PODCAST: Which Documents to Keep, Which to Shred and Which to Scan

A speedy recovery from disaster can depend on your recordkeeping. Kiplinger’s Personal Finance writer Rivan Stinson tells us how to get our papers in order.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Subscribe FREE wherever you listen:

Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Overcast | RSS

Links mentioned in this episode:

- Now You Can Own Bitcoin in 401(k)s. Should You?

- Trading Options for Your 401(k)

- US Department of Labor cautions 401(k) plan fiduciaries to exercise extreme care as they consider cryptocurrencies

- Create a Financial Plan for Natural Disaster

- How to Protect Your Home from Natural Disasters with the Right Insurance

Transcript:

David Muhlbaum: What documents can you throw out, and which must you save, and where do you put them, is a debate as old as, well, writing things down. But technology and natural disasters have thrown in a few new twists.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

We’ll explore the latest on keeping records safe and accessible with Rivan Stinson of Kiplinger’s Personal Finance. Also, you might be able to invest your 401(k) savings in Bitcoin, all coming up in this episode of Your Money’s Worth.

Welcome to Your Money’s Worth. I’m kiplinger.com senior editor, David Muhlbaum, joined by my co-host, Kiplinger senior editor Sandy Block. Sandy, how are you doing, and for chuckles, tell the good people where you are.

Sandy Block: I’m at a state park in West Virginia that has good wifi, and more importantly, a good bar.

David Muhlbaum: And a little room. You have your own little subsidized recording studio in there.

Sandy Block: I’m in the business center, which shockingly on a beautiful spring day, is totally empty. Everybody else is at the bar or the golf course.

David Muhlbaum: Yeah. Well, good. The truth is that we are still recording remotely here, with me and Sandy just waving at each other, and sometimes the guests, through a screen. But we have obtained a new mixing board for our studio at the offices. We are planning a return to recording in the shared human space. Will anyone notice? I don’t know yet. I’m looking forward to recording without worrying about leaf blowers, or one of our dogs barking in the background. Anyway, that’s the future, hopefully the near future. For now, Sandy, a story that absolutely caught my eye this week was the news that it’s going to be possible, at least for some people probably, to invest in Bitcoin in their 401(k).

Sandy Block: That’s right. The 401(k), which is going to be the pension plan for most of us, is messing around a little bit with cryptocurrency. Making matters even more interesting, Fidelity Investments, a giant in the 401(k) area, is the one that is involved in this.

David Muhlbaum: Yeah, it makes it this powerful headline. But splashy as it is, it hasn’t upended the retirement investing world, or 401(k)s. Look, I tend to think of it as like that’s where you invest a portion of your salary in a nice, diversified well-managed range of mutual funds, not Bitcoin, which is speculative. I’m not even arguing about the merits of crypto here. It’s not the time. I’m just saying, look at the trading range of Bitcoin, that’s volatile, that’s speculative.

Sandy Block: That’s right. If you think the stock market is volatile, take a look at Bitcoin.

David Muhlbaum: So, why?

Sandy Block: Well, I think that, certainly among young people, there is a lot of interest in Bitcoin. Fidelity is a business, and it wants to meet its customers needs. It certainly got Fidelity a lot of attention with this announcement. I think the more you hear about Bitcoin, for many people, that’s the only way they can invest is through their 401(k). So, maybe they think this is something that might catch on.

David Muhlbaum: Okay, but let’s sort out for a second who the customers are. Because Fidelity is the plan provider. They’re supposed to provide the platform by which you can invest 401(k) money. They don’t tell you what to do. Those choices of what options you can invest in, that goes to whatever company wants to use Fidelity to administer its 401(k).

Sandy Block: Right, and even then, just because they’re using Fidelity doesn’t mean that they’re going to automatically offer Bitcoin.

David Muhlbaum: It’s a choice for the customers to do that.

Sandy Block: That’s right. The customers, unlike Fidelity, have a fiduciary duty. They are required basically to make sure that the funds, and investments that they offer their workers ... It’s the federal law. It will be interesting. My guess would be that maybe some high tech companies that have a lot of young, crypto minded employees might wade into this. But really the trend in the most recent years is making 401(k)s simpler, not harder. What they found is people don’t like a lot of choices in their 401(k)s. That’s why such a huge amount of money now goes into target funds, where basically you put the money and then sit back and let somebody else manage it for you. A lot of people really do not want to get down and dirty in their 401(k)s. They would rather have someone else do it and not have to worry about it.

David Muhlbaum: At the same time, there is this subset of people who very much do want to trade and fiddle around. There’s the brokerage window, which you’ve written about, the ability to trade stocks in a 401(k). That’s popular?

Sandy Block: It’s not. The number of people who actually use the brokerage window is very small.

David Muhlbaum: Okay, but they care. I guess that’s what I was getting at, they care.

Sandy Block: Yeah. But what the brokerage window does, a large company 401(k) plan might say, "Here are three target funds," an index fund and a growth fund, and maybe offer 10 funds to invest in. Then they’ll also say, "If you would like to invest in more types of things, you can go into the brokerage window." Oftentimes a brokerage window will offer a much broader variety of mutual funds and individual stocks.

Sandy Block: Oftentimes the fees are higher, and as I said, the take up of these has not been that great, but it is a way for a company to say, "If you really want to go a little wild with your 401(k), we will let you in your brokerage window, but we are not selecting these funds for you." When you go into the brokerage window, you do that yourself.

David Muhlbaum: Right. But there is a potential tax advantage here too, for both the stocks, and very much crypto?

Sandy Block: I think one of the advantages of investing in cryptocurrency or Bitcoin in your 401(k) is that taxes on your gains are deferred until you take the money out. What a lot of newbie Bitcoin and cryptocurrency investors don’t realize is, for the purposes of the IRS, they are treated just like any other asset. If you make a lot of money in Bitcoin and sell it, you owe capital gains on that amount. If you trade crypto, if you trade Bitcoin, and it gets real high, and you take some money off the table and reinvest it, well you’re going to owe taxes on that money. The IRS is so concerned about this, that it’s right up there on your 1040, "By the way, if you owned any cryptocurrency and you made money on it, you have to pay up."

David Muhlbaum: Right. But for the 401(k) investor, yes, they won’t be taxed on those gains. On the other hand, they can’t touch them either because it’s a retirement account.

Sandy Block: That’s right, it has to sit there until you retire, and then you will pay taxes on your gains. But you’re right. I read all these stories about, "I invested in Bitcoin and now I bought a car." Well, you’re not going to buy a car with the Bitcoin that you buy in your 401(k), unless you take it out, in which case you’d pay both tax and penalties on it if you were under 59½. So, certainly the money that you invest into Bitcoin in your 401(k) is not money that you want to get at any time soon.

David Muhlbaum: Yeah. We’re not the only people sounding caveats about this idea. The Department of Labor has gone all Debbie Downer on it too, so how do they fit in?

Sandy Block: Well, yeah, this week, the Department of Labor said they have grave concerns about what Fidelity has done.

David Muhlbaum: Grave concerns.

Sandy Block: Grave concerns. That should be a concern for employers, because private employers that offer 401(k) plans have a fiduciary responsibility to manage their plans in the best interest of their employees. The federal government department that is in charge of enforcing that fiduciary responsibility is the Department of Labor. So, if the Department of Labor isn't crazy about this idea, that’s not going to go unnoticed by companies that want to stay on the good side of the law.

David Muhlbaum: Right. So, the company has the legal responsibility, and the Department of Labor is looking over their shoulder making sure that they’re staying in the lines?

Sandy Block: Right, they’re the ones who administer ERISA, which is the law of the land governing pension plans, and 401(k) plans, and things like that. Basically it’s the law of the land that says if you’re a company with a 401(k) plan, you can’t cash it out and go on a cruise or something like that. So, it’s serious.

David Muhlbaum: All right Sandy, we will see how this one shakes out. Fidelity and the crypto community versus the Department of Labor. Coming up next, we will talk to Rivan Stinson about documents. Which ones to keep, which ones to shred, and which ones to keep near you in case of emergency. All coming up next on this episode of Your Money’s Worth.

Which Documents to Keep, Which to Shred and Which to Scan

David Muhlbaum: Welcome back to Your Money’s Worth. Joining us for today’s main segment is Rivan Stinson, a staff writer for Kiplinger’s Personal Finance. While she’s covered all sorts of topics for Kiplinger, when we last had her on Your Money’s Worth, it was to talk about insurance coverage for natural disasters. Today we’ve got disaster on the brain as well, because we want to talk about, in part, recovering from disaster, the paperwork part, that is. So, welcome Rivan. It’s nice to have someone to turn to for a disaster.

Rivan Stinson: I guess.

Sandy Block: You know, we could have Rivan talk about the cost of pet care. That’s been another one of her big topics.

Rivan Stinson: Yeah, my cat takes all my money, and he probably wants a sibling.

David Muhlbaum: Well, I think it would be great if we could have Nikon join in. Will he sign the release?

Rivan Stinson: Yeah, I’ll put his paw print on it.

David Muhlbaum: Cool, because nothing sells online quite like pictures of cats. But how about this for a topic then, Rivan? What to do with your pet when disaster strikes? Like when you have to evacuate, nobody wants to leave their pet.

Rivan Stinson: Well, no. One, let’s hope that they get in the carrier. Bring them some food, water, their meds. Thank God I don’t have a sickly cat. But my problem would be getting him in the carrier.

David Muhlbaum: Yeah, of course. Okay, what about something like a rabies certificate in case you were being evacuated and having to go live somewhere else?

Rivan Stinson: Well, I wouldn’t have thought about that. I would just hope the vet still has it.

David Muhlbaum: Right. In some places they give you an actual physical tag, like a little piece of metal. On my dog, it's on her collar. You see what I was doing there? I was getting us from pets back to documents, because that’s kind of at the core of what I want to talk about. You have an emergency of some sort, and to recover from that, you are going to need access to documents. So, the core of the question, and what you’ve been exploring, Rivan, is which documents do you have to physically have with you, which can you scan, and which can you not worry about? So, that’s what I want to get to.

Rivan Stinson: Okay. Well, the easiest answer was that you can scan everything. The issue comes moreso, when do you need an original document versus a scan or a copy? Usually that’s moreso going to deal with your birth certificate. States, and any type of government agency, just does not like a copy of your birth certificate, in terms of the scan. They want that original piece to say what hospital you were born in, who is your mother, who is your father, everything like that. For that, you want to store it somewhere that will not get destroyed. Nine times out of 10, that is going to be a safe deposit box, or if you have a fireproof safe. You need to get it out of the house, put it in a Ziploc bag so nothing floods. But in everything else, digitize it. You should keep your Social Security card with your birth certificate as well. But when was the last time you pulled out your Social Security card? I rarely do, I just write my number down.

David Muhlbaum: Rivan, for someone concerned about a natural disaster at their doorstep, they know they need a go bag, packed with what they and their family absolutely must take with them. But the idea of going to the file cabinet, and getting a packet of critical documents and cramming that in there, you’re saying that’s obsolete?

Rivan Stinson: Yes. Because nine times out of 10, you probably have everything on your computer, on your phone already.

David Muhlbaum: You should.

Rivan Stinson: Or you should. Because let me take that back, my father does not, but he does have a safety deposit box, and I know where the key is at. In those types of situations, you can also probably grab your license. That is the first thing.

Sandy Block: Your driver’s license?

Rivan Stinson: Your driver’s license. First line of defense, in terms of identifying who you are to do things. These other documents, let’s think insurance policies, maybe a healthcare directive, you have a copy somewhere in the internet ether, and that’s because it’s a login account.

But now with technology also comes other issues of just remembering your 50 million passwords to get into all of these places. For that, it’s more so where are your passwords? Again, if you are old school like my dad and writes all his things down, you keep that list of passwords and your safety deposit box. Or if you’re a little more tech savvy, you can share it with a trusted friend or family member. You need to have a backup to make sure you can log back into your accounts.

Sandy Block: For a lot of people, Rivan, this might sound like a lot of work. I know one of the things we’ve talked about is, for example, doing an inventory of everything you own for purposes of filing for insurance. But hasn’t technology made that a little easier now?

Rivan Stinson: Yes. It’s literally as simple as downloading an app on your smartphone, either yours or your kid’s. Or if you happen to have a newer printer, which I do, that has a scanner, and it’s Bluetooth, put them right in there and do it. It’s moreso taking the time out t actually do that. But if you can snap a picture on your phone, you can create an inventory. You can keep your documents.

David Muhlbaum: How about doing video?

Sandy Block: Oh yeah.

Rivan Stinson: Video is also important, particularly when it comes to your home, because it’s hard to really describe in words what your home things are worth. But a photo it’s easier to see and maybe it will jog your memory in terms of, "Oh yeah, that was my great-grandmother’s cabinet. It was made of 100-year-old oak," and whatever the appraisal would be for that. But writing that down, you may forget some of those details. It’s just easier. It’s another way to record, on top of keeping maybe a Google doc that is the home inventory connected to that video. The video is just the easiest thing for you to do.

Sandy Block: Rivan, something else that you’ve written about, that for some reason, always generates a lot of reader mail, is not only where to store your documents, but how long you need to keep them. That particularly comes up with respect to tax records. Since we’re not that far away from tax day, if you could run through what you can keep, and which ones you could actually safely shred at some point?

Rivan Stinson: Okay. In general you want to keep all your tax documents about a three- to four-year rolling basis, and that’s because the IRS has about three years to audit you. You want to make sure you have the documentation to claim all the deductions, if you itemize and things like that. However, things get a little more complicated if you have a broker account, maybe you have some IRA contributions. For the broker example, you want to keep those things for 10 years, only because if IRS thinks you’ve underreported, they have a longer time period to audit you. Same with some IRA contributions.

Rivan Stinson: But in general, if your life is pretty simple and you have a W2 form, you just want to keep them for about three, four years. It also gets a little complicated if you’re a homeowner. You want to keep all of your documents until the day you sell your home, plus three years. That’s because you are going to have to prove your cost basis for your house, or your primary residence.

Rivan Stinson: That gets into, what was a home upgrade, what was this? That is all for the CPA to figure out, what is your tax?

David Muhlbaum: Yeah, because the crux of that is this exclusion in the capital gains on the sale of a house.

Rivan Stinson: Correct.

David Muhlbaum: Now, those values are, what are they, $250 for single?

Rivan Stinson: $250,000 for single, $500,000 for a married couple. That is how much of a sale you can exclude-

David Muhlbaum: From a capital gains tax level, right.

Rivan Stinson: Yes.

David Muhlbaum: So, let’s run some numbers here. What’s bringing that capital gain exclusion to the fore is in part the run up in home prices. The $250,000 and $500,000 exclusion, that hasn’t changed, but home prices sure have, and have gone up. Rivan, you had in your piece, and you actually used a sample with dollar values. I want to walk through it because I think it’s a good example of how this actually works. What you said is, you had a scenario where, let say you and your spouse bought a house 20 years ago for $200,000. Today you sell it for $800,000. So, that’s a profit of $600,000.

Now, in theory, you would have $600,000 in capital gains and only $500,000 of exclusion, so you’d owe capital gains tax on that $100,000 dollars. But if you had done renovations, you had remodeled the kitchen, the bathroom, replaced the garage door, whatever, and those all totaled up to, and were using round numbers here, $100,000, then boom, even-Steven, no tax.

Rivan Stinson: Correct.

David Muhlbaum: But to do that you need those documents.

Rivan Stinson: Correct. Because things like home maintenance such as painting and your general repairs does not count for that. So, to say on the safe side, you might as well keep everything that’s big. It just makes the CPA’s job easier.

David Muhlbaum: But this could be literally that file folder full of like, "This is the tile samples, and here are the five punch list things." Right?

Rivan Stinson: Correct.

David Muhlbaum: Digitize.

Rivan Stinson: Yes.

David Muhlbaum: Don’t take it with you.

Rivan Stinson: This is the fancy faucet that I bought for my remodeled kitchen. You got to know that.

David Muhlbaum: Right.

Sandy Block: I think either scan, or just keep receipts for all of that work that you had done. Because you don’t want to be calling up your contractor on April 14th saying, "I need all these receipts for roofs and fences and upgrades."

David Muhlbaum: That is the most fictional thing I think I’ve ever heard. You’re going to reach a contractor from 20 years ago to give you details about the job that you both left in a huff. Yeah, that’s just not going to happen.

Rivan Stinson: Yeah. So, my suggestion there if you are really paranoid person, and this will be my mother, she did it both. She does have a box, plastic bin, that has all of her stuff in it. She told me where I can find it, because she did some replacements and all that. I think she’s also scanned it. So, you can do both. It’s more so if the original document gets destroyed, you have a backup to prove everything.

David Muhlbaum: Right. Well, the destruction, which was the theme of your most recent piece about financial emergency in the time of serious natural disasters, we talked about the safe deposit box being where to bring things. But we had situations with the fires in California, and Australia for that matter, where places with safe deposit boxes were burned. It’s unlikely, it’s improbable, but it’s kind of unnerving.

Rivan Stinson: It is. For that, I would ask the bank, how do they protect those safe deposit boxes? This is why it’s important to, at least if you can, grab your driver’s license or passport, because that will be your starting point to rebuild your life. Again, most of these things we’re doing now are on the web, or it’s a scan, you just need to log in.

Maybe you don’t need your birth certificate today, but you do need to get into your bank account. That would be more important. You just got to remember your bank account login. If you don’t remember that, now where are those passwords? Did you back the passwords up with either a friend or family? Do you use a password manager, such as LastPass, which does have an emergency feature to allow others into it if you can’t? Do you use something like a Google drive? Do you keep things in your Apple iCloud? Anything that can make this quicker for you to do.

Rivan Stinson: Even if your iPhone or Mac gets destroyed, as long as you remember your Apple ID and password, you can reset all that stuff. If you are prone to forgetting, I would suggest you share it with someone that is a trusted friend or family, because Apple does not have an emergency access feature.

David Muhlbaum: Yes, I know from personal experience that an Apple ID is a difficult thing to get a reset on, but there are others that are worse. As you mentioned, getting a duplicate birth certificate or a Social Security card, but not impossible.

Sandy Block: Not impossible, and I think that’s why you want to scan all this stuff. Because if worst case, the bank burns down with your safe deposit box and those documents in it, you can track them down. It’s going to take some time, but I have done this, you can get your birth certificate if you know where you were born. You can find these things, but having the originals digitized will speed up the amount of time it takes to track them down.

Rivan Stinson: Correct. If you don’t know what office to go to, I believe the article has where you should go. I think David will list that within this podcast link. But like Sandy said, you can replace your birth certificate. Replacing your Social Security card is easier now, too. Again, you log onto the Social Security Administration website.

Sandy Block: Yeah, I recently replaced my Social Security card. It can be done.

David Muhlbaum: In the end, what it comes down to is doing the work ahead of time. We think of disaster prep as things like ... Well, are the gutters cleaned is kind of basic. But if you live in a fire zone, creating a defensible area, making sure that your roof doesn’t have brush or needles on it. I’m revealing that I don’t live in a fire zone, but I know there are things you should do. But some of that prep work is just sitting down with the computer, with the phone, and doing the administrative work.

Rivan Stinson: Yes. Make it fun. I do all my administrative tasks with a glass of wine, it’s great. Yes, you just have to sit there, and you also have to tell people where they are. I will say I appreciate the fact that every time I come home, my dad tells me exactly where his safe deposit box key is. It’s a little unnerving to keep talking about his impending death, but at least I know where things are.

Sandy Block: Since we’ve been talking so much about safe deposit boxes, I think it’s important, because we got mail on this, to remind or advise people that you should not keep estate documents in there. The reason for that is if you die, and your relatives don’t have access your safe deposit key, they’re not going to be able get to this information that they need to settle your estate.

Sandy Block: Now, in Rivan’s case, her dad tells her where the key is. But unless you have the key, if your name isn’t on the safe deposit box, you can’t get these documents. It will be kept with your lawyer, or with your executor. You could digitize, but don’t leave the original copy of your important healthcare proxy, estate documents, in your safe deposit box, because you could be in a situation where people who need them cannot get them. We get a lot of mail on this, so I think it’s important to point out.

David Muhlbaum: I have a couple more details on the will thing. I believe, in some states at least, this was the case in Virginia, the lawyer was able to essentially file the document with the courthouse, so the document is sort of always there. It’s with a seal at the court.

Rivan Stinson: That’s right. That reminds me of something I learned through research. If you don’t know, ask your financial planner, if you have one. Ask your doctors when it comes to healthcare proxies. Ask people, "Do you have a system to store this in case something happens to me?" Particularly if you don’t have family close to you to get to that.

Sandy Block: One of the things Rivan noted in her story is that if you’re gone and no one has a safe deposit box key, the bank doesn’t keep a master. Someone has to hire a locksmith to bust into your box. It’s not like you can tell the bank, "I lost the key. Let me in." They won’t do that. It’s important that you have some kind of backup, some kind of system. Don’t assume that people can get at documents in your safe deposit box if you’re not around.

David Muhlbaum: Well, to go back to the disasters, that we’ve dragged Rivan into being our disaster professional, we’re recording at the start of what we historically have thought of as, well, disaster season, if you will. Wildfires, hurricanes, of course New Mexico’s already on fire. But I think it would be good, Rivan, if you gave us a reprise, partly from last year, but partly because it’s still an issue, homeowner’s insurance. What it does for you in disasters, and what it doesn’t, and how you fill those gaps?

Rivan Stinson: First off, talk to your insurance agent before disaster happens. If you live in an area that is prone to anything, you need to understand how it works. For example, say you live in Florida. High winds for a hurricane. If damage is done by the winds, that’s a separate deductible. Or if your house is flooded, that is not covered by your standard homeowner’s insurance policy. That is a different policy that you have to buy through to someone else. With a wildfire, nine times out of 10, the insurance will cover the cost of replacement. The issue is you can’t change coverage in the midst of disaster, whether it’s wildfire, floods, a known storm, tornado. You can’t call your insurance and be like, "Hi, I think I need to add some more coverage to my home." They’ll be like, "No, we can’t sell you any more."

Rivan Stinson: They will stop business and restart at a predetermined time. That can be a little bit after even the storm is passed, because they don’t want a spike in claims. You have to do that administrative in-house work months before, just to make sure you’re covered. Again, if you’re not sure if you have enough coverage, talk to your insurance agent. They should have tools to help you estimate things, in terms of if you keep expensive jewelry at your home, if you have expensive tech, considering all of us have been working from home the past two years. If you don’t know, ask.

David Muhlbaum: Mm-hmm.

Sandy Block: One other thing you mentioned in your story, Rivan, is that a lot of people may not have enough coverage because of inflation. Prices have gone up, and the aftermath of a disaster, a lot of times labor and other supplies will cost a lot more. People need to make sure that the coverage they have now is really going to make them whole if they lose their homes, correct?

Rivan Stinson: Correct. For that, you really want to ask about an extended replacement rider. This should help you cover the cost of inflation, and things like that. This is also, it comes back to, remember your home upgrades. If you upgraded your home, but haven’t upgraded your homeowner’s insurance, that is going to take the cost of building your home way up. You need to let them know what kind of materials. You also get discounts. If you put on a new roof, that’s an insurance discount, but they also need to know so that you can be properly insured.

David Muhlbaum: Well, it’s good advice. There’s an undertone here of, "Do the work, people." I’m sorry about that, but in the end, we’ll all be better off. Thanks so much for walking us through it, Rivan, appreciate it.

Rivan Stinson: No problem.

David Muhlbaum: That will just about do it for this episode of Your Money’s Worth. If you like what you heard, please sign up for more at Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your content. When you do, please give us a rating and a review. If you’ve already subscribed, thanks. Please go back and add a rating or review if you haven’t already. To see the links we’ve mentioned in our show, along with other great Kiplinger content on the topics we’ve discussed, go to kiplinger.com/podcast. The episodes, transcripts and links are all in there by date. If you’re still here because you want to give us a piece of your mind, you can stay connected with us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or by emailing us directly at podcast@kiplinger.com. Thanks for listening.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

In his former role as Senior Online Editor, David edited and wrote a wide range of content for Kiplinger.com. With more than 20 years of experience with Kiplinger, David worked on numerous Kiplinger publications, including The Kiplinger Letter and Kiplinger’s Personal Finance magazine. He co-hosted Your Money's Worth, Kiplinger's podcast and helped develop the Economic Forecasts feature.

-

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 and Nasdaq also had strong finishes to a volatile week, with beaten-down tech stocks outperforming.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

Is Crypto Investing Coming to a Credit Union Near You?

Is Crypto Investing Coming to a Credit Union Near You?Credit unions are getting in on crypto investing through partnerships with third-party platforms, but the risks to investors still apply.

-

How Parents Can Explain to Kids How NFTs Work

How Parents Can Explain to Kids How NFTs WorkNFTs and cryptocurrencies are part of the new digital world that’s here to stay, so parents and their children should learn the ins and outs.

-

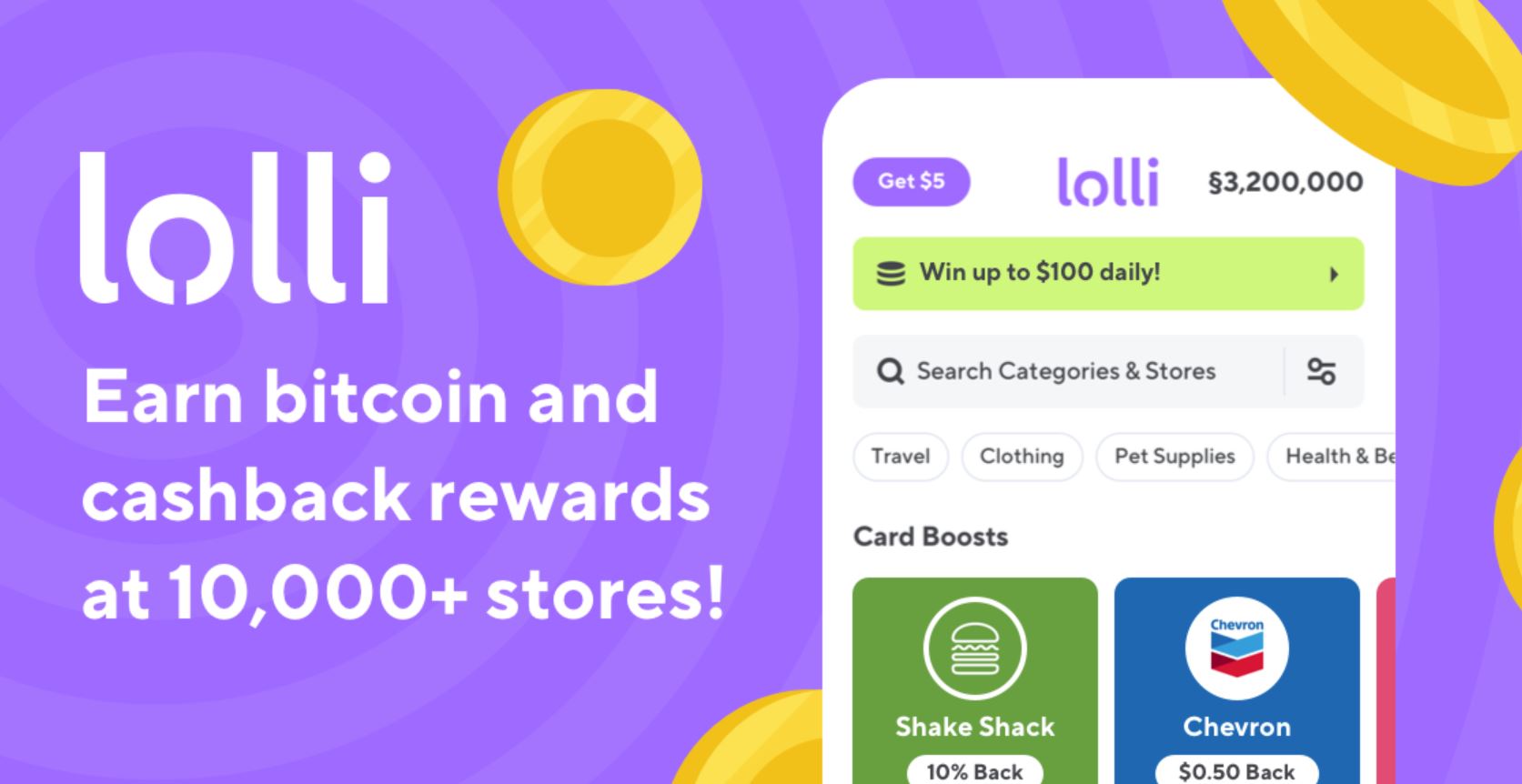

Earn Crypto While Shopping with Lolli, Others

Earn Crypto While Shopping with Lolli, OthersIf you’re crypto-curious rather than crypto-committed, a loyalty program or credit-card linked program can let you buy Bitcoin, other currencies a little at a time.

-

PODCAST: Tax Breaks for College Finance with Kalman Chany

PODCAST: Tax Breaks for College Finance with Kalman ChanyPaying for College Paying for (ever-pricier) college is a challenge that this consultant meets head on with highly specific guidance.

-

PODCAST: Car-Buying in an Inflated Market with Jenni Newman

PODCAST: Car-Buying in an Inflated Market with Jenni NewmanBuying & Leasing a Car With cars both scarce and expensive these days, what to do if you want – or need – a new ride? Car-buying strategist Jenni Newman of Cars.com shares some tips. Also, more on the magical 9% savings bond.

-

PODCAST: How to Find a Job After Graduation, with Beth Hendler-Grunt

PODCAST: How to Find a Job After Graduation, with Beth Hendler-GruntStarting Out: New Grads and Young Professionals Today’s successful job applicants need to know how to ace the virtual interview and be prepared to do good old-fashioned research and networking. Also, gas prices are high, but try a little global perspective.

-

PODCAST: Is a Recession Coming?

PODCAST: Is a Recession Coming?Smart Buying With a lot of recession talk out there, we might just talk ourselves into one. We take that risk with Jim Patterson of The Kiplinger Letter. Also, dollar stores: deal or no deal?

-

PODCAST: This Couple Tackles Love and Money as a Team

PODCAST: This Couple Tackles Love and Money as a TeamGetting Married Fyooz Financial, the husband and wife team of Dan and Natalie Slagle, have carved out a niche advising other couples with the money questions that come with pairing up. Also, where is this troubled stock market headed?