Thanks, Granny: Money Quirks (Good or Bad) Can Be Inherited

To learn about your own financial strengths and help eliminate your weaknesses, trace your family tree.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

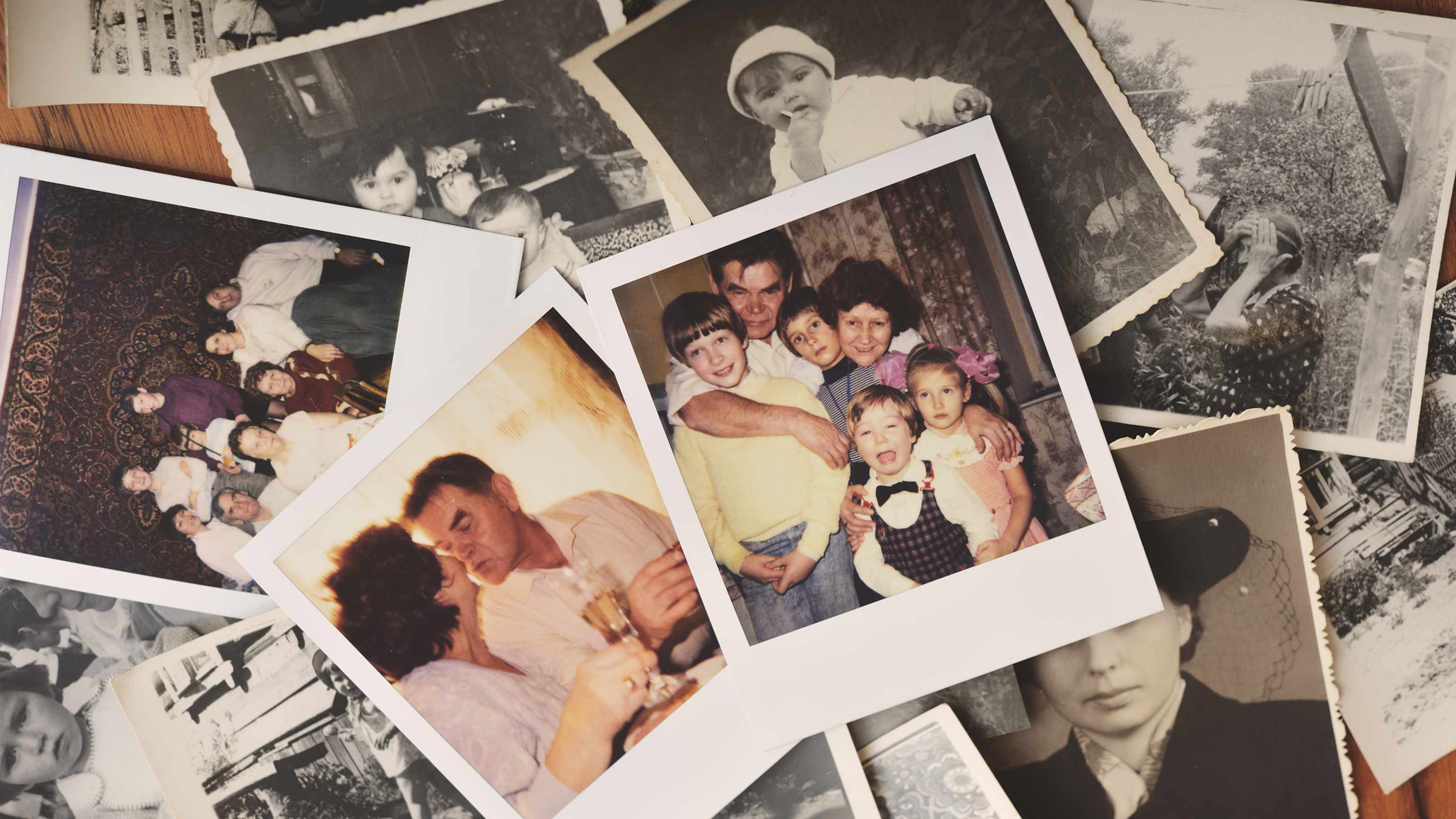

Dad was a spender, and Mom was a saver. My parents, Depression-era babies, kept a jar of dollar bills behind the fridge for when the banks crashed. My grandparents were immigrants, and in our family homeownership is priority No. 1, no matter what the interest rates or other debt you have.

We all have these stories — the epic narrative of our family’s financial background.

Like short tempers and a sweet tooth, money habits are at least in some part inherited and influence our behavior, whether we like it or not. Do you find yourself unable to sleep at night with even the smallest debt on the books? Do you overspend on status items (new cars, fresh clothes) while your credit card bill gathers interest?

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

These behaviors are part of a story — a narrative that’s been going on since before you were born.

How My Family’s Financial History Influenced My Own Money Habits

To this day I can still picture every detail of my Smurf bedroom. I loved that bedroom. It also happened to be in a trailer park. It's the first home I clearly remember. When I was born, my parents were practically teenagers, without anything resembling a financial strategy.

I grew up with the reality that hard work and education were our only defenses against poverty. Even though my parents didn’t know the finer points of financial aid and college prep, they pushed me toward this goal with both hands.

Now I find myself comfortable financially, but living well below my means, afraid to part with money. I have a decent four-bedroom house and a car I plan to drive until the wheels fall off. I rarely eat fast food and would rather take a few small vacations a year than a single audacious one. My financial life could be different, but the invisible script I absorbed growing up tells me to keep it simple, because “you never know.”

What Does Your Family’s Financial History Mean for You?

We can look back on our family story to know ourselves and our families better. The most unreflective impulse we have when we think of money is simply to have more of it. To stop the discussion there is to misunderstand ourselves.

You will have a relationship with money your whole life, and the many sides of this connection — from BFF to “frenemy” — are much more complex than simply wanting more. Looking at how you react to cash can give you insight into yourself and into improving this relationship in the years to come.

How to Map Your Own Family’s Financial History

One helpful model for tracing back your personal history is the family financial genogram — it’s like a family tree diagram, but with finances in mind. To explore your own family’s financial history, three questions guide the process:

- Family patterns: How did your parents handle money? Your grandparents? Did any historical events (Great Depression, war, etc.) affect the way they behaved financially?

- Financial obstacles: What kind of financial difficulties has your family faced?

- Family rules: What were your family’s “messages” and “rules” about money?

Answering these questions can help you diagnose your financial behavior, which is the first step toward changing negative behaviors and reinforcing positive ones.

An Example: Jane SpendThrift

Jane SpendThrift’s paternal grandparents were immigrants from a politically troubled, impoverished country in Europe. They worked seven days a week and counted out their paychecks to the nickel, continuing that behavior even when they did well financially.

Jane’s father went in the opposite financial direction, spending much more freely. He married a woman whose Depression-era parents also pinched every penny, and she ended up with a similar reaction to her upbringing. Jane’s parents embraced their baby boomer identity with new motorcycles and trips to Vegas and Disney, tossing a token amount in savings with no plan.

From her grandparents, Jane learned that a “penny saved is a penny earned.” From her parents, Jane learned life is short, and he who dies with the most toys wins.

So where does Jane end up? She finds herself working extremely hard, so she never has to wonder how to pay rent or utilities, like her family did for a few months in 2008. She stresses about finances constantly, even when she’s doing fine, and leads an imbalanced life to keep her books balanced.

She pays her bills, keeps a zero rollover on her credit cards, yet never finds herself able to build lasting wealth.

Thinking through her family history, she sees how her grandparents’ and parents’ stories have woven into her own. She talks it over with her adviser and some close friends and realizes that her long-term financial dream is stability, but her short-term stress relief valve is spending.

She goes home to a closet full of new dresses purchased after a breakup and drives a new car she bought shortly after she was laid off, an impulse purchase with a high-interest loan.

Break it down like this:

- Family patterns: Immigrant grandparents taught her the value of hard work. Parents taught her that relaxing means spending.

- Financial obstacles: Her grandparents changed cultures, faced a language barrier and started over. The 2008 financial crash she witnessed as a teen affected her psychology with the scary reality of financial hardship.

- Family rules: Jane is sandwiched between her grandparents, who treated money with a nervous solemnity, and her parents, who flaunted it with little thought. Her relationship with money is complex and evasive.

Jane SpendThrift is young, but her issues could multiply over the next 20 years if she doesn’t develop better habits. In middle age, Jane could have minimal savings, having hardly started on her 401(k) strategy. She might find herself unable to help her kids with the cost of college, sending them into adulthood on the wrong foot.

Instead, Jane Spendthrift takes action. She calls her adviser and sets up a plan to create an emergency fund while strategically paying off high-interest versus low-interest debt. She also gets a gym membership and sees a life coach to develop better coping strategies to manage stress.

Armed with this awareness, she recovers from stressful events surrounded by friends, enjoying a simple evening at a favorite restaurant, instead of binge spending.

Learning from the COVID-19 Financial Crisis

What will show up on the financial genograms in 2040? Will our kids and grandkids have a compulsive need to double their emergency funding, because they remember a parent suddenly laid off during quarantine? Will they be acutely sensitive to volatility, because of the ups and downs we’ve weathered this year? There’s no telling for sure, but “knowing is half the battle,” as GI Joe used to say.

Now, when we are in the middle of a life-transforming event, is the time to become aware of how personal and global events shaped our story and the grand narrative of our family. To know this is to know ourselves, and to know ourselves is to build a better future for the next generation.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Erin Wood has over two decades of experience humanizing financial planning. As SVP of Advanced Planning at AssetMark, Erin leads innovation for new wealth solutions, secures strategic industry relationships and oversees a team of specialists who work directly with advisers and their high-net-worth clients. Erin focuses on delivering tailored strategies for estate planning, tax efficiency, retirement planning and multigenerational wealth transfer to help financial advisers keep up with evolving client demands.

-

Thinking of Switching Phone Carriers? Do These 8 Things First

Thinking of Switching Phone Carriers? Do These 8 Things FirstSwitching carriers is easier than ever, but overlooking the fine print could cost you. Here’s what to check before you make the move.

-

Samsung Galaxy S26 Ultra: What to Know Before You Upgrade

Samsung Galaxy S26 Ultra: What to Know Before You UpgradeThe Galaxy S26 Ultra brings new features and strong launch deals, but whether it’s worth upgrading depends on what you already own.

-

Nasdaq Soars Ahead of Nvidia Earnings: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Soars Ahead of Nvidia Earnings: Stock Market TodayWednesday's risk-on session was sparked by strong gains in tech stocks and several crypto-related names.

-

Your Retirement Age Is Just a Number: Today's Retirement Goal Is 'Work Optional'

Your Retirement Age Is Just a Number: Today's Retirement Goal Is 'Work Optional'Becoming "work optional" is about control — of your time, your choices and your future. This seven-step guide from a financial planner can help you get there.

-

Have You Fallen Into the High-Earning Trap? This Is How to Escape

Have You Fallen Into the High-Earning Trap? This Is How to EscapeHigh income is a gift, but it can pull you into higher spending, undisciplined investing and overreliance on future earnings. These actionable steps will help you escape the trap.

-

I'm a Financial Adviser: These 3 Questions Can Help You Navigate a Noisy Year With Financial Clarity

I'm a Financial Adviser: These 3 Questions Can Help You Navigate a Noisy Year With Financial ClarityThe key is to resist focusing only on the markets. Instead, when making financial decisions, think about your values and what matters the most to you.

-

It's Time to Bust These 3 Long-Term Care Myths (and Face Some Uncomfortable Truths)

It's Time to Bust These 3 Long-Term Care Myths (and Face Some Uncomfortable Truths)None of us wants to think we'll need long-term care when we get older, but the odds are roughly even that we will. Which is all the more reason to understand the realities of LTC and how to pay for it.

-

Fix Your Mix: How to Derisk Your Portfolio Before Retirement

Fix Your Mix: How to Derisk Your Portfolio Before RetirementIn the run-up to retirement, your asset allocation needs to match your risk tolerance without eliminating potential for growth. Here's how to find the right mix.

-

An Executive's 'Idiotic' Idea: Skip Safety Class and Commit a Federal Crime

An Executive's 'Idiotic' Idea: Skip Safety Class and Commit a Federal CrimeSeveral medical professionals reached out to say that one of their bosses suggested committing a crime to fulfill OSHA requirements. What's an employee to do?

-

How You Can Use the Financial Resource Built Into Your Home to Help With Your Long-Term Goals

How You Can Use the Financial Resource Built Into Your Home to Help With Your Long-Term GoalsHomeowners are increasingly using their home equity, through products like HELOCs and home equity loans, as a financial resource for managing debt, funding renovations and more.

-

How to Find Free Money for Graduate School as Federal Loans Tighten in 2026

How to Find Free Money for Graduate School as Federal Loans Tighten in 2026Starting July 1, federal borrowing will be capped for new graduate students, making scholarships and other forms of "free money" vital. Here's what to know.