Indexing in Question

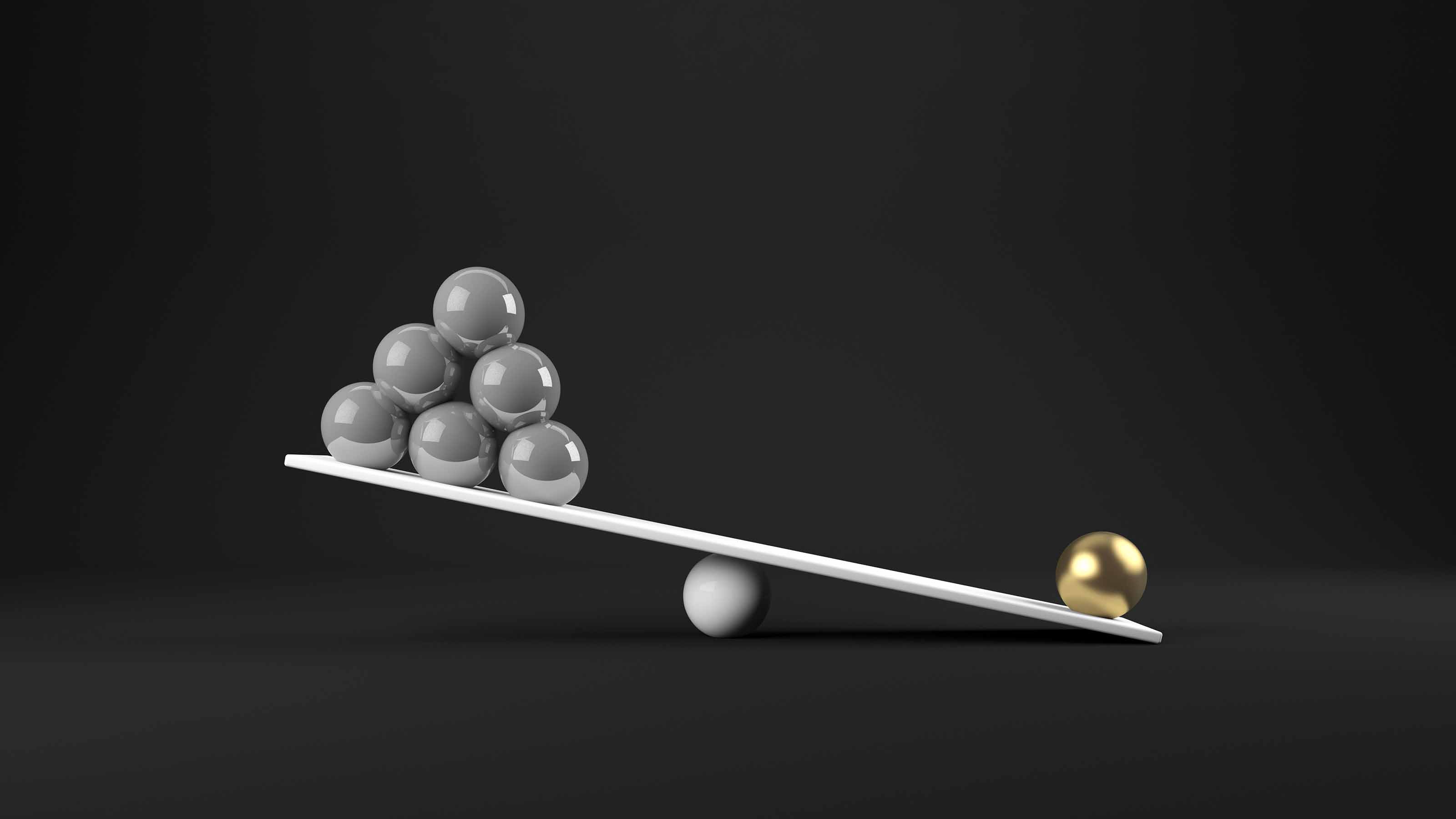

Actively managed funds are trouncing S&P 500 index funds this decade.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

We all know the case for indexing. Roughly two-thirds of all actively managed stocks funds fail to match the performance of their indexes. The overwhelming majority of these funds' richly compensated managers don't do as well as a blindfolded chimpanzee throwing darts at the stock tables.

But suppose it's not that simple. Suppose Jack Bogle was wrong. In 1976, Bogle created the first index fund for individual investors, Vanguard Index 500 (symbol VFINX). Bogle built Vanguard into an empire-based on the principles of low costs and indexing.

Proudly calling themselves Bogleheads, his disciples launched an online forum, diehards.org, and have dozens of local chapters around the country. Their mantra: Low-cost index funds that are designed to track the market do better than actively managed funds.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

So far this decade, the record doesn't bear out Bogle and his supporters, at least as far as index funds tied to Standard & Poor's 500-stock index are concerned. And those are the important ones because they represent the great majority of assets in indexed mutual funds.

Since New Year's Day 2000, the S&P 500 has returned a grand total of 3.3% through March 31. That's 0.4% annualized. (Not counting dividends, the index actually declined 10%.)

Some observers have used the pitiful performance of the S&P to buttress their argument that this has been a "lost decade" for stocks. Well, it has been a lost decade for some stocks.

The S&P consists of about 500 mostly large companies, weighted by their market value (share price multiplied by number of shares outstanding.) Thus, ExxonMobil, the nation's biggest company by market value, represents nearly 4% of the index, while smaller companies, such as Teradyne, count for just 0.01%.

At the start of the decade, technology stocks accounted for 35% of the S&P. Today, tech's weighting is only half that. The S&P lost 47% during the 2000-02 bear market. The tech-laden Nasdaq Composite still trades at less than half its early 2000 peak of more than 5,000.

How hard was it to do better than the S&P? The Leuthold Group, a Minneapolis-based investment research firm, calculates that 86% of its 150 domestic industry groups have beaten the S&P so far this decade. The median industry group gained 98%, not including dividends. "A purely random 'shotgun' approach to group rotation won big against the S&P 500 this decade," Leuthold says.

Most of the industries that trail the S&P are those you'd expect: They're connected to technology and telecommunications, which soared during the tech bubble. A few are casualties of the more recent selloff in financials.

Investing overseas has been far more lucrative than owning the S&P 500. Compared with stock markets in 49 developed and emerging countries, the S&P index finished dead last. The biggest gainers were emerging markets. Colombia gained 1300%, Russia gained 776% and India rose 326%.

Fans of indexing could counter that the S&P isn't as good an index as the Dow Jones Wilshire 5000 or the Russell 3000. The S&P mirrors more than 70% of the market's total value, but the Wilshire and the Russell are designed to reflect the entire market. Since the start of the decade, though, the Wilshire, including dividends, has returned a total of just 10% -- still well behind the overwhelming majority of domestic industry groups and almost every foreign bourse.

The key to success in this decade has resided elsewhere. First, you had to invest overseas. The MSCI EAFE index, which tracks developed foreign markets, returned 41% (4.3% annualized) from the start of the decade through March 31.

Next you had to diversify into stocks of small companies. The S&P SmallCap 600 index has returned 98%, or 8.6% annualized. Finally, you had to favor bargain-priced value stocks. The Russell 1000 Value index, which tracks the cheaper half of the 1,000 largest U.S. companies, returned 54%, or 5.4% annualized.

You would have helped your returns by banking on the future and investing in emerging markets. The Vanguard Emerging Markets Stock Index (VEIEX) returned 175% since the start of the decade, or an annualized 13.1%.

Even better, you could have invested in real estate investment trusts. The S&P REIT index has returned 247% (16.3% annualized) so far in the '00s.

The bottom line: There's nothing wrong with indexing. But no matter how you invest, you can't afford to check your brain at the front door.

When valuations on tech stocks reached the stratosphere in 2000 and caused tech's weighting in the S&P 500 to rocket to 35%, the sensible strategy would have been to pare back on S&P 500 index funds, as well, of course, as other funds with big tech allocations.

Similarly, to succeed in stocks this decade, you had to see the values overseas -- particularly in emerging markets.

Ironically, I think the S&P 500, which is dominated by stocks of large companies, will be a good place to be the rest of this decade. Those large companies generally have stronger balance sheets and are less richly valued than smaller companies are today.

Plus, large companies tend to derive a larger portion of their revenues overseas than small companies do. With the U.S. economy growing slowly at best and most likely in recession, the ability to generate significant sales overseas could be the key factor favoring large-cap stocks.

But I don't think you should abandon funds that invest in foreign stocks, particularly in emerging markets.

Personally, I think I can pick funds that will beat the market indexes over time. But it's hard as the dickens, and I know I will often fail. Most people lack the time and inclination to select winners among actively managed funds. Successful indexing, however, requires more than simply buying the S&P 500.

Steven T. Goldberg (bio) is an investment adviser and freelance writer.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K 'Senior Deduction' Means for Medicare IRMAA Costs

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K 'Senior Deduction' Means for Medicare IRMAA CostsTax Breaks A new deduction for people over age 65 has some thinking about Medicare premiums and MAGI strategy.

-

U.S. Congress to End Emergency Tax Bill Over $6,000 Senior Deduction and Tip, Overtime Tax Breaks in D.C.

U.S. Congress to End Emergency Tax Bill Over $6,000 Senior Deduction and Tip, Overtime Tax Breaks in D.C.Tax Law Here's how taxpayers can amend their already-filed income tax returns amid a potentially looming legal battle on Capitol Hill.

-

5 Investing Rules You Can Steal From Millennials

5 Investing Rules You Can Steal From MillennialsMillennials are reshaping the investing landscape. See how the tech-savvy generation is approaching capital markets – and the strategies you can take from them.

-

ESG Gives Russia the Cold Shoulder, Too

ESG Gives Russia the Cold Shoulder, TooESG MSCI jumped on the Russia dogpile this week, reducing the country's ESG government rating to the lowest possible level.

-

The 10 Best Schwab Funds for 2022

The 10 Best Schwab Funds for 2022ETFs Whether you're looking to build a core portfolio or position yourself for 2022, Schwab funds offer diversified exposure for a song.

-

New PINK Healthcare ETF Will Donate Fees to Cancer Research

New PINK Healthcare ETF Will Donate Fees to Cancer ResearchIndex Funds Simplify has launched a rare actively managed fund in the healthcare sector. It’s not cheap, but you’ll feel good about where your fees are going.

-

A Simple Portfolio Is All You Need

A Simple Portfolio Is All You NeedFinancial Planning It’s possible to build wealth with only a few funds—or even just one.

-

PODCAST: ETFs and Mutual Funds with Todd Rosenbluth

PODCAST: ETFs and Mutual Funds with Todd RosenbluthIndex Funds Which is better: ETFs or mutual funds? And how do you decide where to put your investments? CFRA fund expert Todd Rosenbluth has some answers. Also, how to take advantage of your leased car’s true value.

-

Water Investing: 5 Funds You Should Tap

Water Investing: 5 Funds You Should TapETFs As the importance of water sustainability becomes ever more apparent, so too do the potential rewards of investing in water.

-

The Truth About Index Funds

The Truth About Index FundsIndex Funds You may think you're diversified by buying an S&P 500 Index fund, but you're making a substantial wager on a handful of stocks.

-

10 Best Value ETFs to Buy for Bundled Bargains

10 Best Value ETFs to Buy for Bundled BargainsETFs Value stocks are finally having their day, and many expect the run to continue. These are the best value ETFs to leverage this long-awaited revival.