What to Do With Cash in Hand

Use these strategies to make sure your money is safe, earns a decent rate and is accessible.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Readers who imagine I'm preoccupied with over-engineered income securities and bond market fiascos deserve a break. So here's a simpler subject: If you have cash in hand, what's the safest and wisest way to hold it?

I owe this idea to a man in his forties from Ohio. I'll call him Scott. Scott wrote to say he has $50,000 in a bank account that pays 2% before taxes. He wants a better return and full liquidity with no risk -- don't we all? -- he calls himself "clueless" about his choices. Scott has substantial 401(k) and IRA investments, and he's not spending the income, so this $50K isn't meant for high-dividend stocks or oil trusts. It's the all-purpose cash reserve that's subject to surprise raids when you have two teenagers and own eight rental properties, as Scott does.

If this were June 2007, my advice on this question would be obvious: Find a money-market fund with low expenses. One of the most efficient, Vanguard Prime Money Market (symbol VMMXX), requires $3,000 to open but then lets you add $100 at a time. It charges nothing to write checks or transfer money to a bank account. Its annual expense ratio is a low 0.24%. In June, 2007, the fund yielded 5.1%.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Most of us would do cartwheels if we could get a no-risk yield of that size today. But because of a series of short-term interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve Board, the Vanguard fund now yields just 2.2%. That grosses you an extra $100 a year on a $50,000 bank balance that's making 2%.

With money-market fund yields in the gutter, the investment business has been promoting products that pay more than money funds but aren't as safe. These products, which we'll call cash-plus investments, include funds that own short-term pieces of bank loans, ultra-short-term bond funds, stable value funds, and private, or non-traded, real estate investment trusts. The premise, if not the promise, of cash-plus products is that their prices won't vary by more than a few pennies per share, making them effectively higher-paying versions of money-market funds, short-term certificates of deposit and savings accounts -- the values of which aren't supposed to fluctuate even by a hair.

Until 2007's credit-market upheavals, I'd have unequivocally endorsed all these categories except the non-traded REITs (those REITs are among the silliest ideas ever foisted on the individual investor because they don't allow you to benefit from rising real estate values, which over time rise at least as much as inflation).

But, starting last summer, a number of cash-plus products struck land mines. Fidelity and Charles Schwab have had disasters with their ultra-short bond funds. The average bank-loan fund has lost 4% over the past year on a total-return basis, which means that their share prices have fallen far more. Although bank-loan funds have recovered some of their losses since the Federal Reserve began to address the credit crisis aggressively in March, they can no longer be considered safe havens for money you can't afford to lose.

So, to answer Scott from Ohio and everyone else whose bank doesn't pay them enough interest to buy bread and milk, I asked the members of the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors to tell me their favorite strategies and vehicles for short-term cash. In two days I got nearly 50 replies, and, as I expected, the counselors, all fee-only planners, agreed that this isn't the time to take chances with cash reserves.

Their preferences are money-market funds, online savings accounts and short-term CDs and government debt. That would include debt securities maturing in two years or less issued by such entities as the Federal Home Loan Banks, the Farm Credit Banks, or Fannie Mae. I'll name some specific favorites of mine later in this column.

But first, there are strategies and tricks to help you get the best out of a conservative mix and guarantee as best as possible that you'll stay away from unexpected troubles.

1. Break it up. It's safe to put up to $100,000 (per depositor) in a single FDIC-insured bank account, but most of the better-paying cash investments aren't insured or found at banks. So, in the interest of safety and common sense, spread your cash around several places, not all of which need be banks. One ladder of bank CDs, two money funds and one or two short-term government gency bonds make a sensible combination. I don't think a Vanguard or a Fidelity or a T. Rowe Price money fund will implode and lose principal value, but nor would I have imagined that Fidelity Ultra-Short Bond fund (FUSFX) could lose 13% in one year unless an insider stole the shareholders' money and absconded to Mars. So split your savings up several ways if you can. It's not hard to do.

2. Think ahead to higher rates. If you're a CD person, keep maturities short so you'll have money to roll over at a better rate as soon as this winter. The Federal Reserve influences short-term interest rates, and these rates are likely to start heading higher by year's end. To prevent the economy from going into recession and to deal with the credit crisis, the Fed reduced rates repeatedly in 2007 and 2008. The Fed is now becoming increasingly concerned about rising inflation and the falling dollar, which has inflationary implications, so its next move will almost surely be to raise the Federal funds rate. That will lead to higher short-term savings rates.

3. Don't make unsecured loans to troubled financial institutions. Some exchange-traded notes, as well as some bank-loan and ultra-short bond funds, list as assets a bunch of short-term cash advances to the likes of Lehman Brothers or Citibank and, not long ago, to Bear Stearns. There's no reason to think a Lehman or a Citi or other big institutions will go the way of Bear, but why take the extra risk for a few extra shavings of interest?

4. Say no to high expenses. In a low-yielding world, where a good money fund pays you less than 2.5%, it's ludicrous to lose even half of a percentage point to expenses. Contrary to what you might think, it does take management skill to run a money fund or a short-term Treasury fund. But one reason Vanguard's fund pays more than most is that it costs you less than 0.25% to be a customer. At Putnam Investments, the money-market fund comes in six share classes with expenses ranging from 0.54% to a withering 1.04%. Just say no, or heck no, to any money fund that charges more than 0.50% a year. It's not hard one that charges half of that.

5. Look online. Virtual banks' savings accounts still pay nicely. Even your own bank may make a distinction between what it pays at the branch and what it does on the Internet. A standard savings account at M&T Bank, a major consumer bank in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states, pays 0.25% on a regular savings that's linked to your checking account. But M&T's e-savings gives you 3.25%.

Now that you have some idea of how to get the best out of what you might dismiss as an inconsequential decision, let's go back to the experts from Napfa and see who suggested what.

If I were to give the Cash in Hand Silver Dollar Medal for the best combination, I'd give it to William M. Howell, of Howell Financial Advisors in Noblesville, Ind. (Personal note: My dear late mother-in-law was raised in Noblesville, a town just north of Indianapolis). Howell's suggestion: 10% to 20% in a bank account, defined as anything FDIC insured. He didn't specify online or in person, but do try to get 3%, which is more likely achievable online.

Half of the balance in short-term bank CDs, divided between three-month and six-month maturities. Right now a three-month CD at a competitive bank (check our Credit & Money Management page for rates) gets you about 3.1% and a six-month CD 3.3%. It's a pretty good bet that when it's time to roll these over, you'll get at least another 0.25 percentage point and maybe twice that extra.

The other half of the remainder goes in a high-quality low-cost money fund like the Vanguard Prime Money Market.

This combo gets you FDIC backing on most of the money, instant liquidity through checks on the money-market fund, online transfers from the online savings account to your checking account, and the security of knowing that you haven't put all of your savings in one place or any of it in something funky you don't understand.

Joel Shaps, of Bedrock Capital Management in Los Altos, Calif., gets second prize. Shaps says that short-term government agency bonds are safe and deserve consideration when their yields are more than a money fund's by enough to matter. In the second week of June, you could get 2.7% for one year from the Farm Credit Banks and 4.3% for three years. A three-year IOU isn't a cash substitute, but the shorter agency paper beats a money-market fund by about half a percentage point. You might watch to see if and when the Farm Credit Banks or Federal Home Loan Banks yields exceed 3%. It could happen before CDs do. If you have a good online brokerage account, you can follow these rates easily and invest as little as $1,000 in new issues.

Okay, Scott from Ohio, we just got you from 2% to about 3% with no risk and little fuss. That's $500 a year before taxes. Too bad it won't buy much more than a few tanks of gas, but $500 isn't chopped liver, either.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Kosnett is the editor of Kiplinger Investing for Income and writes the "Cash in Hand" column for Kiplinger Personal Finance. He is an income-investing expert who covers bonds, real estate investment trusts, oil and gas income deals, dividend stocks and anything else that pays interest and dividends. He joined Kiplinger in 1981 after six years in newspapers, including the Baltimore Sun. He is a 1976 journalism graduate from the Medill School at Northwestern University and completed an executive program at the Carnegie-Mellon University business school in 1978.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

AI Sparks Existential Crisis for Software Stocks

AI Sparks Existential Crisis for Software StocksThe Kiplinger Letter Fears that SaaS subscription software could be rendered obsolete by artificial intelligence make investors jittery.

-

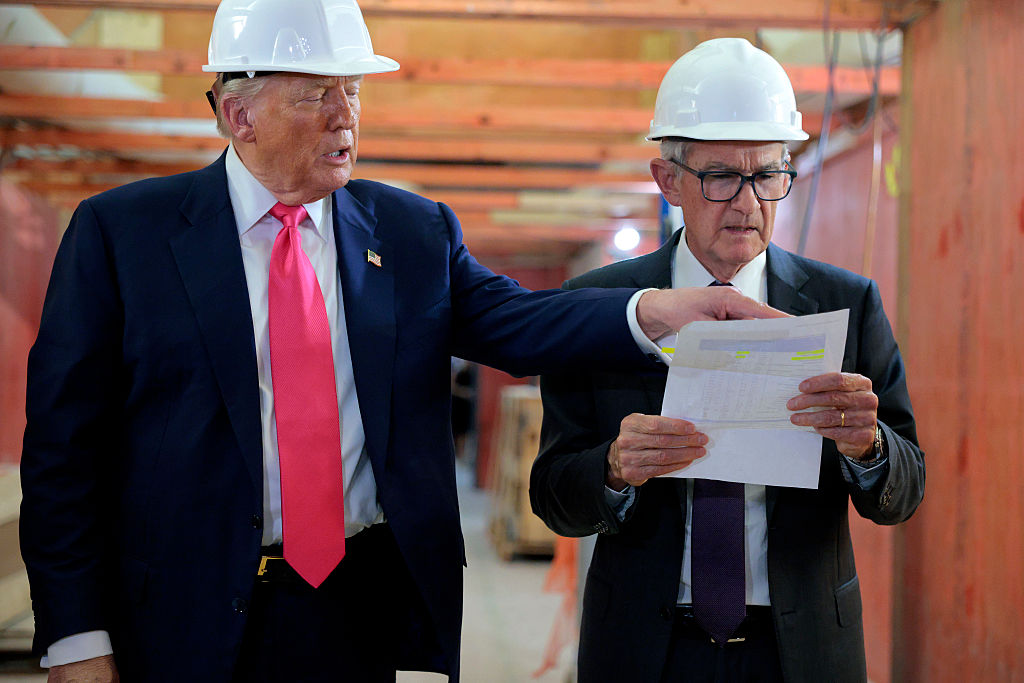

Big Change Coming to the Federal Reserve

Big Change Coming to the Federal ReserveThe Lette A new chairman of the Federal Reserve has been named. What will this mean for the economy?

-

Job Growth Sizzled to Start the Year. Here's Why It's Unlikely to Impact Interest Rates

Job Growth Sizzled to Start the Year. Here's Why It's Unlikely to Impact Interest RatesThe January jobs report came in much stronger than expected and the unemployment rate ticked lower to start 2026, easing worries about a slowing labor market.

-

Why the Next Fed Chair Decision May Be the Most Consequential in Decades

Why the Next Fed Chair Decision May Be the Most Consequential in DecadesKevin Warsh, Trump's Federal Reserve chair nominee, faces a delicate balancing act, both political and economic.

-

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to Know

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to KnowPresident Donald Trump announced Kevin Warsh as his selection for the next chair of the Federal Reserve, who will replace Jerome Powell.

-

January Fed Meeting: Updates and Commentary

January Fed Meeting: Updates and CommentaryThe January Fed meeting marked the first central bank gathering of 2026, with Fed Chair Powell & Co. voting to keep interest rates unchanged.

-

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next Move

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next MoveThe December CPI report came in lighter than expected, but housing costs remain an overhang.

-

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?The Justice Department served subpoenas on the Fed about a project to remodel the central bank's historic buildings.

-

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed Meeting

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed MeetingThe December jobs report signaled a sluggish labor market, but it's not weak enough for the Fed to cut rates later this month.