Think Twice Before You Close a Credit Card

Even if you’re no longer using it, closing an account could ding your credit score.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Paying off high-interest credit card debt is an important step toward financial freedom, and Americans have taken this standard personal finance advice to heart. According to data from the Federal Reserve, revolving credit balances (primarily credit card debt) dropped more than 11% from 2019 to 2020. Analysts believe the decline stems from a combination of spending cutbacks during the pandemic and billions of dollars in stimulus checks, which many consumers used to pay off debt.

If you find yourself with one or more paid-off credit cards taking up wallet space, should you close your accounts for good?

Credit-utilization math. Most experts agree that you should hold on to a paid-off credit card, even if you’re no longer using it. FICO scores, which most lenders use, are calculated based on five factors with varying weights. Your payment history is the most important factor, accounting for 35% of your score, but your credit-utilization ratio—the amount you owe as a percentage of your total available credit—also has a heavy impact on your score, at 30%.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Say you have total available credit of $10,000 split evenly between two cards. One card has a balance of $2,500 and the other has a zero balance because you paid it off. Your credit-utilization ratio is 25%—a desirable amount because most credit experts recommend keeping the ratio under 30%. If you were to close that zero-balance card, though, your ratio would jump to 50%, which would hurt your credit score.

In addition to doing the math with your own accounts before you close a card, you also need to give some thought to why you no longer want the card, says credit expert Beverly Harzog, author of The Debt Escape Plan. Harzog says people most often consider closing a credit card when the rewards aren’t generous enough to justify the annual fee or when they want to remove a temptation to run up more debt. But you may not need to close a card to address those issues.

New card, same issuer. Cards with annual fees often offer rewards—but at a steep price. Such cards will typically cost you about $100 a year, but some can run as high as $550 (see Best Rewards Credit Cards).

If you are reconsidering a card with a high annual fee, ask the issuer if it has a no-fee (or low-fee) card with similar rewards and credit limits you can switch to. If you’re approved, you won’t lose the credit history attached to the old card, and your credit-utilization ratio won’t be affected.

If you can’t find a card to switch to with the same issuer, apply for a new card with a similar credit limit before canceling the old card. That way, your credit score won’t take a prolonged hit, because the amount of your available credit will remain the same.

If want to remove the temptation to spend, store the card in a safe place where you won’t come across it very often. Or just cut it up. Once you’ve done that, prevent crooks from using it by going to your credit card’s website or app and placing a lock on your account.

“If you truly believe canceling a card is in your best interest, do it, and just ride it out,” Harzog says. The hit to your score will be temporary as long as you continue to keep your card balances low and pay your bills on time.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Rivan joined Kiplinger on Leap Day 2016 as a reporter for Kiplinger's Personal Finance magazine. A Michigan native, she graduated from the University of Michigan in 2014 and from there freelanced as a local copy editor and proofreader, and served as a research assistant to a local Detroit journalist. Her work has been featured in the Ann Arbor Observer and Sage Business Researcher. She is currently assistant editor, personal finance at The Washington Post.

-

Dow Absorbs Disruptions, Adds 370 Points: Stock Market Today

Dow Absorbs Disruptions, Adds 370 Points: Stock Market TodayInvestors, traders and speculators will hear from President Donald Trump tonight, and then they'll listen to Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang tomorrow.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Maximize Your Social Security Check?

Quiz: Do You Know How to Maximize Your Social Security Check?Quiz Test your knowledge of Social Security delayed retirement credits with our quick quiz.

-

Will You Get a Trump Tariff Refund in 2026? What to Know Now

Will You Get a Trump Tariff Refund in 2026? What to Know NowTax Law The Supreme Court's tariff ruling has many wondering about refund rights and how tariff refunds would work.

-

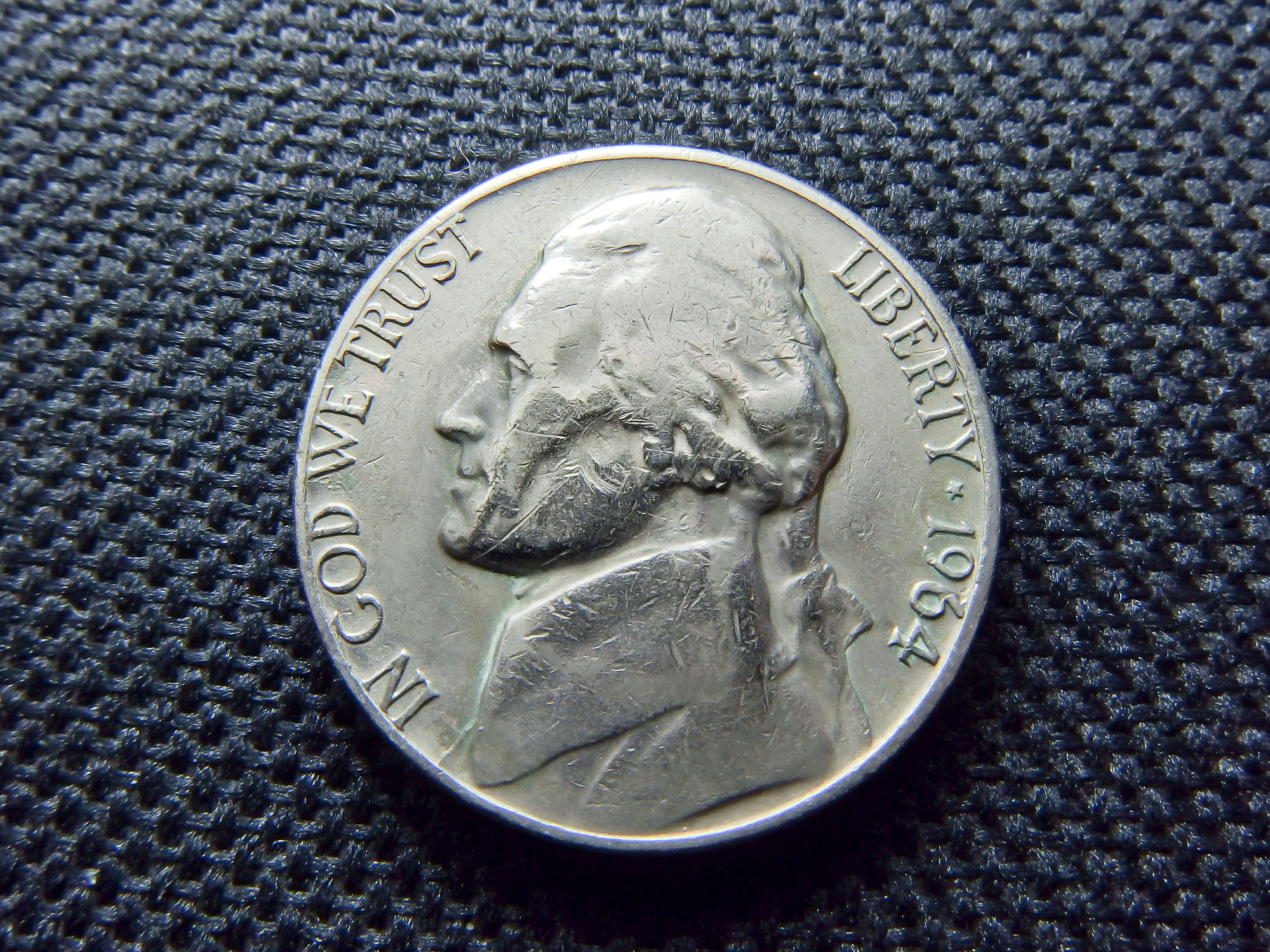

First the Penny, Now the Nickel? The New Math Behind Your Sales Tax and Total

First the Penny, Now the Nickel? The New Math Behind Your Sales Tax and TotalRounding Tax A new era of "Swedish rounding" hits U.S. registers soon. Learn why the nickel might be on the chopping block, and how to save money by choosing the right way to pay.

-

Big Change Coming to the Federal Reserve

Big Change Coming to the Federal ReserveThe Lette A new chairman of the Federal Reserve has been named. What will this mean for the economy?

-

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next Move

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next MoveThe December CPI report came in lighter than expected, but housing costs remain an overhang.

-

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't Need

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't NeedFinancial Planning If you're paying for these types of insurance, you might be wasting your money. Here's what you need to know.

-

The November CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for Rising Prices

The November CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for Rising PricesThe November CPI report came in lighter than expected, but the delayed data give an incomplete picture of inflation, say economists.

-

The Delayed September CPI Report is Out. Here's What it Signals for the Fed.

The Delayed September CPI Report is Out. Here's What it Signals for the Fed.The September CPI report showed that inflation remains tame – and all but confirms another rate cut from the Fed.

-

Banks Are Sounding the Alarm About Stablecoins

Banks Are Sounding the Alarm About StablecoinsThe Kiplinger Letter The banking industry says stablecoins could have a negative impact on lending.

-

21 Last-Minute Gifts for Grandparents Day 2025 to Give Right Now

21 Last-Minute Gifts for Grandparents Day 2025 to Give Right NowHoliday Tips Last-minute gifting is never easy. But here are some ideas to celebrate Grandparents Day.