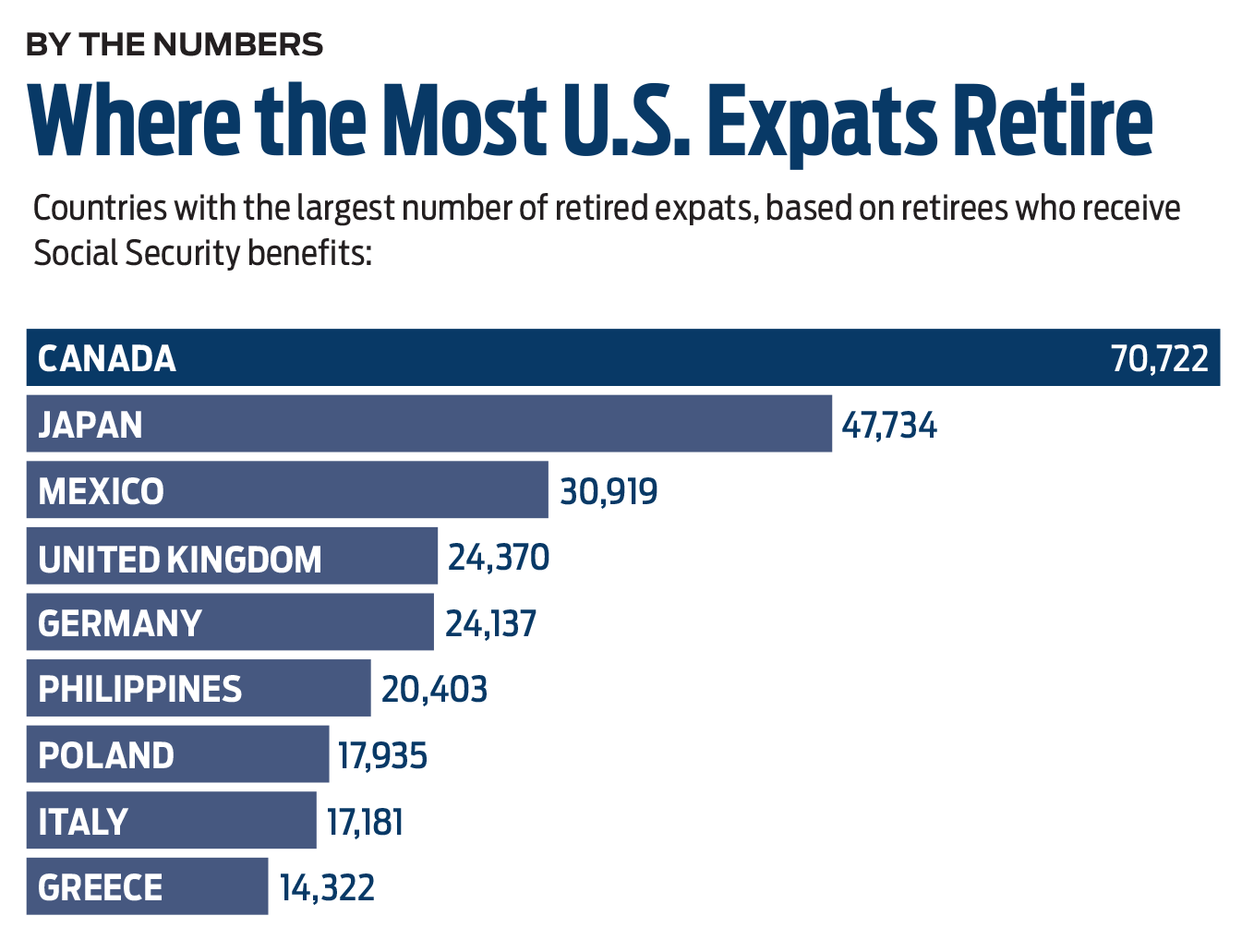

You’re finally ready to realize your dream of retiring outside the U.S. But before you give in to the lure of sunny beaches, a rich culture, family ties or the low cost of living in a new country, you’ll need to brush up on the nitty-gritty of managing your money as an expat.

Retiring abroad will likely make your financial life more complex, especially when it comes to taxes and your investment and bank accounts. But with some foresight—and help from a financial adviser and tax professional—you can overcome the challenges. “When you get overseas, you realize it’s not as difficult as you thought it was going to be,” says Jeff Opdyke, an American citizen currently living in Prague and editor of The Savvy Retiree, a publication from International Living magazine.

Banking and credit

You may be able to get by without opening a bank account in your country of residence, but there are good reasons to do so. It’s usually the most practical way to pay for rent, utilities and other local services. And if you use your U.S.-based debit card to make ATM withdrawals overseas, you’ll likely be hit with foreign-transaction fees and charges for using out-of-network machines. To choose a bank, ask locals which institutions they recommend, suggests Opdyke. He settled on a bank that offers an English-language mobile app.

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free E-Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Maintaining an account in the U.S. is usually a good idea, too. You can use it on visits stateside, and it may be the best way to pay taxes or deposit retirement-account distributions and Social Security benefits. (The Social Security Administration will deposit benefits to bank accounts held in most foreign countries, too.) Gabrielle Reilly, a certified financial planner who works with expats, says that many of her clients arrange large quarterly transfers of money from their U.S. bank account to their local one to keep fees to a minimum. (An outgoing international wire transfer often runs $30 to $50 or more.) Or, especially when dealing with currencies that tend to fluctuate widely against the U.S. dollar, such as the euro, it makes sense to initiate transfers when exchange rates are favorable, says Reilly.

To avoid hefty transfer fees from your U.S. bank account, consider a service such as TransferWise. TransferWise applies a market-based exchange rate to transfers (banks and other services often use less-favorable exchange rates) and charges you a percentage of the transaction. Sending $1,000 to a foreign account that holds Mexican pesos, for example, recently incurred a fee of about $11.

Steer clear of roadblocks. You may run into difficulties in both finding a bank account abroad and maintaining one in the U.S. The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), which went into effect in 2014, requires overseas banks to report to the IRS foreign assets held by U.S. taxpayers or face a stiff penalty. Some foreign banks refuse American customers because of the hassle, but “that’s been alleviated somewhat” as banks have become more familiar with the law, says Marylouise Serrato, executive director of advocacy organization American Citizens Abroad (ACA).

Under FATCA, U.S. citizens residing abroad must also report their holdings in foreign accounts (including investment accounts) on Form 8938 if total funds exceed $400,000 on the final day of the tax year for married people filing a joint tax return, or if balances are higher than $600,000 at any point during the year. For other taxpayers, the limits are $200,000 on the final day of the tax year or if funds exceed $300,000 at any time. In addition, you must file a Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR) with the U.S. Treasury Department if your total assets in foreign financial and investment accounts exceed $10,000 anytime during the calendar year.

One other potential obstacle: Some U.S. banks give the boot to expats who have no permanent U.S. address. And changing your mailing address to that of a relative or friend in the U.S. may not help you get around this problem. Financial institutions may review records from the U.S. Postal Service, check your computer or smartphone’s IP address when you log in to your account online, or track where your phone calls originate to figure out where you reside. And if, say, you use your sister’s address in California and the state receives a copy of Form 1099 reporting your interest income, you may be asked to explain to the state why you shouldn’t have to file a tax return there, says Jonathan Lachowitz, a CFP who works with expats.

One solution is to open a checking account that the State Department Federal Credit Union provides in partnership with American Citizens Abroad. Accustomed to serving employees of the U.S. Department of State, who work all over the world, the credit union offers the account to other Americans living abroad who have no domestic address. You must be a member of ACA to use the account (annual fee: $70, or $55 if you’re 65 or older).

Keeping your credit alive. Obtaining a credit card from an issuer based in another country is often difficult. Credit systems operate differently in other countries than in the U.S., and the credit history you’ve established in the U.S. isn’t usually useful to foreign issuers. You’re usually better off hanging on to your U.S. cards. They often offer superior rewards (such as cash back or airline miles earned with every purchase) than cards from foreign issuers, you can use them to make purchases on American websites (which may block cards from issuers outside the U.S.), and you’ll maintain a credit history in the U.S., says Lachowitz. A healthy credit profile comes in handy if you move back to the states.

If you want to use a U.S.-issued credit card in another country, make sure it doesn’t charge a foreign-transaction fee. Most travel rewards credit cards from major issuers don’t charge such fees, and some issuers—including Capital One and Discover—waive the fee on all their cards.

Investing

It’s usually best to keep your retirement and investment accounts with U.S. firms. If you open investment accounts abroad, you may have to contend with FATCA reporting rules. Plus, if you invest in non-U.S. mutual funds or exchange-traded funds through a foreign institution, they’re considered passive foreign investment companies (PFICs), and taxes are punitive.

One big caveat: Just as some U.S. banks reject American customers who move overseas, investment firms may tell expats with no permanent U.S. address that they’re no longer eligible to hold an IRA or a brokerage or other account. That’s what happened to Jean Nielsen, 77, who had IRAs and other investments with a brokerage firm in California when she relocated to Prague. She found Reilly Financial Advisors, the firm where CFP Gabrielle Reilly is employed, and with the firm’s help transferred her accounts to a new custodian. Her IRA’s required minimum distributions go into a U.S. financial institution’s cash account, and she can withdraw funds from it using a debit card attached to the account.

“I would say probably 90% of the people who reach out to me from outside the U.S.—mostly from Europe—do so because their financial firm has notified them that it won’t work with them,” says Reilly. Her employer has relationships with various U.S. custodians that allow her expat clients to hold investment accounts, and she transfers clients’ assets as quickly as possible. “If the institution liquidates an IRA and mails the account holder a check, that’s a fully taxable event on the entire amount. That can be devastating,” says Reilly. Well before you move, ask your investment company whether you can keep your accounts after you’ve left the country.

Another sticking point: Most U.S. financial institutions won’t allow citizens living overseas to buy mutual funds, although you may not be forced to sell holdings you already have when you move out of the U.S., says Lachowitz. And if you live in a European Union country, your U.S. and foreign brokers may prohibit you from purchasing U.S.-listed ETFs, too. So future transactions could be limited to individual stocks and bonds.

Taxes

You may be a bona fide resident of a foreign country, vowing never to return to the States. But if you’re a U.S. citizen and have income—whether it’s earned through a job or generated from a pension or retirement or investment accounts, and whether it originates inside or outside the U.S.—you’ll generally have to file a U.S. tax return and pay taxes on that income. (A couple of exceptions: You don’t have to file if your income falls below certain thresholds or if it is solely from Social Security benefits.)

“For those who reside abroad, it’s not obvious, and it’s usually a rude awakening when they find out they have to file,” says Katelynn Minott, a certified public accountant and partner for Bright!Tax, which provides tax services for expats. The tax-return deadline for those living abroad is June 15 rather than April 15. You’ll owe interest on any tax due that goes unpaid after the regular April deadline, but the late-payment penalty doesn’t kick in until after June 15.

Your former state may expect you to file a return and pay taxes, too, under the assumption that at the end of your time abroad, you will return to that state, so your residency was never relinquished.

“Some states are quite aggressive in their approach,” says Minott. In particular, California and New York are known for cracking down on residents who move overseas, she says. To avoid such challenges, some people relocate to a state with no income tax for a few months so they can establish residency, then move overseas.

Chances are you’ll have to file a return in your country of residence, too. And you may have to pay tax to the foreign jurisdiction on your U.S. earnings—possibly even on pension or other retirement income. Further muddling the picture, your new country’s tax year may span different dates than the U.S. tax year.

Given the complexity of taxation for expats, enlisting help is almost imperative. “You need a good accountant in the U.S. and one in your new country of residence,” says Reilly. Your U.S. accountant should be familiar with taxation for expats, and the tax pro you use in your new country should work regularly with U.S. citizens. The ACA offers a directory of tax services for expats.

Tax breaks for expats. On the bright side, some countries have tax treaties with the U.S. to alleviate the burden on expats. U.S. citizens who live in several countries—including Canada, Germany, Italy, the U.K. and Switzerland—don’t have to pay U.S. income tax on Social Security benefits. International treaties regarding gift and estate taxes may help you avoid double taxation on your financial gifts to others and on your assets after your death.

The U.S. also offers tax breaks to citizens living in other countries. The foreign tax credit allows you to reduce your U.S. tax obligation, in the form of a credit or itemized deduction, based on the foreign taxes you pay to your country of residence. The foreign earned income exclusion applies to foreign earnings that you get from a job or self-employment in your country of residence (but not to passive income, such as from a pension or investments). In 2020, you can exclude up to $107,600 of foreign earnings from your income for U.S. taxation.

Health care

Your U.S. tax liability may follow you to a new country, but Medicare doesn’t. If there’s any chance you may eventually live in the U.S. again, however, it’s wise to pay your Medicare Part B premiums. If you enroll in Medicare Part B later than the time you first become eligible, your monthly premium goes up by 10% for each 12 months that you delay. Plus, you can use Medicare coverage if you visit the U.S. to get health care.

The good news is that many countries offer high-quality health care at prices much lower than you’d pay in the U.S.—and for some retirees, that’s one of the main reasons they decide to move overseas. Usually, you have three ways to put together an affordable health care plan: Pay out of pocket, enlist in the country’s public health care program (if it’s available to foreign residents) or use private insurance, says Dan Prescher, a senior editor for International Living who splits his time between Mexico and the U.S.

If joining a country’s government-run health system is an option, premiums may be as low as $25 to $100 a month per person—or it may be free, according to Live Richer, Spend Less: International Living’s Ultimate Guide to Retiring Overseas, which Prescher coauthored with his wife, Suzan Haskins. You may face extended wait times to see physicians or to undergo nonemergency procedures, and public clinics and hospitals can be crowded.

For better service, explore private-sector choices in your country of residence. Some private insurers don’t offer new policies to those older than 65 or 70 (though they will continue an existing policy), and premiums may run higher than those for a country’s public system. But your medical costs could still be one-fifth to one-fourth of what you’d pay in the U.S., says Prescher. Because doctor visits and procedures are often relatively affordable without insurance in foreign countries, you may be able to pay out of pocket for basic care at private facilities and use either the public health program or a private policy for major surgeries. Even if you end up paying the full price for a major procedure, you’ll likely pay less than you would stateside. According to Patients Beyond Borders, which offers guidance for medical tourists, a hip replacement averages $17,200 in Costa Rica and $15,500 in Mexico, compared with $36,300 in the U.S. without insurance.

Another option: Some large insurers offer international health policies for expats. The Group Medical Insurance Plan from the Paris-based Association of Americans Resident Overseas is available to U.S. expats living in most countries. In 2020, the annual premium for a single person between age 60 and 69 who has a Silver level hospitalization and medical plan (covering 80% to 100% of expenses) is 4,017 euros, or about $4,360. You must also pay a $30 annual fee and be an AARO member, which runs 65 euros (about $70) yearly for an individual or 85 euros (about $90) for a couple.

The best places to retire abroad

International Living evaluated foreign countries’ attractiveness to retirees based on several criteria, including climate, health care and cost of living. For 2020, these are the top picks:

1. Portugal

2. Panama

3. Costa Rica

4. Mexico

5. Colombia

6. Ecuador

7. Malaysia

8. Spain

9. France

10. Vietnam

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Lisa has been the editor of Kiplinger Personal Finance since June 2023. Previously, she spent more than a decade reporting and writing for the magazine on a variety of topics, including credit, banking and retirement. She has shared her expertise as a guest on the Today Show, CNN, Fox, NPR, Cheddar and many other media outlets around the nation. Lisa graduated from Ball State University and received the school’s “Graduate of the Last Decade” award in 2014. A military spouse, she has moved around the U.S. and currently lives in the Philadelphia area with her husband and two sons.

-

How to Invest as the AI Industry Grows Up

How to Invest as the AI Industry Grows UpHere’s where to find the winners as artificial intelligence transitions from an emerging technology to an adolescent one.

-

I’m 62 and worried about Social Security’s future. Should I take it early?

I’m 62 and worried about Social Security’s future. Should I take it early?A Social Security shortfall may be coming soon. We ask financial experts for guidance.

-

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should Know

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should KnowHealthy Living on a Budget Medicare Part A and Part B leave gaps in your healthcare coverage. But Medicare Advantage has problems, too.

-

15 Reasons You'll Regret an RV in Retirement

15 Reasons You'll Regret an RV in RetirementMaking Your Money Last Here's why you might regret an RV in retirement. RV-savvy retirees talk about the downsides of spending retirement in a motorhome, travel trailer, fifth wheel, or other recreational vehicle.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2025

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2025Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits for state and local government workers in 2025. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Estate Planning Checklist: 13 Smart Moves

Estate Planning Checklist: 13 Smart Movesretirement Follow this estate planning checklist for you (and your heirs) to hold on to more of your hard-earned money.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.

-

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2025

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2025SEP IRA A good option for small business owners, SEP IRAs allow individual annual contributions of as much as $70,000 in 2025, up from $69,000 in 2024.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2025

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2025Roth IRAs Roth IRA contribution limits have gone up. Here's what you need to know.