R.I.P. 60-40 Portfolio

The old standby allocation of 60% stocks and 40% government bonds might not work for buy-and-hold investors anymore.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Jared Woodard is head of the Research Investment Committee at BofA Securities.

What is the 60-40 portfolio, and why has it been the go-to model for many investors? In a 60-40 portfolio, 60% of assets are invested in stocks and 40% in bonds—often government bonds. The reason it has been popular over the years is that traditionally, in a bear market, the government bond portion of a portfolio has functioned as insurance by providing income to cushion stock losses. In addition, bonds tend to rise in price as stock prices fall.

Why do you say that the 60-40 portfolio is dead? The problem is that as yields on bonds head lower and lower—the 10-year Treasury note pays 0.7% per year—there’s less return in fixed-income securities for buy-and-hold investors. So that insurance works less well over time. Plus, the prospect of government policies to boost economic growth increases the risk of inflation. Treasuries could become more risky as interest rates start to rise and prices, which move in the opposite direction, fall.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

But don’t bonds limit volatility in your portfolio? Bonds can become very volatile. Look back at 2013, after the Federal Reserve said it would reduce purchases of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. There was a period of incredible volatility for bonds—known as the taper tantrum—as investors adjusted. Our argument is that as the prospects increase for more government intervention in the markets to support economic growth, the risk goes up that Treasuries will become a source of volatility.

What’s a better portfolio allocation now? There are two parts to that question. First, who is the investor? Older investors with specific income needs may find that their overall allocation to fixed income might not need to change much—but the kind of fixed income investments they own might need to be very different. Younger investors might find that they can tolerate the volatility of the stock market over the course of an entire investing career, given the difference in return from stocks over bonds.

And the second part? That’s the economic outlook. If we were at the end of an expansion, it would make sense to be more cautious. But we’re coming out of a recession, and prospects for corporate earnings and economic growth are much higher next year. At the start of a business cycle and new bull market, being too cautious means you miss out on the full returns of that cycle.

What fixed-income holdings do you prefer now, and why? Think in terms of sources of risk. Treasury bonds won’t default, but inflation and higher interest rates are big risks. Other bonds yield more, but they have credit risk, or the risk of not being paid back in full. Our contention is that the fixed-income portion of your portfolio should feature more credit and stock market risk and less interest rate risk.

We think the credit risk is worth taking in corporate bonds rated triple B, or even in higher-rated slices of the high-yield market. We also like preferred stocks and convertible bonds, which have characteristics of both stocks and bonds. These four categories can yield 2.5% to 4.5% today. Real estate investment trusts that invest in mortgages yield about 8% and pose less risk than REITs investing in commercial real estate. Finally, some 80% or more of S&P 500 companies pay dividends that are higher than the yield of 10-year Treasuries.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Anne Kates Smith brings Wall Street to Main Street, with decades of experience covering investments and personal finance for real people trying to navigate fast-changing markets, preserve financial security or plan for the future. She oversees the magazine's investing coverage, authors Kiplinger’s biannual stock-market outlooks and writes the "Your Mind and Your Money" column, a take on behavioral finance and how investors can get out of their own way. Smith began her journalism career as a writer and columnist for USA Today. Prior to joining Kiplinger, she was a senior editor at U.S. News & World Report and a contributing columnist for TheStreet. Smith is a graduate of St. John's College in Annapolis, Md., the third-oldest college in America.

-

Farmers Brace for Another Rough Year

Farmers Brace for Another Rough YearThe Kiplinger Letter The agriculture sector has been plagued by low commodity prices and is facing an uncertain trade outlook.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayPresident Trump said he will decide within the next 10 days whether or not the U.S. will launch military strikes against Iran.

-

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K Senior Tax Deduction Means for Medicare IRMAA

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K Senior Tax Deduction Means for Medicare IRMAATax Breaks A new tax deduction for people over age 65 has some thinking about Medicare premiums and MAGI strategy.

-

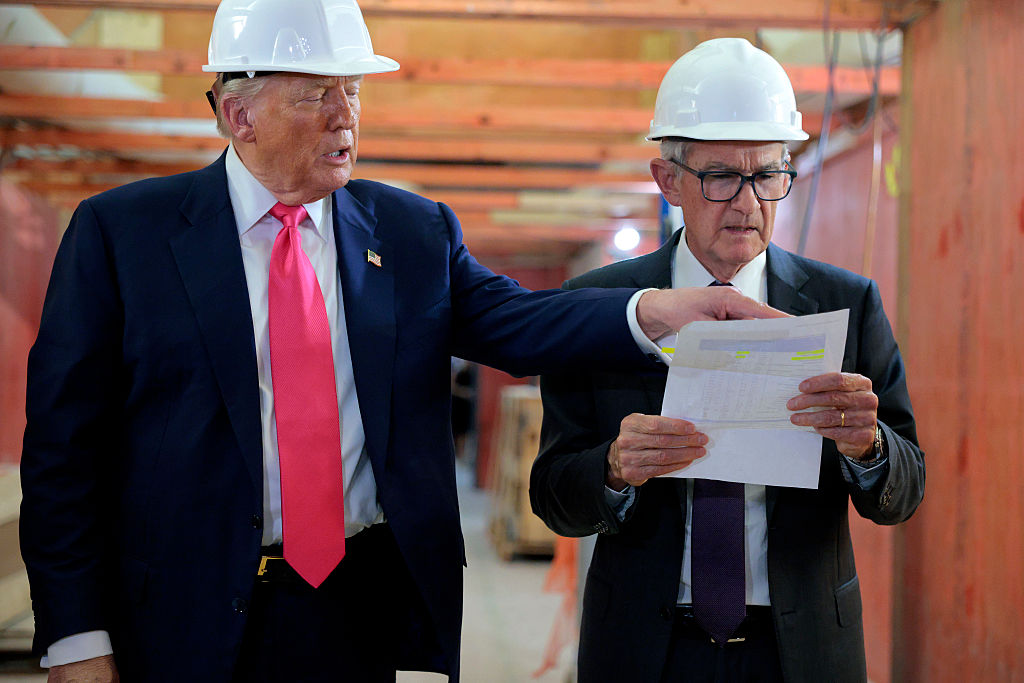

Big Change Coming to the Federal Reserve

Big Change Coming to the Federal ReserveThe Lette A new chairman of the Federal Reserve has been named. What will this mean for the economy?

-

Job Growth Sizzled to Start the Year. Here's Why It's Unlikely to Impact Interest Rates

Job Growth Sizzled to Start the Year. Here's Why It's Unlikely to Impact Interest RatesThe January jobs report came in much stronger than expected and the unemployment rate ticked lower to start 2026, easing worries about a slowing labor market.

-

Why the Next Fed Chair Decision May Be the Most Consequential in Decades

Why the Next Fed Chair Decision May Be the Most Consequential in DecadesKevin Warsh, Trump's Federal Reserve chair nominee, faces a delicate balancing act, both political and economic.

-

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to Know

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to KnowPresident Donald Trump announced Kevin Warsh as his selection for the next chair of the Federal Reserve, who will replace Jerome Powell.

-

January Fed Meeting: Updates and Commentary

January Fed Meeting: Updates and CommentaryThe January Fed meeting marked the first central bank gathering of 2026, with Fed Chair Powell & Co. voting to keep interest rates unchanged.

-

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next Move

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next MoveThe December CPI report came in lighter than expected, but housing costs remain an overhang.

-

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?The Justice Department served subpoenas on the Fed about a project to remodel the central bank's historic buildings.

-

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed Meeting

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed MeetingThe December jobs report signaled a sluggish labor market, but it's not weak enough for the Fed to cut rates later this month.