Emerging Markets Picks

Cash in by investing in companies that benefit from rising demand in their own domestic markets.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

During the past decade, emerging markets truly emerged. If at the start of 2000 you had put $10,000 into Vanguard 500 Index (symbol VFINX), a mutual fund that tracks the stocks of large U.S. companies, you would have had $9,016 at the end of 2009. But if you’d invested $10,000 in Vanguard Emerging Markets Stock Index (VEIEX), your investment would have grown to $25,516.

Emerging-markets stocks are doing well because the economies of the countries where those companies are based are flourishing. The recession ended last year for most of the world, but the economies of developed nations still appear anemic. The Economist magazine projects that gross domestic product in Germany will grow just 1.6% in 2010; in Britain, the Netherlands and France, 1.3%; and in Japan, 1.5%. GDP in the U.S. is expected to grow 2.7%, but that is no great shakes coming out of a terrible recession. By contrast, The Economist forecasts that about two-thirds of the 21 Asian, Middle Eastern and Latin American economies it tracks will produce growth of at least 3%. It sees economic growth this year at 8.6% for China, 6.3% for India and 4.5% for Indonesia.

In fact, I think it’s time to stop using terms such as emerging and developing to describe the dichotomy of the world’s economies. Instead, I propose to start calling fast-growing, developing nations aspiring (as in doing their best to excel) and call Europe, Japan and the U.S. mature (as in topping out).

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Capital-rich. Economic growth in aspiring nations is likely to remain robust for the next decade and beyond. Why am I so confident? For starters, these economies now have the capital -- both homegrown and attracted from abroad -- to start new businesses and build existing ones. In the first nine months of 2009, Chinese banks made $1.3 trillion worth of new loans around the world. Beneficiaries of this largess include mature-economy companies, such as Southwest Airlines and the Woolworths supermarket chain in Australia.

Plus, governments in aspiring nations are promoting growth-oriented policies. India, for instance, is simplifying its tax system for businesses in what could be the “single most important initiative in the fiscal history” of the country, according to a paper by Satya Poddar, of Ernst & Young, and Ehtisham Ahmad, of the London School of Economics.

Finally, the ratio of young workers to retirees is more favorable in aspiring countries. For example, only 6% of Indonesians are over 65, compared with 16% in France and 22% in Japan.

Aspiring economies are attractive on both the supply side and the demand side of the economic equation. On the supply side, natural resources are plentiful, labor is cheaper than in mature markets, and workers are becoming more efficient as education levels rise and more capital is invested. But change on the demand side is even more dramatic. With incomes growing, the citizens of aspiring economies are moving beyond the necessities. They’re eating better food, buying their own homes and purchasing cars, among other things.

In the past, supply-side companies -- most of them global exporters -- dominated the attention of investors. But a better way to cash in on aspiring economies is by investing in companies that benefit from rising demand in their own domestic markets. As I pointed out in my February column, the three top performers among U.S.-listed stocks over the past ten years are all based in Brazil and cater to the local market. For instance, the number-one stock, Banco Bradesco (BBD), serves the nation’s low- and moderate-income families and small businesses.

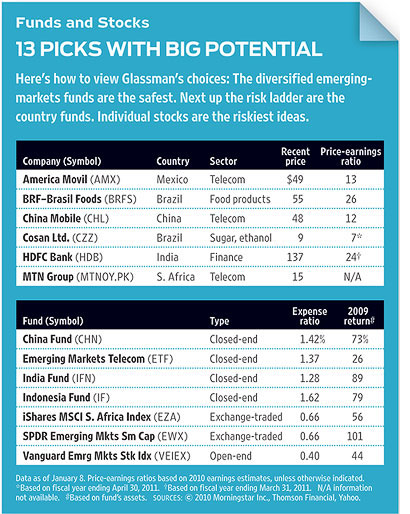

Another domestic Brazilian play is BRF–Brasil Foods (BRFS), a 110-year-old company that sells meat, pizzas, desserts and other food products. Business is booming; in the third quarter of 2009, revenues rose 74% from the same period a year earlier. The downside: The stock has nearly doubled in the past year, and it’s not inexpensive. Also consider Cosan Ltd. (CZZ), a producer of sugar as well as of ethanol for transportation. Shares of Cosan nearly tripled last year, but they remain well below their 2008 highs and, at a bit less than $9 a share, sell for just seven times earnings, based on estimated profits for the year that ends April 2011. Like Banco Bradesco, both stocks trade on the New York Stock Exchange.

If you want to go further afield, look at Indonesia, the world’s fourth most-populous country (after China, India and the U.S.). Intriguing choices include PT Ace Hardware Indonesia, a home-improvement retailer with 36 outlets, and Mandom Indonesia, which makes cosmetics and perfumes -- the sort of products whose sales accelerate as incomes rise. Both stocks trade only on the Jakarta exchange, but you can purchase pieces of them by investing in the Indonesia Fund (IF), a closed-end fund that owns about two dozen Indonesian companies. (The fund charges a hefty expense ratio of 1.62%; in mid January, it traded at a 4% discount to the value of its underlying assets.)

Similarly, you can purchase shares of the closed-end China Fund (CHN), which has a strong domestic tilt in its 52-stock portfolio. Among the holdings are Wumart Stores (that’s no misprint), with 500 retail outlets, mostly convenience stores, and Ports Design, which sells men’s and women’s fashion garments, mainly in China. China Fund recently traded at a 4% discount to the value of its assets. Or consider Matthews India (MINDX), a conventional open-end fund that returned 97% in 2009. It owns shares in such companies as Dabur India, which makes natural health-care products that appeal to Indians, and Sun TV Network, which broadcasts in the regional languages of South India.

The most straightforward demand-side sectors in aspiring economies are telecommunications and commercial banking, which serve almost as toll takers on general consumer activity. MTN Group (MTNOY.PK), based in South Africa, offers cellular service to 108 million subscribers in 21 countries in Africa and the Middle East, including Syria and Iran. MTN’s American depositary receipts trade on the pink sheets. MTN is the top holding of Emerging Markets Telecommunications (ETF), a closed-end fund that owns three dozen telecom stocks and gives investors a way to gain exposure to such aspiring economies as Egypt, China and the Philippines. It traded at an 11% discount recently.

Although its local telephone business is faltering, the number of Internet accounts with Telefonos de Mexico (TMX) jumped 45% in the past 12 months. America Movil (AMX), also based in Mexico, is the largest provider of wireless communications in Latin America, with 194 million subscribers in 17 countries. And then there’s China Mobile (CHL), China’s largest wireless provider, with more than 500 million customers and a market value larger than that of AT&T or Verizon.

For banking, search out companies such as India’s HDFC Bank (HDB), with 1,400 branches; China Merchants Bank (CIHHF.PK), which recently announced it would expand lending to small businesses; and Standard Bank Group (SBGOY.PK) of South Africa, which is available in the U.S. as an American depositary receipt.

What’s more aspirational than a fast-growing small company? With stocks of companies on both the supply and demand sides, SPDR S&P Emerging Markets Small Cap (EWX), an exchange-traded fund with a modest expense ratio of 0.66%, owns a portfolio of 256 stocks, including Charoen Pok Foods, a Thai food processor; Turk Hava Yollari, an air-transport and cargo-service provider based in Turkey; and Empresas La Polar, S.A., which sells a wide range of consumer goods, including appliances and toys, in Chile.

Even with so much going for them, shares of firms in aspiring economies can be highly volatile -- and many stocks today are vulnerable to declines after big gains in 2009. For the long run, however, aspiring investors need these companies. They’re where the growth is, now and in the decades ahead.

James K. Glassman is executive director of the George W. Bush Institute in Dallas. His next investing book appears later this year. Of the securities mentioned, he owns shares in the China Fund.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Find Joy and Meaning When You Want to Retire — But Can’t Yet

Find Joy and Meaning When You Want to Retire — But Can’t YetFor Gen X, delaying retirement can be an opportunity to pilot-test your second act, plan for your inheritance and structure trusts for your kids.

-

My First $1 Million: Banking Executive, 37, Nashville

My First $1 Million: Banking Executive, 37, NashvilleEver wonder how someone who's made a million dollars or more did it? Kiplinger's My First $1 Million series uncovers the answers.

-

Small Splurges That Won't Derail Your Retirement

Small Splurges That Won't Derail Your RetirementWith decades of growth ahead, your 40s aren't just for saving. We asked financial advisers how to enjoy your income now without compromising your nest egg.

-

White House Probes Tracking Tech That Monitors Workers’ Productivity: Kiplinger Economic Forecasts

White House Probes Tracking Tech That Monitors Workers’ Productivity: Kiplinger Economic ForecastsEconomic Forecasts White House probes tracking tech that monitors workers’ productivity: Kiplinger Economic Forecasts

-

Investing in Emerging Markets Still Holds Promise

Investing in Emerging Markets Still Holds PromiseEmerging markets have been hit hard in recent years, but investors should consider their long runway for potential growth.

-

5 Big Tech Stocks That Are Bargains Now

5 Big Tech Stocks That Are Bargains Nowtech stocks Few corners of Wall Street have been spared from this year's selloff, creating a buying opportunity in some of the most sought-after tech stocks.

-

Stocks: Winners and Losers from the Strong Dollar

Stocks: Winners and Losers from the Strong DollarForeign Stocks & Emerging Markets The greenback’s rise may hurt companies with a global footprint, but benefit those that depend on imports.

-

How to Invest for a Recession

How to Invest for a Recessioninvesting During a recession, dividends are especially important because they give you a cushion even if the stock price falls.

-

5 Exciting Emerging Markets Funds to Buy

5 Exciting Emerging Markets Funds to BuyForeign Stocks & Emerging Markets Emerging markets funds haven't been immune to global inflationary pressures. But now might be the time to strike on these high-risk, high-reward products.

-

10 Stocks to Buy When They're Down

10 Stocks to Buy When They're Downstocks When the market drops sharply, it creates an opportunity to buy quality stocks at a bargain.

-

How Many Stocks Should You Have in Your Portfolio?

How Many Stocks Should You Have in Your Portfolio?stocks It’s been a volatile year for equities. One of the best ways for investors to smooth the ride is with a diverse selection of stocks and stock funds. But diversification can have its own perils.