State Estate Taxes Not Dead Yet

States are starting to beef up their estate tax laws instead of tearing them down. Is your state one of them?

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

To paraphrase Mark Twain: reports of the death of state estate taxes are greatly exaggerated. In fact, there are recent signs that states are starting to beef up their estate tax laws instead of tearing them down. This, of course, is bad news for wealthier Americans, who had hoped that state lawmakers would continue burying these taxes.

But all is not lost for retirees who have accumulated assets over the years. A majority of states don’t have their own death taxes, and for those that do, at least the trend toward higher exemption amounts is continuing in several states. So, while you shouldn’t hold your breath waiting for your state’s estate tax to be repealed, you still might be able to avoid the tax in the end.

The Road to Extinction

Back in 2000, every state and the District of Columbia imposed an estate tax. And why not? The federal estate tax law allowed a dollar-for-dollar credit for up to 16% of state estate and inheritance taxes paid. That, in essence, allowed states to levy their own estate taxes without imposing any additional tax burden on their residents. It was a no-brainer for the states.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

But that all started to change in 2001. Legislation enacted that year gradually eliminated the federal credit (it was completely repealed in 2005). From that point on, if a state wanted to impose an estate tax, it meant “extra” taxes on resident estates beyond the federal tax hit. Nevertheless, more than 20 states went down that road. But the fear of wealthy residents moving elsewhere because of the added tax burden ultimately triggered a wave of estate tax repeal measures in many of those jurisdictions. For a time, it looked like state estate taxes might go the way of the dinosaur.

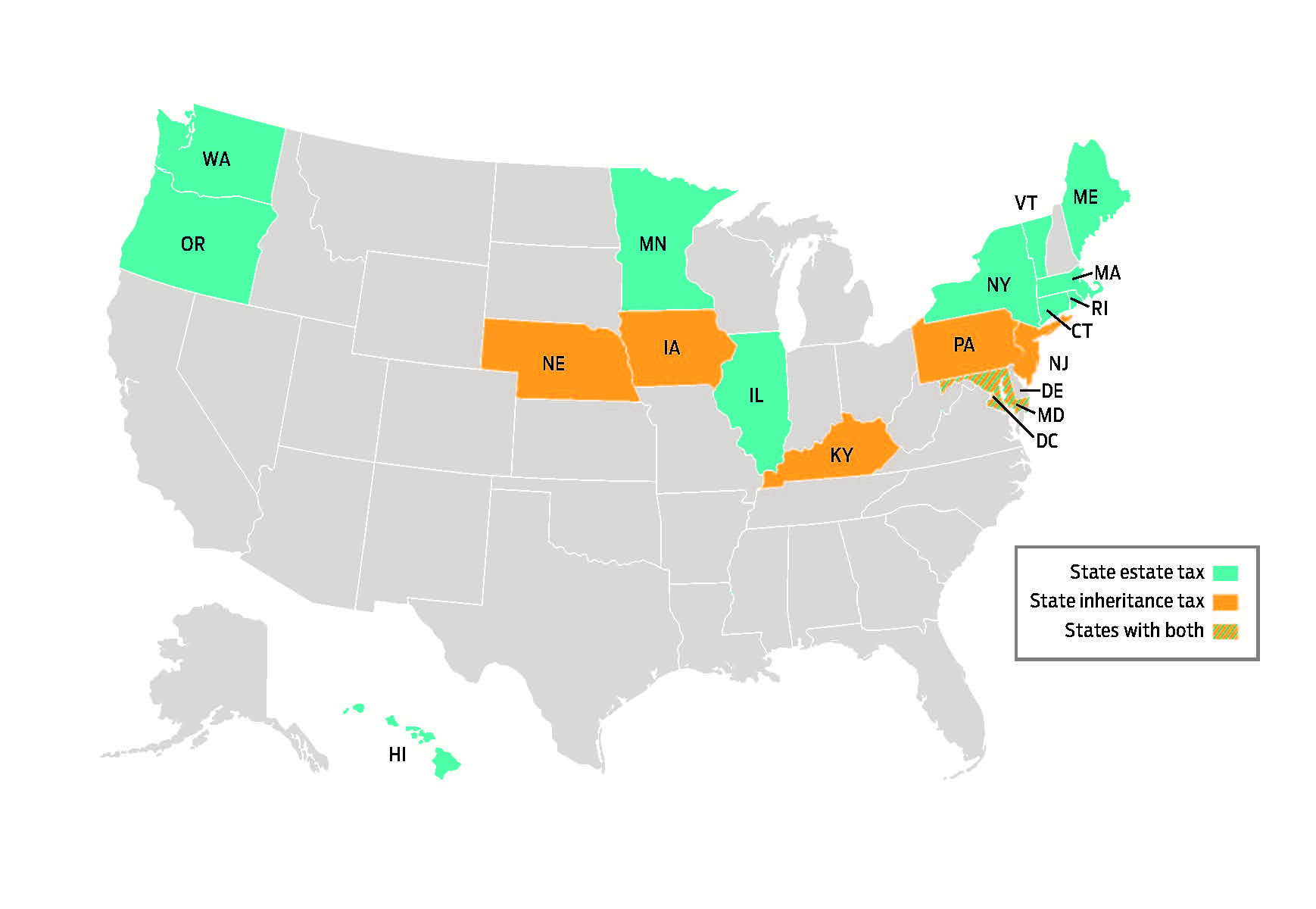

Things have slowed down a bit for now, though. Delaware and New Jersey repealed their estate taxes beginning in 2018. However, since then, no other state has gotten rid of its estate tax—leaving 12 states and the District of Columbia that still impose the tax. One reason may be that states are worrying less these days about losing wealthy residents. A recent study by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggests that, in the long run, states are better off keeping their estate tax even if some wealthy residents move elsewhere because of it. The study concludes that, for most states, the “one-time tax revenue gain when a wealthy resident dies” exceeds the “foregone income tax revenues over the remaining lifetime of those who relocate.”

A few states are even tightening up or enhancing their estate tax laws. For instance, Bruno Graziano, senior analyst at Wolters Kluwer Tax & Accounting, notes that Connecticut passed a “loophole closer” in 2019 that cracks down on “nonresidents who were placing properties in pass-through entities to try to escape the estate tax.” Hawaii also added what he describes as a “surtax” on estates worth more than $10 million. And New York renewed a “claw back” feature that Graziano says will “tax gifts that were made within three years of death.”

Exemption Amounts Continue to Rise—To a Point

While state estate taxes might not be completely on the way out, the trend of subjecting fewer estates to the tax continues. Estate-tax exemption amounts are rising in 2020 in half the states with the tax. Inflation adjustments account for slight exemption increases this year in Maine ($5.7 million to $5.8 million), New York ($5.74 million to $5.85 million) and Rhode Island ($1,561,719 to $1,579,922). Larger 2020 increases in Connecticut ($3.6 million to $5.1 million), Minnesota ($2.7 million to $3 million) and Vermont ($2.75 million to $4.25 million) are a result of recent legislation.

Most states aren’t willing to raise their exemption amount too high, though. New York’s $5.85 million exemption is the highest so far for 2020. Plus, the lowest exemption amounts—in Massachusetts and Oregon—are holding steady at $1 million this year.

And don’t look for many states to boost their exemption amount to the current federal level, which is $11.58 million for 2020 ($23.16 million for married couples). Before 2018, matching or at least approaching the federal amount was not uncommon. However, when the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 doubled the federal amount, Graziano believes that was “a bridge too far” for most states. The states were “willing to follow the feds to a certain point,” he says, “but now they’re kind of pushing back a little bit.”

States are also being cautious because the enhanced federal exemption amount is only temporary. In 2026, the federal exemption is scheduled to drop back down to $5 million (adjusted for inflation). However, no one knows if the law will change before then. That’s putting states in a “holding pattern” right now, says Graziano, while they “wait to see what’s going to happen on the federal end.”

States aren’t jumping on the “portability” bandwagon, either. By electing portability at the federal level, a deceased spouse’s unused estate-tax exemption amount is transferred to the surviving spouse. This effectively doubles the exemption amount for the surviving spouse’s estate and prevents the first deceased spouse’s exemption from being wasted. However, on the state level, only Hawaii and Maryland currently offer portability for their estate-tax exemptions, and there are no indications at this time that other states will join them.

Don’t Forget About Inheritance Taxes

Even if you escape state estate taxes, your heirs still might have to pay state inheritance taxes. While estate taxes are paid by the estate and based on the estate’s overall value, inheritance taxes are paid by an individual heir on whatever property they inherit.

Six states currently impose an inheritance tax—Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey and Pennsylvania—and rates can be as high as 18%. (Maryland has both an estate tax and an inheritance tax.) So make sure you consider this potential tax in your estate planning.

However, even if your state has an inheritance tax on the books, certain relatives who inherit your property still might not have to pay it. There’s a good chance your closest kin will be exempt from the tax when you die, while more distant family members probably won’t be so lucky. For example, in Iowa, a decedent’s spouse, parents, children and grandchildren don’t have to pay the state’s inheritance tax. But other heirs, such as nieces, nephews, uncles, aunts and non-relatives, do have to pay.

State inheritance tax rates can also be higher for more distant relatives or for more valuable property. In Nebraska, for instance, the tax on heirs who are immediate relatives is only 1% and does not apply to property that’s worth less than $40,000. For remote relatives, the tax rate is 13% and the exemption amount is $15,000. For all other heirs, the tax is imposed at an 18% rate on property worth $10,000 or more.

For more details on death taxes in the states that levy them, check out Kiplinger’s Retiree Tax Map.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Rocky Mengle was a Senior Tax Editor for Kiplinger from October 2018 to January 2023 with more than 20 years of experience covering federal and state tax developments. Before coming to Kiplinger, Rocky worked for Wolters Kluwer Tax & Accounting, and Kleinrock Publishing, where he provided breaking news and guidance for CPAs, tax attorneys, and other tax professionals. He has also been quoted as an expert by USA Today, Forbes, U.S. News & World Report, Reuters, Accounting Today, and other media outlets. Rocky holds a law degree from the University of Connecticut and a B.A. in History from Salisbury University.

-

Why Some Michigan Tax Refunds Are Taking Longer Than Usual This Year

Why Some Michigan Tax Refunds Are Taking Longer Than Usual This YearState Taxes If your Michigan tax refund hasn’t arrived, you’re not alone. Here’s what "pending manual review" means and how to verify your identity if needed.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Caterpillar Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Caterpillar Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayCaterpillar stock has been a remarkably resilient market beater for a very long time.

-

Good Stock Picking Gives This Primecap Odyssey Fund a Lift

Good Stock Picking Gives This Primecap Odyssey Fund a LiftOutsize exposure to an outperforming tech stock and a pair of drugmakers have boosted recent returns for the Primecap Odyssey Growth Fund.

-

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't Need

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't NeedFinancial Planning If you're paying for these types of insurance, you might be wasting your money. Here's what you need to know.

-

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online Bargains

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online BargainsFeature Amazon Resale products may have some imperfections, but that often leads to wildly discounted prices.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits in 2026. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.

-

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026SEP IRA A good option for small business owners, SEP IRAs allow individual annual contributions of as much as $70,000 in 2025, and up to $72,000 in 2026.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026simple IRA For 2026, the SIMPLE IRA contribution limit rises to $17,000, with a $4,000 catch-up for those 50 and over, totaling $21,000.