Gamblers Are Surprisingly Accurate at Picking the Next President

Polls show a tight race for the White House, but betting sites have the odds firmly favoring Clinton.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Forget the polls. If you want to know who will win the presidential election on November 8, look at how the gamblers are placing their bets

The polls predict a squeaker. Real Clear Politics' average of polls has Hillary Clinton leading Donald Trump by less than two percentage points. But the betting markets—online securities exchanges where individuals can wager on elections—give Clinton roughly two-to-one odds to win, and one exchange, the Iowa Electronic Markets, predicts that she’ll win by a comfortable seven percentage points.

Why should you care what the bettors are thinking? Because their record in past elections has generally been more accurate than that of the pollsters. In 2012, both the final national polls and the betting markets had Mitt Romney and Barack Obama essentially tied for the popular vote. But the betting markets never wavered that Obama would win, while the polls favored Romney during the first half of October. Plungers on Intrade, a now-defunct Irish betting site, called 49 of 50 states correctly in 2012 and nailed 47 states in 2008.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Betting on elections in the U.S. is generally illegal. But gamblers in Europe bet heavily on U.S. elections, mainly via a London-based site called Betfair, and two small U.S. election betting sites operate under waivers granted by federal regulators. More on these sites in a moment.

Gamblers have an edge over pollsters, says David Rothschild, a Microsoft researcher who runs PredictWise.com, a site that incorporates data from gamblers, pollsters and other sources, including social media. That’s because gamblers typically study the polls but also pay attention to other factors, such as the state of the economy and the effectiveness of each campaign’s get-out-the-vote effort, in their decision-making. After all, when you actually put your money where your mouth is, you tend to be careful. Rothschild’s site puts a heavy emphasis on the gambling markets, one that increases as Election Day nears. On the heels of the first presidential debate, he gives Clinton a 70% chance of victory.

In the U.S., the Iowa Electronic Markets is the granddaddy of these exchanges. Formed by business professors at the University of Iowa in 1988 for students and teachers to wager on that year’s presidential election, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission licensed IEM to take bets from the public on subsequent elections because of its academic purpose—but the commission put a $500 limit on an individual’s “investments.”

The Iowa market’s results have been striking. That market has generally been more accurate than polls in a wide swath of executive, legislative, national and local elections. A 2008 study by three University of Iowa researchers found that the Iowa market was more accurate than 74% of the 964 presidential polls conducted during the five elections between 1988 and 2008.

The betting markets are far from infallible. This year, in particular, they’ve hit potholes. Most striking were the failure of online-exchange gamblers and London bookies to get the Brexit vote right last summer and the failure of the betting markets to anticipate Trump’s nomination to head the Republican ticket. Most pollsters, meanwhile, accurately predicted both events.

But that’s no reason to ignore these markets. After all, when the betting markets predict, as they were as of this writing, that Trump has a roughly one-in-three chance of being elected president, that’s not a trivial possibility. As everyone who has ever played the ponies knows, sometimes a 50-1 long shot wins. And Trump is hardly a long shot at this point in the campaign, and, of course, things could change quickly for many reasons including the outcomes of the remaining presidential debates.

Interested in investing in the election markets? PredictIt.org is easy to navigate and takes credit cards, so you can sign-up quickly online. You can bet up to $850 on each of its many markets. The bad news on PredicIt is in the fine print: The site charges a 5% “processing fee” on your investment and takes 10% of any winnings. Ouch! (Full disclosure: I've placed wagers on a Clinton victory on this site.)

The Iowa market charges a mere $5 fee to open an account. But the website, in the midst of a much-needed update, is a bit confusing to navigate. Plus, you have to mail in a check before you can place a bet.

Historically, gambling on election outcomes was common in the U.S. It predated polling, which didn’t catch on until the 1930s. By the late 1800s, semi-formal election markets operated, and newspapers published the odds daily. Gamblers wagered some $220 million in today’s dollars on the 1916 presidential election. What’s more, the betting markets proved accurate in all but one of the presidential elections from 1884 to 1940 in which bettors established a clear favorite by mid-October, researchers found. But in the 1940s, New York City, where the election gambling was centered, cracked down on unauthorized gambling, and it went underground.

Now it’s back, albeit on a small scale. And it’s worth paying attention to if you want to know who’s going to win the White House. Not that you should ignore the polls. My advice: To have the most accurate perspective on the race, consult PredictWise.com and, for the best polling analysis, click on Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight election forecast.

Steve Goldberg is an investment adviser in the Washington, D.C., area.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're Rich

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're RichSome frugal habits are worth it, no matter what tax bracket you're in.

-

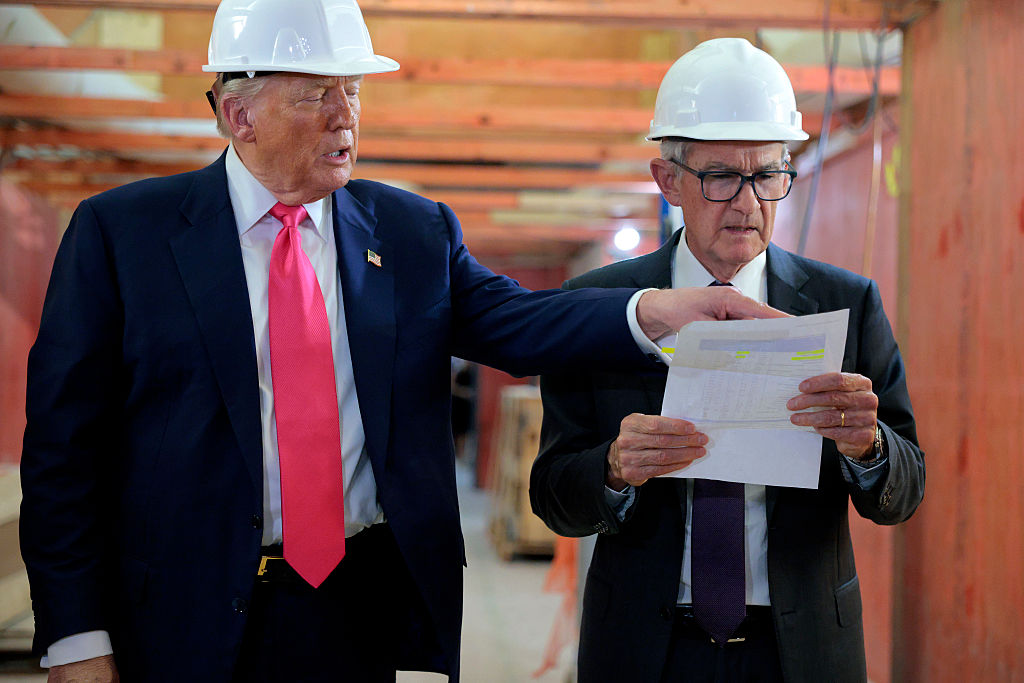

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to Know

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to KnowPresident Donald Trump announced Kevin Warsh as his selection for the next chair of the Federal Reserve, who will replace Jerome Powell.

-

January Fed Meeting: Updates and Commentary

January Fed Meeting: Updates and CommentaryThe January Fed meeting marked the first central bank gathering of 2026, with Fed Chair Powell & Co. voting to keep interest rates unchanged.

-

Trump Reshapes Foreign Policy

Trump Reshapes Foreign PolicyThe Kiplinger Letter The President starts the new year by putting allies and adversaries on notice.

-

Congress Set for Busy Winter

Congress Set for Busy WinterThe Kiplinger Letter The Letter editors review the bills Congress will decide on this year. The government funding bill is paramount, but other issues vie for lawmakers’ attention.

-

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next Move

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next MoveThe December CPI report came in lighter than expected, but housing costs remain an overhang.

-

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?The Justice Department served subpoenas on the Fed about a project to remodel the central bank's historic buildings.

-

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026The Kiplinger Letter Here are some of the biggest events and trends in economics, politics and tech that will shape the new year.

-

Special Report: The Future of American Politics

Special Report: The Future of American PoliticsThe Kiplinger Letter The Political Trends and Challenges that Will Define the Next Decade