Why Airline Stocks Are a Bad Deal

Seven good reasons to avoid airline stocks

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

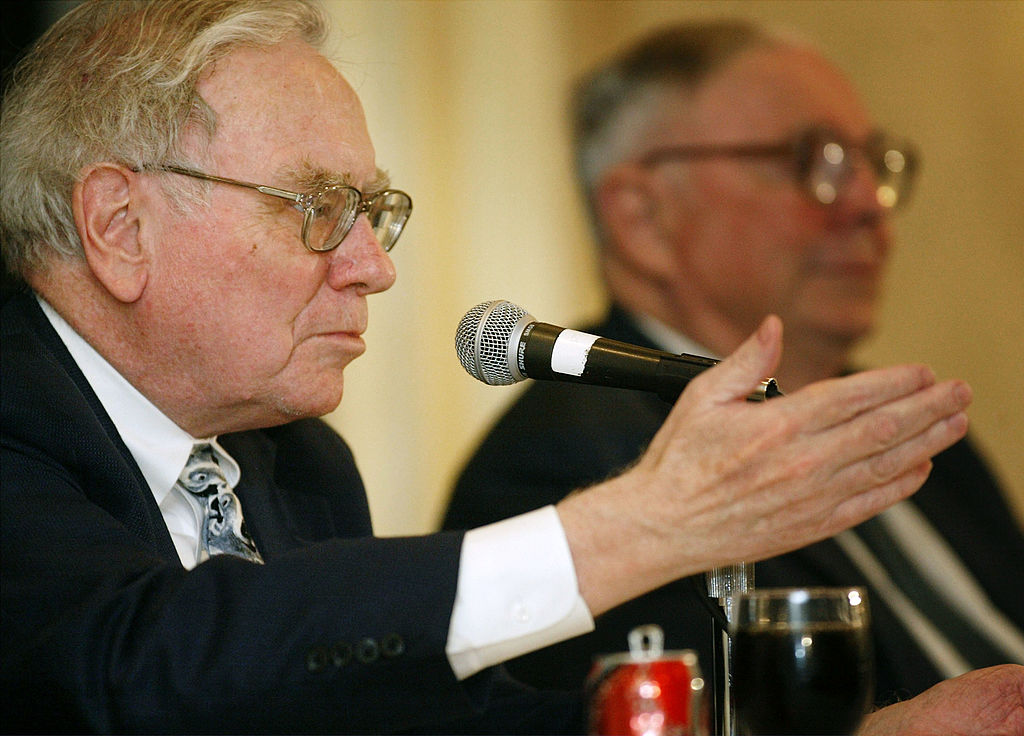

A bit of advice about airline stocks: Resist them. I know it’s hard. Warren Buffett once joked about his own addiction, saying, “I am Warren, and I am an aeroholic.” Buffett’s mentor, the scholar and investor Benjamin Graham, was right from the start. He wrote in 1949 that it’s obvious that the airline industry will take off, but that doesn’t make airline stocks good investments.

In the late 1980s, Buffett bought US Airways preferred shares anyway and made a little money for Berkshire Hathaway on the dividends, all the while disparaging his choice. In 2007, he wrote in his annual shareholder letter, “If a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down. Investors have poured money into a bottomless pit, attracted by growth when they should have been repelled by it.”

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

But he remained attracted. In 2016, he started buying a chunk of nearly the entire U.S. industry, eventually paying $7 billion to $8 billion to buy roughly 10% of American Airlines Group, United Airlines Holdings, Delta Air Lines, and Southwest Airlines. By 2019, he had a small profit. Then COVID-19 struck, and he immediately pulled out, calling his investments “an understandable mistake.” A year later, the stocks had taken off, with United and American more than doubling between May 1, 2020, and May 1, 2021. Such is life with airline stocks. They’re suitable only for short-term market timers, and no one—not even Warren Buffett—can time the market, knowing precisely when to jump in and out.

That is just one of the lessons that airline stocks teach. More important is the question of why, as Ben Graham predicted, they have been so lousy in the long run. If you understand the deficiencies of airlines, you can apply the wisdom more broadly.

Begin with just how poorly these stocks have performed. US Global Jets (JETS) is an exchange-traded fund that holds airline shares, with about 10% of its assets in each of the four largest U.S. carriers, another 30% in smaller international lines, and the rest in related stocks such as Boeing and Expedia. If you insist on owning a diversified portfolio of airline stocks, this is the best choice, however flawed. Over the past five years, the ETF has lost an annual average of 12%, compared with a gain of 9.3% for the broad-market S&P 500 index. (Prices and returns are as of October 7; stocks I like are in bold.)

US Global Jets was launched only in 2015. The returns of the large airlines over long periods are mostly horrendous as well. American, for example, has returned a negative 9.9% annualized over 15 years, meaning a $10,000 investment would have collapsed to roughly $2,100 over the period. United was a loser, too. Southwest, the best-run of the four largest lines, managed a return of 5.8%, compared with 8.0% for the S&P 500; Delta returned a paltry 4.1%. Since 1978, there have been well over 100 bankruptcy filings by airlines. Airlines suffered in many different years. United filed in 2002, Delta in 2005 and American in 2011. The field is littered with fabled names of the past: Pan American (bankrupt in 1998), TWA (1992 and 2002), Eastern (1989 and 1991) and Buffett’s US Airways (2002 and 2004).

So what’s the problem? There are several. Airlines are:

Too competitive. In 1978, Congress deregulated the airlines, allowing companies to set their own fares and routes—a boon to consumers, but the beginning of fare wars (and bankruptcies, as we have seen) for the lines themselves. In 1980, the average round-trip U.S. airfare was $593; today, it’s $328. After adjustment for inflation, fares have fallen 85%. Meanwhile, 381 domestic airlines are competing for business, but regulators and Congress have been reluctant to allow mergers that would give the larger ones a shot at better profitability. For example, a JetBlue Airways bid to buy low-cost carrier Spirit Airlines, even if successful, would likely face severe headwinds getting government approval.

Too commoditized. Domestic airlines have tried hard, but they can’t differentiate themselves from each other by brand. All that counts is price and timetable, so no airline can charge a premium.

Too subject to the vagaries of the price of oil. Fuel represents an average of about 20% to 25% of an airline’s total costs, and although companies can hedge the cost in the futures market, they are generally helpless to control this volatile expense.

Too capital intensive and debt ridden. Airlines need to invest heavily in planes through either purchases or leases, which means either raising equity (it’s difficult to attract investors in an industry that’s not very profitable) or issuing debt. At the end of 2021, for every $1 of equity, Delta had $19 in debt; for United, the figure was $12. Overall, the industry has a debt-to-equity ratio of about five to one, compared with one to one for all listed U.S. companies.

Too dependent on organized labor. According to Forbes, airlines represent “the most heavily unionized major U.S. industry. At American Airlines, United Airlines and Southwest Airlines, three of the four largest airlines, between 80% and 85% of the workforce is unionized. Nationwide, about 11% of the workforce is unionized.” In addition, post-COVID, airlines are facing a severe and persistent pilot shortage, as well as difficulty hiring flight attendants and other staff. This crisis has led to operational cutbacks and extra expenses for both compensation and training. Alaska Airlines, perhaps the best-managed of all the U.S. carriers, recently agreed to raise the pay of its pilots this year by 15% to 23%.

Too lacking in innovation. Planes today are actually slower than they were 40 years ago. It takes 19 minutes longer to fly from New York to Denver than it did in 1983. And that figure doesn’t count the additional time at the airport for security. Much of the innovation in flying has gone into fuel conservation—a big reason for slower planes—but technology has not done much to improve either the efficiency or the comfort of flight.

Too dependent on government. Unlike in Europe, nearly all the airports in the U.S. are run by state and local governments and thus are subject to the constraints of bureaucracy and politics. The antiquated air-traffic control system, run by a federal agency, has bedeviled airlines for decades.

For all these reasons, I urge you to stay away from airline stocks—and to apply these same lessons to the rest of your investing. But the wider aviation sector does offer opportunities to play the powerful trend of more and more of the world’s population going up in the air.

Consider Air Transport Services Group (ATSG), a diversified maintenance, leasing and cargo company whose shares have actually risen in the past year. It trades at a price-earnings ratio, based on forecasts for year-ahead profits, of 11. Shares of a similar maintenance firm, AAR (AIR), have doubled from their 2020 low but remain modestly priced. Grupo Aeroportuario del Pacifico (PAC), which I recommended in my column last month on emerging markets, operates five airports, mostly on the West Coast of Mexico. The stock has held up this year and yields 5.3%. All of these stocks are small, with market caps ranging from $1 billion to $6 billion.

If you’re having a hard time shaking your aeroholism, I’ll suggest Panama-based Copa Holdings (CPA), which flies to 29 destinations, mainly in Latin America. Founded in 1947, Copa trades at a P/E of just 9, based on projected profits. Yes, it’s an airline, but just one.

James K. Glassman chairs Glassman Advisory, a public-affairs consulting firm. He does not write about his clients. His most recent book is Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments in a Time of Turbulence. He owns none of the securities mentioned here. You can contact him at James_Glassman@kiplinger.com.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

8 Boring Habits That Will Make You Rich in Retirement

8 Boring Habits That Will Make You Rich in RetirementThese mundane activities won't make you the life of the party, but they will set you up for a rich retirement. Discover the 8 boring habits that build real wealth.

-

QUIZ: Are You Ready To Retire At 55?

QUIZ: Are You Ready To Retire At 55?Quiz Are you in a good position to retire at 55? Find out with this quick quiz.

-

10 Decluttering Books That Can Help You Downsize Without Regret

10 Decluttering Books That Can Help You Downsize Without RegretFrom managing a lifetime of belongings to navigating family dynamics, these expert-backed books offer practical guidance for anyone preparing to downsize.

-

Why I Trust These Trillion-Dollar Stocks

Why I Trust These Trillion-Dollar StocksThe top-heavy nature of the S&P 500 should make any investor nervous, but there's still plenty to like in these trillion-dollar stocks.

-

What Made Warren Buffett's Career So Remarkable

What Made Warren Buffett's Career So RemarkableWhat made the ‘Oracle of Omaha’ great, and who could be next as king or queen of investing?

-

With Buffett Retiring, Should You Invest in a Berkshire Copycat?

With Buffett Retiring, Should You Invest in a Berkshire Copycat?Warren Buffett will step down at the end of this year. Should you explore one of a handful of Berkshire Hathaway clones or copycat funds?

-

Stocks at New Highs as Shutdown Drags On: Stock Market Today

Stocks at New Highs as Shutdown Drags On: Stock Market TodayThe Nasdaq Composite, S&P 500 and Dow Jones Industrial Average all notched new record closes Thursday as tech stocks gained.

-

9 Warren Buffett Quotes for Investors to Live By

9 Warren Buffett Quotes for Investors to Live ByWarren Buffett transformed Berkshire Hathaway from a struggling textile firm to a sprawling conglomerate and investment vehicle. Here's how he did it.

-

A Timeline of Warren Buffett's Life and Berkshire Hathaway

A Timeline of Warren Buffett's Life and Berkshire HathawayBuffett was the face of Berkshire Hathaway for 60 years. Here's a timeline of how he built the sprawling holding company and its outperforming equity portfolio.

-

Berkshire Buys the Dip on UnitedHealth Group Stock. Should You?

Berkshire Buys the Dip on UnitedHealth Group Stock. Should You?Buffett & Co. picked up UnitedHealth stock on the cheap, with the embattled blue chip one of the newest holdings in the Berkshire Hathaway equity portfolio.

-

What Set Warren Buffett Apart

What Set Warren Buffett ApartAs Warren Buffett prepares for retirement, we reflect on what we've learned from his 60 years of leadership at Berkshire Hathaway.