Protect Your Parents From Scams

Follow these steps to lower the chances that your mom or dad will become victims.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

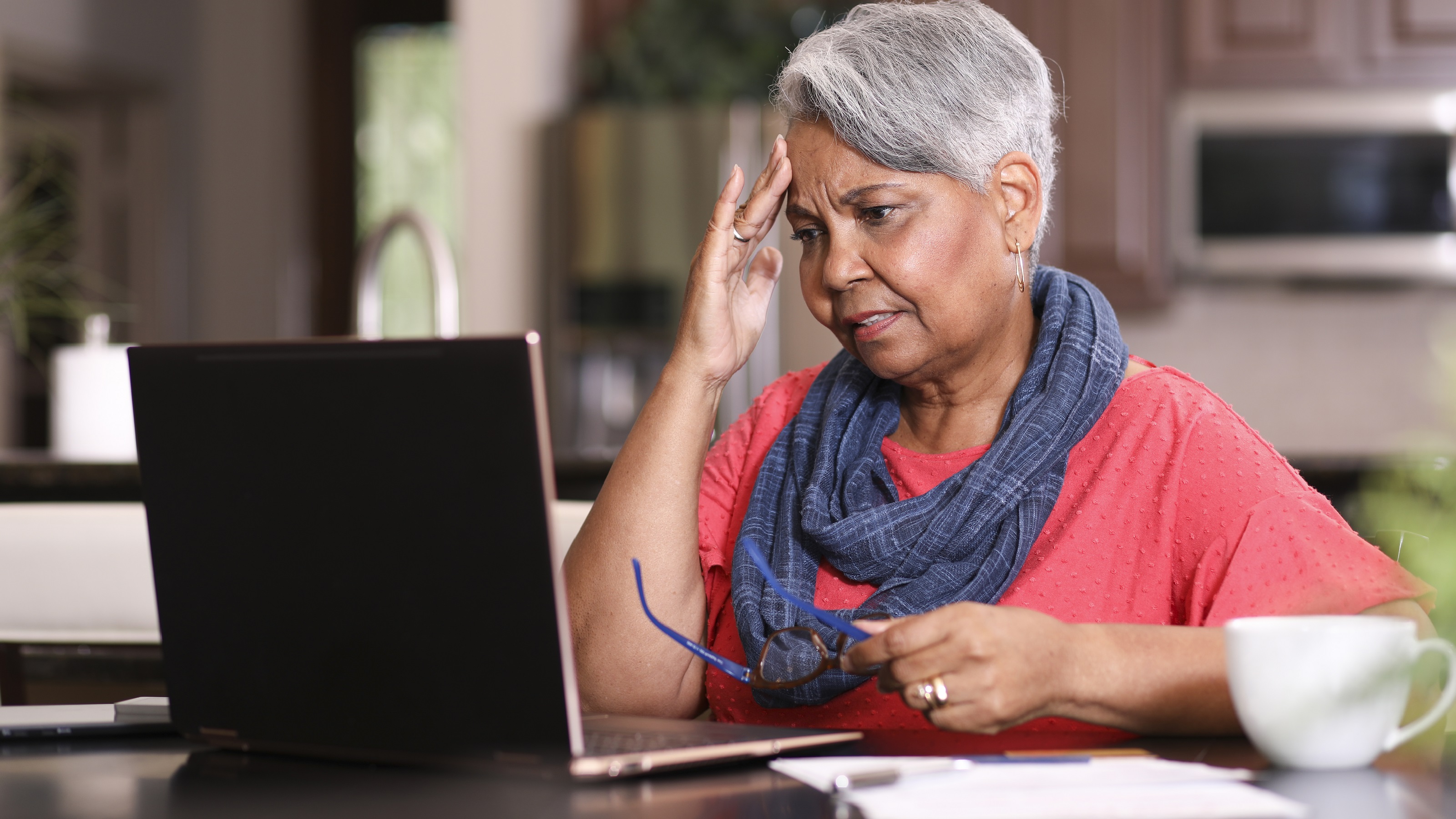

Kim Lankford in her Ask Kim column today writes about how to protect parents from elder investment fraud. Unfortunately, getting pressured into inappropriate investments isn’t the only way seniors are taken advantage of financially.

For example, my mom -- who has Alzheimer’s disease -- almost became the victim of a con artist who wanted her to wire him money to claim a “prize” she allegedly won (see Scams, Scams Everywhere). After my mom almost was scammed, I got her a phone with caller ID and told her to let calls from numbers she didn’t recognize go to voicemail. So far, this has helped my mom avoid telephone pitches from scammers.

Clearly, relying on caller ID alone won’t protect my mom. There are several other steps that I have taken and that financial planners and eldercare specialists recommend to protect older adults, especially those with dementia, from being taken advantage of by con artists, high-pressure sales people and even legitimate groups.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Put your parents on do-not-call lists. Most telemarketers will stop calling once a number has been on the National Do Not Call Registry for 31 days. You can register home and cell phone numbers for free at donotcall.gov or by calling 888-382-1222.

Monitor their mail. Tell your parents that you’ve heard about scams targeting seniors and that you want to help protect them, says Linda Fodrini-Johnson, president of the National Association of Professional Geriatric Care Managers. If you live in the same town, ask them to collect their mail during the week so that you can go through it and write checks together. Otherwise, ask a trusted friend or your parents’ eldercare provider (see The Long-Distance Caregiver) to help weed out questionable mail and requests for money.

Limit charitable giving. “A mailbox stuffed with charitable donation requests is a red flag” that your parents are susceptible to pleas for money and likely have given a lot already, says Greg Merlino, a certified financial planner and president of Ameriway Financial Services in Voorhees, N.J. However, you don’t want to stop your parents’ charitable donations entirely if that is something that has been important to them throughout their lives. Fodrini-Johnson suggests that you help your parents develop a giving plan that allows them to make donations but only to one or two organizations that matter most to them.

Monitor their accounts. Look at bank and credit-card statements with your parents and ask about questionable payments. If you already have key information about their accounts and have power of attorney, become a joint account holder so you can receive bank statements or set up online banking (if your parents haven" target="_blank">www.annualcreditreport.com to make sure they aren’t victims of identity theft.

Limit access to cash and credit. This is the toughest step to take and is geared more to people whose parents have dementia and need a lot of help managing their finances. You can start by setting up automatic payments for regular bills to reduce the number of checks that need to be written. If you have access to your parent’s checking account, limit the amount of money in it by regularly transferring funds to a savings or money-market account. Give your parents a secured credit card, which allows them to make a deposit that becomes their credit limit, and take away the other cards.

In cases where your parents really are being taken advantage of, consider giving them a cash allowance, says Carlo Panaccione, a certified financial planner and president of Navigation Group in Redwood Shores, Calif. “A lot of people will avoid it because they are afraid of conflict with their parents,” Panccione says. “What’s the alternative? Let them go until they have nothing left?” To make it easier, don’t call it an allowance -- call it a spending plan. Tell your parents you’re giving them a certain amount each week or month to spend as they please and that you’ll take care of the rest (through automatic bill pay, etc.), Panaccione says. And be sure to let them know that you’re doing this because you love them, not because you’re trying to control them.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Award-winning journalist, speaker, family finance expert, and author of Mom and Dad, We Need to Talk.

Cameron Huddleston wrote the daily "Kip Tips" column for Kiplinger.com. She joined Kiplinger in 2001 after graduating from American University with an MA in economic journalism.

-

Turn a $1 Million Nest Egg Into a Lifetime Income Machine

Turn a $1 Million Nest Egg Into a Lifetime Income MachineThe paychecks may stop, but the income shouldn't. Master the art of the "income machine" to fund your dream retirement.

-

2 Ways to Invest if You're Risk Averse But CDs Don't Cut It

2 Ways to Invest if You're Risk Averse But CDs Don't Cut ItInvestors looking for higher yields might want to consider these hybrid products, which blend the possibility of better returns with less downside risk than traditional investing.

-

A Simple Clue Unlocked a Workplace Safety Crisis

A Simple Clue Unlocked a Workplace Safety CrisisA lot of people with hearing issues resist wearing hearing aids. "Nicole" had a very good reason not to wear hers, but figuring out why took some sleuthing.

-

Seven Things You Should Do Now if You Think Your Identity Was Stolen

Seven Things You Should Do Now if You Think Your Identity Was StolenIf you suspect your identity was stolen, there are several steps you can take to protect yourself, but make sure you take action fast.

-

The 8 Financial Documents You Should Always Shred

The 8 Financial Documents You Should Always ShredIdentity Theft The financial documents piling up at home put you at risk of fraud. Learn the eight types of financial documents you should always shred to protect yourself.

-

How to Guard Against the New Generation of Fraud and Identity Theft

How to Guard Against the New Generation of Fraud and Identity TheftIdentity Theft Fraud and identity theft are getting more sophisticated and harder to spot. Stay ahead of the scammers with our advice.

-

12 Ways to Protect Yourself From Fraud and Scams

12 Ways to Protect Yourself From Fraud and ScamsIdentity Theft Think you can spot the telltale signs of frauds and scams? Follow these 12 tips to stay safe from evolving threats and prevent others from falling victim.

-

Watch Out for These Travel Scams This Summer

Watch Out for These Travel Scams This SummerIdentity Theft These travel scams are easy to fall for and could wreck your summer. Take a moment to read up on the warning signs and simple ways to protect yourself.

-

How to Guard Against Identity Theft in 2025

How to Guard Against Identity Theft in 2025Scammers are getting better at impersonating legitimate businesses.

-

Social Media Scams Cost Consumers $2.7B, Study Shows

Social Media Scams Cost Consumers $2.7B, Study ShowsScams related to online shopping, investment schemes and romance top the FTC's social media list this year.

-

Five Ways to Save on Vacation Rental Properties

Five Ways to Save on Vacation Rental PropertiesTravel Use these strategies to pay less for an apartment, condo or house when you travel.