As Drought Takes a Toll, Water Prices Will Rise

Conservation and technological advances will help utilities meet needs, but at a cost.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

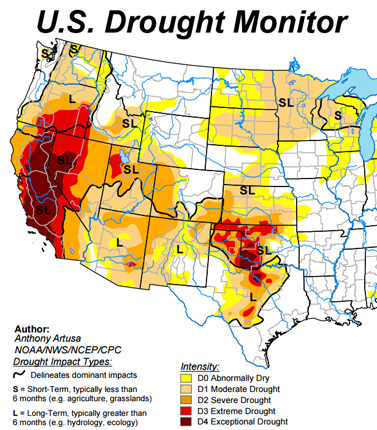

By now, you’ve no doubt read all about California’s historic drought, which is withering farmland and sparking emergency water rationing. But unless you live there, you might not realize that much of the American West is nearly as parched as the Golden State. Moderate to severe drought sprawls across the desert Southwest, the Southern Plains from Texas to Kansas, and much of the normally wet Pacific Northwest.

Technological solutions could go a long way toward relieving drought in many areas. Graywater recycling systems, for instance, capture soapy water from shower and sink drains and clean it enough to use for flushing toilets or watering lawns. Systems large enough for a modest office building can cost $50,000 to $100,000, but the resulting water savings mean the buyer can break even on the investment in about five years. Graywater setups figure to gain in popularity wherever outdoor watering is restricted because of drought.

Graywater helps, but some drought-stricken communities will likely have to turn to more extreme forms of recycling. Two towns in Texas – Wichita Falls and Big Spring – opted for a new type of water reclamation that is likely to pop up across the arid West in coming years: direct potable reuse (DPR).

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

In essence, explains University of Texas civil engineering professor Desmond Lawler, DPR treats and filters municipal wastewater until it is clean enough to go directly back into a town’s drinking water supply. Residents were naturally skeptical, but the DPR process is so effective, says Lawler, that it “removes practically every molecule that isn’t water.” In fact, the resulting water is so clean that it is essentially tasteless, and therefore is mixed with regular freshwater to supply the minerals that “flavor” normal tap water.

While promising, such high-tech solutions can go only so far in freeing up new water sources. Ultimately, drought-stricken communities will rely heavily on an old-fashioned fix: conservation. California has ordered emergency water cuts, and other dry regions are also looking to cut down on water usage where they can. In Oklahoma, for instance, the state’s water resources board is studying ways to encourage water saving, says spokesman Cole Perryman. That includes incentives for municipal water agencies to pinpoint and fix leaking pipes and for farmers to switch to no-till planting, which helps soil hold more water.

In the Southwest, the federal government is offering funds to states along the Colorado River that devise conservation plans to reduce the amount of water being withdrawn from that vital water source. Lake Mead, a crucial reservoir along the Colorado, is nearing a critically low level because of the recent drought, so finding ways to use less of its dwindling water is a high priority for Uncle Sam.

Saving water during dry periods sounds sensible enough, but it does come with a significant catch. The utilities that provide most Americans’ drinking water and sewer service are facing major bills to repair or replace the nation’s aging water mains and other infrastructure. However, the trend toward conservation means less demand for the one basic product that water utilities sell.

Alan Roberson, director of federal relations at the American Water Works Association, says those two trends put water agencies in a bind. Aside from variations in the amount of electricity they consume and the amount of chemicals they buy to treat their water, utilities’ costs of operation are largely fixed. They have to pay to build or maintain the pipes and water treatment plants, even if customers are buying less water. Declining water sales mean lower revenue, even when infrastructure costs are rising.

That means that many water agencies will likely have to raise their rates to compensate for falling sales. And AWWA’s Roberson says many are “taking a hard look” at tacking on fixed monthly charges to water bills. More use of tiered pricing, with escalating rates for water usage above a certain threshold, is also a good bet. Utilities realize that customers don’t exactly welcome such pricing plans, Roberson says. But with so much of the nation’s water infrastructure in need of costly upgrades or replacement, finding sufficient revenue is critical.

So consumers should expect to pay more on their water bills over time, even if they are using less to cope with drought conditions. Conservation does pay off during dry spells, just not necessarily in the financial sense.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Jim joined Kiplinger in December 2010, covering energy and commodities markets, autos, environment and sports business for The Kiplinger Letter. He is now the managing editor of The Kiplinger Letter and The Kiplinger Tax Letter. He also frequently appears on radio and podcasts to discuss the outlook for gasoline prices and new car technologies. Prior to joining Kiplinger, he covered federal grant funding and congressional appropriations for Thompson Publishing Group, writing for a range of print and online publications. He holds a BA in history from the University of Rochester.

-

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Leads a Rocky Risk-On Rally: Stock Market TodayAnother worrying bout of late-session weakness couldn't take down the main equity indexes on Wednesday.

-

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"

Quiz: Do You Know How to Avoid the "Medigap Trap?"Quiz Test your basic knowledge of the "Medigap Trap" in our quick quiz.

-

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter Investing

5 Top Tax-Efficient Mutual Funds for Smarter InvestingMutual funds are many things, but "tax-friendly" usually isn't one of them. These are the exceptions.

-

Trump Reshapes Foreign Policy

Trump Reshapes Foreign PolicyThe Kiplinger Letter The President starts the new year by putting allies and adversaries on notice.

-

Congress Set for Busy Winter

Congress Set for Busy WinterThe Kiplinger Letter The Letter editors review the bills Congress will decide on this year. The government funding bill is paramount, but other issues vie for lawmakers’ attention.

-

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026The Kiplinger Letter Here are some of the biggest events and trends in economics, politics and tech that will shape the new year.

-

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026The Kiplinger Letter Economic growth across the globe will be highly uneven, with some major economies accelerating while others hit the brakes.

-

Amid Mounting Uncertainty: Five Forecasts About AI

Amid Mounting Uncertainty: Five Forecasts About AIThe Kiplinger Letter With the risk of overspending on AI data centers hotly debated, here are some forecasts about AI that we can make with some confidence.

-

Worried About an AI Bubble? Here’s What You Need to Know

Worried About an AI Bubble? Here’s What You Need to KnowThe Kiplinger Letter Though AI is a transformative technology, it’s worth paying attention to the rising economic and financial risks. Here’s some guidance to navigate AI’s future.

-

Will AI Videos Disrupt Social Media?

Will AI Videos Disrupt Social Media?The Kiplinger Letter With the introduction of OpenAI’s new AI social media app, Sora, the internet is about to be flooded with startling AI-generated videos.

-

What Services Are Open During the Government Shutdown?

What Services Are Open During the Government Shutdown?The Kiplinger Letter As the shutdown drags on, many basic federal services will increasingly be affected.