Don’t Be Afraid to Invest in Emerging-Markets Stocks

Emerging-markets stocks have been beaten up so badly that they are a good value now.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

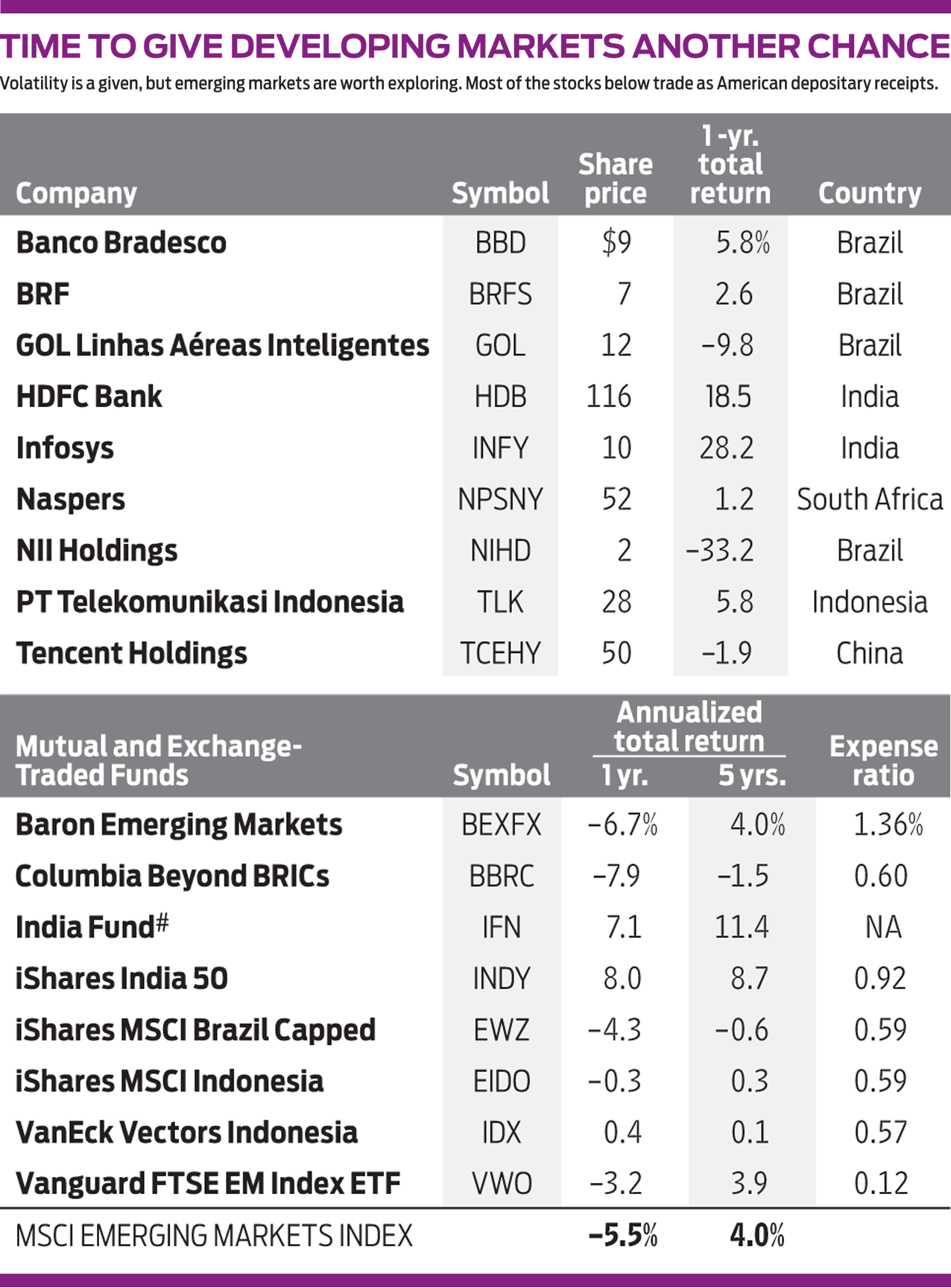

In my February 2017 column, I wrote that the stocks of emerging markets, which had been languishing for six years, “present a special opportunity.” It was a good call, but only temporarily. That year, the MSCI Emerging Markets index returned 37.3%, while Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index, the U.S. benchmark, returned 21.8%. In 2018, however, the stocks of emerging markets got clobbered, performing far worse than those in the U.S. or other developed nations. Over the past 10 years, MSCI Emerging Markets has returned just 8.0% annualized, compared with 15.2% for the S&P 500.

The disparity is shocking. You can’t just blame China, the largest emerging market by far. Although China’s gross domestic product growth rate has slid from double digits as recently as 2011 to an estimated 6.3% for 2019, its stock market has outperformed emerging markets as a whole. Other developing economies in Asia have been sluggish; markets in Latin America and the Middle East have disappointed.

But markets are about the future, not the past, and the future belongs to the aspiring, not to the mature. The forces of economic and demographic change are inexorable. In 1960, the U.S. represented 40% of global GDP; today, the proportion is 24% and falling. In 1960, Americans were 6% of the world’s population; today, they’re just 4.3%.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

I like China’s prospects, but that’s well explored in The Case for Investing in Chinese Stocks, so I’ll focus on the two-thirds of assets in the MSCI EM that are not invested in Chinese shares. Many emerging countries, such as Brazil, have suffered from poor governance; others, such as Thailand, are threatened by new U.S. trade policies. But investors can’t be frozen in the moment. Emerging markets have the long-term advantage of rising populations and, as education and technology improve, rising productivity.

Downshifting developed markets. Since the end of the Great Recession, GDP in Western Europe and Japan has been growing at an annual rate between 1% and 1.5%, on average. The U.S. has been growing at about 2.2% (a bit more last year because of the tax cut). While those growth rates appear to be the “new normal” for developed markets, emerging-markets economies have the potential to grow at rates of 4% or more. And emerging-markets stocks have been beaten up so badly in recent years that, unlike those in the U.S., they offer significant value.

A good example is Brazil, the fifth-largest country in the world by population, eighth by GDP. The exchange-traded fund iShares MSCI Brazil Capped (symbol EWZ, $40) has declined in five of the past eight years and has returned a measly 2.2% annualized for the past decade. Corruption and bad management have infested the government, and there’s no guarantee that Brazil’s unconventional new president, Jair Bolsonaro, can pull the country out of the doldrums. But gloom has been built into share prices. The price-earnings ratio of its Brazil index, based on year-ahead projected earnings, is 11, compared with 17 for the U.S.

The iShares ETF is a good way to invest, with an expense ratio of 0.59% and a dividend yield of 2.7%, but the fund is heavy on natural-resource firms that depend on commodity prices rather than on a pickup in Brazil’s own economy. Fortunately, unlike most other emerging markets, Brazil has an abundance of stocks listed on U.S. exchanges, trading as American depositary receipts. Banco Bradesco (BBD, $9), with a market cap of $67 billion, provides a way to benefit from a recovering economy. Shares have been volatile since Bolsonaro’s victory last fall, but they are still well priced. Shares of GOL Linhas Aéreas Inteligentes (GOL, $12), a small passenger and cargo airline based in São Paulo, have surged lately but are still down by about two-thirds since 2010. Also intriguing are small-cap stocks BRF (BRFS, $7), a pork and poultry producer that sells internationally, and NII Holdings (NIHD, $2), which, although headquartered in Reston, Va., provides wireless services under the Nextel brand in Brazil.

India beckons. India has one-seventh the GDP of the United States and more than four times the population. The Economist forecasts that India’s GDP will increase 7.4% this year, faster than any of the 41 other countries the magazine surveys. Unlike Brazil, India’s stock market has been relatively buoyant over the past decade but still flat in 2015, 2016 and 2018. Opportunities abound, and you can take advantage of them through the closed-end India Fund (IFN, $22), a particular bargain because it currently trades at a 9% discount to the net asset value of the shares it owns. Another good choice is iShares India 50 (INDY, $38), an ETF that owns the country’s largest companies, including some you can buy on U.S. exchanges. Two of those are Infosys (INFY, $10), the technology and outsourcing firm, yielding 3.2%, and HDFC Bank (HDB, $116), which has 5,000 branches across the country and a strong position in consumer and corporate finance.

Indonesia is the fourth-most-populous country in the world, with an economy growing at a 5.2% clip. The best stock for U.S. investors is probably PT Telekomunikasi Indonesia (TLK, $28), which provides mobile phone and Wi-Fi services and trades on the New York Stock Exchange as an ADR with a 3.5% yield. The best ETFs focused on the country are iShares MSCI Indonesia (EIDO, $27) and VanEck Vectors Indonesia (IDX, $24), which have portfolios stuffed with banking stocks—a good way to play any emerging economy.

There are dozens of emerging-markets ETFs, closed-end funds and mutual funds. Some focus on individual countries, from Egypt to Greece; others, such as Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets Index ETF (VWO, $44) and Baron Emerging Markets (BEXFX), a member of the Kiplinger 25, are more diversified but tend to be dominated by China. A few funds prefer companies in countries off the beaten path.

One is Columbia Beyond BRICs (BBRC, $17), an ETF that eschews the four large emerging markets—Brazil, Russia, India and China—in favor of smaller ones. Its 91-stock portfolio includes banks in Qatar, Romania and Malaysia; a telecom firm in Morocco; a drug manufacturer in Bangladesh; and an energy distributor in Thailand. The top holding is Naspers (NPSNY, $52), a 104-year-old South African media firm that owns 31% of Chinese internet giant Tencent Holdings (TCEHY, $50)—an investment worth about $145 billion, even though Naspers’s own market value is just $106 billion.

I have argued in the past that you can’t go too far wrong with an all-U.S. portfolio. True. But, once more, I believe that emerging markets present a special opportunity. The stocks are depressed, and the U.S. and other developed nations have not demonstrated that they will ever resume consistent economic growth rates above 3% or more than minuscule population gains. Emerging markets are volatile. But for the long term, you need their stocks and funds in your portfolio.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

QUIZ: Are You Ready To Retire At 55?

QUIZ: Are You Ready To Retire At 55?Quiz Are you in a good position to retire at 55? Find out with this quick quiz.

-

10 Decluttering Books That Can Help You Downsize Without Regret

10 Decluttering Books That Can Help You Downsize Without RegretFrom managing a lifetime of belongings to navigating family dynamics, these expert-backed books offer practical guidance for anyone preparing to downsize.

-

New Ways to Keep Online Accounts Safe

New Ways to Keep Online Accounts SafeAs cybercrime evolves, the strategies you use to protect yourself need to evolve, too.

-

5 Big Tech Stocks That Are Bargains Now

5 Big Tech Stocks That Are Bargains Nowtech stocks Few corners of Wall Street have been spared from this year's selloff, creating a buying opportunity in some of the most sought-after tech stocks.

-

How to Invest for a Recession

How to Invest for a Recessioninvesting During a recession, dividends are especially important because they give you a cushion even if the stock price falls.

-

10 Stocks to Buy When They're Down

10 Stocks to Buy When They're Downstocks When the market drops sharply, it creates an opportunity to buy quality stocks at a bargain.

-

How Many Stocks Should You Have in Your Portfolio?

How Many Stocks Should You Have in Your Portfolio?stocks It’s been a volatile year for equities. One of the best ways for investors to smooth the ride is with a diverse selection of stocks and stock funds. But diversification can have its own perils.

-

An Urgent Need for Cybersecurity Stocks

An Urgent Need for Cybersecurity Stocksstocks Many cybersecurity stocks are still unprofitable, but what they're selling is an absolute necessity going forward.

-

Why Bonds Belong in Your Portfolio

Why Bonds Belong in Your Portfoliobonds Intermediate rates will probably rise another two or three points in the next few years, making bond yields more attractive.

-

140 Companies That Have Pulled Out of Russia

140 Companies That Have Pulled Out of Russiastocks The list of private businesses announcing partial or full halts to operations in Russia is ballooning, increasing economic pressure on the country.

-

How to Win With Game Stocks

How to Win With Game Stocksstocks Game stocks are the backbone of the metaverse, the "next big thing" in consumer technology.