PODCAST: State Taxes on the Middle Class, with Rocky Mengle

Every year Kiplinger ranks all 50 states for their tax-friendliness. For 2020, Senior Tax Editor Rocky Mengle has put the focus on the middle class. Hosts Sandra Block and David Muhlbaum also discuss the student debt moratorium and estate planning for "black sheep" beneficiaries.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Listen now

Subscribe FREE wherever you listen:

Links and resources mentioned in this episode:

- My Student Loan Relief Is Set to Expire, What Now?

- State-by-State Guide to Taxes on Middle-Class Families

- The 10 Least Tax-Friendly States for Middle-Class Families

- The 10 Most Tax-Friendly States for Middle-Class Families

- Estate Planning for ‘Black Sheep’ Beneficiaries

- Financial Planning Tips for Families From Knight Kiplinger

Transcript

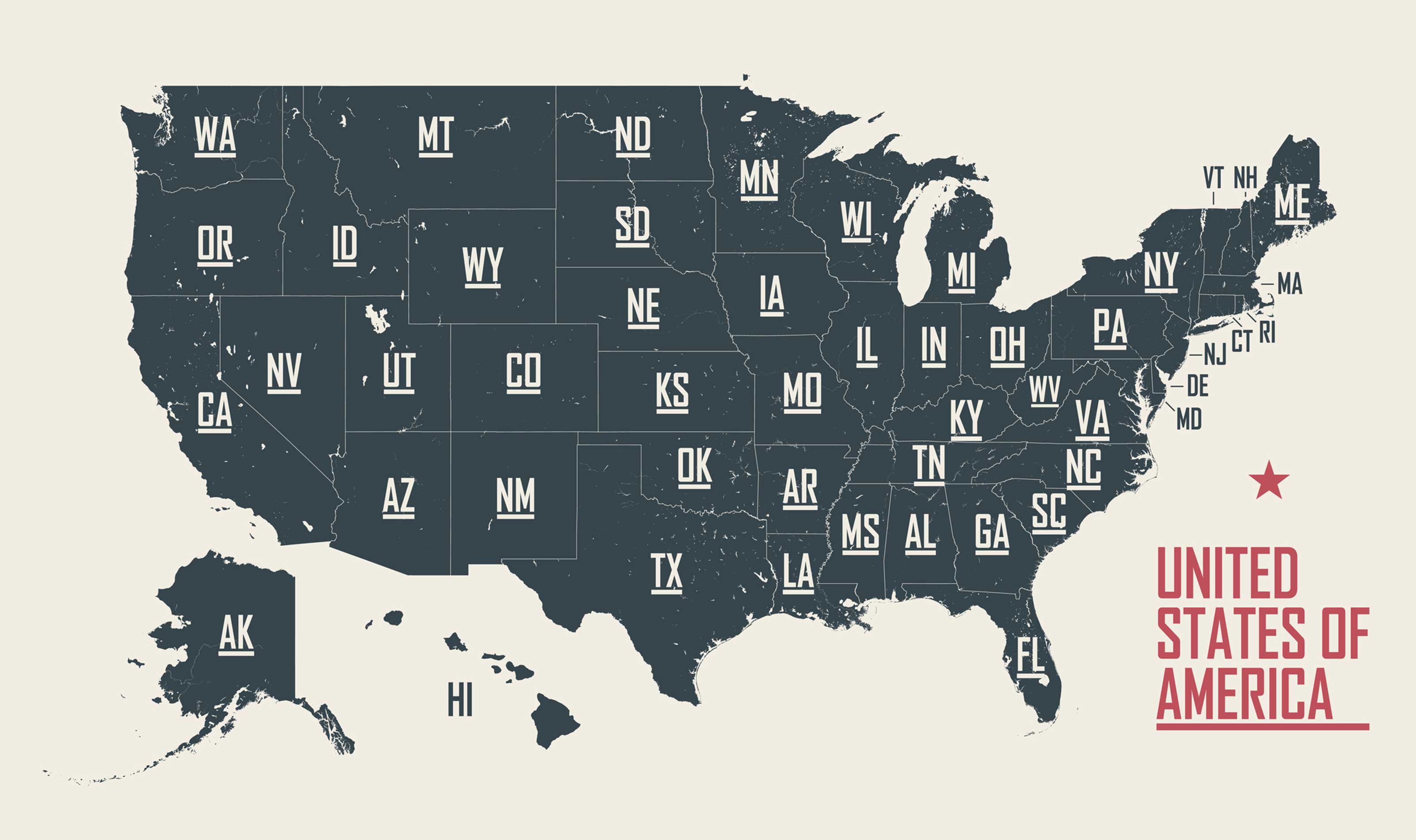

David Muhlbaum: The pandemic-driven embrace of telecommuting has prompted many to take a good, hard look at where they want to live. But when picking a state, taxes really matter. We talked with senior tax editor Rocky Mengle about the latest iteration of Kiplinger's tax map and how it can help people find a money-saving destination. Also in this episode, student loan forbearance and forgiveness, and how black sheep fit in – or don't – when estate planning. That's all coming up on this week's Your Money's Worth. Stick around.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

David Muhlbaum: Welcome to Your Money's Worth. I'm Kiplinger.com senior editor David Muhlbaum, joined by senior editor Sandy Block. Sandy, how are you?

Sandy Block: Doing great today, David.

David Muhlbaum: Good. I know you are eager to talk about student loans this week. They've been in the news of late, specifically, when this debt needs to get repaid and also how much of it needs to get paid.

Sandy Block: More the former than the latter. Less about how much. But we'll get to both.

David Muhlbaum: Okay. So give us the when, then.

Sandy Block: The loan moratorium, which basically means that people who owe student loans don't have to make any payments and interest, does not continue to accrue as long as it's in place. That's been extended until January 31st. This is the second time that ... actually the third time that it's been extended and it's basically due to COVID-19 and the impact on the economy. Now, know that this is only loans that are in the federal student loan program and that's not the only way people finance education. Private loans are a whole nother story, and they're not included in this moratorium.

David Muhlbaum: January 31st. That's when a new administration is going to be in charge. Has Biden said what he plans to do then?

Sandy Block: Well, there's a couple of things. Biden has said that his emergency action plan to save the economy calls for forgiving a minimum of $10,000 in federal student loans. But the prospects for that proposal will depend on the outcome of the Georgia Senate runoff, which will determine which party controls the Senate. Now, Biden could and probably will extend the moratorium for a few more months.

David Muhlbaum: He can just do that on his own.

Sandy Block: He could just do that. Yeah.

David Muhlbaum: While not having to repay I'm sure beats having to repay, this watching and waiting is stressful in its own way. What's your guidance to people who are holding student debt and wondering what the heck is going to happen next?

Sandy Block: You know, let's assume that you're not going to get your loans forgiven any time soon, which means eventually you're going to have to start making payments again. And I've covered student loans for a long time, and what I've frequently seen is that the borrowers with the biggest balances didn't start out that way. They fell behind on payments, went into default, interest in penalties, ballooned the balance, and they ended up going into social security with student debt. One of the unfortunate aspects of student loans is that they're nearly impossible to discharge in bankruptcy. They can literally follow you to your grave. So it's so critical to stay on top of your payments.

Sandy Block: And so if you've had trouble making payments before the moratorium, use this time to talk to your loan servicer about setting up a plan you can afford. There are several programs available through the federal student loan program, ranging from income-based repayment plans to a hardship deferral that you can take advantage of to avoid default. Now, a lot of people get messed up that these programs can be complicated. You have to dot all the I's and cross all of the T's to get it right. Have to provide a lot of paperwork. But you've got time to do that now, so you should.

David Muhlbaum: Do you have any sense that people are?

Sandy Block: That's a good question. I'm worried that they're not, because I think it's like, out of sight, out of mind. I mean, I know how I would respond if somebody said, "No, you just don't have to make any payments." I would go on to do other things. And probably what a lot of people are doing is redirecting that money to other more urgent bills. But again, you got to-

David Muhlbaum: That was kind of the point.

Sandy Block: Yeah, that's the point. But at some point repayments ... and the good thing is, when repayments resume, it's not like you're going to have this huge balance you have to worry about. It's not going to have changed, but it's still going to be out there. You are still going to have to make payments.

David Muhlbaum: Right. Possibly with a discount, but we'll see about that.

Sandy Block: Possibly. We'll see.

David Muhlbaum: Possibly. All right. Thanks, Sandy. Coming up on our next main segment, we talked to senior tax editor, Rocky Mengle about this year's version of the Kiplinger state tax map. For starters, it has a new name.

David Muhlbaum: Welcome back and a warm welcome back to Rocky Mengle, our senior tax editor, who's fresh off the relaunch of the Kiplinger state tax map. It even has a new name, which we'll get into. Welcome back, Rocky. Thanks for joining us. So the Kiplinger tax maps have always been a useful resource and I think this year even more so. One reason is the work you've done in updating the metrics and the focus. And another reason is the COVID-19 pandemic. You know, millions of people have realized they can do their job from anywhere.

David Muhlbaum: And for some people, that means they can live anywhere too, and I think we're seeing that liven up a whole bunch of real estate markets, particularly in resort and rural areas. But those people who are pulling up stakes, they need to think about the tax consequences of where they're going, especially if they're crossing state lines. And that's where our map comes in. Now, full disclosure, both Sandy and I have worked on the tax maps a lot over the years.

Sandy Block: Oh, yeah.

David Muhlbaum: So, maybe we're a bit close to these things. So Rocky, for the purposes of people listening rather than looking, give us an explanation of what the State-by-State Guide to Taxes on Middle-Class Families is.

Rocky Mengle: It's a starting place for someone who wants to evaluate different tax situations in one state versus another. Not only do we have a feature that can actually do a side-by-side comparison of up to five states, we have a long list of state tax facts and information for each state. And you can just go in, click on any state you want, and find out about their income taxes and property taxes, sales taxes, gas taxes, estate taxes, all kinds of information in there. So like you said, if someone's planning on moving from one state to another, this is a good place to start collecting some information about what kind of taxes you might see in one state versus another, or if you're just curious about how your own state kind of measures up.

Sandy Block: It's kind of a fun angle to this as well, because everybody likes rankings, even if you're not a tax geek. So that leaves the question, we tell you which states are the most and least tax friendly. The least tax-friendly is probably the most entertaining as long as you don't live in one, in which case it's kind of infuriating. So what are some of the least tax friendly states? Like, which ones really take a bite and why?

Rocky Mengle: Just a couple on our list of the 10 least tax-friendly states, the worst states: Illinois, Connecticut, New Jersey, New York. Those were probably no surprises. Maryland, Iowa, Hawaii. Well, it's a mixture, because what we're looking at is mainly three types of taxes: income taxes, sales taxes, and property taxes. We have a hypothetical middle class family. When you figure out what their estimated tax obligation would be for all three of those taxes in each state, some of these states might have low income taxes, but very high property taxes and very high sales taxes. So it's kind of a mixture there. The states that are the worst, they kind of have high taxes all across the board. Illinois falls into that category.

David Muhlbaum: You said middle-class right there, and that's a new addition to the title, new for this year. In America, everyone thinks they're middle-class. So, tell me a little bit more about your definition, like, some of the metrics.

Rocky Mengle: Like I mentioned, we have a hypothetical middle-class family. Just to give you some of the details, they have $80,000 in overall income. Most of that, the vast majority of that, $77,000, is from wages, just a regular salary. A little bit of taxable interest, some dividend income, some long-term capital gain income, a little bit of that. And we also gave them a home worth $300,000, and so that way we could kind of measure the property tax burden across all 50 states by assigning that home value.

David Muhlbaum: You know, the $300,000 home value, I saw a little Twitter feedback on that. Basically the person's argument was, well, that buys you a rather different house in California than Kansas.

Rocky Mengle: Yeah, the cost of living factor. And we come up with a rate that we can apply across the board. So we're really looking at kind of the statewide median property tax rate. And I understand that in California, even within a state, your property tax bill in San Francisco is going to be much higher than it is in Bakersfield, let's say. But probably your house is different, too. My feeling is you had a kind of a set house budget to work with based on your income. And if you're moving from one state to another, then you kind of adjust your housing standards, because you can't just automatically say, "Oh, well, I need $100,000 more in income to pay for this house." So, I know when I moved from Richmond to the D.C. Area, I didn't get a house that was as large or as new, and that just kind of comes with the territory. You kind of expect that.

David Muhlbaum: You know, this actually ties back into what we were talking about at the beginning about pandemic-induced moving: people moving to entirely different states, but keeping their job. One of the things that I've heard, at least anecdotally – the Washington Post wrote about this – is a lot of people going from California to Montana. Now, when they do, they're able to take with them all that high property value that they had from California, and to some extent, spend it in their destination state, which is causing some interesting distortions in real estate markets. But I'm on a tangent.

Sandy Block: Well, but that's a good point. David raises a good point here. So maybe you are thinking about moving, Rocky. What's the best way to use this tool? If you're really thinking about moving, I don't know, maybe not from California to Montana, but from Pennsylvania to Delaware or something like that.

Rocky Mengle: Yeah. Use this tool, again, just to kind of evaluate the tax situation in each state. And now I would say focus on your own personal situation. You know, if your salary is high, you definitely want to check out the income tax situation in the two different states that you're looking at. If you plan on buying a really big house or a lot of land, maybe worry more about the property taxes. Or if you shop a lot, what's the sales tax like in each state? And you can get all that information from our tax map and even, like I said, do a side-by-side comparison with up to five states. So that's where this tool really helps you be able to see what it's like in Delaware, see what it's like in Pennsylvania, and then make up your mind as to whether or not you're better off moving from one state to another.

David Muhlbaum: And I'd just like to point out that even beyond those three core metrics that drive the ranking, there are a lot of other values in there: gas taxes, cigarette taxes, marijuana taxes. So depending on your priorities, you could consider that.

Rocky Mengle: Yeah, that's true. If you drink a lot, you know, check out the beer tax rates. We have them in there.

Sandy Block: So, Rocky, let's go to the good news. Can you tell us about some of the most tax-friendly states and why they're there, and maybe one that would surprise people? I'm thinking of a really big state with a whole lot of coastline, and it's not Florida.

Rocky Mengle: Okay. Some of the most tax-friendly states. Wyoming is actually the number one state, the most tax-friendly. There are other ones on there that you're probably not surprised about: Nevada, Florida, Tennessee. These are states with no income tax and that's kind of the driving force here for our middle-class families. Six of the top 10 states are no income state tax states. The surprising one that you were alluding to is California.

Sandy Block: Right.

Rocky Mengle: And everybody knows California has a reputation of being a high-tax state, and it is if you're a millionaire. But we're talking about middle-class families here. Everybody seems to focus on the top income tax rate, which is 13.3%. But again, that's for people making a million dollars or more. For our middle-class family, the hypothetical family that we talked about before, their top income tax rate was only 6%. And we also have to remember that California has a very progressive tax rate system. They're actually ... I guess it's 11 tax brackets, I think ranging from 1% to 13.3. And again, our are middle-class family at 6% came in at ... I guess that's the fourth-lowest rate.

Rocky Mengle: And also remember that these are a graduated income tax rate, which basically means that you're not paying 6% on your entire taxable income amount. For instance, the first $17,000 in California is only taxed at 1% net. That's about 25% of our hypothetical taxpayer's taxable income. So 25% of their income is taxed at only 1%. So that helps a lot, too.

David Muhlbaum: There are states that tax their highest rate at that income level.

Rocky Mengle: Yeah, yeah, exactly. And then in some of those other states, or if you have a flat tax, all your income, or most of it, anyways, is being taxed at that higher rate. California, it's really not the case. You really build up kind of slowly up to the higher tax rates. And that helps.

David Muhlbaum: You know, another factor for some of those low tax states is there's sort of a tax looming over, or a tax that none of the people we're talking about here have to pay, but that affects the tax situation anyway. And that is the severance taxes that those states can collect on their significant mineral wealth: Nevada, Wyoming, Alaska. They come up with a lot of state income by taxing the resource extraction. Therefore, they don't have to take it from the residents by the more conventional means that we're looking at here.

Rocky Mengle: That's true. And the states all have their different ways of collecting the revenue that they need. And like you said, some states rely heavily on severance taxes or other states might tax corporations more so than other states. And if they do that, then that allows them to lower the burden on residents. So, yeah, there's a lot of factors.

David Muhlbaum: Right. Or Delaware. Delaware, there's that odd-

Sandy Block: Corporate tax. Yeah. Yeah.

David Muhlbaum: Or they don't. That's why all the corporations incorporate there. But anyway, one common situation before the pandemic was when someone working in an urban area, where several states come together, they have to pick where to live. Which state? We have that here in the D.C. Area: Virginia, Maryland, Washington, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut. Well, those are all high-tax States. But taxes are often a significant consideration. But some jurisdictions are onto this, right? You get taxed based on where your office or headquarters are located, commuter taxes, that sort of thing.

Rocky Mengle: Yeah. So that's the case in some areas where you have a high concentration of population kind of on a border there. If you cross state lines in order to go to work, depending on where you are, you could be subject to tax not only in your home state where you live, but in the state where you work and that's an extra filing burden. Typically kind of evens out, not always exactly, with tax credits in your home state for whatever income taxes you paid in the state where you work. There are also some reciprocity agreements between states that kind of nullify that possibility of being taxed where you work in addition to where you live.

David Muhlbaum: In the tax map, can a user kind of parse that out?

Rocky Mengle: I mean, yeah, we do indicate where there are local taxes. Yeah. And it gets a little bit more complicated. The tax map won't really flesh that out completely, but it can give you some indications of where that might be an issue.

David Muhlbaum: Telecommuting, on the bigger scale we're seeing now in the pandemic, that could throw a wrench into some of those state tax regimes, right? Where they're trying to collect from commuters?

Rocky Mengle: Absolutely. Yeah. That's a big issue. And a lot of states are wrestling with that right now and still trying to figure out how they want to handle that. There's even lawsuits between states. New Hampshire is suing Massachusetts because Massachusetts is trying to tax people who are living in New Hampshire used to work in Massachusetts, but aren't anymore. So they're not setting foot in Massachusetts, but Massachusetts still wants to tax them. So ...

Sandy Block: Yeah. They're trying to tax people who are working from home, living in a state, but their office is located somewhere else. I just want to throw in that this is something we've been looking into and we will be writing about because, if nothing else, when people file their tax returns this year, a lot of them are going to have to file in multiple states because they lived in more than one state this year. And some people may end up with a surprise tax bill because of these discussions and debates about nexus and where you live and where you pay.

David Muhlbaum: Yeesh.

Sandy Block: Yeah, yeesh is right. It's a mess.

Rocky Mengle: And States are still trying to figure this out.

David Muhlbaum: Well, thank you, Rocky. And I want to note that we're going to have you back on later this month to talk about the other big tax map, Kiplinger's Retiree Tax Map. This is actually our older property. We've been putting this thing together for about 10 years now. So what's in store for this year?

Rocky Mengle: Well, one new twist is that we're using two hypothetical retired couples instead of just one to kind of hammer out our rankings. And the reason to do that is because, unlike the middle-class tax map, that's really kind of focused on someone in a certain income tax or income range, whereas retirees can have any kind of level of income. And so by having multiple hypothetical taxpayers, we can kind of balance that out a little bit. Just kind of a little bit of teaser, you know how we talked about how income taxes were kind of the driving force with middle-class families? Not so much with retirees.

Sandy Block: No, it's what's taxed, and that can be a very big ... You get some real interesting ... It'll be fun to talk about, because you ...Well, fun for us tax geeks, but you get some real big variations in the tax map and the retiree tax map, because some states that might have a fairly high tax rate don't tax most retirement income. So you get kind of a different view of things, I think. It's real interesting.

David Muhlbaum: It's an entirely different set. Well, we'll do that in a couple of weeks. Thank you again, Rocky.

Rocky Mengle: Sounds good. Thanks, bye.

David Muhlbaum: All right, Sandy, what's a black sheep? Not a black swan, a black sheep. Your definition, please.

Sandy Block: Isn't it the troublemaker, the one who doesn't fit in, does things differently? The connotation is not particularly good, I think.

David Muhlbaum: Yeah. Thanks. That's the answer I was looking for. Although I would note that, as I did a bit of research on this, it turns out that the black sheep from the children's story is actually the good guy. Those three bags of wool, baa baa black sheep, third is for the little boy who lives down the lane and the little boy really needs clothes. There's a long version of this.

Sandy Block: Okay. I missed out on the fairytales. I went right to the grownup books.

David Muhlbaum: Right. Portnoy's Complaint? Forever?

Sandy Block: I think it was the complete works of Judith Krantz. I was advanced.

David Muhlbaum: Ooh.

Sandy Block: Okay. Just stop. Black sheep, David.

David Muhlbaum: Okay. I had black sheep on the brain because of an article we featured on kiplinger.com with the catchy title "Estate Planning for Black Sheep Beneficiaries." It's also got a smashing picture of a sheep, too. But what it's about is how to give an inheritance to someone who might not be fully deserving of it or ready to handle it.

Sandy Block: So the person who might get cut out of your will.

David Muhlbaum: Yeah. Who might, yeah. Well, what struck me among the nuts and bolts of the piece was how people are just often really reluctant to do that. That sort of scene you see in a movie where there's a dramatic reading of the will and someone gets nothing, it just sort of seems it's more literary than real life.

Sandy Block: Well, yeah, and it is. But the question of how to split up the money, equal parts or not, that's a big one. We actually discussed that with Knight Kiplinger a couple of years ago, just around this time, when people have family money, this whole issue of not just disinheriting somebody, but maybe one of your children is a hedge fund manager and the other is a school teacher, or one of your children is disabled, or maybe one of your children has an addiction of some kind, how do you allocate the money in that kind of situation?

David Muhlbaum: Yeah, the article, it gets into that as well. And it also reassures people that if disinheritance really is the way to go, well, you can do it, but there's nuance available, and the main vehicle that provides nuance is a trust.

Sandy Block: So with a trust, you're basically assigning the hard work to someone else and protecting your assets, not only against somebody that maybe you want to disinherit, but I think it can also protect you from going into court, from court challenges. It can perform a lot of tasks.

David Muhlbaum: Yeah. And usually with a trust, you have to designate an executor, right? And people usually turn to a family friend for the responsibilities of that. But for the sort of black sheep scenario where you have someone who, because of mental illness or substance abuse, they might have sort of long-term issues going on, that could be a burden for that executor. So again, from the article, you can also name a professional trustee, like that's a job, a professional trustee to take care of the administrative responsibilities of the trust. That costs money. Nothing is free. But I think when people are trying to think, how am I going to exert some influence for the good beyond the grave without imposing too much of a burden on the other members of the family while still taking care of, as you wish, the black sheep, that's one way of resolving these problems,

Sandy Block: Right. And it could be money ... It does cost money, but it could be money well spent. And obviously, we'll link this in the show notes. But the other thing I remember Knight saying, whether you go the trust route, or you just decide that you're going to give different amounts to different children, put it in writing. Explain, maybe you don't want to explain ahead of time because you got a real-

David Muhlbaum: No, that'll be a conversation. Right.

Sandy Block: You got a real black sheep in the family. But maybe write a letter. Explain the reasons that you're doing what you're doing so that it's not necessarily going to prevent family fights, but it makes sure that people understand your intentions and that your intentions are good.

David Muhlbaum: Yeah. Did you see the movie "Knives Out?"

Sandy Block: No, but now I want to. Is that the one about Clue? I don't remember.

David Muhlbaum: It's sort of Clue-influenced, but there's a will and who gets the money and who gets cut out is really kind of at the core of the plot, and I thought of this when I was reading about the black sheep, but it turns out there's more than one black sheep and well ... there ... anyway.

Sandy Block: It's a herd of black sheep.

David Muhlbaum: There's a whole herd of black sheep. We'll put a link to that article, nice article, and possibly also the nursery tale in our show notes. Thanks so much, Sandy.

Sandy Block: Bye.

David Muhlbaum: And that will just about do it for this episode of Your Money's Worth. I hope you enjoyed it and I hope you'll sign up for more at Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your content. When you do, please give us a rating and a review. If you're already a subscriber and haven't yet put in a good word for us, well, please do. To see the links we've mentioned on our show, along with more great Kiplinger content on the topics we discussed on today's show, visit kiplinger.com/podcast. There are transcripts there as well. And if you're still here, because you want to give us a piece of your mind, you can stay connected with us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or by emailing us at podcast@kiplinger.com. Thanks for listening.

Subscribe FREE wherever you listen:

Links and resources mentioned in this episode:

- My Student Loan Relief Is Set to Expire, What Now?

- State-by-State Guide to Taxes on Middle-Class Families

- The 10 Least Tax-Friendly States for Middle-Class Families

- The 10 Most Tax-Friendly States for Middle-Class Families

- Estate Planning for ‘Black Sheep’ Beneficiaries

- Financial Planning Tips for Families From Knight Kiplinger

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

In his former role as Senior Online Editor, David edited and wrote a wide range of content for Kiplinger.com. With more than 20 years of experience with Kiplinger, David worked on numerous Kiplinger publications, including The Kiplinger Letter and Kiplinger’s Personal Finance magazine. He co-hosted Your Money's Worth, Kiplinger's podcast and helped develop the Economic Forecasts feature.

-

Dow Absorbs Disruptions, Adds 370 Points: Stock Market Today

Dow Absorbs Disruptions, Adds 370 Points: Stock Market TodayInvestors, traders and speculators will hear from President Donald Trump tonight, and then they'll listen to Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang tomorrow.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Maximize Your Social Security Check?

Quiz: Do You Know How to Maximize Your Social Security Check?Quiz Test your knowledge of Social Security delayed retirement credits with our quick quiz.

-

Will You Get a Trump Tariff Refund in 2026? What to Know Now

Will You Get a Trump Tariff Refund in 2026? What to Know NowTax Law The Supreme Court's tariff ruling has many wondering about refund rights and how tariff refunds would work.

-

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K Senior Tax Deduction Means for Medicare IRMAA

Over 65? Here's What the New $6K Senior Tax Deduction Means for Medicare IRMAATax Breaks A new tax deduction for people over age 65 has some thinking about Medicare premiums and MAGI strategy.

-

In Arkansas and Illinois, Groceries Just Got Cheaper, But Not By Much

In Arkansas and Illinois, Groceries Just Got Cheaper, But Not By MuchFood Prices Arkansas and Illinois are the most recent states to repeal sales tax on groceries. Will it really help shoppers with their food bills?

-

New Bill Would Eliminate Taxes on Restored Social Security Benefits

New Bill Would Eliminate Taxes on Restored Social Security BenefitsSocial Security Taxes on Social Security benefits are stirring debate again, as recent changes could affect how some retirees file their returns this tax season.

-

Can I Deduct My Pet On My Taxes?

Can I Deduct My Pet On My Taxes?Tax Deductions Your cat isn't a dependent, but your guard dog might be a business expense. Here are the IRS rules for pet-related tax deductions in 2026.

-

Tax Season 2026 Is Here: 8 Big Changes to Know Before You File

Tax Season 2026 Is Here: 8 Big Changes to Know Before You FileTax Season Due to several major tax rule changes, your 2025 return might feel unfamiliar even if your income looks the same.

-

2026 State Tax Changes to Know Now: Is Your Tax Rate Lower?

2026 State Tax Changes to Know Now: Is Your Tax Rate Lower?Tax Changes As a new year begins, taxpayers across the country are navigating a new round of state tax changes.

-

3 Major Changes to the 2026 Charitable Deduction

3 Major Changes to the 2026 Charitable DeductionTax Breaks About 144 million Americans might qualify for the 2026 universal charity deduction, while high earners face new IRS limits. Here's what to know.

-

Retirees in These 7 States Could Pay Less Property Taxes Next Year

Retirees in These 7 States Could Pay Less Property Taxes Next YearState Taxes Retirement property tax bills could be up to 65% cheaper for some older adults in 2026. Do you qualify?