Investors, Stop Worrying About a Bear Market

It's not like there aren't risks out there, but the smart strategy is to stay in stocks, and stay diversified.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

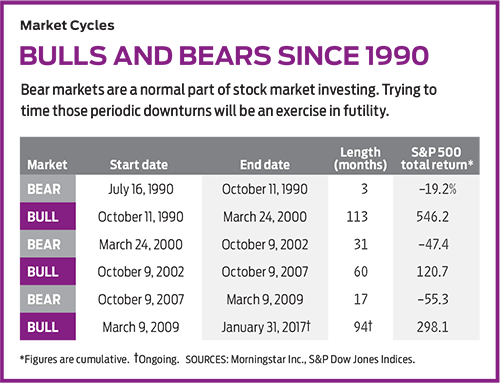

Want to kick yourself? Just look at what you would have paid for shares of some terrific companies in early 2009. Southwest Airlines (symbol LUV) was trading at less than $6; it’s now $52. American Express (AXP) has gone from $12 to $76; Home Depot (HD), from $21 to $138; eBay (EBAY), from $5 to $32. It’s no secret that the U.S. has been experiencing a massive bull market. It began on March 9, 2009, when Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index closed at 677, having sunk from 1565 just 17 months earlier.

As I write, the S&P has returned 298% (including dividends) since that bottom. In other words, if you had put $100,000 into the market in the spring of 2009, you would have more than $400,000 today. The bull market is now the second-longest since the Great Depression and boasts the third-largest total gain. On a total-return basis, the market has risen eight straight calendar years, one year shy of the record set from 1991 through 1999. Except for a blip in July 2015, the VIX, an index that measures the volatility of the S&P 500, has been strikingly low for five years.

Still, bull markets make me nervous. They always end, and the big ones tend to end especially badly. By the end of the bull market of 1982–87, for example, the S&P 500 had returned 266%, but within three months the market lost 27%. During the fabulous technology-driven bull market of the 1990s, the S&P 500 soared more than 540%. But after the bull departed, the S&P plunged 47% between March 2000 and October 2002.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Bull markets usually end for one of two reasons: Either investors bid up share prices to well beyond what they are worth, or something fundamentally bad happens to the economy. Let’s look at each of those scenarios.

During the 2007–09 economic and stock market debacle, investors learned that the value of their nicely diversified holdings could be chopped in half quickly. Despite the recovery, investors’ fears have, remarkably, not dissipated. Consider the total assets that investors hold in stock mutual funds. At the end of 2007, when the market was near its peak, the figure was $6.4 trillion. At the end of 2016, it was $8.6 trillion, an increase of just 34%, even though the S&P had returned 50% over the period. If investors who had their money in stock funds at the end of 2007 had simply kept their money where it was and added nothing new, total assets would have roughly risen by half again as much as they actually did.

What happened? Investors have been taking money out of stock funds and putting it into hybrid funds (generally, those that own stocks and bonds), bond funds, money market funds and other assets. According to the Investment Company Institute, the fund industry’s trade group, investors have pulled more money out of stock funds than they’ve put in every month from March 2016 through January 2017. The net outflow since 2008 has been more than a half trillion dollars. One reason for the withdrawals is that many Americans are reaching retirement age; another is the rise of stock-owning exchange-traded funds.

Still frightened. But the biggest part of the story is that investors remain spooked by stocks. The latest figures from the Employee Benefit Research Institute show that, on average, investors hold only a little more than half of their IRA assets in stocks or stock funds. And for all investors, total assets in bond mutual funds have doubled since 2007, despite historically low interest rates.

I find it troubling that investors have not put more money into stocks, but the lack of enthusiasm among investors is good news. It means that cash and assets in bond funds remain on the sidelines, ready to be deployed into stocks and push up their prices. Also good news is the market’s valuation. A recent T. Rowe Price report found that the S&P 500’s price-earnings ratio of 17 (based on estimated 2017 earnings) was only about 10% higher than the market’s average P/E of the past 15 years. Share prices are certainly not in the danger zone.

What about the economy? It has expanded in each of the past eight years, though growth has been sluggish (averaging just 2.1% annually). And inflation has been moderate enough to keep interest rates low. Unemployment has fallen sharply, and wages have picked up. Meanwhile, President Trump is aiming for annual growth of 3% to 4%; to achieve it, he wants to reduce taxes and regulations, boost spending, and change our trade policies.

Bright prospects. Lucy O’Carroll, chief economist for Aberdeen Asset Management, believes that current stock prices reflect the hope that Trump’s policies will, on balance, work—or, more precisely, that the “good” parts of his agenda for business (such as tax cuts) will outweigh the “bad” (trade protection). Investors might be “over-optimistic,” she tells me, but prospects for profit growth are what really drive stock prices, and those prospects, she says, are both bright and buttressed by reality.

And yet … there’s a more unpleasant scenario. A combination of increased spending, lower tax revenues and higher borrowing costs could lead to an explosion of the federal deficit. If you combine an expanding deficit with upward pressure on wages from an economy that is nearly at full employment, you get rising inflation. The Federal Reserve has already been hiking interest rates, and at some point higher rates could choke off economic activity and cause a recession, which would almost certainly result in a bear market.

Another potential problem is trade. President Trump has already killed the Trans-Pacific Partnership and has started to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement. Lowering trade barriers facilitated the post–World War II economic boom. If tariffs start to rise again, the risks could be substantial.

Finally, there is the simple long-in-the-tooth argument. The duration of both the economic expansion and the bull market is exceptional. As of early February, the U.S. had gone 91 months without a recession—the third-longest expansion since 1854, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research. Longevity is worrisome.

But what can you do about it? In my view, nothing. No one can consistently forecast the future of the economy or the course of markets with accuracy, but the weight of the evidence is on the side of the bull market continuing. The smart strategy, then, is to stay in stocks and stay diversified.

You can’t go wrong owning the S&P itself, through such vehicles as Vanguard 500 Index (VFINX), the world’s third-largest mutual fund, with $233 billion in assets, or iShares Core S&P 500 ETF (IVV), the exchange-traded fund equivalent. Among actively managed funds that have a good chance of beating the S&P by a percentage point or two per year, my longtime favorites include Dodge & Cox Stock (DODGX), Fidelity Contrafund (FCNTX), T. Rowe Price Blue Chip Growth (TRBCX) and Parnassus Core Equity (PRBLX), which has a socially responsible investing portfolio. (The Price and Dodge & Cox funds are members of the Kiplinger 25.)For individual stocks, I lean toward financials, which I recommended in my October 2016 column. They were cheaper then, but I still like such companies as JPMorgan Chase (JPM, $85), with a P/E, based on estimated 2017 earnings, of 13; Bank of America (BAC, $23), up 58% since my column but carrying a forward P/E of only 13, even though earnings are expected to rise this year by 25%; and London-based HSBC Holdings (HSBC, $43), with extensive business in Asia and a luscious 4.7% dividend yield.

Of course, you should leaven your portfolio with bonds and cash for medium- and short-term needs, such as making a down payment on a house or paying your living costs in retirement. But stocks—especially U.S. equities—remain the best place for your money, even in the ninth year of a running bull.

James K. Glassman, a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise institute, is the author, most recently, of Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments in a Time of Turbulence. Of the stocks mentioned, he owns HSBC.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayAnother worrying bout of late-session weakness couldn't take down the main equity indexes on Wednesday.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

How Inflation, Deflation and Other 'Flations' Impact Your Stock Portfolio

How Inflation, Deflation and Other 'Flations' Impact Your Stock PortfolioThere are five different types of "flations" that not only impact the economy, but also your investment returns. Here's how to adjust your portfolio for each one.

-

Why I Still Won't Buy Gold: Glassman

Why I Still Won't Buy Gold: GlassmanOne reason I won't buy gold is because while stocks rise briskly over time – not every month or year, but certainly every decade – gold does not.

-

Should You Use a 25x4 Portfolio Allocation?

Should You Use a 25x4 Portfolio Allocation?The 25x4 portfolio is supposed to be the new 60/40. Should you bite?

-

Retirement Income Funds to Keep Cash Flowing In Your Golden Years

Retirement Income Funds to Keep Cash Flowing In Your Golden YearsRetirement income funds are designed to generate a reliable cash payout for retirees. Here are a few we like.

-

10 2024 Stock Picks From An Investing Expert

10 2024 Stock Picks From An Investing ExpertThese 2024 stock picks have the potential to beat the market over the next 12 months.

-

Special Dividends Are On The Rise — Here's What to Know About Them

Special Dividends Are On The Rise — Here's What to Know About ThemMore companies are paying out special dividends this year. Here's what that means.

-

How to Invest in AI

How to Invest in AIInvestors wanting to know how to invest in AI should consider these companies that stand to benefit from the boom.

-

Why I Still Like Emerging Markets

Why I Still Like Emerging MarketsPeriods of global instability create intriguing possibilities in emerging markets. Here are a few.