Can Rates Go Any Lower?

Rates can go even lower than they are now. In some European and Asian nations, negative yields have prevailed for years.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

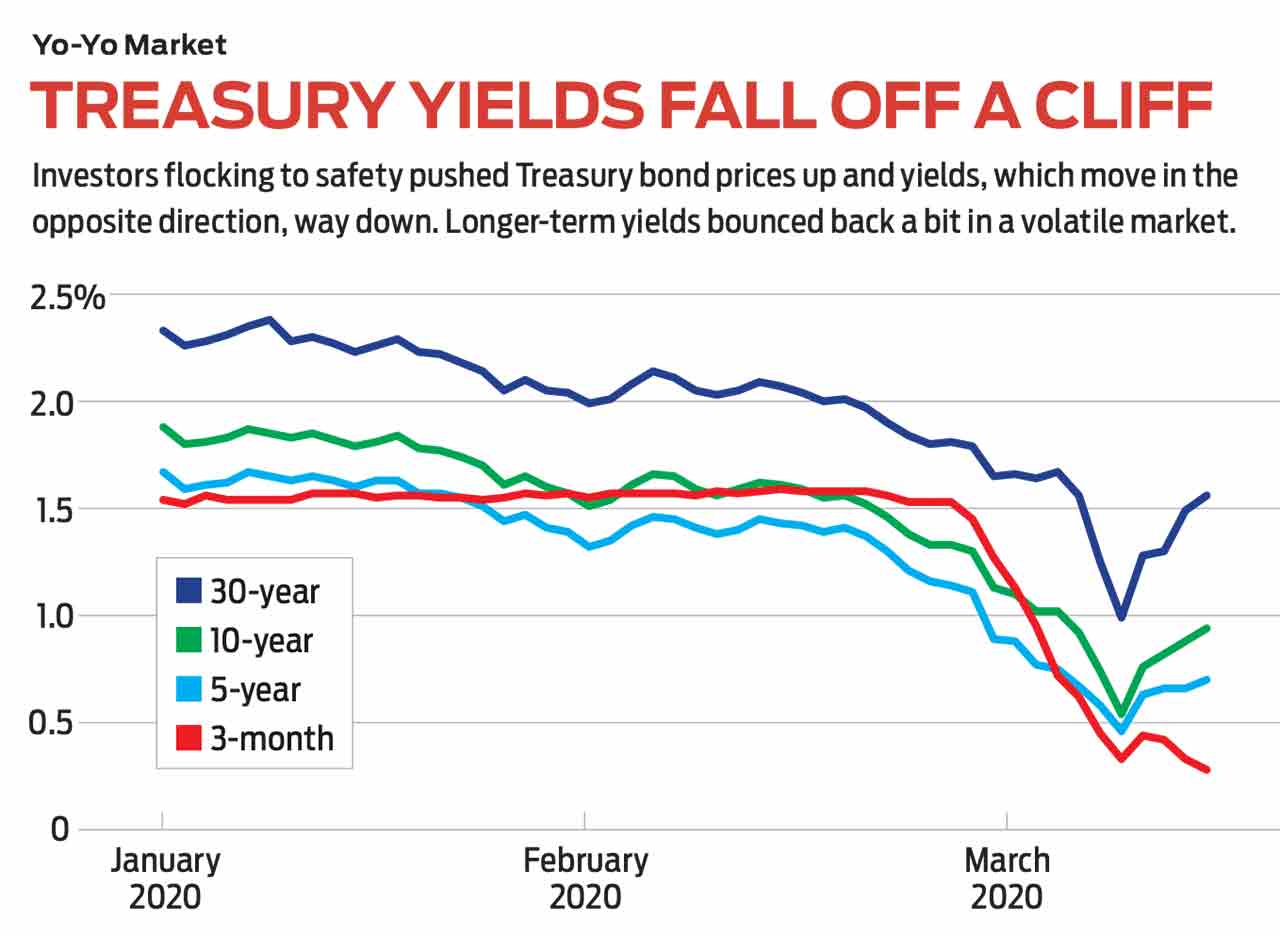

How many times have you heard that interest rates can’t go any lower? And yet they do. Lower and lower and, maybe soon, to zero or below. In fact, ever since 1981, when the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond peaked at 15.2%, government debt has been in a long-term bull market. With the exception of a few upward blips, interest rates have fallen consistently, with the yield on 10-year Treasuries dipping below 1% for the first time ever in early March. That means prices of outstanding bonds, which move in the opposite direction of yields, have been rising.

As a result, bond funds have been superb investments. Vanguard Long-Term Treasury (symbol VUSTX, $15), for example, an exchange-traded fund, has a portfolio of 110 U.S. government bonds with an average maturity of 23 years and charges an expense ratio of only 0.20%. The fund returned 29.0% for the past 12 months and an annual average of 8.0% for the past decade. I still think it’s a good buy. (Prices, returns and other data are as of March 13 unless otherwise noted.)

A bond is an IOU, a promise from a borrower to repay a lender on a certain date, with interest in the meantime. If you wait until maturity, the borrower will return the bond’s face-value amount, but before then you can buy or sell the bond like any other security. Over a bond’s lifetime, its price fluctuates on the open market. One reason for this is credit risk, or changing perceptions of whether the borrower will be able to repay. Such risk, which is critical for corporate and municipal bonds, is absent for U.S. Treasuries, which have never defaulted and probably never will.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Instead, with Treasuries, price is solely determined by the interest rate environment, which itself depends on such factors as the Federal Reserve’s actions on very short-term rates, on inflation, and on the economic and geopolitical climate as a whole.

Like a seesaw. Whatever the catalyst, when rates rise, bond prices fall. Assume you buy a $10,000 Treasury bond with a maturity of 10 years and a coupon (a promised interest rate) of 5%; you collect $500 in interest per year. Now assume that three years later, rates on new 10-year Treasuries fall to 3%. The bond you own that pays $500 a year is worth more compared with the new bond, which pays $300, so the price of your bond increases. Conversely, if rates rise to 7%, your 5% bond becomes less attractive, and its price falls.

Normally, investors who buy and hold bonds do so for the income, but the Vanguard Long-Term Treasury ETF yields a mere 1.5%. The fund’s attractive returns come from the rising value of those bonds as interest rates fall. For example, the Vanguard fund holds a Treasury with a 3.75% coupon that matures in 2043. Recently, when the going rate for debt maturing in about 20 years was 1.4%, the bond was trading at $125.26. In other words, the bond’s 3.75% coupon meant that investors were willing to pay $12,526 on the open market for a bond with a face value of $10,000.

Why have rates fallen so much? Mainly, a sluggish economy. For six decades after World War II, U.S. gross domestic product rose at a brisk pace; then it slowed. The last time annual GDP exceeded 3% was 2005. Inflation—the great fear of bondholders because it depletes the value of what they get at maturity—has remained low. U.S. policy-makers have tried to juice the economy with huge spending programs, large tax cuts and unprecedented reductions in the short-term interest rates controlled by the Federal Reserve. Results have been surprisingly meager.

The economy has been deeply shaken by COVID-19. But even before the pandemic, it lacked the kind of debt demands from businesses and consumers that would normally boost rates in the face of an easy-money policy from the Fed. Government bond rates have plunged as many investors, responding to the coronavirus shock, have fled to safety. Not even during the Great Depression was the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond lower than the 0.5% reached in early March. From 1963 to 2002, the rate never dropped below 4%.

The unknown is always frightening, but there’s no doubt that low rates can be delightful for bond investors, families borrowing to buy houses and businesses looking to expand. As for stockholders: Solid companies are yielding far more than long-term Treasuries—an anomaly. Verizon (VZ, $54) is yielding 4.6%; JPMorgan Chase (JPM, $104), 3.5%; Procter & Gamble (PG, $114), 2.6%; Coca-Cola (KO, $48), 3.4%; and Home Depot (HD, $206), 2.9%. Or how about Microsoft (MSFT, $159)? Its 1.3% yield beats the 10-year Treasury’s yield. Plus, unlike holders of fixed-rate bonds, Microsoft stockholders have been enjoying annual dividend increases every year, from 52 cents in 2013 to $2.04 today.

All six of these stocks are among the 30 components of the Dow Jones industrial average. The very best investment in this environment may well be Diamonds, the nickname for the SPDR Dow Jones Industrial Average ETF (DIA, $232), with an expense ratio of 0.16%.

The mystery of negative rates. Realize that rates can go far below where they are now. In some European and Asian nations, negative yields have prevailed for years. The trend was ignited when the European Central Bank cut its rate below zero as a stimulus to borrowing. In mid March, the yield on 10-year bonds issued by the government of Switzerland was minus 0.51%; Germany, –0.46%; Netherlands, –0.13%; Japan, –0.01%. In effect, the lender is paying the borrower for the favor of taking the lender’s money.

How does this work? You don’t send a check each half-year to the Deutsche Bundesbank. Instead, a bond is said to carry negative interest if the premium—that is, the amount you pay above face value—is greater than the interest you earn over the bond’s life.

These bonds are surprisingly popular. In August, global negative-yielding debt reached a milestone, exceeding $17 trillion, which is the amount that the U.S. Treasury owes to all its public creditors. Why not put your cash under the mattress and get ahead of the game by earning zero? Some bondholders are speculators who are betting they can profit when interest rates get even more negative. Others, including institutions with reserve requirements, keep government bonds on their balance sheets for safety.

The recent regime of super-low interest rates and moderate economic growth has been wonderful for both stocks and bonds. The danger for stocks is when “moderate” becomes “negative”—a growing possibility, and one that’s reflected in recent market volatility. For that same reason, I would be wary of corporate bonds, which add more risk with not much more reward.

Government bonds offer an excellent hedge against a serious slowdown or recession. If you really want to play it safe, then buy a bond fund whose maturities aren’t too extended, such as Fidelity Intermediate Treasury Bond Index (FUAMX), a mutual fund with an average maturity of six years and an expense ratio of just 0.03%. The fund’s returns are lower than those of long-term bond portfolios, but so is its risk.

We are in uncharted territory. We have never seen rates this low, and, although the benefits are obvious, the dangers are fraught. The low rates are trying to tell us something, and it’s not necessarily a pleasant story. Just remember when anyone says that rates can’t go lower … they can.

James K. Glassman chairs Glassman Advisory, a public-affairs consulting firm. He does not write about his clients. His most recent book is Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments in a Time of Turbulence. Of the securities named, he owns Microsoft.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

8 Boring Habits That Will Make You Rich in Retirement

8 Boring Habits That Will Make You Rich in RetirementThese mundane activities won't make you the life of the party, but they will set you up for a rich retirement. Discover the 8 boring habits that build real wealth.

-

QUIZ: Are You Ready To Retire At 55?

QUIZ: Are You Ready To Retire At 55?Quiz Are you in a good position to retire at 55? Find out with this quick quiz.

-

10 Decluttering Books That Can Help You Downsize Without Regret

10 Decluttering Books That Can Help You Downsize Without RegretFrom managing a lifetime of belongings to navigating family dynamics, these expert-backed books offer practical guidance for anyone preparing to downsize.

-

What Tariffs Mean for Your Sector Exposure

What Tariffs Mean for Your Sector ExposureNew, higher and changing tariffs will ripple through the economy and into share prices for many quarters to come.

-

Stock Market Today: S&P 500 Hits High After Verizon Earnings

Stock Market Today: S&P 500 Hits High After Verizon EarningsThe Nasdaq also notched a new high on Monday, while the Dow finished with a marginal loss.

-

What Wall Street's CEOs Are Saying About Trump's Tariffs

What Wall Street's CEOs Are Saying About Trump's TariffsWe're in the thick of earnings season, and corporate America has plenty to say about the Trump administration's trade policy.

-

Verizon Sails to the Top of the Dow After Earnings Beat: What to Know

Verizon Sails to the Top of the Dow After Earnings Beat: What to KnowVerizon stock is one of the best Dow Jones stocks Friday after the telecommunications giant beat estimates for its fourth quarter. Here's what you need to know.

-

Stock Market Today: Stocks Struggle for Direction as Earnings Roll In

Stock Market Today: Stocks Struggle for Direction as Earnings Roll InWhile General Motors stock soared after earnings, GE Aerospace and Verizon slumped.

-

Stock Market Today: Stocks End Mixed Ahead of August Jobs Report

Stock Market Today: Stocks End Mixed Ahead of August Jobs ReportThe main indexes struggled for direction Thursday after data showed the labor market continued to cool.

-

Verizon to Buy Frontier Communications, Hikes Dividend

Verizon to Buy Frontier Communications, Hikes DividendVerizon's purchase of Frontier will significantly expand its fiber footprint across the United States. Here's what you need to know.

-

Stock Market Today: Mega-Cap Tech Rallies to Drag Markets Higher

Stock Market Today: Mega-Cap Tech Rallies to Drag Markets HigherMarkets focused on upcoming earnings from Magnificent 7 stocks rather than chaos in D.C.