Not Every Value Stock Is a Good One

As a sector, value stocks have been hammered. But there are still plenty of good deals out there — you just have to be choosy.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

When I fell in love with the stock market many years ago, it was value investing that lured me. I became enthralled by the great value books: Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor, John Train’s The Money Masters and David Dreman’s Contrarian Investment Strategy. The message was simple: Buy low, sell high (or, better yet, not at all). What excited me was the search for excellent companies shunned by other investors. To find an overlooked stock and keep it through adversity, then to have it recognized and its price soar—now that was a thrill.

Buying growth stocks is not nearly as challenging. Jumping on the Tesla express is not my idea of excitement, and what goes way up often comes way down (see, for example, Enron). Also, the data were on my side: Value stocks clobbered growth stocks. “From 1927 to 2007,” said a JPMorgan research report earlier this year, “buying shares that were cheaper than the rest of the market (value investing) led to very significant outperformance.” The report included a chart showing that if you had put $100 in a value portfolio and $100 in a growth portfolio in 1927, the value portfolio would have grown to be about 40 times more valuable than the growth portfolio by 2007.

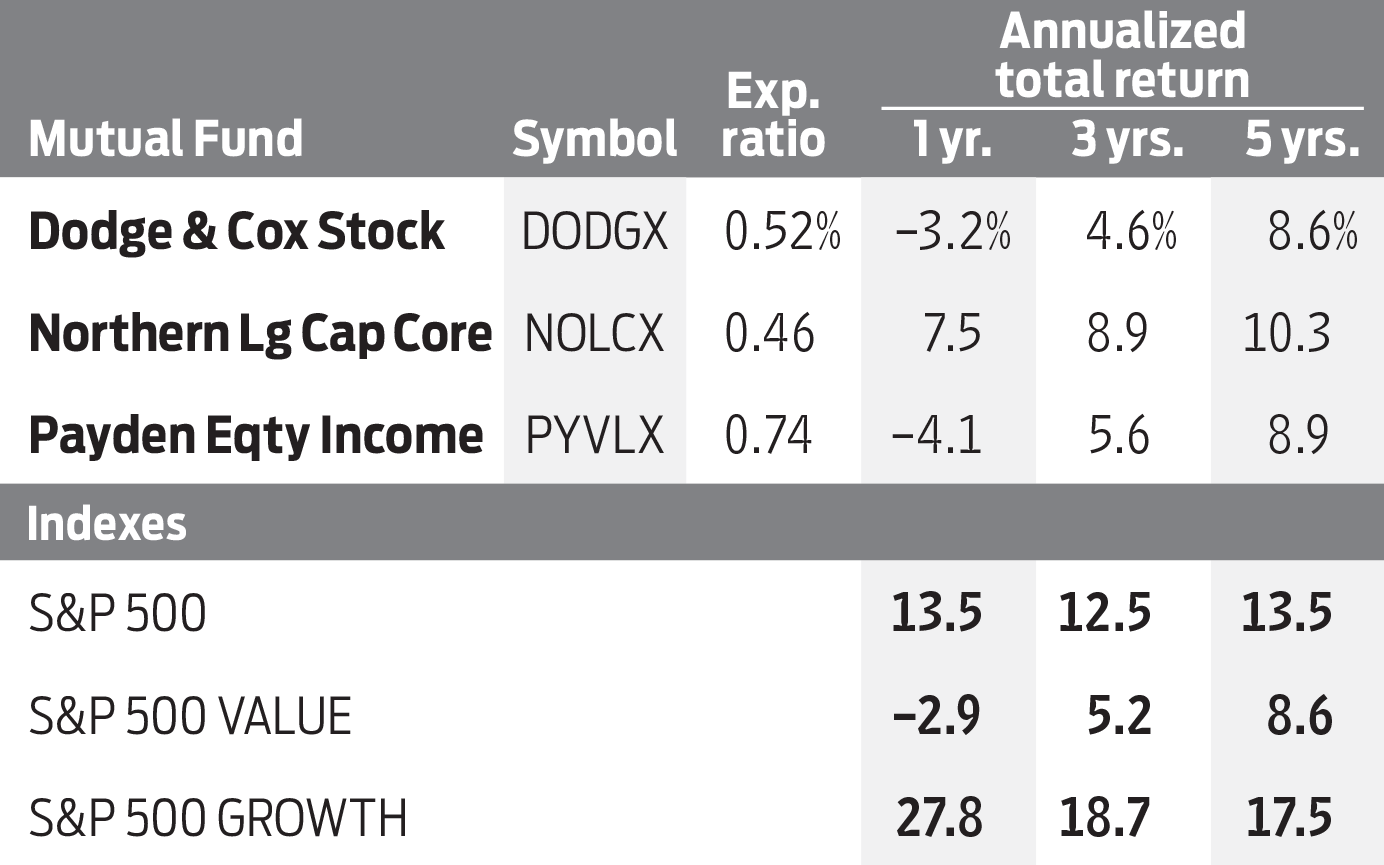

But then, the bottom dropped out. The S&P 500 Value index, determined by such valuation metrics as lower price-earnings and price-to-book ratios, has returned an annual average of just 8.6% over the past five years; the S&P 500 Growth index has returned 17.5%. And so far in 2020, it’s a rout. The Growth index has returned 18.8%, while the Value index has declined 11.0%. It’s no surprise, then, that investors have fled. Vanguard S&P 500 Growth (symbol VOOG), an exchange-traded fund linked to the index, has four times the assets of Vanguard S&P Value (VOOV). (Prices and returns are through September 11 unless otherwise noted.)

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Nobel Prize winner Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, the economists who first recognized the superiority of value stocks in 1992, have chronicled the disappearing margin but admit they don’t understand what has happened. But David Booth, a research assistant to Fama more than 50 years ago and later the founder of Dimensional Fund Advisors, an index-fund specialist with $514 billion under management, is optimistic. He believes that growth and value will come back to their historical relationship. “In my view,” Booth wrote on Marketwatch, “the rationale for investing in value stocks is as strong as ever: The less you pay for a stock, the higher your expected return.”

The slow-growth paradox. There are strong arguments, however, on the other side. The main one is that, not even taking COVID into account, the United States has been mired in slow economic growth ever since 2005, just before the value-growth divergence began. In such periods, investors are willing to pay a premium to own companies that can increase their sales and profits at a brisk pace. It may be a paradox, but growth outpaces value when the economy is sluggish. Our low long-term interest rates, signaling lackluster demand, indicate that the days of 3%-plus economic growth may be over.

Those desirable revenue and profit increases today can be found primarily among tech stocks. Despite recent declines because of the pandemic, revenues in the internet-services industry have grown at an annual average of 22.1%, and net income has grown at an annual average of 21.8%, over the past five years through the second quarter of this year. An incredible 42% of the assets of the S&P 500 Growth index are held in information technology stocks, compared with just 8% for the Value index. Many value stocks, on the other hand, populate out-of-favor sectors such as finance and energy.

Tech stocks are powering the growth indexes. The five largest companies in the Vanguard S&P 500 Growth ETF, all in tech, account for three-eighths of the total value of the fund. Apple alone, the number-one stock in the portfolio at last report, has returned 53% this year, even after taking some knocks lately. So perhaps the divergence between growth and value is simply a story of huge increases in tech stock prices—a phenomenon we saw before in the late 1990s. And you remember how that story ended.

Many value stocks have become so detested that they have, in effect, become super-value stocks. Although strange anomalies can occur in the short term, historical patterns tend to continue over the long term. Also, many value stocks are paying attractive dividends at a time when 10-year Treasuries are yielding well under 1%. Finally, anyone who prefers cheap to dear has to recognize that there are superb bargains out there. The best place to find them is among mutual funds managed by good stock pickers.

Payden Equity Income (PYVLX) has notched an annual average return of 8.9% over the past five years with considerably lower volatility than the market as a whole. Unfortunately, it requires a $100,000 initial investment, unless you purchase shares through an adviser. Still, you can always check out the portfolio for ideas. Among the top holdings are some excellent choices, including the defense aerospace giant Lockheed Martin (LMT, $389), whose shares are flat this year and trade at a P/E of just 15 (based on expected earnings for the next 12 months) with a 2.5% dividend yield. Others are JPMorgan Chase (JPM, $101), the largest U.S. bank, with a P/E of 14 and a yield of 3.6%, and, yes, a tech company, internet-infrastructure specialist Cisco Systems (CSCO, $40), with a P/E of 13 and a yield of 3.6%.

The portfolio of Dodge & Cox Stock (DODGX), a longtime favorite of mine and a member of the Kiplinger 25 list of favorite no-load funds, has extremely low turnover and a modest expense ratio of just 0.52%. It is overweighted in financials, including Bank of America (BAC, $26), Wells Fargo (WFC, $24), Bank of New York Mellon (BK, $36) and American Express (AXP, 103). In the financial sector, as with others disrupted by COVID, current and projected short-term earnings aren’t particularly meaningful. In these cases, I prefer to look backward. For example, if Bank of America reverts to its 2019 earnings in 2022, then its P/E today on that basis would be just 9.

Dodge & Cox also owns two value-oriented tech stocks: HP (HPQ, $19), with a very un-tech-like yield of 3.7%, and Dell Technologies (DELL, $66). HP has rebounded from its March lows but not in the spectacular manner of Apple and its cohorts. Dell carries a forward P/E of just 11. The fund has a substantial 9% of its assets in the energy sector, recently adding to its holdings of Occidental Petroleum (OXY, $10), an oil and gas exploration company whose stock is down more than 70% since the start of the year.

Northern Large Cap Core (NOLCX), which has returned 10.3% annualized over the past five years and charges yearly expenses of 0.46%, is officially rated a large-cap value fund by Morningstar, but its portfolio is larded with tech growth companies, including Apple and Alphabet. Also on the list are classic value stocks, including AT&T (T, $29), yielding 7.2% with a P/E of 9. A yield that high is always suspect, because it sometimes indicates a dividend cut is at hand, but I believe it is safe. Additional Northern holdings to consider are Merck & Co. (MRK, $84), the pharmaceutical giant, and PepsiCo (PEP, $136), the beverage company.

My preference is to avoid value stocks as a category—that is, stay away from index funds—but pick and choose among individual stocks and managed funds. There are great companies out there at low prices, and you can collect good dividends while you wait for other investors to catch up.

James K. Glassman chairs Glassman Advisory, a public-affairs consulting firm. He does not write about his clients. His most recent book is Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments In a Time of Turbulence. He owns shares in Bank of America.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

QUIZ: Are You Ready To Retire At 55?

QUIZ: Are You Ready To Retire At 55?Quiz Are you in a good position to retire at 55? Find out with this quick quiz.

-

10 Decluttering Books That Can Help You Downsize Without Regret

10 Decluttering Books That Can Help You Downsize Without RegretFrom managing a lifetime of belongings to navigating family dynamics, these expert-backed books offer practical guidance for anyone preparing to downsize.

-

New Ways to Keep Online Accounts Safe

New Ways to Keep Online Accounts SafeAs cybercrime evolves, the strategies you use to protect yourself need to evolve, too.

-

The Most Tax-Friendly States for Investing in 2025 (Hint: There Are Two)

The Most Tax-Friendly States for Investing in 2025 (Hint: There Are Two)State Taxes Living in one of these places could lower your 2025 investment taxes — especially if you invest in real estate.

-

Bond Basics: Zero-Coupon Bonds

Bond Basics: Zero-Coupon Bondsinvesting These investments are attractive only to a select few. Find out if they're right for you.

-

Bond Basics: How to Reduce the Risks

Bond Basics: How to Reduce the Risksinvesting Bonds have risks you won't find in other types of investments. Find out how to spot risky bonds and how to avoid them.

-

What's the Difference Between a Bond's Price and Value?

What's the Difference Between a Bond's Price and Value?bonds Bonds are complex. Learning about how to trade them is as important as why to trade them.

-

Bond Basics: U.S. Agency Bonds

Bond Basics: U.S. Agency Bondsinvesting These investments are close enough to government bonds in terms of safety, but make sure you're aware of the risks.

-

Bond Ratings and What They Mean

Bond Ratings and What They Meaninvesting Bond ratings measure the creditworthiness of your bond issuer. Understanding bond ratings can help you limit your risk and maximize your yield.

-

Bond Basics: U.S. Savings Bonds

Bond Basics: U.S. Savings Bondsinvesting U.S. savings bonds are a tax-advantaged way to save for higher education.

-

Bond Basics: Treasuries

Bond Basics: Treasuriesinvesting Understand the different types of U.S. treasuries and how they work.