Pimco's Bill Gross Is Wrong About Stocks

Gross says that stocks "stink." But over the long-term, they'll prove to be the best investment.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Bill Gross, manager of the world’s largest mutual fund, touched off a heated reaction recently when he wrote that “the cult of equity is dying.” Most of the responses to his essay seemed to focus on his extremely negative view of the stock market. That was nothing new for Gross, whose enormously successful firm, Pimco, specializes in bonds. In a September 2002 newsletter piece titled “Dow 5,000,” Gross wrote, “My message is as follows: Stocks stink and will continue to do so, until they’re priced appropriately, probably somewhere around Dow 5,000, S&P 650, or Nasdaq God knows where.”

It was a terrible call. The Dow Jones industrial average never got close to 5,000 and is now over 13,000. Let’s stipulate that Gross knows—and loves—bonds better than stocks. That’s how he made his fortune. But let’s also not caricature the guy. He is making a serious point that revolves around the word cult. He believes that “cult followers”—that is, most investors—have embraced stocks to a degree that defies logic. Is he right? I’ll get to the answer a bit later. But first, understand that he’s clearly onto something with his contention that “the cult of equity is dying,” in the sense that investors are no longer as enamored of stocks as they were before the calamity of 2008.

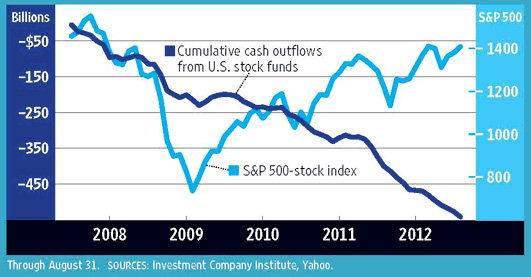

Investors Pulling Out

Total assets in stock mutual funds dropped from $6.4 trillion at the end of 2007 to $5.6 trillion as of June 2012, according to the Investment Company Institute, the fund industry’s trade group. Over the same period, assets in bond funds jumped from $1.7 trillion to $3.2 trillion. For the first six months of 2012, investors pulled $30 billion out of stock funds and added $125 billion to bond funds.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

The decline in stock investing is all the more remarkable because the Dow industrials have almost precisely doubled since the market hit bottom in March 2009. Investors are shoveling money into bond funds even though the S&P 500 is up 16% for the year and the yield on the ten-year Treasury bond is near a record low at 1.7%.

Investors have watched the train leave the station because they’re scared to death. A survey by the ICI found that the proportion of mutual fund investors who said they were either “unwilling to take any risk” or willing to take only “below-average risk for below-average gain” rose from 14% in 2008 to 23% in 2011. In 2000, 51% of Americans in their fifties had 80% or more of their 401(k) retirement assets invested in stocks; by 2010, the proportion with 80% or more in stocks had dropped to 26%.

The reasons are obvious. The first is the S&P 500’s 37% drop in 2008, the stock market’s worst calendar-year decline since 1931. Then you have the “flash crash” of 2010, when the Dow lost 600 points in a few minutes; the Bernie Madoff scandal; the Facebook IPO debacle; and the overall economic malaise. Many investors just want the stock market to go away.

But surveys and clever explanations aren’t necessary. All you need to know is that Pimco Total Return (symbol PTTDX), a medium-maturity bond port-folio that Gross manages, is by far the biggest mutual fund in the known universe, with $272.5 billion in assets. By contrast, the former champ, Vanguard 500 Index (VFINX), which tracks the S&P 500, holds $116 billion in assets.

If stocks ever had a cult following, it is no longer so. The thrust of Gross’s August newsletter is that it’s a good thing investors are cooling to stocks because stock returns are built on a fraud and an illusion. They have no right to have done as well as they have, he says, and they’re falling back to earth, where they belong.

Over the past 200 years, as Jeremy Siegel, the Wharton finance professor (and Kiplinger’s columnist), has shown, stocks have returned about 10% annualized. Gross, however, prefers to look at the stock market’s after-inflation return of 6.6% annualized. He argues that because gross domestic product “and wealth grew at 3.5% per year [in real terms], it seems only reasonable that the bondholder should have gotten a little bit less and the stockholder something more than that.” But, Gross says, not three percentage points more!

In his 2002 piece, Gross wrote, “Come on, stockholders of America, are you naïve, stupid, masochistic, or, better yet, in this for the ‘long run’?” Those last two words are a reference to the title of Siegel’s influential book, Stocks for the Long Run, which argued that stocks have not only earned much more than bonds over the years, they have done so with little more risk than bonds—thus making stocks superb investments.

There is no disputing the excellent performance of stocks. But Gross is suggesting that investors have participated in a Ponzi scheme, that returns have been higher than economic growth has justified and are unlikely to continue in the future. His main argument is that if an economy grows at 3.5% a year, as ours has for the past century or so (not including inflation), then stock returns, which in theory reflect the value of businesses, should also grow by roughly that rate. Instead, he notes, returns have exceeded economic growth by 3.1 percentage points per year.

But Gross’s critics, including Siegel himself, say that the bond wizard’s analysis is wrong and that long-term after-inflation returns in the area of 6.6% per year are reasonable.

Extra Compensation

I agree with them. Here’s why: Stock returns reflect two elements, economic growth plus dividend payments, just as the return on a rental property would reflect the rising value of the house plus rental payments. (In the case of a stock, companies sometimes forgo paying dividends to shareholders and reinvest profits to promote future growth.) Not only that, but, as Gross himself notes, stock investors are also supposed to get paid for taking a risk. This extra payment is called the equity risk premium, and the irony is that in times such as these, when fear runs high, the risk premium rises—and investors get higher, not lower, returns to compensate them.

One way to determine the level of fear in the market is to compare the returns of stocks to the returns of a presumably risk-free asset, such as a Treasury bond. This comparison is often called the Fed model because the Federal Reserve hinted 15 years ago that it followed the formula. The price-earnings ratio today for the S&P 500 is 13, based on forecasts of profits for the year ahead. If we invert the P/E, we get something known as the earnings yield. This figure is, essentially, the yield investors would receive if all the profits earned by S&P 500 companies were distributed to shareholders as dividends.

So if the P/E is currently 13, then the E/P, or earnings yield, is 7.4%. Compare that with a current return of just 1.7% for the ten-year Treasury, and it means that investors are getting paid an extra six percentage points to take on the risk of owning a stock rather than government debt. That sounds like a good deal to me.

I see a lot of firms with a good shot at increasing their earnings faster than the economy’s 3.5% growth rate or the stock market’s 6.6% annualized return after inflation that appear to be bargains in a time of fear. And many pay good dividends, too.

The Dow Jones industrial average is the mother lode of superb companies. Here are five favorite components (prices are as of September 7): International Business Machines (IBM), which, at $200, trades at 12 times estimated year-ahead earnings and is expected to increase its free cash flow by one-third over the next two years (see Opening Shot); Cisco Systems (CSCO), the giant maker of networking equipment, which sells for 9 times projected earnings and recently raised its quarterly dividend from 6 cents to 14 cents a share (the stock, at $20, yields 2.9%); drug maker Merck (MRK), which, at $44, has a P/E of 12 and a yield of 3.8%, more than twice that of the ten-year T-bond; Microsoft (MSFT), which, at $31, sells for 9 times year-ahead profit estimates and yields 2.6%; and insurer Travelers (TRV), which, at $65, trades at 9 times earnings and yields 2.8%. Or just buy SPDR Dow Jones Industrial Average ETF (DIA), an exchange-traded fund that tracks the Dow.

There’s a lot of fear out there, and it’s a good bet that all that worrying is depressing stock prices. In the short term, that fear may actually be justified. But, in the longer term, stock prices move jerkily but inexorably higher. And that’s history, not a cult, speaking.

James K. Glassman is executive director of the Bush Institute, which just published a new book on the U.S. economy, The 4% Solution. He owns none of the stocks mentioned.

Kiplinger's Investing for Income will help you maximize your cash yield under any economic conditions. Subscribe now!

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K 'Senior Deduction' Means for Medicare IRMAA Costs

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K 'Senior Deduction' Means for Medicare IRMAA CostsTax Breaks A new deduction for people over age 65 has some thinking about Medicare premiums and MAGI strategy.

-

U.S. Congress to End Emergency Tax Bill Over $6,000 Senior Deduction and Tip, Overtime Tax Breaks in D.C.

U.S. Congress to End Emergency Tax Bill Over $6,000 Senior Deduction and Tip, Overtime Tax Breaks in D.C.Tax Law Here's how taxpayers can amend their already-filed income tax returns amid a potentially looming legal battle on Capitol Hill.

-

5 Investing Rules You Can Steal From Millennials

5 Investing Rules You Can Steal From MillennialsMillennials are reshaping the investing landscape. See how the tech-savvy generation is approaching capital markets – and the strategies you can take from them.

-

5 Big Tech Stocks That Are Bargains Now

5 Big Tech Stocks That Are Bargains Nowtech stocks Few corners of Wall Street have been spared from this year's selloff, creating a buying opportunity in some of the most sought-after tech stocks.

-

How to Invest for a Recession

How to Invest for a Recessioninvesting During a recession, dividends are especially important because they give you a cushion even if the stock price falls.

-

10 Stocks to Buy When They're Down

10 Stocks to Buy When They're Downstocks When the market drops sharply, it creates an opportunity to buy quality stocks at a bargain.

-

How Many Stocks Should You Have in Your Portfolio?

How Many Stocks Should You Have in Your Portfolio?stocks It’s been a volatile year for equities. One of the best ways for investors to smooth the ride is with a diverse selection of stocks and stock funds. But diversification can have its own perils.

-

An Urgent Need for Cybersecurity Stocks

An Urgent Need for Cybersecurity Stocksstocks Many cybersecurity stocks are still unprofitable, but what they're selling is an absolute necessity going forward.

-

Why Bonds Belong in Your Portfolio

Why Bonds Belong in Your Portfoliobonds Intermediate rates will probably rise another two or three points in the next few years, making bond yields more attractive.

-

140 Companies That Have Pulled Out of Russia

140 Companies That Have Pulled Out of Russiastocks The list of private businesses announcing partial or full halts to operations in Russia is ballooning, increasing economic pressure on the country.

-

How to Win With Game Stocks

How to Win With Game Stocksstocks Game stocks are the backbone of the metaverse, the "next big thing" in consumer technology.