How Heirs Can Maximize an Inherited IRA

Knowing the rules for inheriting IRAs can help avoid simple mistakes that come with big consequences.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

An IRA is a powerful vehicle to build a nest egg to fund your golden years. The account allows the money stashed inside to grow free from tax, which can turbocharge growth. With years and years of tax-advantaged, compounded growth, often there will still be money in the account when the owner dies. That money, when passed to heirs, can continue to grow in an IRA, potentially for decades into the future.

While bequeathing an IRA is pretty simple, inheriting an IRA can be a little more complicated. To make the most of inherited IRAs, it’s critical that heirs understand the rules to follow when they receive the money—and the deadlines that must be met if they want to stretch the account for years to come. All heirs aren’t the same: Spouses and nonspouses have two different sets of rules, and we’ll break the differences down.

But first and foremost, there is a key step that IRA owners need to take to give their heirs the most options for the future: Name the heirs on the account’s beneficiary form. Spouses likely would eventually inherit an IRA anyway, but it’s a simple matter to make it clear by designating a spouse on the form. For nonspouse IRA heirs, being named on the form is critical because that designation allows them to stretch out distributions from the account over their own lifetimes. If you don’t list any beneficiaries or name your estate, the IRA can’t be stretched, and the tax shelter is lost.

Article continues belowFrom just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Stretching an inherited IRA can be a huge opportunity for nonspouse heirs, says Ted Snow, a certified financial planner and founding principal of Snow Financial Group, in Addison, Tex. “Depending on the amount inherited and given enough time, the beneficiary may not have to put another dime into their own retirement because of that compounding growth” from the inherited IRA, he says. If you leave a $500,000 Roth IRA to a 40-year-old heir, by his 65th birthday, the heir would have close to $1 million tax-free if the money grew 6% a year, even after taking annual distributions, according to Schwab's online calculator.

Not only would heirs benefit from years of growth, but drawing the money out over time mitigates the tax bill produced by cashing out a traditional IRA. “If the heir takes the money out all at once, he would lose a lot to taxes,” Snow says.

One more important note for IRA owners: Keep that beneficiary form updated because the beneficiary form trumps a will. “One of the most important things to know is that an IRA passes outside of the estate,” says Maura Cassidy, vice president of retirement products for Fidelity Investments. “It passes directly to the beneficiaries.” So it’s critical that any changes you make to your will are reflected in the names you have on your beneficiary form. If you divorced and never updated your form to remove your ex-wife’s name as the sole primary beneficiary, for instance, she will get the money at your death even if your will says the money should go to your new spouse. Make it a point to review your beneficiary forms annually, Cassidy says, to ensure your money will go to your intended heirs.

When a Spouse Inherits an IRA

Surviving spouses have the most flexibility when inheriting an IRA. The surviving spouse can choose to take an inherited IRA as her own or remain a beneficiary. Or she can choose to stay a beneficiary for a while and later take the account as her own. “The only person that is allowed to roll [an inherited IRA] into her own account is the spouse,” says Cassidy.

The age of the survivor makes a big difference in the choice she makes. A young widow who hasn’t yet turned 59½ can tap an inherited IRA with no early-withdrawal penalty as a beneficiary. She likely would want to stay a beneficiary until she hits age 59½ to be able to access that resource penalty-free; once she passes 59½ and can take her own IRA withdrawals penalty-free, she can make the inherited account her own. Once a widow takes the account as her own, she won’t be subject to required minimum distributions until she turns 70½. If the account she’s left is a Roth, taking it as her own means no RMDs for her.

Most widows and widowers who are past that early-penalty hurdle will want to take the money as their own, particularly if the IRA is a Roth. Besides potentially delaying required distributions from a traditional IRA, taking the money as their own will result in smaller required distributions (more details on that later).

When a Nonspouse Inherits an IRA

For nonspouse beneficiaries—whether a child, cousin, friend or whoever—the rules for inheriting an IRA are a very different story. As designated beneficiaries, nonspouses can stretch the inherited IRA over their own lifetimes but only if they carefully follow a number of rules. Miss a step and the opportunity to make that IRA last will be gone.

The heirs must be educated on the rules to stretch an IRA because those steps can’t be taken until after the owner’s death. “One of the things owners can do is to make sure your loved ones know what your wishes are,” says Rob Williams, director of income planning for the Schwab Center for Financial Research. If you’d like your heirs to stretch the IRA, he says, “make that clear to your beneficiary; it won’t happen automatically.”

Consider having a family meeting with your financial planner to discuss your estate plans with your heirs, Snow says. When working with Mom and Dad, he says, “we want to get people inheriting the money into the conversation, too.” Many of these steps for stretching an IRA come with deadlines, so it’s helpful for heirs to know in advance how the process works.

First, a nonspouse beneficiary must rename the account to include both the beneficiary’s name and the decedent’s name, clearly identifying who’s who. For example, the account could be retitled to “Mary Smith (deceased March 1, 2018) for the benefit of Joe Smith.”

A nonspouse heir can’t roll the money into his own account, says Cassidy, nor can he convert inherited traditional IRA money to a Roth IRA. If you want your nonspouse heirs to have Roth money, you must convert the accounts before you die. The heir is stuck with whatever IRA flavor you’ve left them.

Second, to stretch an IRA over the nonspouse beneficiary’s lifetime, required minimum distributions must be taken by December 31 each year, starting in the year after the original owner died. The beneficiaries won’t pay an early-withdrawal penalty on the distributions. They will pay income tax on RMDs from inherited traditional IRAs, while RMDs from inherited Roth IRAs will be tax-free.

And that’s a key point that Roth heirs will find costly if they overlook it: While Roth IRA owners aren’t required to take distributions, nonspouse beneficiaries of inherited Roth IRAs do have RMDs if they want to stretch out the account. If an heir misses that inherited Roth RMD, he will be subject to a 50% penalty on the amount that should have been taken out, and he could blow up the potential for decades of tax-free income. It would be “very painful to find out later,” says Williams, that you were supposed to be taking distributions from the inherited Roth.

Even if heirs are inheriting taxable distributions, stretching out those distributions is likely more advantageous than cashing out the inherited IRA all at once. Nearly 40% of a sizable taxable IRA could be lost to taxes if the heir cashes it out in one fell swoop.

Besides the financial advantages of stretching out distributions, an heir might find an emotional benefit as well. Cassidy says she knows an IRA heir who considers each annual distribution as a birthday present from his deceased parent.

If multiple nonspouse beneficiaries are named, each beneficiary can stretch her distributions over her own lifetime—but only if the account is split in a timely manner, Cassidy says. The inherited IRA must be split by December 31 of the year following the year the owner died. Each beneficiary retitles her share of the IRA and can then stretch out distributions over her lifetime.

If the account isn’t split, the life expectancy of the oldest beneficiary must be used to calculate RMDs. That makes a big difference if the beneficiaries have a wide age gap, because the younger the heir, the smaller the RMDs would be. Say a 60-year-old son and a 22-year-old granddaughter are named heirs to a traditional IRA. Separating the accounts would set the 22-year-old’s first RMD at 1.6% of the account balance, compared with a 4% withdrawal required for the 60-year-old. Splitting means more of her money can stay in her inherited IRA to grow free of tax.

By splitting the inherited account, each beneficiary can also name her own successor beneficiaries. And each can choose her own investment strategy.

What if a charity or other nonperson beneficiary is named, too? That nonperson share should be paid out by September 30 of the year following the year the owner died. If it’s not, the people named as beneficiaries lose the opportunity to stretch out the IRA over their own life expectancies. Instead, the beneficiaries would have to take out all assets within five years of the owner’s death if the owner died before age 70½. If the owner died after that age, beneficiaries would have to take annual withdrawals based on the deceased’s remaining life expectancy, as set out in IRS tables.

Note that any heir who thinks the IRA would be better maximized by the next beneficiary in line can disinherit his interest in the IRA. Say a son is named primary beneficiary while his children are named contingent beneficiaries. He could “disclaim” the IRA, and it will pass to the contingent beneficiaries.

You must typically make the irrevocable decision to disclaim within nine months of the original owner’s death, and you cannot have taken control of the assets before deciding to disclaim. You don’t get to pick where your interest in the IRA goes—it will go to the next in line according to the beneficiary form.

All RMD Calculations Aren’t the Same

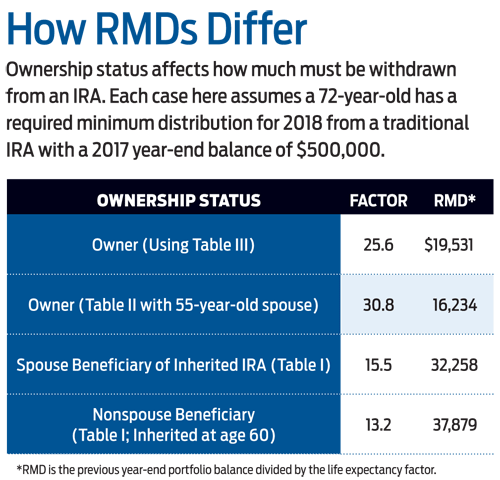

The final tip that heirs need to be aware of: Their RMD calculations aren’t the same as the original owner’s. Your ownership status determines how much you must take out every year. The calculations vary for owners and beneficiaries, for example, and for nonspouse beneficiaries and spouses who remain beneficiaries.

For original owners as well as spouse heirs who roll inherited money into their own name, the RMD is figured by referring to Table III (the Uniform Lifetime Table) in IRS Publication 590-B to find the life expectancy factor that correlates to the person’s birthday for the year. Then the IRA account balance as of December 31 of the previous year is divided by that factor, which is based on remaining life expectancy, to arrive at the required minimum withdrawal amount. Note that if an owner has a spouse who’s more than 10 years younger, he can use a different table to take out a smaller RMD to account for the younger spouse’s longer life expectancy.

Beneficiaries will have larger distributions. They use Table I in Publication 590-B, but the exact calculation depends on the type of heir. While a spouse who stays a beneficiary gets to recalculate life expectancy each year, nonspouse beneficiaries don’t. Instead, the nonspouse consults Table I for his first RMD, using the factor based on his age at that time. (Table I is based on single life expectancy and results in bigger RMDs than Table III, which owners use.) Then for each subsequent year’s distribution, the nonspouse heir subtracts one from that factor. For example, a 55-year-old nonspouse heir would use a factor of 29.6 from Table I.

For his second RMD, he uses 28.6, instead of the table’s factor of 28.7 for age 56. By the time he reaches age 75, he will use a factor of 9.6 instead of the table’s 13.4. The smaller factor means he takes out more.

Take a look at the chart below and you’ll see the difference in how the numbers shake out even when the age of the person withdrawing is the same. The nonspouse beneficiary has the largest RMD, while the spouse beneficiary has the second-largest and a larger RMD than she would as the owner. The owner takes out less than the beneficiaries, while the owner with a spouse who is more than 10 years younger has the smallest RMD of all.

Whatever type of owner you are, it’s critical to use the right table and calculation. If you don’t, you could take out more than you need to. Or worse, you could take out less than required and get hit with the 50% missed RMD penalty on the shortfall.

Knowing the rules for inheriting IRAs can help owners and heirs avoid simple mistakes that come with big consequences. And that knowledge lets you and your loved ones squeeze the most out of the IRA tax shelter for years, and potentially decades, to come.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.