The Right Price for Investing Advice

We help you navigate the bewildering world of financial advisers.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

On the TV game show The Price is Right, contestants try to guess the correct price of an everyday item. Players whose estimates are closest to the right price go on to compete for valuable prizes. It’s harder than it looks.

The challenge would be even greater if the contest centered on the price of investment advice. You might guess 0.30% of assets for a digital investment plan with a robo adviser, or $2,000 for one year with a certified financial planner. How about $900 for an investment-allocation strategy to implement on your own? A fee based on assets for ongoing portfolio supervision with a money manager might be 0.50%, 0.75% or 1.0%.

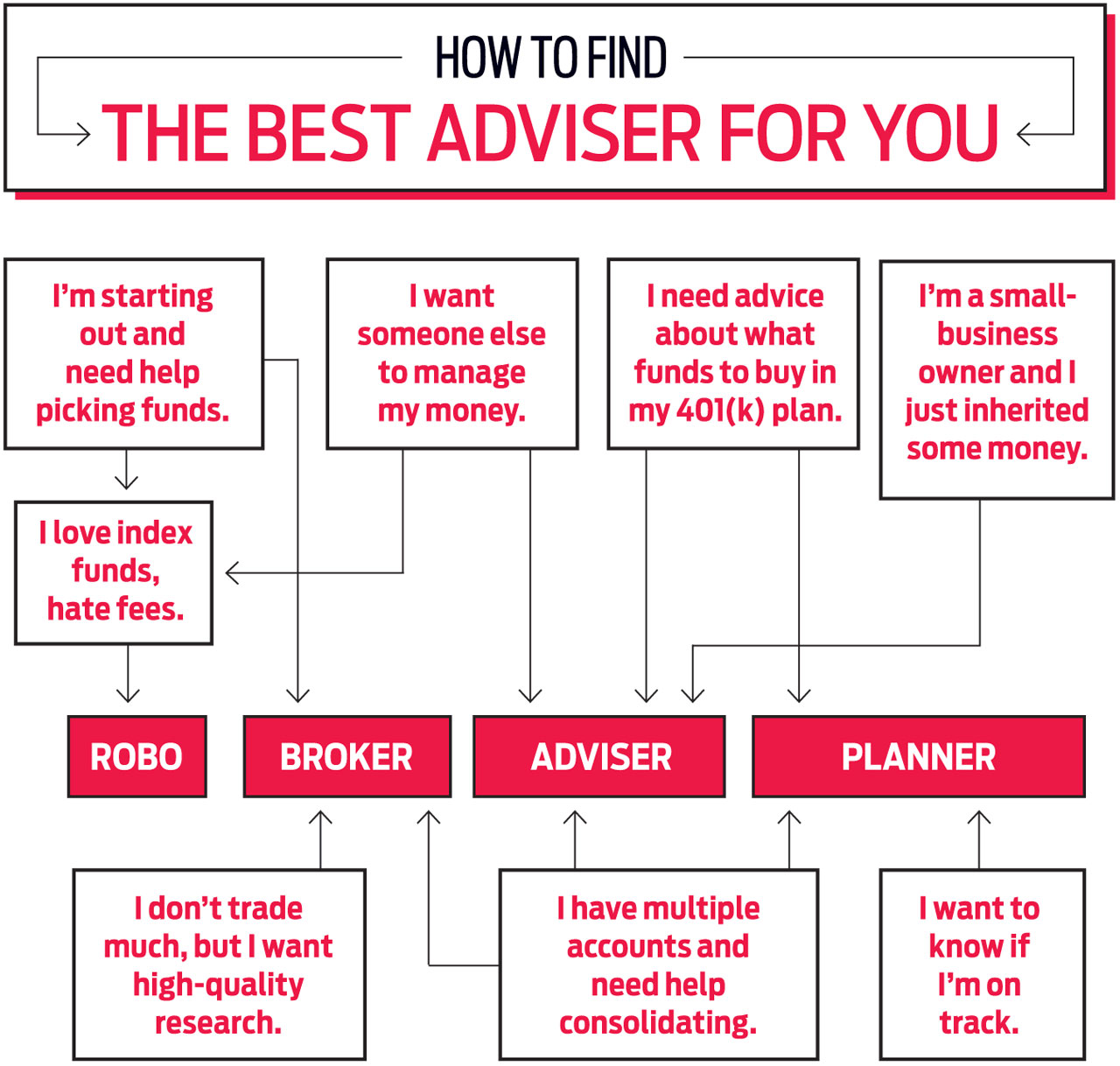

Turns out, there’s no single right answer because of the many kinds of advisory services available; there’s an adviser for almost everyone at nearly any price point. It’s nice to have options, but that can make it hard to choose. And what’s the right price? The key is to figure out your needs and find the adviser who best meets them. We’ll help you do that in this story, and give you an idea of what you should pay.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

The motley mix of advisory fees and providers points to shifts under way in the financial advice industry. Intense competition from robo advisers, which use computer algorithms to offer portfolio management at bargain prices, has been pushing down fees for years. And the U.S. Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, which took effect in June, is nudging advisers to be more transparent about charges. “The industry is moving away from fees for products, toward fee-for-service planning,” says Michael Kitces, a certified financial planner at Pinnacle Advisory Group, in Columbia, Md.

That’s all the more reason to pay only for what you need. Whether you just need advice about your investment portfolio or want help with financial issues beyond investing (or both), defining what services you need will help guide you to the right kind of adviser. These days, there are generally four types: robos, brokers, investment advisers and financial planners, in order of the breadth of services offered. There is crossover among all groups, and many financial professionals hold multiple credentials. Some firms—Charles Schwab and Fidelity Investments, for instance—offer access to all four types of advice. But typically, what—and how—you’ll pay varies by adviser.

For each type of adviser, we list the range of fees you should expect, what you’ll get for your money and what kind of customer the adviser is best suited for.

Robo advisers

Who they are:

Robos are virtual advisers. Answer a few questions online, and computer programs match you with an appropriate, diversified portfolio of low-fee exchange-traded funds tailored to your time horizon and tolerance for risk. The “robots” monitor and rebalance your investments in tax-efficient ways throughout the year, and you never have to talk to a human being. You’ll find robos at dozens of firms, such as Betterment and Wealthfront, as well as discount brokers such as Schwab, TD Ameritrade and E*Trade. Somewhere along the way, many people who use robo advisers yearned for a bit of human interaction. Some firms, such as Personal Capital and Vanguard, were already offering access to a certified financial planner or investment adviser in addition to their digital service. Now others, including Betterment and Schwab, offer access to a human, too.

What they offer:

Robos deliver investment advice in a few mouse clicks. Robo-only services won’t give advice on your 401(k) plan, how to save more for retirement or how to afford college. But hybrid, robo–human services can provide some assistance. At most hybrids, when you need to talk to an adviser, you get the next available person on the phone line. One exception is Personal Capital, where you work with a dedicated adviser.

The fees:

The newfangled services charge clients the old-fashioned way—a percentage of assets under management. The typical robo rate hovers around 0.25% per year, but it can go as high as 0.50%. In most cases, that doesn’t include the expense ratios of underlying holdings. Hybrid services tend to cost a little more: between 0.30% and 0.91% of assets per year.

Best for:

Robos appeal to investors who are looking only for portfolio advice and who are happy with index funds. Robos initially appealed to investors with small accounts, but many firms now have clients with seven-figure portfolios.

Brokers

Who they are:

These professionals work for broker-dealers—firms in the business of buying and selling securities (stocks, bonds, mutual funds and other investment products) for customers. We’re talking Schwab, Fidelity, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Raymond James Financial and the like. Some banks also have broker-dealer businesses, such as Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase. Depending on the firm, brokers are also called registered representatives, financial consultants, stockbrokers, investment consultants or financial advisers.

What they offer:

Ongoing management of your portfolio, shifting your money among assets over time to meet your goals or in response to market moves. With a dedicated adviser, you’ll be able to call anytime you have a question. And clients who have deep pockets can generally get access to more-sophisticated investments, such as private equity, real estate and hedge funds. In addition, many investment advisers offer advice on other financial issues, including insurance and estate planning. Investment advisers are required by law to put your interests ahead of theirs.

The fees:

Advisory fees are usually charged based on assets under management, and the bigger your account, the lower the rate you’ll pay. The typical fee, says Rhoades, is about 1%, though some charge as much as 2% per year and others charge less. At bigger banks and trusts that provide services such as succession planning for small-business owners, fees go up to 3%, says Wei Ke, an analyst with consulting firm Simon-Kucher & Partners. Very high-net-worth clients can often negotiate advisory fees, he adds.

Best for:

Those who want to build a relationship with an active manager of their portfolio. At regional banks, planning, goal-setting or “get me on the right track” help is available, too. At bigger trust firms, the white-glove service includes estate planning, charitable-giving advice and hand-holding for all aspects of your financial life.

Financial planners

Who they are:

Anyone can claim the title “financial planner,” so look for one who has been credentialed by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards. Planners with the CFP designation are required to put their clients’ interests ahead of their own. Many are also registered investment advisers.

What they offer:

Planners can give you advice on investments, and some may offer to manage your portfolio, but they also work with clients to develop a long-term financial plan. That can include strategies for buying a car or a house, how much life insurance to buy, and how to save for retirement and college at the same time. “It’s life coaching,” says Sheryl Garrett, who founded the Garrett Planning Network, a nationwide group of planners who charge by the hour. It’s also about having an adviser always on hand for help with financial questions. “Clients can call anytime,” says Jeremy Brenn, a Collegeville, Pa., certified financial planner.

The fees:

Most CFPs are fee-only and don’t earn commissions. Some charge by the hour, typically between $200 and $400, depending on where you live and the complexity of your finances. Or you might pay a one-time fee for a single project—a budget, for example, or an asset-allocation plan. Other planners charge a fixed annual fee—often called a retainer or subscription—paid monthly or quarterly. Planners working on retainer typically cost between $3,500 and $7,500 per year, depending on the client’s financial situation and needs, according to SEI Advisor Network, an advisory group based in Oaks, Pa. The going rate for planners who charge a percentage based on assets is roughly 1%, but it may be higher or lower depending on the firm and how much money you have.

Sheila Padden, a CFP in Chicago, charges between $2,000 and $20,000 a year. Her $2,000 clients are typically professionals with student loans and about $100,000 in net worth; her $20,000 clients may have $5 million or more and need estate-planning help. Fees are calculated based on multiple factors, including income, net worth and the complexity of a client’s finances.

Best for:

Investors who need financial guidance beyond investing, on everything from budgeting help and debt management to when to start drawing Social Security. For help with a single issue—say, sorting out pension payment options—find a planner who charges by the hour. The catch with an hourly planner, however, is that you execute strategies on your own. If you want someone to do the work for you, or you have more complex needs, build a long-term relationship with a planner. In that case, a retainer model or a fee based on assets under management is more appropriate.

Wherever you go for advice, the right price may boil down to whether you want the lowest cost or better service and more attention. Rapport counts, too—and it’s difficult to put a price on that.

Ask the right questions

Finding the right adviser can feel a little like dating. You’re looking for that magic blend of mutual interests and rapport. And of course, there’s always the small matter of his or her credentials.

A proper interview process can help you address those issues. There are “15 to 20 questions you need to ask,” says Ron Rhoades, a certified financial planner. Checking to see that an adviser has a blemish-free record is a vital step and should be done before you meet. Go to Finra’s BrokerCheck website, www.finra.org/brokercheck. For advisers, search by firm name at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov for disciplinary information.

The North American Securities Administrators Association, which is made up of state securities regulators and works to protect investors, has a list of seven questions you should ask yourself before the interview, and nine you should pose to the adviser. Among the more important questions: Are you required by law to always act in my best interests? Will you put that commitment in writing? How do you charge for your services? Do you receive compensation from other sources if you recommend that I buy a particular investment product? Will you break out all fees and commissions? “Have the adviser write out all of the fees in contract form or on a piece of paper,” says Sheryl Garrett, a certified financial planner and founder of the Garrett Planning Network.

Professional associations can help with the hunt, says Rhoades. Find a fee-only investment adviser through the Alliance of Comprehensive Planners, or the National Association of Personal Financial Advisers. Most of the advisers associated with these groups are certified financial planners and offer all-encompassing financial planning. But you can hire them just to help you with your portfolio. Ask for examples of how the planner or adviser has changed clients’ lives. Make sure you feel comfortable with his or her investing philosophy and strategy.

Finally, plan to meet with at least three (and up to five) advisers. Many advisers offer a free get-acquainted meeting. “People should take advantage of that,” says Garrett. Face-to-face get-togethers help, of course, but younger investors may find a video chat sufficient. And don’t hire someone at the first meeting. “Don’t make a decision while you are emotional about the person you’re meeting with or the money issues you’re confronted with,” says Rhoades. Instead, take notes during the interview and review them a week later. If you have more questions, set up a second meeting. “This is a big decision,” he says, so take your time.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Nellie joined Kiplinger in August 2011 after a seven-year stint in Hong Kong. There, she worked for the Wall Street Journal Asia, where as lifestyle editor, she launched and edited Scene Asia, an online guide to food, wine, entertainment and the arts in Asia. Prior to that, she was an editor at Weekend Journal, the Friday lifestyle section of the Wall Street Journal Asia. Kiplinger isn't Nellie's first foray into personal finance: She has also worked at SmartMoney (rising from fact-checker to senior writer), and she was a senior editor at Money.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayAnother worrying bout of late-session weakness couldn't take down the main equity indexes on Wednesday.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't Need

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't NeedFinancial Planning If you're paying for these types of insurance, you might be wasting your money. Here's what you need to know.

-

Money for Your Kids? Three Ways Trump's ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ Impacts Your Child's Finances

Money for Your Kids? Three Ways Trump's ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ Impacts Your Child's FinancesTax Tips The Trump tax bill could help your child with future education and homebuying costs. Here’s how.

-

Key 2025 Tax Changes for Parents in Trump's Megabill

Key 2025 Tax Changes for Parents in Trump's MegabillTax Changes Are you a parent? The so-called ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ (OBBB) impacts several key tax incentives that can affect your family this year and beyond.

-

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online Bargains

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online BargainsFeature Amazon Resale products may have some imperfections, but that often leads to wildly discounted prices.

-

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should Know

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should KnowMedicare Part A and Part B leave gaps in your healthcare coverage. But Medicare Advantage has problems, too.

-

QCD Limit, Rules and How to Lower Your 2026 Taxable Income

QCD Limit, Rules and How to Lower Your 2026 Taxable IncomeTax Breaks A QCD can reduce your tax bill in retirement while meeting charitable giving goals. Here’s how.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnb

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnbreal estate Here's what you should know before listing your home on Airbnb.