Middle-Class Spenders Will Lead Global Growth

Wealthier overseas consumers spell opportunity for American vendors who can take advantage.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

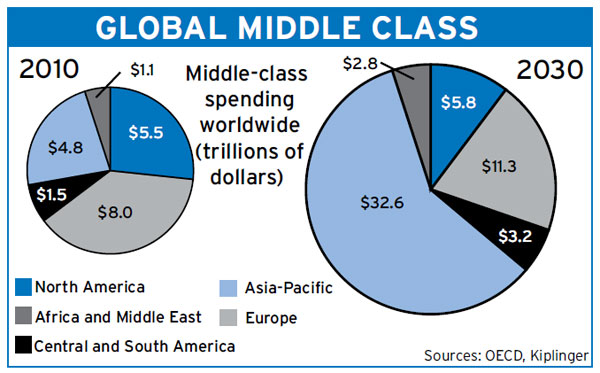

Here's one reason to be optimistic about the long-term potential of the global economy: the emergence of a global middle class. About 1.8 billion strong now, the global middle class will number close to 5 billion consumers by 2030, according to estimates from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Broadly defined as consumers with enough income for food, clothing and shelter basics plus discretionary purchases, this group will spend about $56 trillion a year come 2030, nearly three times as much as they shell out today. These consumers will insist on a higher standard of living, with meatier diets, bigger houses and better hygiene. And they'll clamor for a wide range of consumer goods -- from air conditioners and electronics to cosmetics and organic foods.

Opportunities abound not just for consumer goods, but also for providing services for the growing middle class abroad. Insurance, consulting, financial, medical, engineering and architectural services will be in demand as the quality of life increases. That'll be a boon for U.S. businesses. Services already make up about 30% of U.S. exports and the share will continue to increase in coming years. Growth of the middle class in emerging economies around the world will also give a big boost to U.S. tourism and foreign demand for an American education. International travel by the Chinese alone will grow 17% a year over the next decade. U.S. hotel chains, such as Starwood, Hilton and Marriott, intend to take full advantage of the trend, putting in place programs to reach the growing number of Asian tourists.

For many U.S. businesses, recognizing and acting on this demographic trend will be critical, as long-term economic growth in the mature domestic market flattens out. Americans currently account for 12% of the middle-class population and about one-fifth of its spending. By 2030, U.S. consumers will be just 4% of the middle class worldwide and account for 8% of its spending. Meanwhile, Asia's middle class will explode to make up 66% of the group worldwide and claim 59% of middle-class purchases in 2030. Moreover, despite this year's uninspiring 3.4% gain for the world economy, the pace of gains in Asian, Latin American and African economies still outpace that of the U.S. and most of Europe, now suffering through a recession.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

The shift in the world market spells challenges, too, of course. Reaching customers in different cultures typically requires different strategies, marketing, and in some cases, even different packaging and ingredients. The selection of Kraft's Nabisco Oreos, for example, varies widely by market. There are green tea Oreos in China, a chocolate and peanut variety in Indonesia, and banana and dulce de leche Oreos in Argentina. The company's ability and willingness to adapt its products to local market preferences have helped Nabisco grow the Oreo brand abroad. Emerging markets will account for about half of Oreo sales this year.

Companies will also have to find ways to cut the costs and prices of products made for the U.S. and other developed nations. What's middle class in the U.S. is far above what is middle class in Asia or Africa. In emerging markets, the percentage of truly discretionary income is dramatically lower. In China and India, for example, about 40% of average household income is spent on food and transportation, compared with 25% in the U.S. So much of what is offered elsewhere may be lower-end products than those sold here. When beer manufacturer SABMiller, for example, found it couldn't economically sell its standard barley-based beer to Africa's new middle-class consumers, the company retooled its factories to use cheaper, locally sourced ingredients, such as cassava, to produce a beer at a price African consumers could afford.

The race to reach this mass of new middle-class customers is already under way. American companies have the advantage of brand names known worldwide, but local manufacturers often have a logistical edge. In China, India and elsewhere, they're battling for turf. Chinese beverage maker Hangzhou Wahaha became a $5.2-billion company in trying to stave off Coca-Cola and Pepsi. It benefited from increased consumer demand for soft drinks. Nevertheless, Coca-Cola will double its volume by 2020 with increased sales in emerging markets.

Transitioning to a global market isn't easy. Brand building and customer loyalty takes time. Home Depot, for one, shuttered five of its initial 10 stores in China as it searched for its niche in the marketplace. But a global reach will pay off for most companies as middle-class spending in emerging markets continues its meteoric rise.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Hiding the Truth From Your Financial Adviser Can Cost You

Hiding the Truth From Your Financial Adviser Can Cost YouHiding assets or debt from a financial adviser damages the relationship as well as your finances. If you're not being fully transparent, it's time to ask why.

-

How to Manage a Disagreement With Your Financial Adviser

How to Manage a Disagreement With Your Financial AdviserKnowing how to deal with a disagreement can improve both your finances and your relationship with your planner.

-

5 Actions to Set Up Your Business With Your Exit in Mind

5 Actions to Set Up Your Business With Your Exit in MindWhen you're starting a business, it may seem counterintuitive to begin with exit planning. But preparing will put you on a more secure footing in the long run.

-

Farmers Brace for Another Rough Year

Farmers Brace for Another Rough YearThe Kiplinger Letter The agriculture sector has been plagued by low commodity prices and is facing an uncertain trade outlook.

-

Trump Reshapes Foreign Policy

Trump Reshapes Foreign PolicyThe Kiplinger Letter The President starts the new year by putting allies and adversaries on notice.

-

Congress Set for Busy Winter

Congress Set for Busy WinterThe Kiplinger Letter The Letter editors review the bills Congress will decide on this year. The government funding bill is paramount, but other issues vie for lawmakers’ attention.

-

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026The Kiplinger Letter Here are some of the biggest events and trends in economics, politics and tech that will shape the new year.

-

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026The Kiplinger Letter Economic growth across the globe will be highly uneven, with some major economies accelerating while others hit the brakes.

-

Amid Mounting Uncertainty: Five Forecasts About AI

Amid Mounting Uncertainty: Five Forecasts About AIThe Kiplinger Letter With the risk of overspending on AI data centers hotly debated, here are some forecasts about AI that we can make with some confidence.

-

Worried About an AI Bubble? Here’s What You Need to Know

Worried About an AI Bubble? Here’s What You Need to KnowThe Kiplinger Letter Though AI is a transformative technology, it’s worth paying attention to the rising economic and financial risks. Here’s some guidance to navigate AI’s future.

-

Will AI Videos Disrupt Social Media?

Will AI Videos Disrupt Social Media?The Kiplinger Letter With the introduction of OpenAI’s new AI social media app, Sora, the internet is about to be flooded with startling AI-generated videos.