How to Prepare Your Portfolio for the Worst

Buy-and-hold investors are bound for trouble; you can't rely on rising stocks and bonds to deliver positive returns over the next 10 to 15 years.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Over long periods of time, the stock market goes up. How does one define long as it relates to time when considering stock market returns? If we accept the Internal Revenue Service's definition of long-term, it would mean a year and a day, as that is how long investors must hold a security to get long-term capital-gains tax treatment. But advisers would tell you that one year is a short time, so short in fact that an investor shouldn't evaluate a manager's performance on that basis. The same could be said for two-, three- or even five-year time periods. Perhaps we can agree that ten years is a long time. That's a long time to be in a job you hate, a bad marriage or the pen.

However, when buy-and-hold-only proponents make their case, they often lead with the statistic that the market has averaged about 10% a year over the last 85 years. If 10 years, or even 20 years, is a long time, how much weight should be put on a statistic that is based on 85 years of data? I would say, "Some."

Since 1920, there have been 203 rolling 10-year time periods that have had negative returns. There have been 67 rolling 20-year time periods that have had negative returns.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

No one old enough to read these words has an investment time frame of 85 years. In fact, few people old enough to have an interest in these words have more than 20 years. Even if you're going to live to 100, you can't endure 20 years of flat to negative investment returns when you're 50 years old, for example.

In the next 10 to 15 years, simple diversification of assets likely won't be enough to manage portfolio risk for investors.

Success will be dependent on diversifying sources of risk and return.

While this may not be the time to sell all your long-term holdings, it is definitely the time to understand two things: 1) your tolerance for downside risk; and 2) how that matches up with your investment holdings.

Now is the time to get your investment portfolio in shape for the next several years.

To do that, investors must employ tactical strategies that have a mechanism for reducing exposure to risk assets. A quality long-short manager and an allocation to managed futures can help in that regard. But, in my opinion, the obligatory 5% to 10% allocation to so-called alternative investments (such as managed futures and long-short equities with no long bias) will still be insufficient. Investors need a meaningful percentage (25% or more) of their capital invested in strategies that can go to cash as market trends deteriorate.

Investors can't rely on Wall Street to tell them this hard truth.

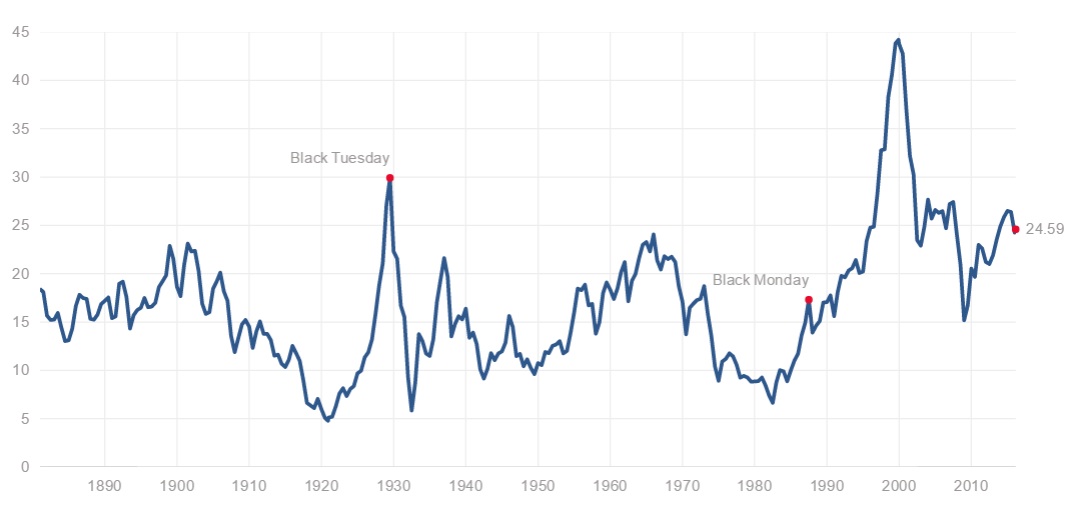

The chart below shows the cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio since the 1880s. Also known as the Shiller P/E, this measurement of value was devised by Yale finance professor Robert Shiller as a way of normalizing earnings.

The current multiple is 24.59. The average is 16.65.

Before the market crash in 1929, the Shiller P/E was 30. Then, the Dow Jones industrial average dropped 89% over the next several years. Likewise, the P/E multiple fell to about 6.

From 1932 to 1937, the Dow went up 260%. Again, the P/E went higher, to the low 20s.

The next five years were volatile—some very nice years before hitting a post-depression bottom in April 1942. You can see the bottom in 1942 and again in 1950. (It's worth noting that as late as August 1953, the Dow was still more than 44% below its peak 24 years earlier.)

Prior to the bear market that began in the late 1960s, the multiple was 23. In 1982, it bottomed in the mid-single digits, setting up an 18-year bull market run.

By December 1999, the P/E multiple hit 44. Since then, the Dow has dropped about 50% two different times. At the conclusion of the most recent big decline, in March 2009, the P/E multiple wasn't in the single digits or even close to it. That market bottom coincided with a low P/E of about 15 (only slightly below the historic average). Why?

In each of the previous five market bottoms, the P/E ratio went below 10 and below 5 once. Why was this time different?

The glaring difference between each of those bottoms and the one in 2009 is the presence of quantitative easing (QE). The Federal Reserve has pumped $3.5 trillion dollars into the economy since the financial crisis began. And that doesn't include the QE policies of other central banks around the world.

One must conclude that QE had the effect of propping up asset prices, including stocks and bonds. It acted as a backstop for falling stock market prices more than a few times in the five years immediately following the financial crisis.

Is it likely that the P/E ratio will go to mid-single digits soon? That's unknown. While it is an unknown, it is what is popularly referred to today as a known unknown. That just means that we know (or should know) that it could happen—because it has happened five times before. In fact, we should be surprised if it doesn't happen.

Other current risks: U.S. government debt is 70% higher than it was before the financial crisis. Corporate profit margins are beginning to compress. All the major averages broke support levels in the past several months but have rallied off the bottom in the last week.

None of this makes the risk-return picture look great for buy-and-hold-only investors.

Take the time to understand the risk in your current portfolio and how that relates to your personal tolerance for downside volatility. Then allocate some of your investment capital to strategies that aren't wholly reliant on a rising stock and bond market to deliver returns. If the future unfolds anything like the past has, investors who do this will be very glad they did.

Roger Davis is CEO of Woodridge Wealth Management, LLC. He lives in Los Angeles CA with his wife and two children.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Roger is a wealth manager for successful families and individuals, speaker, and author of Wall Street's Just Not That Into You: An Insider's Guide to Protecting and Growing Wealth (Bibliomotion, 2015). He is CEO of Woodridge Wealth Management, LLC. Prior to its formation, he was a Senior Vice President at UBS Financial Services and was member of the senior advisory council at J.C. Bradford & Co. Davis has worked as a financial advisor since 1992.