Which Bucket Should Retirees Tap First, for Their Heirs' Sake?

Does it make more sense to pull money out of your Roth IRA or your brokerage account for your income? Consider the full picture when deciding whether to hold onto your taxable investments for the potential future step-up in basis.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

If you have a brokerage account, you’re probably familiar with the concept of cost basis (the original price you paid for an investment). But when you pass away, an investment’s cost basis changes — instead, it assumes the investment’s value at the date of your death. This is known as a “step-up” in basis, and it effectively makes gains during the original owner’s lifetime tax free for his or her heirs.*

For example, suppose you bought a stock for $20 per share, and now it’s worth $100. If you sell it, you will have a taxable capital gain of $80 per share. However, if it’s worth $100 at the date of your death, your heirs will only be taxed on any appreciation above $100 when they sell it. This applies exclusively to investments in taxable accounts, as opposed to tax-advantaged accounts like IRAs, Roth IRAs and 401(k) plans.

This tax rule can be a major benefit for families with wealth beyond what they will need for personal spending in retirement. The challenge for an investor (or financial adviser) is deciding whether to hold specific investments in anticipation of a step-up. If you also have assets in Roth or tax-deferred accounts, you will want to develop a strategy to determine which accounts to spend down and which to preserve.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Let’s take the case where you’re deciding whether to fund your retirement spending with qualified** tax-free Roth account distributions or by selling stock (or stock fund) investments in a taxable account. For now, we’ll assume your investments are similar in the two accounts (we’re aware that this is a big assumption). There are four major factors to consider:

| Factor | Situation that favors holding the taxable investment for the step-up |

|---|---|

| Investment cost basis (as percentage of value) | Low cost basis (i.e., a large potential gain) |

| Your tax rate on capital gains | High capital gain tax rate |

| Your life expectancy | Short life expectancy |

| Investment's dividend rate | Low dividend |

Hopefully, the first three factors listed don’t need much additional explanation: If you have a big, unrealized gain in your taxable investment, as well as a high tax rate, and you don’t expect to live long, holding onto that investment can benefit your heirs significantly. The dividend factor, however, isn’t as intuitive. Dividends matter because they are taxed every year. Compared to a stock with no dividend, a dividend-paying stock (with the same total return) incurs taxes sooner, and its value grows more slowly. The impact of this tax drag builds over the years, so it’s particularly meaningful for someone with a long life expectancy. Interestingly, if the stock pays no dividend, life expectancy doesn’t matter because there’s no annual tax drag.

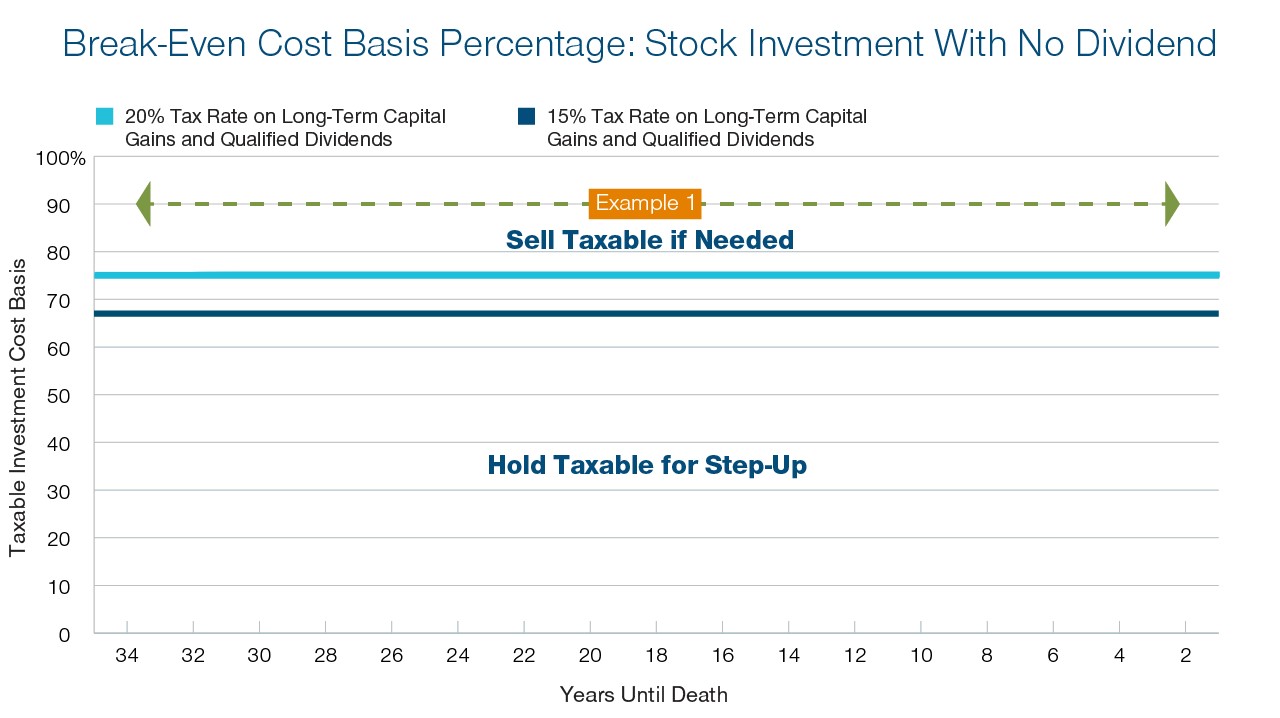

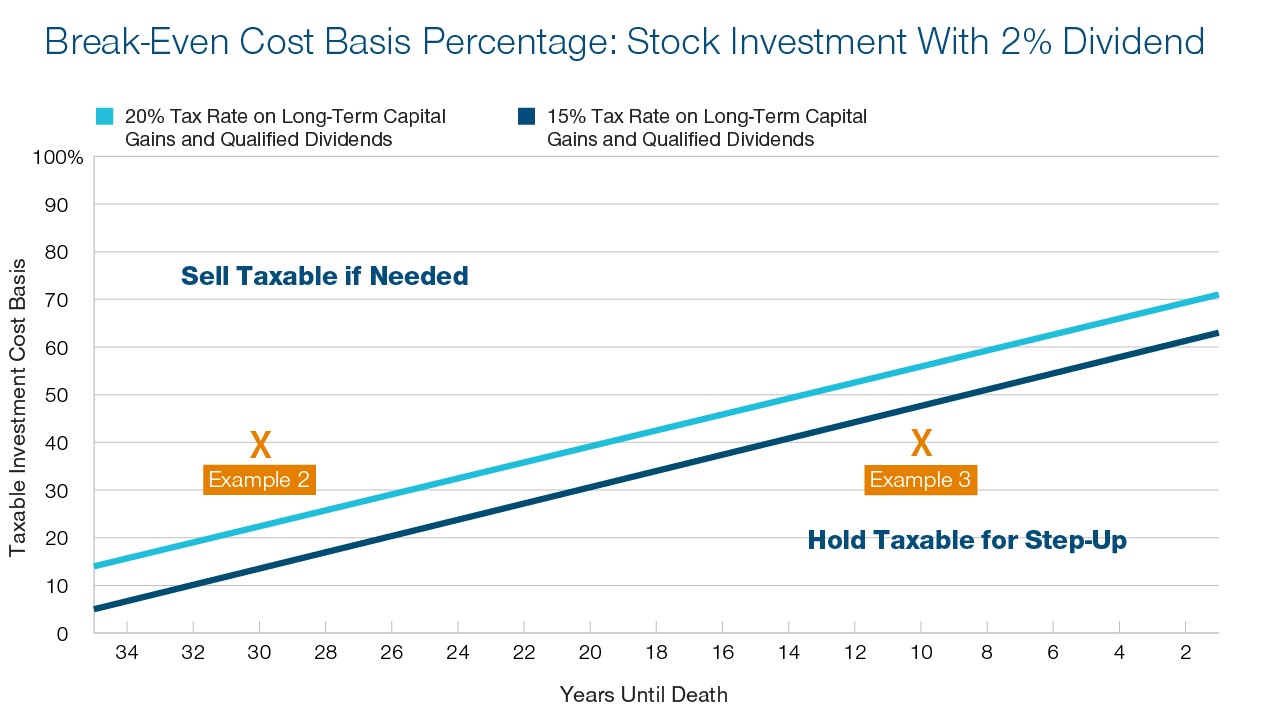

That’s a lot to consider, and these factors may not align the same way in your situation. Fortunately, we can use break-even cost basis percentage graphs to help with this decision.

Break-Even Cost Basis Percentage

Consider three examples in reference to the following charts. First, calculate your taxable investment cost basis percentage. To do that, divide the cost basis—usually available in your investment account — by the current value. Then, check it against the charts below. If your cost basis percentage is above the lines, it’s better to sell the taxable investment than to liquidate assets in a Roth account.

Source: Tax Efficient Withdrawal Strategies, T. Rowe Price. Assumptions: All investment returns come from appreciation (long-term) and qualified dividends, not ordinary income. Dividends are not reinvested. Cost basis is as a percentage of the investment value. After-tax value of a taxable asset to an heir is assumed to be 5% less than an equivalent Roth asset, due to ongoing tax benefit of the Roth account. Calculations based on formulas in: DiLellio, James, and Dan Ostrov. “Constructing Tax Efficient Withdrawal Strategies for Retirees.” (2018). Pepperdine University, Graziadio Working Paper Series. Paper 5.

EXAMPLE 1: Suppose you have a stock investment worth $10,000 with a $9,000 cost basis (90% of the value). And we’ll assume you will face capital gains taxes (at least 15%) on any gains you realize in your lifetime. Looking at the graph on the top, 90% is above the break-even lines for both the 15% and the 20% capital gains tax rates. That means if you need money for expenses, you should sell that taxable investment and hold onto any Roth accounts. That works out better long-term (after taxes) for your heirs.

EXAMPLE 2: Now suppose the same investment has a $4,000 cost basis (40%) and pays a 2% annual dividend. If you’re 55 and think you’ll live another 30 years, that 40% cost basis is above the lines on the second graph. So, you’d still want to sell the investment instead of taking a Roth distribution. Note that the break-even lines for a dividend rate below 2% would be higher on the graph — closer to the straight line in the “no dividend” graph.

EXAMPLE 3: But if you’re 85 and figure your life expectancy is under 10 years, that moves your 40% cost basis to the right and below the lines on the second graph. That means it makes sense to hold onto the investment for the step-up and use your Roth account to fund your expenses instead.

As you put this into practice, consider a few additional details when determining whether to sell appreciated assets over Roth account investments:

- A fair number of people don’t always face capital gains taxes, due to their income levels.*** This might be applicable in some years (e.g., before required minimum distributions) but not others. To the extent you can reap untaxed capital gains, don’t worry about preserving those assets for the step-up.

- Your investments probably aren’t exactly the same in your taxable and Roth accounts. If the appreciated investment has lower growth potential than your Roth holdings, you may be more inclined to sell the appreciated investment.

- The graphs above assume that your heirs will continue to benefit from tax-free- growth if they inherit your Roth account. If you think they’re more likely to cash it out quickly, then it’s relatively more attractive to leave them stepped-up taxable investments.****

Having assets you can leave your loved ones is a good problem to have. Proper planning can help ensure those assets are as tax efficient as possible.

* Exceptions may apply.

** Generally, Roth IRA distributions are qualified if the owner is over age 59 ½ and the account has been open at least five years.

***Long-term capital gains/qualified dividends rate: A 0% rate applies to taxpayers with taxable income not over $39,375 (single filers) and $78,750 (joint filers). A 15% rate applies to taxpayers with taxable income not over $434,550 (single filers) and $488,850 (joint filers). A 20% rate applies to taxpayers with taxable income above those levels.

**** This scenario could also occur if Congress passes legislation requiring inherited retirement accounts to be distributed more quickly than under current law.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Roger Young is Vice President and senior financial planner with T. Rowe Price Associates in Owings Mills, Md. Roger draws upon his previous experience as a financial adviser to share practical insights on retirement and personal finance topics of interest to individuals and advisers. He has master's degrees from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Maryland, as well as a BBA in accounting from Loyola College (Md.).

-

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live By

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live ByThe iconic football coach's philosophy can help retirees win at the game of life.

-

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USA

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USAThe donation by financier Ross Stevens is meant to be a "retirement program" for Team USA Olympic and Paralympic athletes.

-

10 Cheapest Places to Live in Colorado

10 Cheapest Places to Live in ColoradoProperty Tax Looking for a cozy cabin near the slopes? These Colorado counties combine reasonable house prices with the state's lowest property tax bills.

-

Don't Bury Your Kids in Taxes: How to Position Your Investments to Help Create More Wealth for Them

Don't Bury Your Kids in Taxes: How to Position Your Investments to Help Create More Wealth for ThemTo minimize your heirs' tax burden, focus on aligning your investment account types and assets with your estate plan, and pay attention to the impact of RMDs.

-

Are You 'Too Old' to Benefit From an Annuity?

Are You 'Too Old' to Benefit From an Annuity?Probably not, even if you're in your 70s or 80s, but it depends on your circumstances and the kind of annuity you're considering.

-

In Your 50s and Seeing Retirement in the Distance? What You Do Now Can Make a Significant Impact

In Your 50s and Seeing Retirement in the Distance? What You Do Now Can Make a Significant ImpactThis is the perfect time to assess whether your retirement planning is on track and determine what steps you need to take if it's not.

-

Your Retirement Isn't Set in Stone, But It Can Be a Work of Art

Your Retirement Isn't Set in Stone, But It Can Be a Work of ArtSetting and forgetting your retirement plan will make it hard to cope with life's challenges. Instead, consider redrawing and refining your plan as you go.

-

The Bear Market Protocol: 3 Strategies to Consider in a Down Market

The Bear Market Protocol: 3 Strategies to Consider in a Down MarketThe Bear Market Protocol: 3 Strategies for a Down Market From buying the dip to strategic Roth conversions, there are several ways to use a bear market to your advantage — once you get over the fear factor.

-

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works Instead

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works InsteadFor retirees with a pension, traditional withdrawal rules could be too restrictive. You need a tailored income plan that is much more flexible and realistic.

-

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look Like

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look LikeThis is when you should be shifting your focus from growing your portfolio to designing an income and tax strategy that aligns your resources with your purpose.

-

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your Stress

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your StressTo be confident about retirement, consider building a safety net by dividing assets into distinct layers and establishing a regular review process. Here's how.