How to Provide Financial Help to Aging Parents

When it’s time to step in, avoid the stumbling blocks with these strategies.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Mark Kress, 59, of Sterling, Va., first realized his 88-year-old father, Willard, needed help after he saw some bills with past-due balances stacked on his father’s kitchen table. That was completely out of character for Willard, who had a successful career as a certified public accountant.

Initially, Willard didn’t believe he needed help. For most of his adult life, he had managed his investment portfolio and done his own taxes. But over five years, Kress and his four siblings gradually persuaded their father to let them take control of his finances.

It wasn’t a simple task. Willard had multiple bank and investment accounts, and none of them were online. After going through a pile of paperwork, Kress and his siblings managed to consolidate Willard’s bank accounts and arrange for electronic payment of regular bills. Distributions from his retirement savings account are automatically deposited in his bank accounts, along with his Social Security payments and dividends from a brokerage account. Kress’s brother has power of attorney for Willard’s finances and has online access to his bank accounts so he can make sure there’s enough money to pay the bills.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Although the family has now successfully streamlined Willard’s finances, Kress says, it was a long, drawn-out process. “We probably erred in not taking control sooner.”

Numerous studies have shown that our ability to manage complex tasks diminishes as we get older—and for financial tasks, the decline typically starts after age 60. But because the decline is gradual, many seniors don’t realize that they’re having trouble managing money, says Michael Finke, dean of the American College of Financial Services, who has researched cognitive decline’s impact on financial decision-making.

That’s why it’s critical to start talking to your parents while they’re still able to make appropriate decisions, Finke says. “Often, by the time parents have lost their ability to make sound financial choices, they’ve also lost the ability to evaluate who they can and can’t trust.” That makes them vulnerable to bad advice from unscrupulous relatives or financial advisers, he says.

Start the conversation

Knowing that the ability to make good financial decisions starts to diminish when you’re still in your peak earning years can provide an opening for baby boomers to discuss this sensitive topic with their parents. Tell your parents that you have started to discuss your finances and retirement plans with your own children or others you trust.

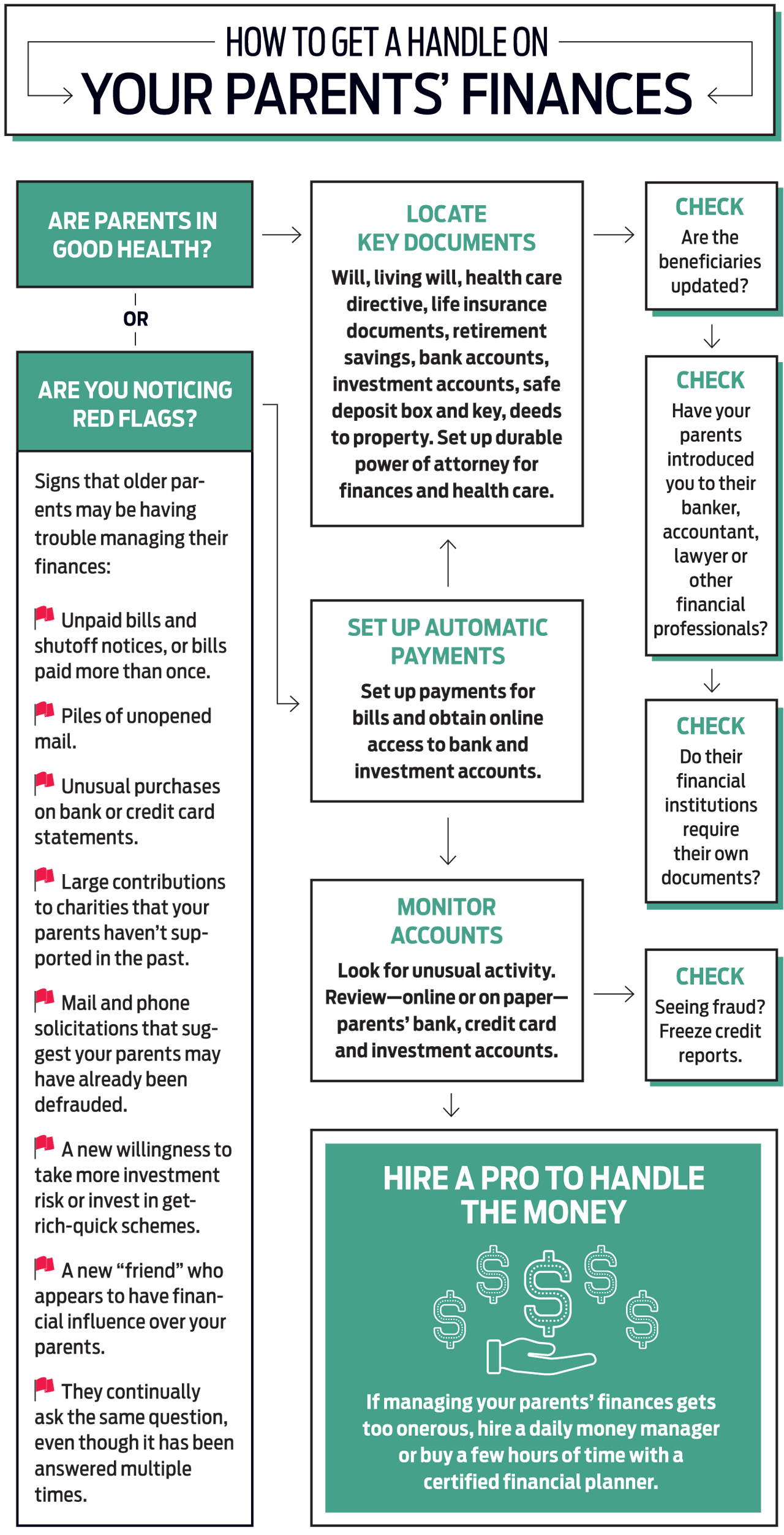

Another effective way to broach the topic of your parents’ finances is to ask them whether they have core estate-planning documents, including powers of attorney for finances and health care, a will and, in some cases, a living trust. You should also ask your parents whether they’ve updated beneficiaries for life insurance policies, retirement savings plans and other types of accounts. If they’re reluctant to share details of their finances, stress that your main concern is to be able to locate these key documents if they become incapacitated or die.

That’s how Charles Rotblut, vice president of the American Association of Individual Investors in Chicago, initiated the conversation with his father-in-law, Les. It helped that Les, a retired NASA employee, had a lifelong interest in finance and enjoyed discussing investment strategies with his son-in-law. About five years ago, Rotblut, now 50, encouraged Les to discuss plans for his estate and his funeral. Rotblut’s wife, Marni, went with her parents to meet with their estate attorney in Texas, where they lived, and Rotblut dialed in. Les also allowed Rotblut to follow him around the house with a notebook so he could write down where various documents were kept.

When Les died in March at age 82, Rotblut had an inventory of his in-laws’ bank and brokerage accounts, along with their sources of retirement income and life insurance. Rotblut also knew where to find their tax returns. Rotblut’s mother-in-law (who asked that we not use her name) has continued to pay the bills—which she did while Les was alive—but her daughter and son-in-law will sometimes sit down with her while she writes the checks. And Rotblut receives monthly statements from his mother-in-law’s bank and has online access to her account. Rotblut also monitors his mother-in-law’s investments and has the power to make changes and withdrawals on her behalf. “It’s very casual,” Rotblut says. “We’re not interfering but very quietly paying attention so we know what’s going on.”

Many seniors are understandably reluctant to allow anyone—including their children—to move money on their behalf. But you may be able to persuade them to let you monitor their financial activities, which can help you identify problems early on. Some investment firms even provide “read only” statements to family members designated by the client.

Thomas Lapp of Philadelphia says his father gave him access to his online accounts so that Lapp could keep an eye out for unusual credit card charges or other potential problems. That was about three years ago. Recently, Lapp’s father gave him permission to manage the accounts. “It was a transition from me being a second pair of eyes and looking over his shoulder to him looking over my shoulder,” Lapp says.

Taking charge

At some point you may need to be more hands-on. Maybe unpaid bills are piling up at your parents’ house, a parent was the victim of fraud, or he or she just no longer wants to deal with bills and taxes.

“Stepping in is one of the hardest things in the world. It’s more than just having a conversation about finances,” says Catherine Collinson, president of the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies. It’s a conversation with a loved one about his or her ability to continue to manage finances.

If you haven’t been heavily involved in your parents’ finances, start by finding out about assets and how they have been spending money. “In some ways, you have to be a detective,” says Hyman Darling, president of the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys.

Review bank and credit card statements for the past six months to learn what bills regularly come in and must be paid, says Matthew Boersen, a certified financial planner with Straight Path Wealth Management in Jenison, Mich., who managed his grandmother’s finances for three years. Look for charges for services that may no longer be used and can be canceled.

Investment and bank statements will give you an idea of your parents’ assets and income. But check your parents’ latest tax return and 1099 forms for any overlooked income sources.

Review insurance policies as well as valuable veterans’ or employer benefits that even your parents may not be aware of, says Paul Tramontozzi, a certified financial planner with KBK Wealth Management, in New York City. Tramontozzi stepped in to manage his parents’ finances about three years ago after his father, a retired language teacher, was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia and his mother was preoccupied with caregiving. He discovered that his father had paid for years for a workplace insurance policy that provided 1,200 hours a year of home aid—a $30,000 annual benefit.

If your parents are like many others, they’ve acquired a variety of bank and investment accounts over the decades. Consolidate them to make oversight easier. Tramontozzi spent months consolidating his parents’ accounts, which revealed another issue. “When you have your investments so fragmented like that, once you put it together, the investment mix doesn’t make sense,” he says. “Ultimately, once you consolidate, there is some type of rebalancing.”

Rather than writing multiple checks every month, set up automatic bill payments for your parents. Make sure you maintain good records of income and expenses, such as medical bills that may be tax-deductible. Careful bookkeeping can also help alleviate any sibling concerns about how you’re managing your parents’ affairs.

Line up the right documents

Taking charge will be much easier if your parents have signed a durable power of attorney, which can give you broad powers or spell out specific actions you’re allowed to take, such as paying bills, selling assets and gaining online access to accounts, says Darling. If you don’t have this document and a parent becomes incapacitated, you will have to go to court to be appointed the guardian or conservator—a process that can take a month or longer and require you to make annual accountings to the court.

Some parents set up a revocable trust, naming themselves as the trustee and the trust as owner of their assets. Among the benefits: A child named as successor trustee can then smoothly transition into managing those assets. Even with this, you will still need a power of attorney to handle assets and financial matters that fall outside the trust, says Leslie Thompson, managing principal at Spectrum Management Group, in Indianapolis.

Many states either require banks and brokerages to honor valid powers of attorney or relieve institutions of liability when they accept the documents. But even in those states, elder lawyers say, it’s not uncommon for financial institutions, particularly large ones, to insist that a family use their power of attorney form.

Banks and financial institutions are wary of the growing number of cases of fraud against seniors—many of them perpetrated by family. “From the bank’s perspective, suddenly they have people they have never met announcing themselves as the new fiduciary, often without the actual customer with them,” says Corey Carlisle, executive director of the ABA Foundation. “If they show up with a durable power of attorney, they can wipe out a person’s account instantly.”

The simplest solution is for you and your parents to visit the financial institutions your parents deal with and see if they will accept your power of attorney or require you to sign theirs. This way, you won’t run into surprises later, and it allows you to establish a relationship with the bank or brokerage.

Help with oversight

In fact, it’s a good idea for your parents to introduce you to all the professionals in their lives, including their accountant, lawyer, financial adviser and bank representative, who can be part of your team that manages your parents’ affairs. Shon Anderson, a certified financial planner in Dayton, encourages adult children of his clients to sit in on a financial planning review so they can get a good picture of their parents’ finances from a third party.

A financial planner can also provide you with tools to help you get organized. Anderson offers his clients a digital filing cabinet for copies of key documents, such as a power of attorney and a living will. Many financial planners also offer software that can consolidate parents’ investments, other assets, debts, account numbers and contact information, says Scott Hughes, a certified financial planner in Herndon, Va.

If your parents don’t have an adviser, stand-alone programs can help with oversight. EverSafe, a monitoring service created with seniors in mind, will scan bank, retirement, investment and credit card accounts as well as credit reports to understand a customer’s normal financial activity. EverSafe then issues alerts to the customer—and any trusted people designated—if it uncovers anything outside the norm, such as unusual spending behavior or missed deposits, says Elizabeth Loewy, a former prosecutor and cofounder of EverSafe. The monthly cost ranges from $7.49 to monitor bank and credit card accounts to $22.99 for credit reports and unlimited accounts.

If fraud is a concern, freeze your parents’ credit reports at each of the three major credit bureaus. This prevents someone from opening credit under a parent’s name because companies can’t view the reports. You can lift the freeze if your parents want to apply for new credit (see I Thwarted ID Thieves). Also, keep your parents up to date on the latest scams targeting seniors.

Although taking control of your parents’ finances is a drastic move, it may be the only way to protect your parents from unscrupulous people who prey on senior citizens. David Houston, a wealth management adviser for Northwestern Mutual in Oklahoma City, learned that lesson after his widowed father was befriended by a 32-year-old woman who had a history of exploiting elderly men. She had previously persuaded an 85-year-old man in his father’s hometown to bequeath her his entire estate, leaving his family with nothing when he died.

Houston was unable to convince his father, who died two years ago, that the woman was up to no good, and she ended up with more than $100,000 from his bank accounts. But Houston did persuade his father to give him control of a living trust that contained commercial real estate and other large family assets. “When he voluntarily stepped down as trustee, he gave us authority to control those,” Houston says. “That’s the only reason we still have them.”

Hiring help

If handling your parents’ finances becomes too much for you—or you want to preserve your parents’ independence while having someone keep an eye on things—consider hiring a daily money manager. This person basically serves as your parents’ assistant, helping to pay bills, manage the mail, negotiate with creditors and even, if necessary, remind a forgetful parent not to give out bank account numbers to strangers over the phone. “A lot of what we’re doing are the kinds of things an adult child would do,” says Leah Nichaman, board president of the American Association of Daily Money Managers, which has about 800 members. Fees range from $60 to $150 an hour, and managers typically meet with clients twice a month.

You can get names of daily money managers in your area at the association’s website or from lawyers, accountants or your local Area Agency on Aging. When interviewing money managers, find out how long they’ve done the job, how they bill, whether they charge for travel time, whether they’re insured and the steps they take to keep your parents’ information confidential, Nichaman says. Ask for names of clients who can tell you what the manager was like to work with.

Ruth Milkman, 58, of Arlington, Va., hired a daily money manager two and a half years ago because her mother, who has Alzheimer’s, was having trouble staying on top of her finances. The daily money manager spends a few hours a week with 86-year-old Marianne Milkman in Washington, D.C., and has helped her with a wide range of tasks, such as paying bills, running errands, reviewing bank and credit card statements for questionable items, and negotiating with the cable TV company. When Marianne lost her wallet, the money manager canceled her credit cards and took her to the department of motor vehicles to get a new ID.

“She is also another set of eyes and ears at noticing how things are going with my mom,” Milkman says. For instance, when her mother went on a new medication, Milkman asked the daily money manager to keep an eye out for any side effects.

The daily money manager provides another important benefit to Milkman, a telecommunications lawyer, and her three siblings. “We all work. We would rather spend our time with our mother on other things than going through her bills.”

Help your adult children help you

Seniors don’t need to share every detail of their finances with their adult children. You should, however, make sure that someone can manage your finances if you become unable to do it yourself. Information you should share with someone you trust includes:

-- Estate-planning documents, including powers of attorney for finances and health care.

-- Location of your safe deposit box (if you have one) and keys.

-- Your Social Security numbers.

-- Birth and marriage certificates.

-- Names and contact information for your financial institutions, including banks, credit unions, brokerage firms and insurance companies.

-- Information about your pension (or pensions), life insurance and annuities.

-- Names and contact information for your financial adviser and tax preparer.

-- Deeds to property and cemetery plots.

-- Vehicle titles and registration.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.