How to Navigate Investing in Emerging Markets

Currency woes and runaway inflation in some countries mask long-term opportunities.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

If you’ve been investing in emerging-markets stocks, you probably have a bad case of whiplash. After a rip-roaring run in 2017, the MSCI Emerging Markets index fell 17.7% from its peak in late January 2018 through mid September. “There’s certainly a lot of volatility out there,” says Arjun Jayaraman, a manager of Causeway Emerging Markets fund. “And yes, there will be more.”

That’s no reason to run from emerging-markets stocks, though. In fact, it may be a good time to dip in, especially if your portfolio is out of line with your long-term investment plan. Even a moderately risk-tolerant U.S. investor with a 10-year time horizon should have 30% of his or her stock portfolio in foreign shares, and of that, 6% should be devoted to emerging-markets stocks, says Joe Martel, a portfolio specialist at T. Rowe Price.

But you need to understand the dynamics at play in these far-flung, volatile and, yes, risky markets.Rising interest rates and a stronger dollar are a drag on emerging-markets stocks. The Federal Reserve has hiked rates three times since late 2017, with more to come. That makes U.S. assets more attractive, pulling investments away from emerging markets—money that those countries need to fuel economic growth. “The U.S. threw a stone in the water,” says Philip Lawlor, managing director of global markets research at FTSE Russell. “And the ripples are in emerging markets.”

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

A stronger dollar is a natural outcome of the rise in interest rates. The greenback has gained 7.2% against a basket of foreign currencies since early February. That spells trouble for the many emerging-markets countries that have significant chunks of debt denominated in U.S. dollars. A stronger dollar means they must fork over more of their home currency to buy dollars to pay their debts. Countries that seek new loans face heftier borrowing costs, too. Dollar-denominated debt owed by emerging-markets countries has more than doubled since 2009 and is at a record high.

Tough choices. Emerging nations are in a pickle these days, with a stronger dollar not only pushing emerging-markets currencies lower but also nudging inflation higher. Many countries haven’t implemented the traditional fix—a hike in interest rates to defend their currency—because to do so could crimp economic growth at home. Turkey finally did so in mid September, after the lira had lost nearly half of its value since the start of 2018. The move boosted the currency from its August low, but it is still down 38.6% for the year.

It was just a matter of time before the most vulnerable emerging economies, including Turkey and Argentina, teetered. Turkey has foreign-currency-denominated debt worth 82% of its gross domestic product; Argentina, 54%. Since the start of the year, Turkish stocks have lost 50.4% and Argentine shares have plunged 54.3%.

But not all emerging-markets countries fell into the same debt trap. “Some countries learned their lesson in the Asian currency crisis in the late 1990s,” says Lawlor. China, India, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia and Korea owe foreign-currency-denominated debt that amounts to roughly 30% or less of their GDP, according to BlackRock Investment Institute. The stock markets in those countries are down, too, but not as much; only China and Indonesia are in bear-market territory.To further muddy the waters, an escalating row over tariffs threatens markets and economies all over the world. The U.S. has had trade disputes with six of its top seven export markets. The U.S. has imposed duties on $250 billion of Chinese goods—nearly half the value of all goods that China exported to the U.S. last year. That could be another drag on China’s already slowing economy. Continued slowdown in China, a driver of global growth since the financial crisis, would particularly hurt emerging markets.

Investors should fight the tendency to approach the developing world as a single asset class, says Andrey Kutuzov, a portfolio manager at Wasatch Advisors. “It’s really a collection of different countries with little in common.”

What to do now. Expect continued volatility and possibly more losses. But for investors with five- to 10-year time horizons who can stay the course, this could be a good buying opportunity, says Jim Paulsen, chief investment strategist at the Leuthold Group. Shares in emerging markets trade at 11 times expected earnings for 2019. In the U.S., by contrast, stocks trade at 17 times expected earnings. And though growth has slowed, many emerging economies are still expanding at healthy rates. On average, analysts expect more than 5% GDP growth in emerging countries in each of the next three calendar years, beating the 1.7% to 2.2% annual rate expected for developed countries.The long bull market in U.S. stocks has left investors with a “too U.S.–centric investment mindset,” says Paulsen. If emerging-markets stocks are underrepresented in your portfolio, consider gradually shifting some of the assets tied to your biggest U.S. stock winners to foreign shares. It’s a simple sell-high, buy-low strategy.

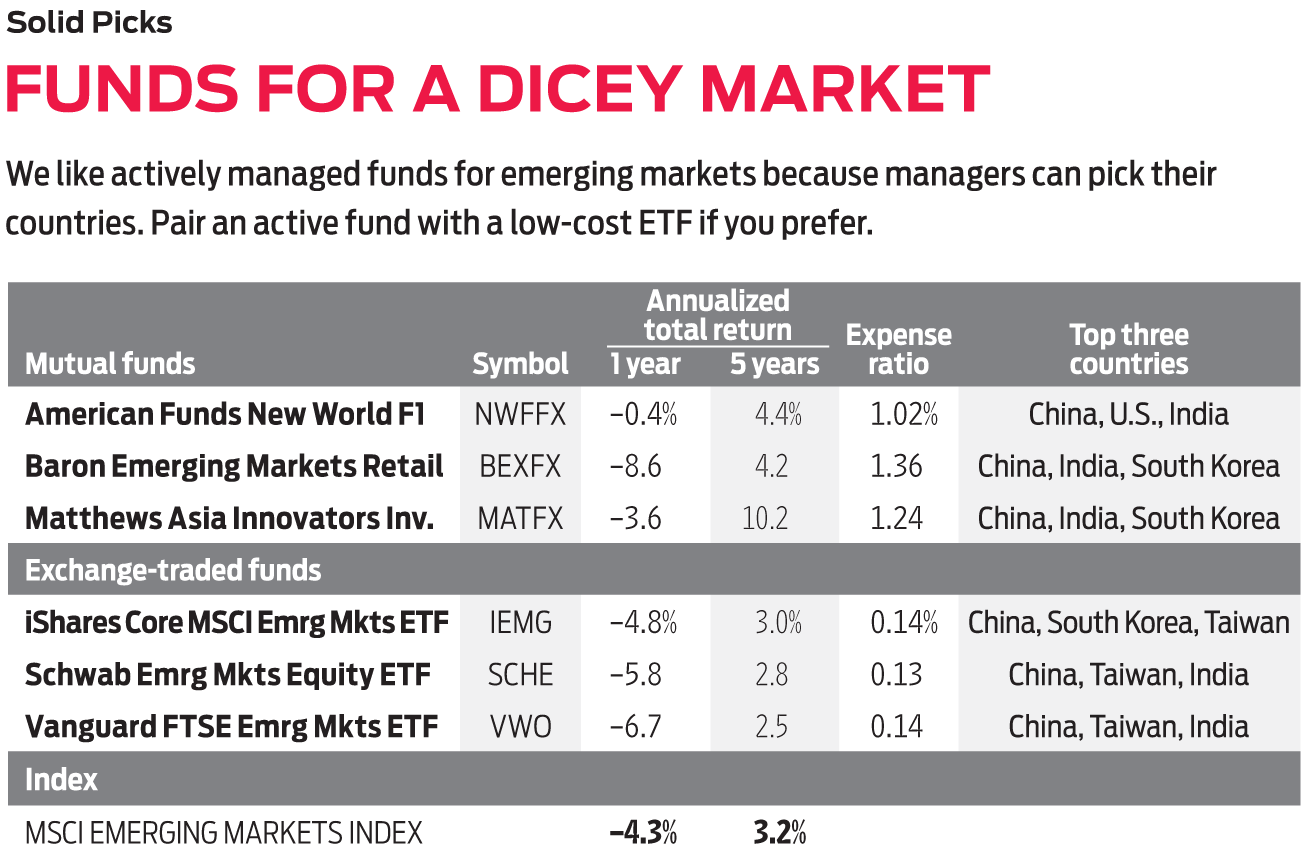

Index fans can choose a low-cost portfolio, such as Schwab Emerging Markets Equity ETF (symbol SCHE, 0.13% expense ratio), iShares Core MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (IEMG, 0.14%) or Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets ETF (VWO, 0.14%). But navigating emerging markets will be tricky in the near term, and if you go the index-fund route, at least pair it with a good actively managed fund. You’ll want a pro who can focus on the better-positioned countries, such as South Korea, Taiwan, India and China, while also snapping up bargains that have been unfairly punished in troubled nations. The funds below are worthy choices.

Baron Emerging Markets (BEXFX)

This fund—a member of the Kiplinger 25, the list of our favorite no-load funds—doesn’t own any stocks in Turkey. Instead, manager Michael Kass has invested more than half of the fund’s assets in China, India and South Korea. At the end of 2017, a good year for emerging-markets stocks, Kass had expected 2018 to be underwhelming and volatile, and it has been—although perhaps more than he had anticipated. But, he says, “We are beginning to see value and opportunity in certain countries, such as Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia and Thailand.” Over the past five years, Kass has outpaced the MSCI EM index by an average of one percentage point per year.

American Funds New World (NWFFX)

This fund is a good choice for investors in search of a way into emerging markets that offers a little less volatility. About half of the fund is invested in emerging-markets stocks; the other half is invested in big developed-country multinationals that have significant sales or assets in emerging markets. “It’s a global approach to investing in emerging markets,” says David Polak, an investment director with the fund. “To cash in on Chinese consumers who are buying luxury goods, you have to invest in European companies. But if you want to invest in the growth of the internet in China, you buy shares in Chinese companies.” The fund’s five-year annualized return of 4.4% beats the MSCI EM index, with more than 25% less volatility.

Matthews Asia Innovators (MATFX)

In our search for good emerging-markets funds, we sought portfolios that held up better than similar funds during downturns and outpaced them during good periods. This fund has one of the best records on those fronts. Lead manager Michael Oh can invest in developed and emerging Asian countries, but most of the fund’s assets—67% currently—are invested in emerging countries. Oh focuses on firms with cutting-edge products or technology, but this isn’t a tech-only fund. Financial services and consumer stocks—two traditionally important emerging-markets sectors—each make up more of the portfolio than tech companies.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Nellie joined Kiplinger in August 2011 after a seven-year stint in Hong Kong. There, she worked for the Wall Street Journal Asia, where as lifestyle editor, she launched and edited Scene Asia, an online guide to food, wine, entertainment and the arts in Asia. Prior to that, she was an editor at Weekend Journal, the Friday lifestyle section of the Wall Street Journal Asia. Kiplinger isn't Nellie's first foray into personal finance: She has also worked at SmartMoney (rising from fact-checker to senior writer), and she was a senior editor at Money.