Federal Debt: A Heavy Load

The debt continues to grow, but record-low interest rates could ease the long-term damage.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

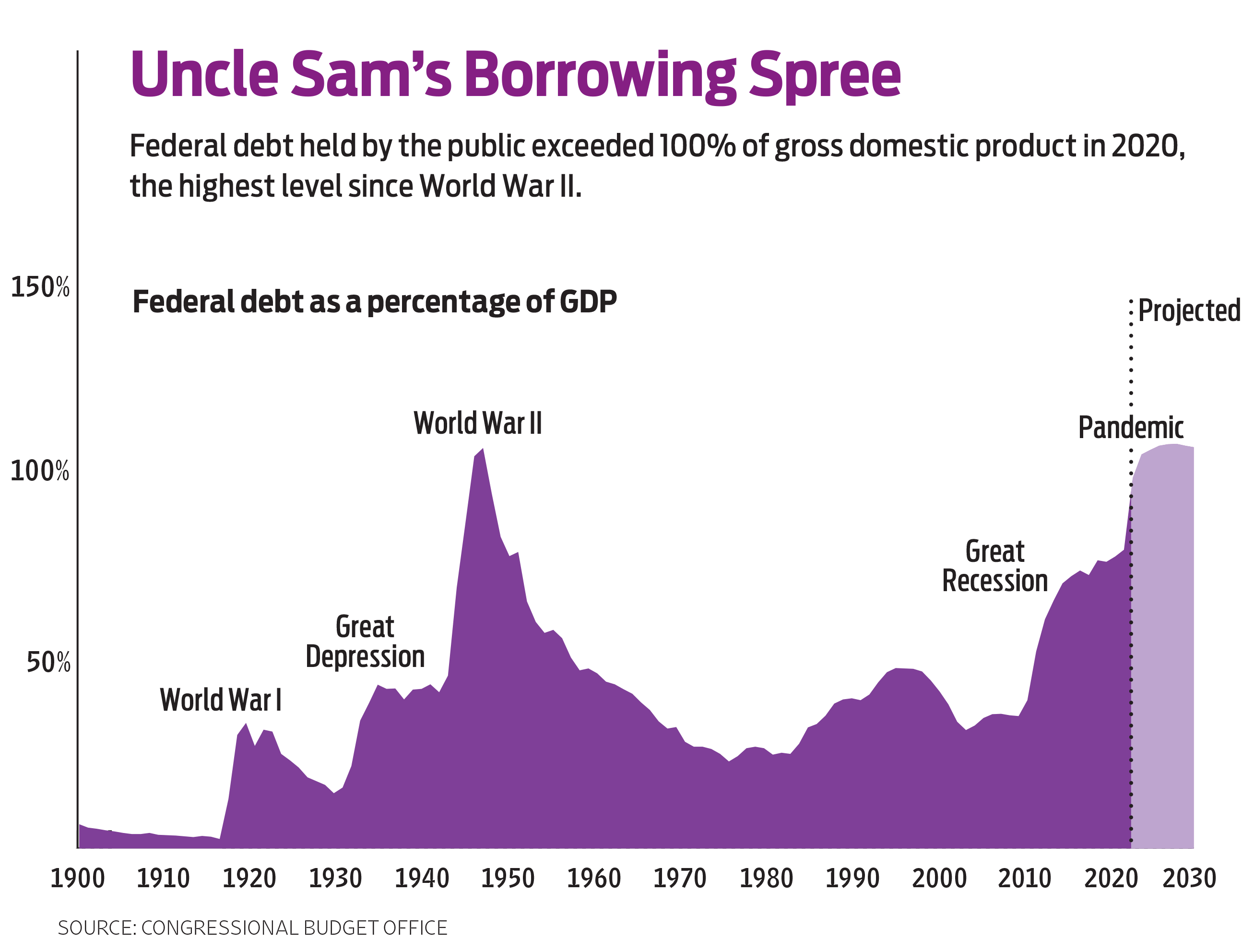

As recently as 2007, the amount of federal government debt—Treasury securities held by the public—was just 35% of gross domestic product. At the end of 2019, it was 79%, and it’s likely to hit 104% in 2021. It only gets worse: The debt will likely rise to 109% by 2030 and approach 200% of GDP by 2050, according to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office. Those estimates don’t include another fiscal stimulus (which was being negotiated at press time) and assume Congress won’t extend tax breaks scheduled to expire in 2025.

For most of us, that kind of balance sheet would be ruinous. Interest rates would eat away at our income, making it difficult to pay expenses. Certainly, that has been the traditional view of the federal government’s debt: As rising deficits increase the amount of interest the government must pay each year, there’s less money available for other things. There have also been concerns about what would happen if China and other foreign investors were to stop buying Treasury securities. A deluge of debt would flood the market, and interest rates would have to rise to entice investors to buy it. That would cause interest rates on consumer and business loans to follow suit, which would hurt the economy.

So, should we worry? Well, yes and no.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Reasons to be fearful. All things being equal, it’s better to have low debt than high debt. Interest rates are very low right now, but they could rise in the future. Economists have generally believed that a country should try to keep debt levels as a percentage of GDP steady over time, increasing debt during economic downturns and paying it down during good times. When the debt piles up year after year, it reduces the government’s ability to stimulate the economy when the next recession comes around. Governments that try to finance their deficits by increasing the money supply (usually by having the central bank buy the government’s debt) risk triggering inflation—and in especially bad cases, hyperinflation. In Germany in the 1920s, shoppers needed a wheelbarrow full of cash to buy a loaf of bread. Scholars believe this led to political instability that fueled the rise of Adolf Hitler.

Reasons to relax. The U.S. has the world’s largest economy and a sound financial system. Central banks around the world hold more dollars than any other currency. Most of the world’s exports and imports are priced in dollars. The world’s investors flock to U.S. Treasury securities because they are the safest in the world, with close to zero risk of default. That allows the U.S. Treasury to continue to sell its bonds despite low interest rates.

The Federal Reserve has signaled that it won’t raise short-term interest rates for the next three years, so we can expect the rates the government pays to stay relatively low for a long time. Low rates keep interest from eating up ever larger portions of the government pie.

In addition, the debt may never have to be fully paid back. As mentioned earlier, the Federal Reserve could buy government debt. Ordinarily, that would cause inflation. But since the early 1990s, something strange has happened: Inflation has been a constant 2% to 3% every year, regardless of whether federal government debt has increased or decreased. After the government increased spending in the wake of the Great Recession, inflation barely budged. A decline in oil prices since 2015 has helped, but there has been no inflationary reaction to debt levels, even when the unemployment rate fell to 3.5% in early 2020.

Conventional wisdom has long held that a country was in trouble if its debt exceeded 100% of GDP. But Japan’s debt has risen to 266% of GDP with no accompanying inflation. The government issues bonds, and the Bank of Japan buys bonds that aren’t purchased by the public. Japan’s example has changed the way economists think of risk for highly developed countries, and many think the U.S. could tolerate a high level of debt as well.

Whichever side you come down on, you can expect the government to run large deficits (relative to GDP) for a while and the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates low for as long as inflation behaves. Although low rates hurt income-seeking savers, they tend to buoy the stock market, which is beneficial for investors who have money in stocks and stock funds. As for how this trend will affect the overall economy, the only certainty is that we’re traveling in uncharted territory.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

David is both staff economist and reporter for The Kiplinger Letter, overseeing Kiplinger forecasts for the U.S. and world economies. Previously, he was senior principal economist in the Center for Forecasting and Modeling at IHS/GlobalInsight, and an economist in the Chief Economist's Office of the U.S. Department of Commerce. David has co-written weekly reports on economic conditions since 1992, and has forecasted GDP and its components since 1995, beating the Blue Chip Indicators forecasts two-thirds of the time. David is a Certified Business Economist as recognized by the National Association for Business Economics. He has two master's degrees and is ABD in economics from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayAnother worrying bout of late-session weakness couldn't take down the main equity indexes on Wednesday.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

Big Change Coming to the Federal Reserve

Big Change Coming to the Federal ReserveThe Lette A new chairman of the Federal Reserve has been named. What will this mean for the economy?

-

The U.S. Economy Will Gain Steam This Year

The U.S. Economy Will Gain Steam This YearThe Kiplinger Letter The Letter editors review the projected pace of the economy for 2026. Bigger tax refunds and resilient consumers will keep the economy humming in 2026.

-

Trump Reshapes Foreign Policy

Trump Reshapes Foreign PolicyThe Kiplinger Letter The President starts the new year by putting allies and adversaries on notice.

-

Congress Set for Busy Winter

Congress Set for Busy WinterThe Kiplinger Letter The Letter editors review the bills Congress will decide on this year. The government funding bill is paramount, but other issues vie for lawmakers’ attention.

-

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026The Kiplinger Letter Here are some of the biggest events and trends in economics, politics and tech that will shape the new year.

-

Special Report: The Future of American Politics

Special Report: The Future of American PoliticsThe Kiplinger Letter Kiplinger assesses the political trends and challenges that will define the next decade.

-

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026The Kiplinger Letter Economic growth across the globe will be highly uneven, with some major economies accelerating while others hit the brakes.

-

Shoppers Hit the Brakes on EV Purchases After Tax Credits Expire

Shoppers Hit the Brakes on EV Purchases After Tax Credits ExpireThe Letter Electric cars are here to stay, but they'll have to compete harder to get shoppers interested without the federal tax credit.