6 Wall Street Stocks That Are Cheap: Goldman Sachs, More

As candidates and others poor-mouth the financial industry, you can score stock bargains in the sector.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Wall Street, the alleged culprit of the financial meltdown that started eight years ago, has become the whipping boy for the 2016 presidential race. Does the intense animosity of Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump explain the dive in the share prices of investment banks, private-equity firms and managers of hedge funds?

It’s hard to escape the correlation. On May 26, 2015, Sanders, the socialist senator from Vermont, announced that he would seek the Democratic presidential nomination. Three weeks later, Trump, the wealthy New York businessman, announced his quest for the Republican nod. A week after that, shares of Goldman Sachs Group (symbol GS, $155), the very symbol of Wall Street power and wealth, peaked at $219 a share. Within eight months, Goldman shares had fallen by nearly one-third. Morgan Stanley (MS) dropped even more. (All prices and returns are as of March 1; investments in boldface are those I recommend.)

Sanders has made reforming Wall Street the focus of his campaign. Clinton, despite large contributions from the financial sector, has echoed Sanders. The surprise is that attacks by Republicans have been nearly as strident. Trump said of hedge funds: “They’re paying nothing [in taxes]. And it’s ridiculous ... the hedge fund guys didn’t build this country. These are guys that shift paper around and they get lucky.”

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

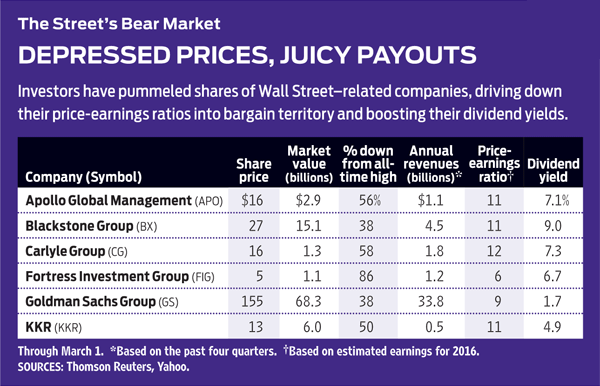

Clinton, like Sanders and Trump, wants to end the “carried interest” loophole, which taxes what many consider a private-equity firm’s incentive income at the capital-gains rate rather than the much steeper ordinary income tax rate. Like the investment-banking stocks, shares of private-equity firms have tanked. Blackstone Group (BX) has sunk 39% since May 2015; Carlyle Group (CG) has fallen by half and traded at an all-time low in February; KKR (KKR) has slid from $24 in June to $13.

Antagonistic candidates, however, aren’t the only problem. Private-equity firms—whose traditional business is buying companies, then trying to improve their performance and selling them at a profit—are having a tough time finding bargains, which are their lifeblood. Prospective acquisitions have been picked over, and the days of easy money are over. The gems, such as Beats, the headphone maker, are getting scarcer as intense competition among the firms doing the buying pushes up purchase costs. Apple purchased Beats from Carlyle in 2014, allowing Carlyle to pocket an 80% profit in less than a year.

Sagging profits. As a result, the prices of some private-equity stocks started to fall well before the presidential candidates began giving the firms heat. Apollo Global Management (APO), founded in 1990, peaked in January 2014 at $36 and now trades at $16, a decline that makes perfect sense given that earnings per share skidded from $4.80 in 2013 to just 96 cents last year. Earnings at Blackstone, whose holdings include fashion designer Versace and camera maker Leica, dropped by nearly half in 2015 compared with a year earlier. KKR, the firm that pulled off the $24 billion RJR Nabisco deal in 1988, at the time the biggest buyout in history, hasn’t come close to matching the earnings per unit it generated in 2010, the year it went public (publicly traded private-equity firms are set up as limited partnerships).

The firms are moving further afield, into loans to businesses, a territory dominated by commercial banks, and investments in distressed assets abroad, generally the province of hedge funds. Meanwhile, lenders to the private-equity firms are getting skittish themselves, especially after big losses in energy as oil prices have collapsed.

As troubles have mounted, share prices have come down, as have price-earnings ratios. Based on the average of analyst profit forecasts for 2016, Apollo, Blackstone and Carlyle all trade at P/Es of 11 to 12 (the overall stock market’s P/E is 16). It’s hard to resist private-equity stocks at these prices. And although the dividends these firms pay bounce up and down as they sell their holdings from year to year, the current yields look mouthwatering: Blackstone’s is 9.0%; Carlyle’s, 7.3%; Apollo’s, 7.1%.

[page break]

The tax advantage of carried interest will almost certainly disappear under the next president, but that prospect is already baked into stock prices, as are increased competition and harder-to-find deals. Still, analysts believe all of these firms will report sharply higher earnings next year.

Hedge funds and investment banks are also closely identified with Wall Street. Hedge funds raise money mainly from pension funds, university endowments, sovereign wealth funds (created by rich countries such as Kuwait and Norway) and well-heeled individuals, then invest in a wide variety of assets, from foreign currencies to small-cap stocks. Nearly all of the largest hedge funds, such as Bridgewater, Pershing Square and Caxton, are privately held partnerships, though some big ones are divisions of commercial banks and asset management companies, such as JPMorgan Chase (JPM) and BlackRock (BLK). One of the few hedge funds whose shares are traded on the New York Stock Exchange is Fortress Investment Group (FIG). Fortress has suffered a number of setbacks, and its stock has plunged 84% since hitting a record-high price in early 2007. The stock, which yields 6.7%, is risky but worth a look.

Investment banks focus on raising capital for corporations and governments through such activities as bringing companies public, advising on mergers and underwriting bond issues. The repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999 tore down the barriers between commercial and investment banking. In investment-banking activities, commonly thought of as the province of Wall Street, Goldman is the standout—and a prime target of critics. Its ties to government are cozy and controversial. Two of the past seven Treasury secretaries, Robert Rubin and Henry Paulson, were top Goldman executives.

Goldman’s shares, trading at a P/E of 9 based on profit estimates for 2016, appear supercheap. The stock price is lower today than it was 10 years ago—and so are revenues and earnings. The Dodd-Frank law and other regulatory constraints that followed the Great Recession have clearly harmed profits, and so has weakness in the market for initial public offerings and high-yield bonds. The merger business, strong for much of 2015, has also been slipping. In truth, the anemic pace of economic growth is hurting Goldman more than the assaults of Sanders, Clinton and Trump.

When politicians talk about “Wall Street,” they often include money-center banks with huge consumer bases, such as Bank of America (BAC), Citigroup (C) and JPMorgan Chase. Although their stock prices are also down since last summer, I find them less attractive than private-equity firms and near-pure investment banks such as Goldman, which tend to be more efficient and are magnets for top talent. The latter are magnets for political attacks as well, but they have also shown that they can navigate around obstacles that governments put in their paths.

No matter the rhetoric, whoever becomes president will have a hard time throttling back firms that raise capital and deploy it. Now appears to be a good time to take advantage of negative perceptions that have driven their share prices into fertile territory.

James K. Glassman, a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, is the author, most recently, of Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments in a Time of Turbulence. He owns none of the stocks mentioned.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

The Cost of Leaving Your Money in a Low-Rate Account

The Cost of Leaving Your Money in a Low-Rate AccountWhy parking your cash in low-yield accounts could be costing you, and smarter alternatives that preserve liquidity while boosting returns.

-

I want to sell our beach house to retire now, but my wife wants to keep it.

I want to sell our beach house to retire now, but my wife wants to keep it.I want to sell the $610K vacation home and retire now, but my wife envisions a beach retirement in 8 years. We asked financial advisers to weigh in.

-

How to Add a Pet Trust to Your Estate Plan

How to Add a Pet Trust to Your Estate PlanAdding a pet trust to your estate plan can ensure your pets are properly looked after when you're no longer able to care for them. This is how to go about it.

-

Nasdaq Leads Ahead of Big Tech Earnings: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads Ahead of Big Tech Earnings: Stock Market TodayPresident Donald Trump is making markets move based on personal and political as well as financial and economic priorities.

-

Small Caps Can Only Lead Stocks So High: Stock Market Today

Small Caps Can Only Lead Stocks So High: Stock Market TodayThe main U.S. equity indexes were down for the week, but small-cap stocks look as healthy as they ever have.

-

Dow Adds 292 Points as Goldman, Nvidia Soar: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 292 Points as Goldman, Nvidia Soar: Stock Market TodayTaiwan Semiconductor's strong earnings sparked a rally in tech stocks on Thursday, while Goldman Sachs' earnings boosted financials.

-

'Donroe Doctrine' Pumps Dow 594 Points: Stock Market Today

'Donroe Doctrine' Pumps Dow 594 Points: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 rallied but failed to turn the "Santa Claus Rally" indicator positive for 2026.

-

Stocks Struggle for Gains to Start 2026: Stock Market Today

Stocks Struggle for Gains to Start 2026: Stock Market TodayIt's not quite the end of the world as we know it, but Warren Buffett is no longer the CEO of Berkshire Hathaway.

-

Dow Rises 585 Points on Rate Cut Hope: Stock Market Today

Dow Rises 585 Points on Rate Cut Hope: Stock Market TodayStocks moved more than 1% again Monday, this time to the upside following the Jobs Friday sell-off.

-

What CEOs Say About President Trump and Fed Chair Powell

What CEOs Say About President Trump and Fed Chair PowellTop opinion-shapers and decision-makers are expressing mixed views on the evolving conflict between the White House and the central bank.

-

Stock Market Today: S&P 500, Nasdaq Hit New Highs on Retail Sales Revival

Stock Market Today: S&P 500, Nasdaq Hit New Highs on Retail Sales RevivalStrong consumer spending and solid earnings for AI chipmaker Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing boosted the broad market.