How to Tell Your Own Story

Your life told well could be the best gift you can leave.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Most of us worry about preserving our assets. We tweak investment portfolios to reduce risks. We make arrangements for what will happen to our money and real estate after we die.

There is one vulnerable asset we tend to overlook: Our stories. There is more long-term value than you may think in your experiences and reflections about what you have tried to do with your life, why and how it has all panned out.

To the extent that we will be remembered at all, it is because people know at least a few of our stories: the strangest, worst and most wonderful things that have happened to us; how we met our spouse or partner, why we got involved in one rat race or another, our ways of coping with hard times, our biggest triumphs and dumbest errors, and what we learned from them.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

If you have told some of those stories, think back: Were your children or chums taking notes? Probably not. At best, they will recall only vague scraps of whatever you shared. Vague stories are fast-depreciating assets.

I write obituaries for The Wall Street Journal and other newspapers. As part of my research, I frequently talk with the adult children of people who have recently died. What strikes me over and over is how much they want their parents' stories to be remembered — and how little they know about their parents' lives.

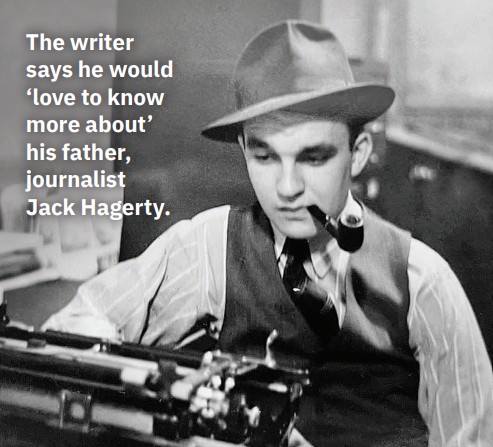

And I know this myself: Twenty-eight years after my dad died, I would love to know more about his life and what he thought about it — things we never got around to discussing. What exactly did his father do for a living? And why did my shy dad, who typed with just two of his fingers, decide to become a journalist? Did he just like the hat?

Your story may be the best gift you ever give to your friends and family. It's a gift only you can give. If you don't give it, it vanishes when you die.

So how can you preserve that story?

Interview yourself

Start by asking yourself a few questions: What would I like people to remember about me? What have I learned that might be interesting and perhaps useful to others? What are the most surprising things that have happened to me? Then start making notes.

The long and short

Let's call this project your life story, whether you come up with 500 words or 500 pages. Whatever you write about your life may provide material for your obituary (see below) but you should consider going well beyond the space limits of obits to share more personal stories with friends, family and anyone else who may care, now or in the distant future.

There’s danger in delaying

The important thing is to get started. Why not today? Don't wait until you are on your deathbed; you may not be in the mood.

Trust your voice

Don't worry if you don't have a compelling theme or message for the world. Few of us do. And don't fuss about literary style. Your natural voice is the best bet.

You don't have to start at the beginning

Many people don't know where to start. My advice is to start anywhere. You don't need a brilliant opening line. Just start writing about whatever strikes you as most interesting, amusing or important. Writing about one episode will remind you of others. Let your story find its own shape and meaning. You can always tidy up or rearrange later.

Some people go with chronological order, providing a simple roadmap. Others group memories by themes. Or you can simply stack up a series of anecdotes and perhaps append a life lesson to each one.

It's not all about you

Throw in family history and memories of special friends.

Include both the good and the bad

Your story should not read like a nomination for sainthood. But don't feel bound to confess all of your sins. That would get tedious. Leave out anything that would hurt other people. Take your share of the blame for any disasters, and let the rest go. If you want to be remembered as a class act, don't use your story to settle scores.

You're likely to leave some things out because they're just too embarrassing. That's okay.

Your readers need a little help

Remember that you are writing not just for people who know you now but quite possibly for future generations. If you mention going to the lake to visit Fred, your immediate family may know which lake that was and who Fred was. Your great-grandchildren will need far more information.

You may know what it was like to live in a pre-internet world with rotary phones and only a few TV channels. Your grandchildren don't — and one day they may want to understand more about the past.

Hire a ghost or record yourself

If you hate to write, you can hire someone to interview you and write your story. That could cost hundreds or thousands of dollars, depending on the writer you choose and how long and complicated your story is.

Or you can record yourself talking. But if you do that, make a transcript. The recording medium you're using may not exist 20 years from now. Paper probably will. Save digital copies as well.

Read your transcript carefully; make corrections or additions to ensure it's accurate and comprehensible. Have someone else read it and tell you what makes sense, what doesn't, what's missing, what's interesting and what's not.

Don't let your story get lost in the attic

You can have your story bound at a local print shop. Or you can go online and find firms that will turn it into a book worthy of someone's shelf or coffee table. In either case, use photos (with detailed captions) to make your story more approachable.

There's always that nagging thought: I'm not famous. Who will care about my story? Well, you never know. Anne Frank and Samuel Pepys weren't famous. We're still reading what they wrote. If even one of my two children finds value in my story, I've succeeded.

And if my dad had asked, "Who will care?" I could have told him: "I will care."

Writing your obituary

While you're preserving your life story, do your family and friends a favor: Write down a short version, 800 words or fewer, that can serve as an obituary when you die.

After your death, your story almost certainly will be told in some fashion. If not by you, then by a family member or funeral director, in haste. So the question is only whether your story will be told well or badly.

The best obituaries are condensed summaries of your life story. They give the big picture of what you did and convey a sense of your priorities and personality. They should not be occasions for clichés, pieties or statements of the obvious. There is no need to say you loved your spouse, family and dog — unless you think people will doubt that.

What to include

- Your full name, including your middle name, even if you hated it. That helps differentiate you from people with similar names.

- Date of birth, where you were born, where you grew up. (You can leave your birth date out of publicly distributed obits, but keep the information in the family version so future family historians can learn more about you.)

- What your parents did for a living. Be specific. Not "my dad worked at XYZ Corp." Exactly what he did there. Owned it? Ran it? Swept the floors?

- The early experiences that helped shape your future.

- Why and how you got on a career path and decided to get married or stay single. Don't just tell us what you did. Tell us why and how.

- Your achievements. But, please, not all of them! Leave out the minor stuff.

- Suggestions for memorial gifts.

- Try to include a little humor, without turning the entire exercise into a joke. At funerals, the best eulogies include a mention of some peculiar habit or trait that makes us laugh in spite of our grief. Our laughter reassures us that we can still feel joy — and that our loved one lives on in our memories.

Remember my motto: If obituaries can't be fun, what's the point of dying?

Note: This item first appeared in Kiplinger Retirement Report, our popular monthly periodical that covers key concerns of affluent older Americans who are retired or preparing for retirement. Subscribe for retirement advice that’s right on the money.

Related content

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

James R. Hagerty writes obituaries for the Wall Street Journal. He is the author of Yours Truly, a guide to writing life stories. He can be reached by email at jamesrhagerty888@gmail.com or LinkedIn.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

AI Sparks Existential Crisis for Software Stocks

AI Sparks Existential Crisis for Software StocksThe Kiplinger Letter Fears that SaaS subscription software could be rendered obsolete by artificial intelligence make investors jittery.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the 'Medigap Trap?'

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the 'Medigap Trap?'Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

We Retired at 62 With $6.1 Million. My Wife Wants to Make Large Donations, but I Want to Travel and Buy a Lake House.

We Retired at 62 With $6.1 Million. My Wife Wants to Make Large Donations, but I Want to Travel and Buy a Lake House.We are 62 and finally retired after decades of hard work. I see the lakehouse as an investment in our happiness.

-

Social Security Break-Even Math Is Helpful, But Don't Let It Dictate When You'll File

Social Security Break-Even Math Is Helpful, But Don't Let It Dictate When You'll FileYour Social Security break-even age tells you how long you'd need to live for delaying to pay off, but shouldn't be the sole basis for deciding when to claim.

-

I'm a Wealth Adviser Obsessed With Mahjong: Here Are 8 Ways It Can Teach Us How to Manage Our Money

I'm a Wealth Adviser Obsessed With Mahjong: Here Are 8 Ways It Can Teach Us How to Manage Our MoneyThis increasingly popular Chinese game can teach us not only how to help manage our money but also how important it is to connect with other people.

-

Global Uncertainty Has Investors Running Scared: This Is How Advisers Can Reassure Them

Global Uncertainty Has Investors Running Scared: This Is How Advisers Can Reassure ThemHow can advisers reassure clients nervous about their plans in an increasingly complex and rapidly changing world? This conversational framework provides the key.

-

5 Ronald Reagan Quotes Retirees Should Live By

5 Ronald Reagan Quotes Retirees Should Live ByThe Nation's 40th President's wit and wisdom can help retirees navigate their financial and personal journey with confidence.

-

We're 78 and Want to Use Our 2026 RMD to Treat Our Kids and Grandkids to a Vacation. How Should We Approach This?

We're 78 and Want to Use Our 2026 RMD to Treat Our Kids and Grandkids to a Vacation. How Should We Approach This?An extended family vacation can be a fun and bonding experience if planned well. Here are tips from travel experts.

-

Should You Jump on the Roth Conversion Bandwagon? A Financial Adviser Weighs In

Should You Jump on the Roth Conversion Bandwagon? A Financial Adviser Weighs InRoth conversions are all the rage, but what works well for one household can cause financial strain for another. This is what you should consider before moving ahead.