Dollar-Cost Averaging Into Stocks: How Does DCA Investing Work?

A brief primer on dollar-cost averaging into stocks, the popular set-it-and-forget-it investing method.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Dollar-cost averaging (DCA) is one of the most important concepts an individual investor can master.

Fortunately, it's also one of the easiest.

The idea of dollar-cost averaging is to invest your dollars in a stock, exchange-traded fund (ETF) or other security in regular, equal portions over time.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

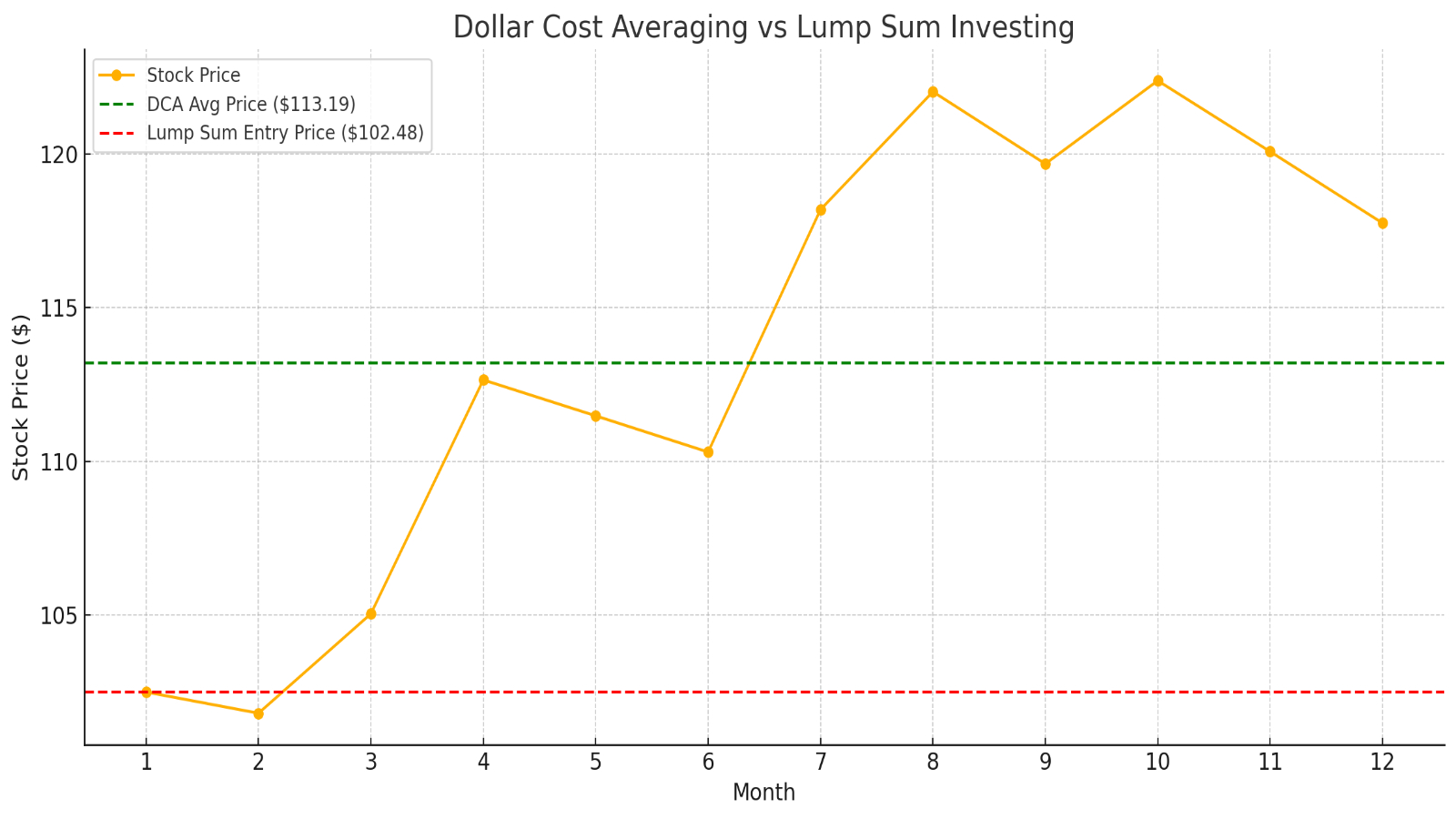

Sure, you could invest your cash in a single lump sum, but how do you know you're getting the best price? (Remember: The idea is to buy low.)

In the short term, many stock movements can be random, and even the pros are more likely to fail than succeed when trying to precisely time the market.

Dollar-cost averaging doesn't guarantee you the lowest cost basis on your investments. It can, however, produce a lower average cost basis over a longer period of time than lump-sum investing.

And, again, it's easy to do.

How dollar-cost averaging works

If you have a 401(k) or similar plan where you automatically invest a percentage of every paycheck in a retirement plan, guess what? You are already dollar-cost averaging.

That's because every pay period, you're investing the same amount of cash like clockwork.

But say you want to do this in an IRA or brokerage account. Here's an example of how this would work with an individual stock.

You have $10,000 to invest in, say, grocery chain Kroger (KR). You effectively have two options:

1.) Make a lump-sum investment of $10,000. If shares in the supermarket chain decline soon after you make your investment, however, you might kick yourself over your poor timing.

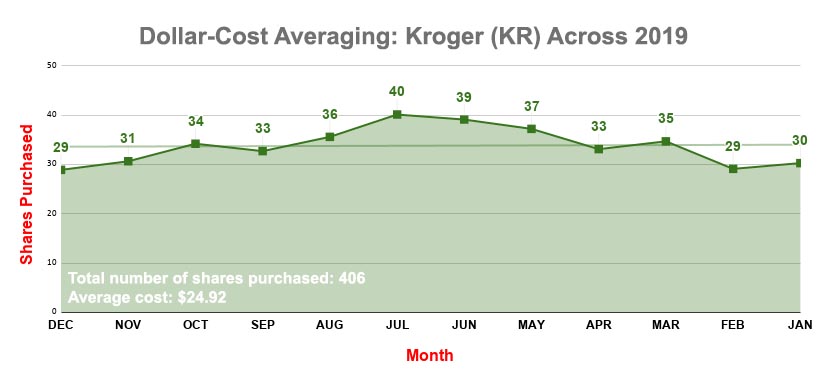

2.) Dollar-cost average, investing the $10,000 gradually and at regular intervals. For instance, you might purchase $833.33 worth of KR stock every month for 12 months.

The beauty of dollar-cost averaging is that if Kroger stock does indeed decline over that period of time, you'll buy KR shares at a lower cost. Thus, you'll get more shares for your $833.33, too.

Here's how dollar-cost averaging with KR would've looked across 2019, assuming you had bought at the closing price of each month:

In short, DCA lets an investor automatically buy more shares in a company when they're cheaper, and fewer shares when they're more expensive.

Nothing's a guarantee, of course

As with everything in investing, DCA is not without its detractors. Dollar-cost averaging can underperform lump-sum investing at times.

But while systematic investing does not guarantee a profit or protect against loss, it can lift a psychological brick or two off your shoulders.

With DCA, you don't need to agonize over whether you should buy right now, or wait for earnings, or wait for a market dip. You just implement the system and keep yourself updated on the stock over time.

Investors also need to consider whether they have the stomach to keep buying when share prices are falling or the stock market is selling off.

Dollar-cost averaging doesn't mean to throw good money after bad if the company's narrative has changed considerably. But it does mean being consistent through short-term ups and downs.

That said, DCA can be a good strategy for long-term investors who just want to set it and forget it.

Related Content

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Dan Burrows is Kiplinger's senior investing writer, having joined the publication full time in 2016.

A long-time financial journalist, Dan is a veteran of MarketWatch, CBS MoneyWatch, SmartMoney, InvestorPlace, DailyFinance and other tier 1 national publications. He has written for The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg and Consumer Reports and his stories have appeared in the New York Daily News, the San Jose Mercury News and Investor's Business Daily, among many other outlets. As a senior writer at AOL's DailyFinance, Dan reported market news from the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

Once upon a time – before his days as a financial reporter and assistant financial editor at legendary fashion trade paper Women's Wear Daily – Dan worked for Spy magazine, scribbled away at Time Inc. and contributed to Maxim magazine back when lad mags were a thing. He's also written for Esquire magazine's Dubious Achievements Awards.

In his current role at Kiplinger, Dan writes about markets and macroeconomics.

Dan holds a bachelor's degree from Oberlin College and a master's degree from Columbia University.

Disclosure: Dan does not trade individual stocks or securities. He is eternally long the U.S equity market, primarily through tax-advantaged accounts.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

AI Sparks Existential Crisis for Software Stocks

AI Sparks Existential Crisis for Software StocksThe Kiplinger Letter Fears that SaaS subscription software could be rendered obsolete by artificial intelligence make investors jittery.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

Why Invest In Mutual Funds When ETFs Exist?

Why Invest In Mutual Funds When ETFs Exist?Exchange-traded funds are cheaper, more tax-efficient and more flexible. But don't put mutual funds out to pasture quite yet.

-

Social Security Break-Even Math Is Helpful, But Don't Let It Dictate When You'll File

Social Security Break-Even Math Is Helpful, But Don't Let It Dictate When You'll FileYour Social Security break-even age tells you how long you'd need to live for delaying to pay off, but shouldn't be the sole basis for deciding when to claim.

-

I'm an Opportunity Zone Pro: This Is How to Deliver Roth-Like Tax-Free Growth (Without Contribution Limits)

I'm an Opportunity Zone Pro: This Is How to Deliver Roth-Like Tax-Free Growth (Without Contribution Limits)Investors who combine Roth IRAs, the gold standard of tax-free savings, with qualified opportunity funds could enjoy decades of tax-free growth.

-

One of the Most Powerful Wealth-Building Moves a Woman Can Make: A Midcareer Pivot

One of the Most Powerful Wealth-Building Moves a Woman Can Make: A Midcareer PivotIf it feels like you can't sustain what you're doing for the next 20 years, it's time for an honest look at what's draining you and what energizes you.

-

Stocks Make More Big Up and Down Moves: Stock Market Today

Stocks Make More Big Up and Down Moves: Stock Market TodayThe impact of revolutionary technology has replaced world-changing trade policy as the major variable for markets, with mixed results for sectors and stocks.

-

I'm a Wealth Adviser Obsessed With Mahjong: Here Are 8 Ways It Can Teach Us How to Manage Our Money

I'm a Wealth Adviser Obsessed With Mahjong: Here Are 8 Ways It Can Teach Us How to Manage Our MoneyThis increasingly popular Chinese game can teach us not only how to help manage our money but also how important it is to connect with other people.

-

Looking for a Financial Book That Won't Put Your Young Adult to Sleep? This One Makes 'Cents'

Looking for a Financial Book That Won't Put Your Young Adult to Sleep? This One Makes 'Cents'"Wealth Your Way" by Cosmo DeStefano offers a highly accessible guide for young adults and their parents on building wealth through simple, consistent habits.